4.6 Meanings Associated with Material Sensations

As you can see designers use materials to create sensory experiences that we interpret in meaningful ways. In this section, we acknowledge that some meanings related to materials are not only derived from touch, they are so closely aligned with the substance of materials that the discussion belongs here. Designers often consider using tactile responses to material sensations to evoke associations related to previous product interactions. Do you remember when boating paddles were only made of wood? We perceive wooden paddles as classic, warm, and comfortable to hold. We perceive plastic and metal paddles, which are now widely used, as less expensive and more durable than wooden ones, but less comfortable. Our perception of their value relates to the materials and care each kind of paddle requires. It is not that easy to separate sensory experiences from cognitive and emotional experiences. Some tactile sensations are translated into emotions and memories.

Materials associated with different memories of use may elicit positive responses

Tactile interactions contribute to the meanings that arise when we interact with products in certain contexts. Elvin Karana (2010) researched the meanings that people attach to the features of different materials. In one study, she analyzed the meanings people associate with waste baskets and lighters and discovered that participants associated different meanings with different materials and shapes. She found that metal products were perceived to be cozy, sexy, elegant, futuristic, and masculine, whereas plastic products were perceived to be toy-like.

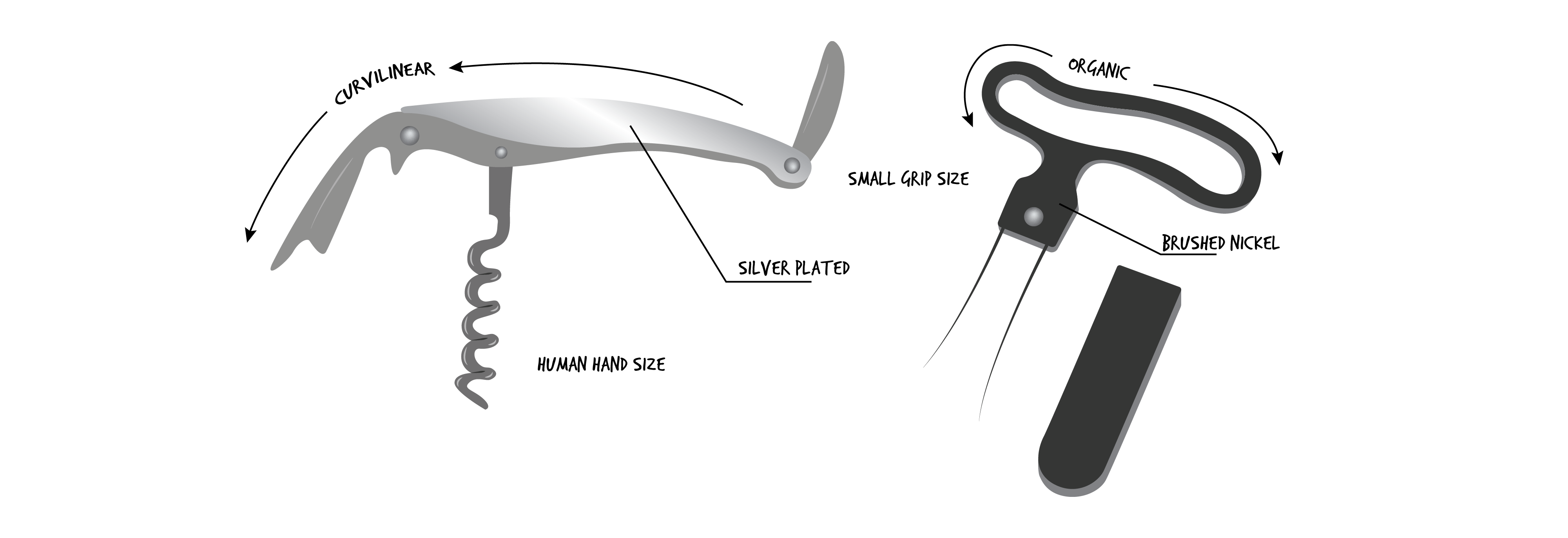

Meanings attached to materials: elegant (on left) versus toylike (on right)

Taking this concept further, you may see how materials can be interpreted as imparting a personality to a product, not only through tactile interactions but also through visual perception. A corkscrew made from metal feels cold and sharp. It may be perceived as having an aggressive and efficient personality, possibly a semantic association with a knife. Whereas a corkscrew made of plastic could be associated with the feeling of everyday tools and linked with utility and simplicity.

Different materials and tactile interactions can be associated with different meanings

Design researchers Ashby and Johnson (2003) also compared materials used for similar purposes to perceptions about their value. Their work shows that participants consider a plastic coffin to be cheap as it is more likely associated with a wastebasket and, therefore, inappropriate for its dignified purpose. You may have had wine in an exquisite glass and associated that with an upscale, elegant experience or you may have had coffee in a dinged-up metal camping mug and associated that with a cheap and rugged experience. Essentially, they are both drinking vessels made of different materials and, as a result, they provide completely different experiences that originated from completely different contexts.

Ashby and Johnson provide insights into meanings that link to our general perceptions of materials:

- Woods are perceived as warmer than other materials and are associated with traditions of craftsmanship. We also perceive it as ageing well and acquiring additional character over time.

- Metals seem cold, clean, and precise, especially when polished to reflection. Machined metal looks and feels strong.

- Polymers are perceived as cheap and easily scratched.

Different material perceptions

Ultimately designers cannot rely on their own material associations for determining the best materials for the product. It is critical to understand how others use or will use the products you are designing. What kind of actions will people perform with the product? How will they perceive it during their interactions with it? In a 20th-century redesign of Ingersoll Rand’s cyclone grinder (Peters, 1991, Frankel, 1994), designers observed that aircraft workers had built protective shields out of cardboard on their heavy metal grinders to protect their hands from sliding into the grinder while in operation. The workers also relied on their work gloves to insulate them from the heat of the grinder in action. Those observations inspired the industrial design team to develop concepts that incorporated lightweight and temperature-resistant polymers in the housing that could also be moulded into a “shield-like” formation that addressed workers’ tactile safety concerns. At the time, having designers study workers in action was considered innovative. Now we take it for granted that the more we learn about how people perform their typical product tasks, and how they perceive their experiences, the better we can design products that feel right for them and provide appropriate tactile sensations.