4.2 Tactile Aesthetics and Experiences

Our tactile experiences contribute to the feelings and meanings we attribute to the things we touch and interact with. Many of these experiences contribute to our perception of the tactile aesthetics of a product – our sensory responses to how a product feels, how we interact with it, or our sensory responses to our physical contact with objects. Professor Stuart Walker (1995) includes surface texture and tactile delineation to describe our aesthetic interpretations of objects. Our appreciation of a product’s tactile aesthetics arises in response to our experience of holding, using, and generally being in physical contact with the objects around us.

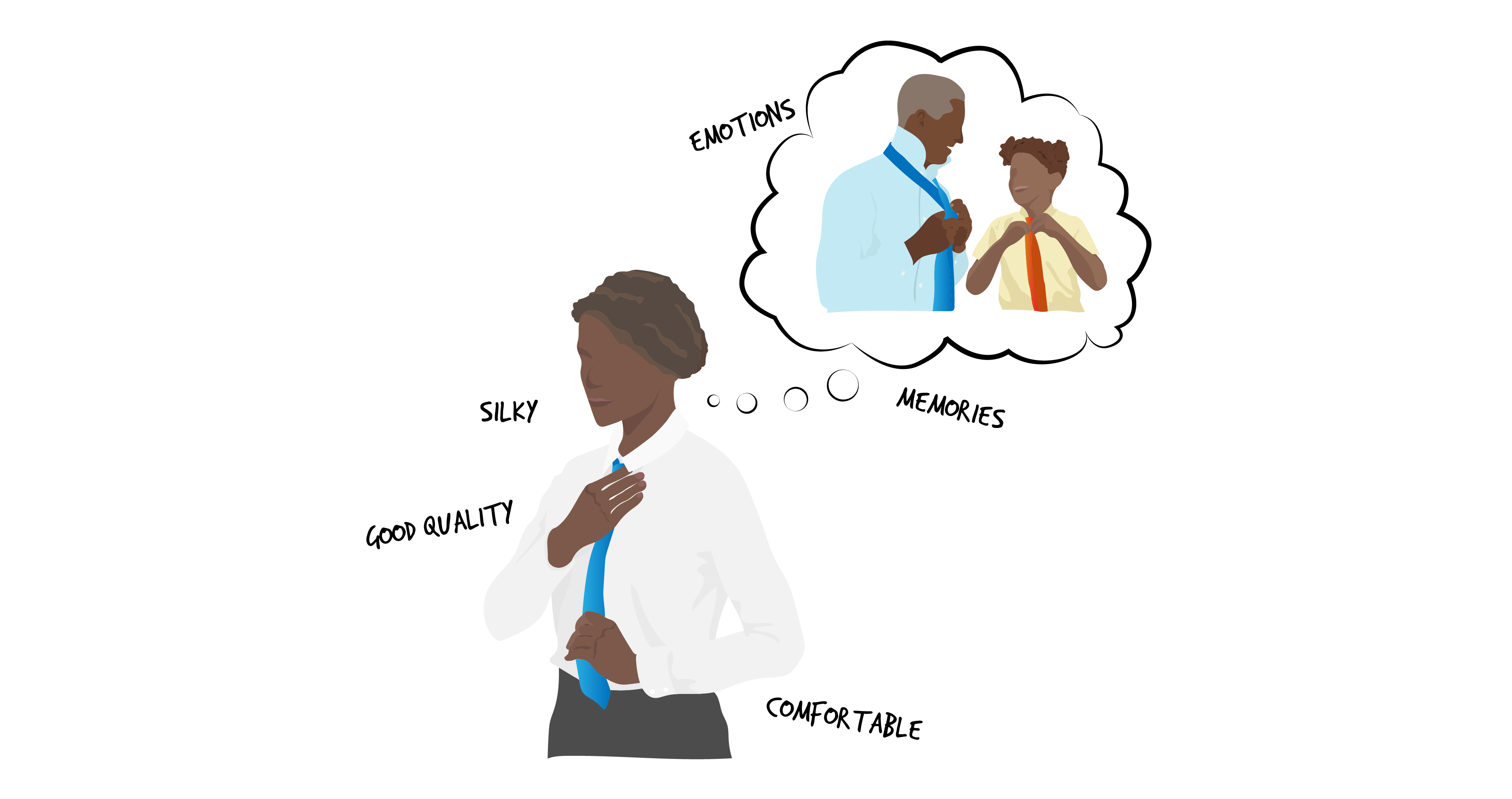

We experience a sense of pleasure or frustration through tactile interactions in three ways. First, when we use products as instruments, we get pleasure from our positive interactions to achieve our goals. Second, when we use the appropriate materials for product surfaces, we aspire to achieve our ideals at the non-instrumental level, contributing to our feelings of ideo-pleasure. This may involve making sustainable material choices, as we discuss later in this chapter. Lastly, we may gain pleasure from our emotional memories (socio-pleasure) of past tactile experiences with materials that contribute to our understanding of the material world around us. For example, the silky feel of tying a tie can bring back fond memories of the nuances of learning how to tie a tie.

Emotional meanings from past tactile experiences

We discover tangible information about a product through our sense of touch. Touching things also allows us to discern where the edges of our bodies are – where does my spine touch the back of the chair? How is the lumbar support from this chair better than that one? We already mentioned how some people can feel that an object they are holding somehow extends the limits of their bodies, whether by holding assistive devices to support balance or grasping a working tool to get a job done. Touch also provides information about materiality – something may look like glass, but as soon as we touch it, we can tell that it is made of glass or plastic because of the different thermal properties of those materials. Our ability to form impressions about what we touch depends on our finely tuned tactile sensations. Many of these tactile experiences are described in this chapter.

Products that are designed for people’s capabilities can improve their tactile experiences

Skin Sensations

We perceive touch through sensory receptors in our skin and muscles throughout our bodies. The sensory receptors in our fingertips and lips enable us to gather very detailed information about what we are touching. Mechanoreceptors send messages about pressure and vibration sensations. Thermoreceptors send messages about warm and cold sensations. Nociceptors send messages about pain. All of these receptors send tactile sensation messages to the brain, which interprets the intertwined sensations of pressure, resistance, and weight that contribute to our understanding of what we are touching. We even receive messages about how our body is moving during activities – that is kinesthetic information.

Mechanoreceptors in the fingertips gather tactile information

While most of us experience the feeling of touch all over our bodies, the quality of our perceptions varies in terms of sensitivity to detail, intensity, duration, and location of each tactile feeling. We experience different ways of touching; are we touching or being touched? All these sensations change over time or in relation to our health: older people and those with diseases like diabetes and multiple sclerosis experience decreased tactile sensitivity. From a sensory design perspective, good design depends on an awareness of the kind of tactile interactions a user could have with a product and designing features that would best facilitate those actions. We find two main types of touching play a part in demonstrating human-product interaction: active and passive (Sonneveld & Schifferstein, 2009).

Let’s begin with the concept of active touch, which refers to the activity of touching that we are most familiar with, although we may not call it that. We perform active touch all the time because we touch things, explore their physical properties, and get to know how they feel, work, and move. This tactile activity is also referred to as dynamic touch. We develop a tactile understanding of what each object is and does through actively touching it. Active touch refers to intentionally interacting with an object’s properties, mostly using our hands or other parts of the body, depending on the task. We actively experience a range of tactile interactions, from small to large, as we accomplish different tasks during the day. Think about what you are able to touch right now; are the sensations of touch similar or different when you switch between objects?

Many of these interactions are for instrumental purposes, where we are using the object like an instrument to achieve a specific purpose. According to Sonneveld and Schifferstein (2009), these kinds of activities include:

- Practical and functional uses like hammering a nail or entering information on a computer.

- Playful uses like swinging a tennis racket or golf club, rolling marbles, or online gaming.

- Carrying uses like wearing a backpack or purse, putting something in our pocket, or pulling a suitcase along.

- Personal care uses like brushing our hair, feeding a baby, mending clothing, or making the bed.

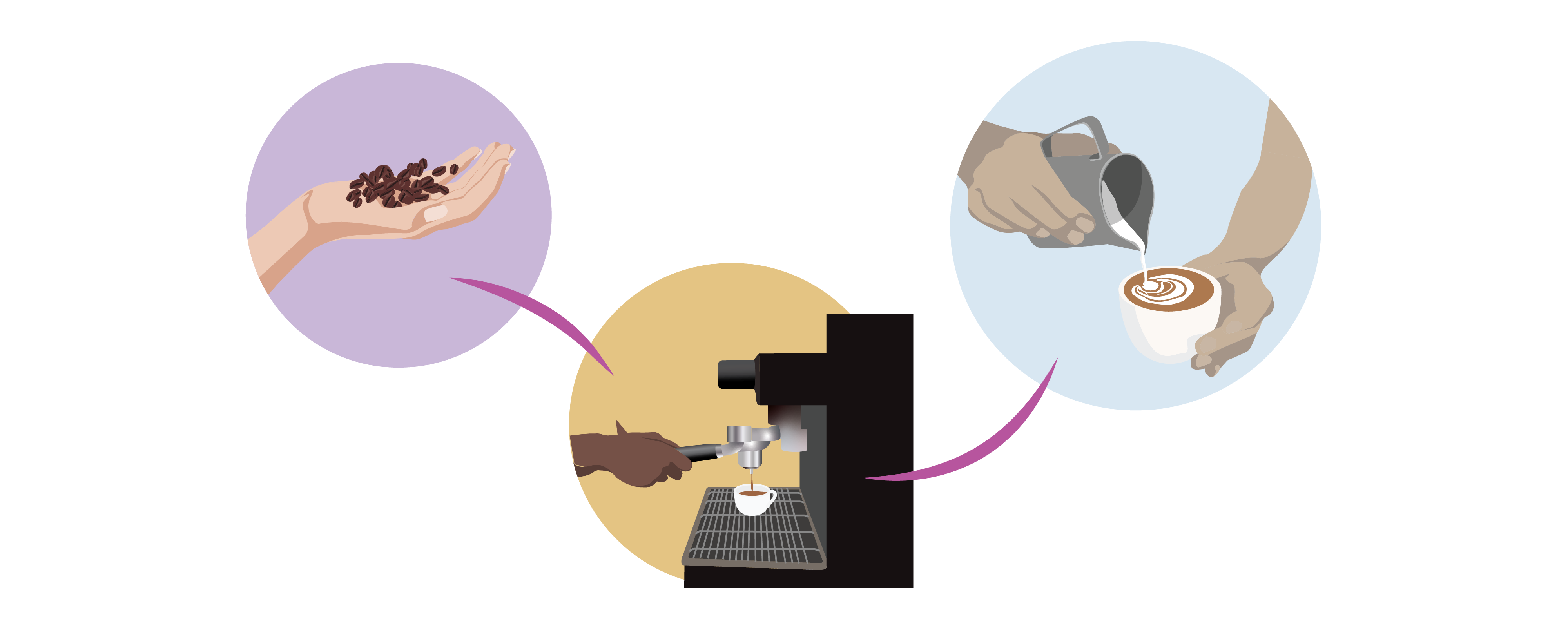

When a designer starts a new project, it helps to clarify the end-users’ goals and where they actively touch the objects that help them achieve those goals. Let’s say you are the designer tasked with redesigning a coffee machine. You may observe baristas working at different coffee shops, with their permission, to learn about their tactile interactions involved in:

- Grinding the coffee beans;

- Preparing the coffee;

- Adding the crema.

Active Touch: Tactile Interactions in espresso preparation

This kind of information is often so instinctual when someone has been doing the same job for a long time, that they may not be able to describe their interactions as clearly as when you observe the details yourself. Most of us process the tactile information we receive through our interactions with products, without consciously defining it. We learn how to interact with the things in our lives through hands-on experiences or active touch. In those cases we have what can be called tacit knowledge, knowledge that we just seem to know, but never describe. The beauty of design research is that it’s possible to observe people in order to recognize what does and does not work, which informs possible design improvements or innovations.

Some of our experiences involve passive touch, where the object touches us. We may not even consciously register that something is touching us, unless it is uncomfortable, itchy, painful, or feels downright unpleasant. When we sit on a chair, in a car, boat, or truck, the seat and backrest provide passive tactile sensations. Canadians love the feeling of heated car seats in winter – the seats passively warm us up. Passive touch also includes the haptic or tactile vibrations we feel when our mobile phone or smart watch sends a notification. My smart watch regularly vibrates to get my attention for various notifications. Someone made design decisions about the nature of those vibratory messages – the speed, the intensity, and the variations in vibration patterns. In the car industry, haptic or tactile feedback provides an additional mode of interaction for drivers, so they are not wholly dependent on their visual perception. Let’s look at the sensations involved in passive touch.

Sonneveld and Schifferstein (2009) note that the physical properties of objects can produce the following passive sensations of touch:

- A feeling of a light touch where no indentations or marks remain on your skin afterward; we all experience light touch when wearing clothing. Our awareness of this kind of touch dulls quickly because the sensors that detect light touch adapt rapidly.

- A feeling of pressure where indentations or marks remain on our skin afterward; the pressure is enough to feel deep and heavy sensations like when wearing a bathing cap for swimming. Our awareness of this kind of touch is maintained throughout the contact because pressure sensors adapt slowly.

- A feeling of vibration where rhythmic stimulation triggers rapidly adapting touch (high and low-frequency sensors). This occurs during a bouncy experience while riding in a motorboat over choppy waves or walking with a stone in our shoe. It also occurs when our smart phone vibrates in our pocket.

- A feeling of cold or warmth when touching anything with a temperature below 20 degrees Celsius (68 degrees Fahrenheit) or above 40 degrees Celsius (104 degrees Fahrenheit) like accidentally being touched by a hot iron or a cold icicle. Sensors rapidly adapt to mid-range temperatures, but not at these extremes.

Passive touch: The light touch of clothing or feeling stimulation from a stone in your shoe

The key thing to remember about passive touch is that design solutions may not be as simple as a good grip or a smooth surface texture. Designers may need to consider the whole environment or context in which an activity takes place. One example of how design can mediate passive tactile interactions is the use of shock absorbers in cars and bicycles to minimize vibrations from the uneven surfaces of the road or path.

Tactile experiences may also be intra-active tactile sensations, a combination of active and passive touch while doing an activity. For example, when using a hair straightener, as in the image below, we are actively moving one object over another static object, usually a part of your body – this is an intra-active tactile experience. You regularly have intra-active tactile experiences, for example when you put on a jacket or a hat, or brush your teeth.

Intra-active touch: the dynamic movement of the hair straightener actively moves over passive hair

Intra-active touch can also be perceived as different tactile sensations when interacting with the same product, as in the image below.

Intra-active (passive and active) touch can both be part of different tactile sensations in the same product

Pain and pleasure, as well as tickle and itch (mild stimulation across the skin when something is irritating), are also intra-active skin sensations responding to active and passive touch. Pain can occur at different levels, ranging from superficial (at your skin), to deep (in your muscles, bones & joints), and somatic (in your body). Imagine using a pair of scissors that painfully squeezed your fingers every time you cut something – this is an example of active touch when initiating the cutting motion, and passive touch when the scissor handles press against the fingers inside of them. Would you want to keep them? If a product is painful to use, it is unlikely that you will want to keep it, but if it is comfortable in your hand and works well you may enjoy its use for a long time. Perhaps you have experienced the fun of using a head massager like the one pictured below. This tactile activity is an intra-active tactile sensation that is pleasurable; it is a tactile physio-pleasure.

Enjoying the Physio-pleasure of a tactile tickle!

These tactile skin sensations enable us to understand and articulate how we experience the tactile properties of objects. They provide a context of tactile awareness for designers to work with to intentionally provide useful, comfortable, and appropriate tactile product experiences.