6.2 Experiencing Smell

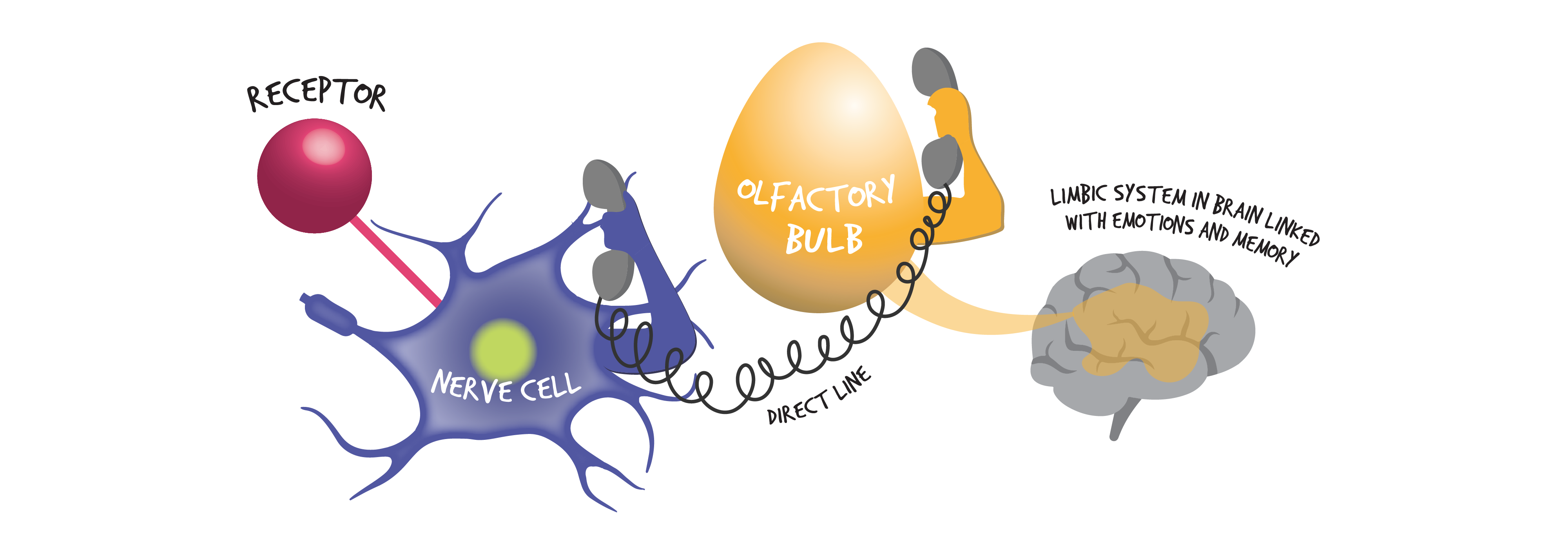

The experience of olfaction begins as a chemical process in which receptors in the cilia in your nose capture and send smell signals to your olfactory sensory neurons. These signals are interpreted as an electric impulse that travels to your brain (Derval, 2010; Cardello and Wise, 2009). You experience this when you inhale airborne smell particles (called odourants) during interactions with products or places; these odourants are translated into messages of pleasure (the smell of morning coffee) or danger (spoiled food).

The path of smell: from receptors capturing odourants to your brain interpreting them

In fact, your smell receptors can detect “at least one trillion different aromas, which makes smell a discriminating sense” (Jasper & Wagner, 2018, p. 50). The eye and the ear each provide much less information; the eye can distinguish among several million colours and the ear can sense less than half a million tones (Lipps, 2018).

You have many more smell receptors than other types of sensory receptors combined

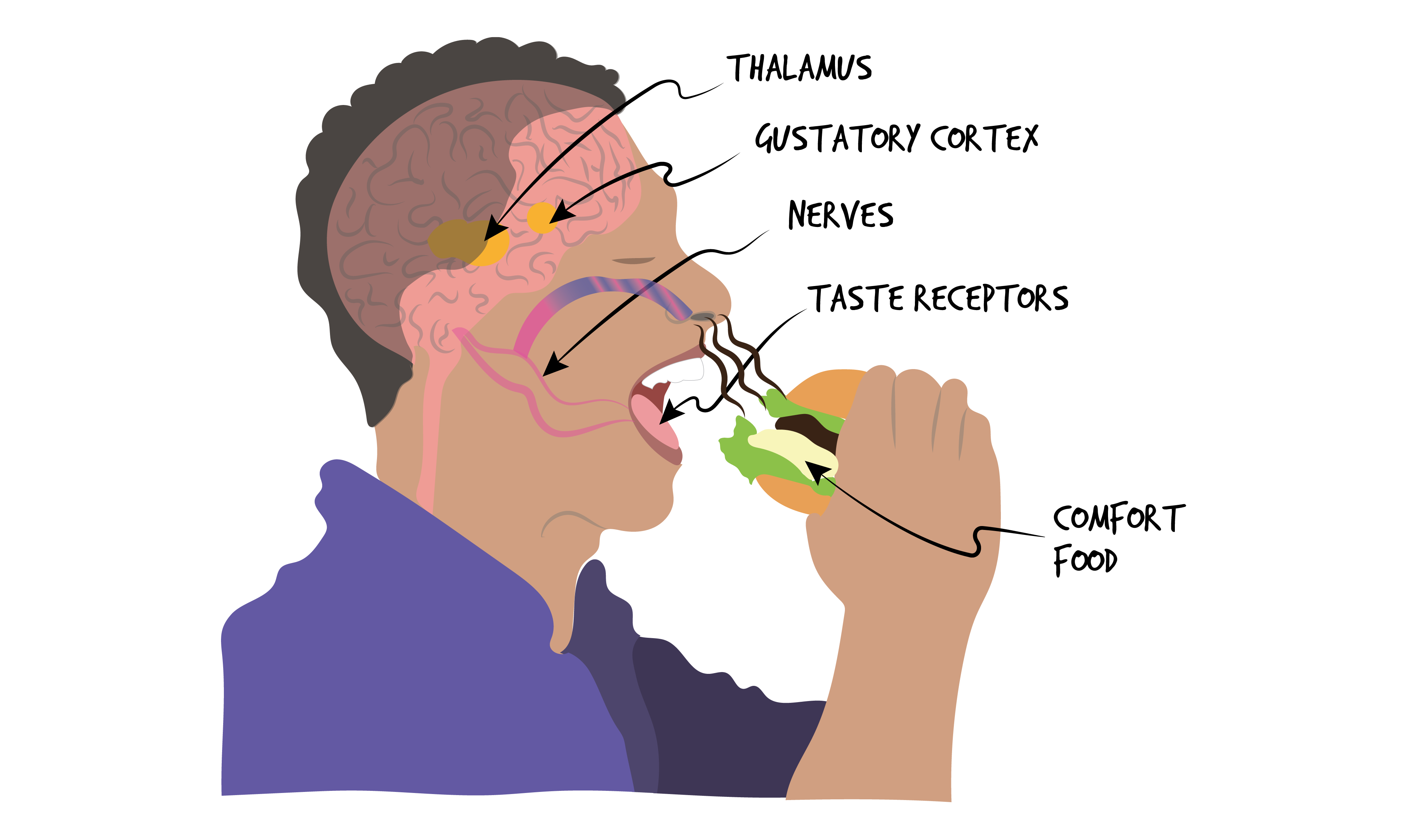

Think of the last time you ate a delicious meal. Do you remember what it smelled like? Do you remember what it tasted like? Can you separate the smell memory from the taste memory as you did with the earlier brownie example? Is your perception of one of those senses more memorable than the other? If you recall them as one overall perception, that is an example of how you perceive odours through two different pathways – the nose and the throat. When you sniff, smells enter through the front of your nose and that process is called orthonasal olfaction. When smells move into your nose from the back of the mouth while you are chewing or swallowing and breathing out that process is called retronasal olfaction and is related to your experience of taste (Auvray & Spence, 2008; Christodoulaki, E. 2016; Lipps, 2018). Your olfactory sense is thus considered a proximal (close) and dual sense because of its ability to sniff smelly molecules in the air and savour the scent of food. As well, smelling sometimes acts as a distal (distant) sense because it can also detect stimuli at a distance by means of their odours (Thavonekham, 2015).

Orthonasal Olfactory sensing when eating

Smell and Memory

Olfactory perception makes a substantial contribution to how people interpret their lived experiences through sensory links to smells, memories, emotions, things, and places. Smells have more power to immerse people in their surroundings through cultural and personal associations than any of the other senses.

Cultural Associations through taste and smell memories

According to the Auracell (a polymer scent product manufacturer) website (2020), “Research suggests that people remember 35% of what they smell, compared to just 5% of what they see, 2% of what they hear, and 1% of what they touch”. Even though scent is more connected to memory, people also look for additional information in the moment through sight, touch, and sound. The Auracell site also tells us that fragrances evoke moods and enhance brand recall. According to their site, that may be why the demand for fragrances that enhance products is growing. They argue that adding fragrance strengthens a customer’s perceptions of quality, leading to product brand loyalty. Are there certain products or places (e.g. soaps or coffee shops) that you prefer because of their fragrance?

Percent of what people remember from different sensory data

This experience is sometimes called the “Proustian phenomenon”, and supports the idea that there is a strong emotional connection between smell and memory. It refers to the involuntary childhood memory that overcomes one of Proust’s characters in Á la Recherche Du Temps Perdu when eating crumbs of a madeleine cake. In lay terms, it can be said that a signature smell evokes the emotional tone of the context in which it was originally experienced. This emotional smell can suddenly trigger specific memories from the past (Jones, V.E., 2017, p. 14).

Since you are now thinking about the power of your emotional attachments through scent, try to recall what happens when you smell coffee brewing. Do you experience attraction or aversion? What about the smell of welding? Or the smell of freshly cut wood or a newly mowed lawn? You may have originally experienced each of these smells while someone (maybe you) was using a product like a coffee maker, a welding iron, a hand saw, or a lawnmower; so your smell memories are connected to your product interactions. That means when encountering those products later, the smells may bring up old memories that you then attach to the new interactions.

Your smell memories can become associated with specific product interactions

The Taxonomy of Smells

It may not be easy, however, to describe your smell memories. Jasper and Wagner (2018) tell us that there is a lack of a specific smell vocabulary and many smell descriptions are borrowed from those of other senses, where we might say that something smells sour (like the taste of a sour fruit) or that it smells heavy (like the tactile weight of a material).

Expressions we use that describe the character of smells

Our individual odour preferences may be learned over time and may also be culturally dependent. Since we interpret smells differently, similar smells may trigger varied emotional responses, depending on the original context of the smell experience. That means designers need to conduct user research to understand how people respond to the fragrances they plan to use to avoid designing a product with a negatively perceived scent. Before a product goes to market, user studies can predict the likely outcome of product acceptance due to smell alone. For example, Lindstrom (2005) believes that a popping corn (and butter) smell is so closely associated with the experience of going to the cinema that the scent alone can attract moviegoers. He recounts a story of a Chicago cinema owner who installed vents on the street outside his theatre to pipe the popcorn smell onto the street prior to starting the show. He found “that magically evocative smell helped him fill seats in a matter of minutes” (Lindstrom, 2005, p. 18). This is like the allure of the smell of baking bread for a bakery.

The aroma of baking bread draws people into the bakery’s retail space

Not all of us appreciate the smells around us, perhaps for good historical reasons. Many cities have been characterized by their smells – of animal, human and industrial waste – in the urban environment, waterways, and industrial sectors. For example, the City of Peterborough, Ontario smells like oats from its Quaker Oats Factory and many small towns in Quebec had a smelly reputation until recently due to their pulp and paper mills. Sometimes pervasive and unpleasant odours need to be controlled. Odour management includes these three factors: separation, deodorization, and masking (Thompson et al, 2017). Separation involves isolating the smelly offender so that it can be contained. This occurs when you take out the smelly garbage. This is followed by a process of deodorization, often involving chemicals and air filtering devices that treat the source of the odours to neutralize or lessen their intensity. This occurs when you put an open box of baking soda in your fridge. Lastly, masking can be as simple as spraying air fresheners that provide a fragrant odour to distract visitors from unpleasant odours in the vicinity or as complex as applying harsh chemicals (Decottignies et al, 2007). Masking odorants usually mix the masker and the offending odour to reduce or cover up the unpleasant odour.

Garbage bags are often treated with a fragrant odourant to mask smells

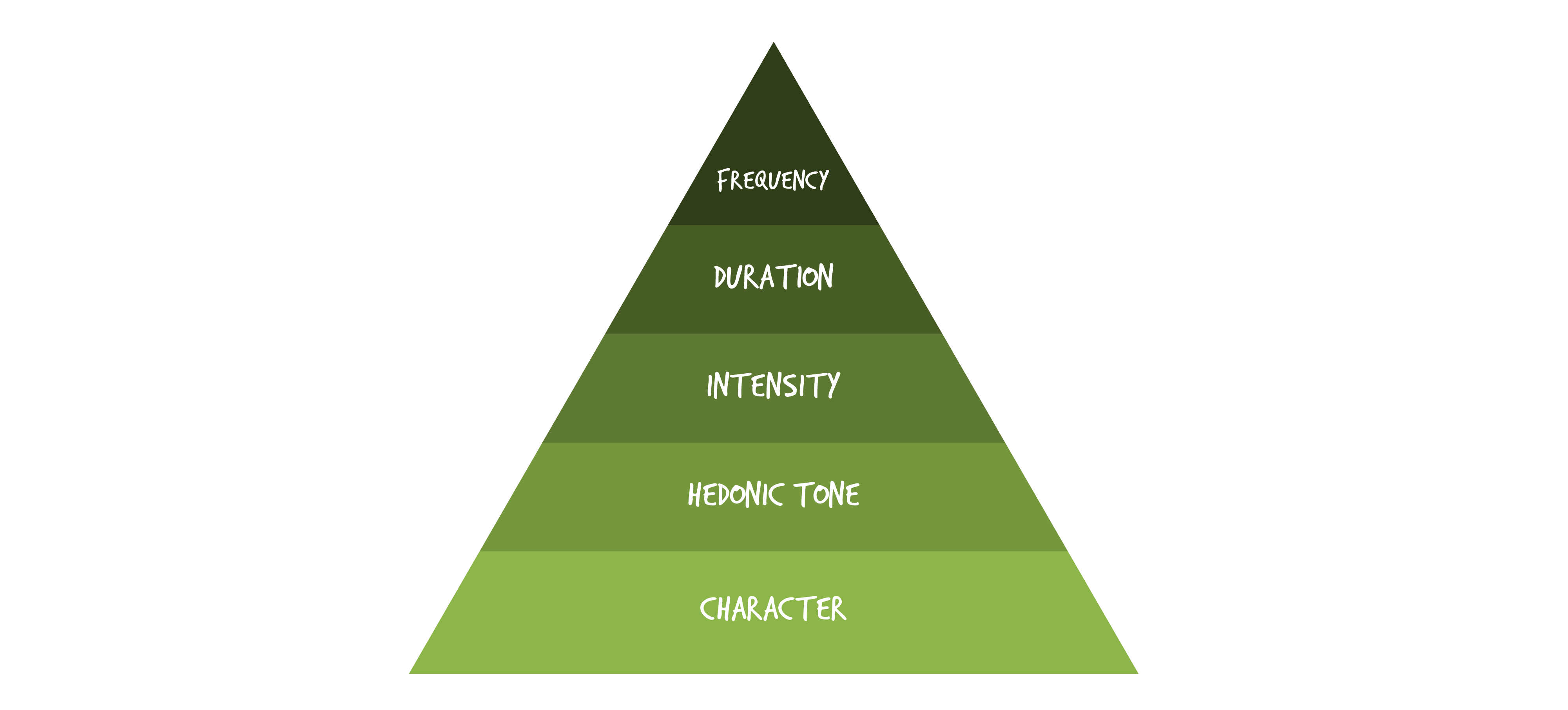

Urban planners and environmental scientists use criteria for measuring smells so that they can provide data that help professionals to minimize or eliminate odours from environments (Bull, M. 2017). In the air quality and waste management industry, the characteristics of an odour can be measured and defined, using terms similar to those for sound quality: odour character, hedonic tone, odour intensity, duration, and frequency (McGinley, P. E. 2000). These are described below and are terms that can be applied to designing smells:

Odour Character refers to how we describe the smell of an odour, as bad, stinky, terrible, or offensive. This description is objective and selected from a standard measurement scale of odour quality. These odours warn us to stay away from the source of the smell.

Hedonic Tone refers to subjective descriptions of the quality of an odour, usually based on our life experiences and feelings. In this case, the description might include emotionally loaded words like scary, threatening, or unpleasant. These odours are connected to our emotions.

Odour Intensity refers to how strong we perceive the odour to be, whether pleasant or unpleasant. Think about when you encountered someone with a very strong perfume or cologne; you may recall something about its intensity. Our reactions to these odours vary depending on how sensitive we are to smells.

Duration refers to how much time it takes for us to continue perceiving the smell of an odourant; this is the amount of time we experience a single odour episode. For example, you may enter an elevator that a caretaker with a garbage cart has just vacated and the smell that remains behind does not even last for your entire ride up. That odour episode had a short duration.

Frequency refers to how often you perceive odour episodes. You may consider changing your route to work if you experience getting on the elevator at the same time as the caretaker with that smelly garbage cart every morning. The daily frequency of that smell episode could be affecting your quality of life.

This odour inspection pyramid begins with character and as the issue becomes more significant it moves to the top of the pyramid (adapted from McGinley, 2000)

The pyramid above is a useful tool for odour enforcement in urban environments so that the appropriate professionals can neutralize offensive odour situations. However, taking a more positive spin, it may be adapted into a helpful tool for characterizing the qualities of scents that designers hope to imbue in products and product experiences, which is the reason that the term hedonic tone is important in this list. For example, in bathrooms and kitchens, scents are often added to mask emerging odours from natural activities such as composting and storing garbage. We want to have pleasant smells in our kitchens to enhance our experiences preparing and serving food.