2.2 Form Factors of Compositions

Overall Perception

A composition is a structure, arrangement, or organization of design elements into a perceived whole. Compositions can be two-dimensional, such as an artist’s painting or a poster, where we convert the visual elements into a meaningful story to help us interpret what we see. Compositions can also be three-dimensional and, similarly, the sub-elements are arranged so that we can easily perceive them as part of a coherent object. For example, the housing or outer surface of your hairdryer is made of several elements. When considered as a whole object, it may look a bit like a gun with a handle in one place and a blower in another. When you think of a hairdryer, do you think of it as an object with a handle unit, a cylinder containing the mechanical components, with an air intake unit and an air output unit? Or would it be just a hairdryer with all these sub-elements harmonized into an overall composition?

The essence of developing a form that communicates information-rich messages is to determine the overall formal composition of the product. It may have many elements or parts, but nevertheless, there is often an overriding formal organization. Formal organization is a design term that refers to how the sub-elements in a composition are arranged so that they are perceived as one overall composition. Many designers sketch several formal compositions, with sub-elements that have different sizes, forms, and features that address the goals or requirements for a future product. We refer to this early stage in product design as the iterative stage because we are designing iterations or possible solutions to the criteria within the design brief; the document that specifies the product requirements. The requirements may specify function, target market, maintenance, and cost factors.

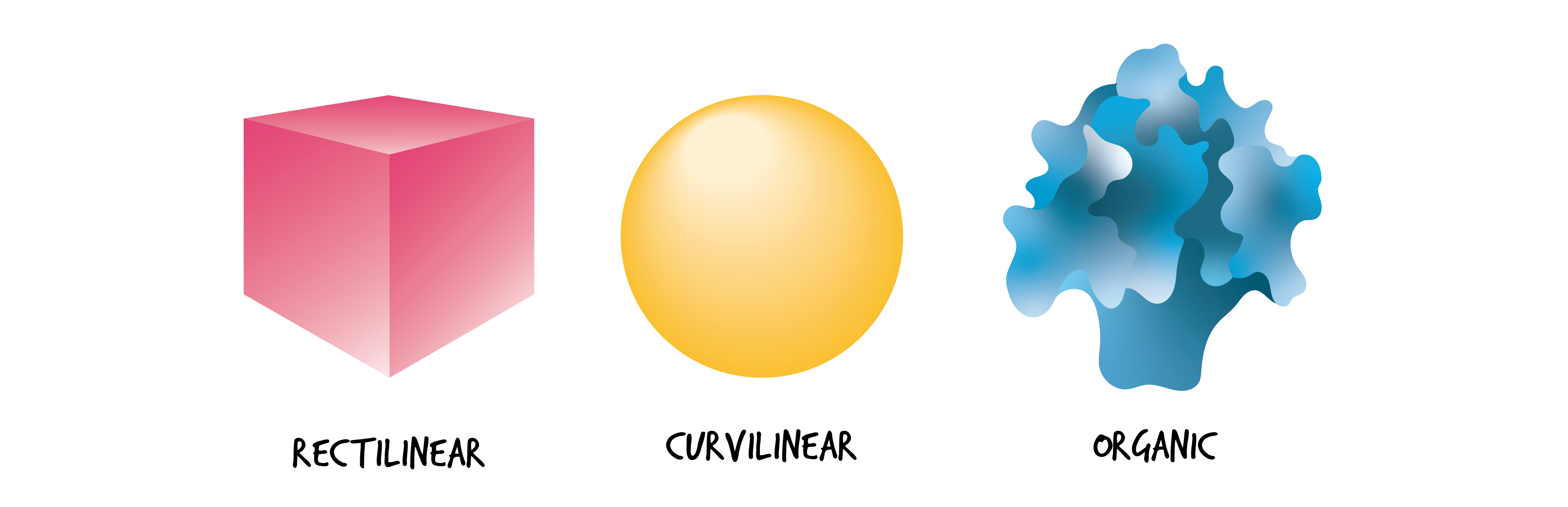

In the early stages of a design project, designers explore different arrangements of sub-elements, by integrating their forms, or form factors, into a whole composition. For example, you are tasked with designing a new type of bicycle pump that, when displayed for sale in a store, must stand out from its competitors. Form factors communicate messages that range from ease of understanding how to use the product and where it belongs to how attractive it looks; the cool factor often matters. The overall physical geometry of the form, which we call the typology, refers to the shape that people initially perceive – is it rectangular, round, or organic? These categories for classifying the formal properties of a composition are referred to as: rectilinear, curvilinear, and organic. Some compositions may be complex and have a mix of typologies. We discuss each separately in this chapter.

Formal Typologies

Rectilinear Compositions

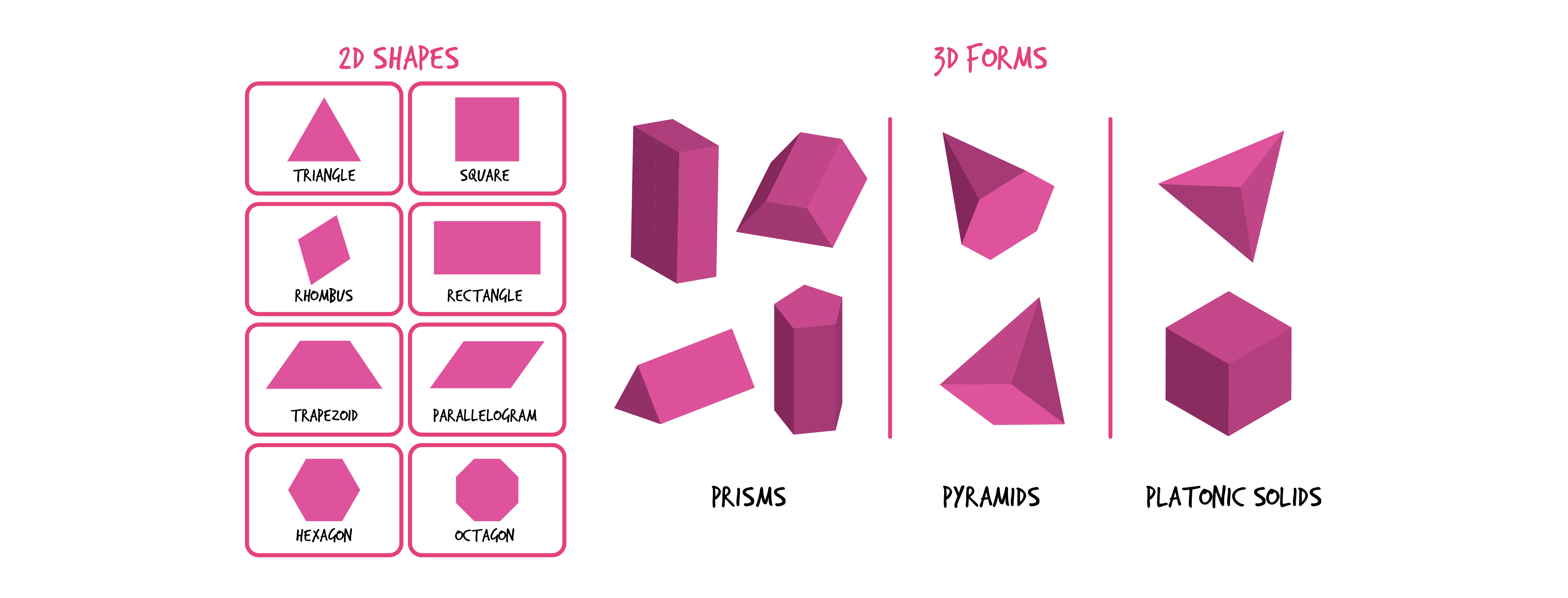

Rectilinear shapes or forms can be identified by their borders, which have straight lines, parallel or straight edges, and measurable angles. We call geometric rectilinear two-dimensional shapes squares, rectangles, triangles, pentagons, hexagons, octagons, etc. We call rectilinear geometric three-dimensional forms platonic solids (cubes, tetrahedrons, etc.), prisms (triangular prisms, hexagonal prisms, etc.), and/or pyramids (square base pyramids, triangular base pyramids, etc.). Human-made or manufactured products often have rectilinear shapes and forms with a sharp, clean, and angular appearance. Our overall perception of these compositions is that they are rectilinear. The rectilinear shape corresponds to the shape of the boxes that the products are tightly fitted and shipped in. Can you think of any of the products in your house that are rectilinear?

Rectilinear Geometric Shapes & Platonic Solids

Curvilinear Compositions

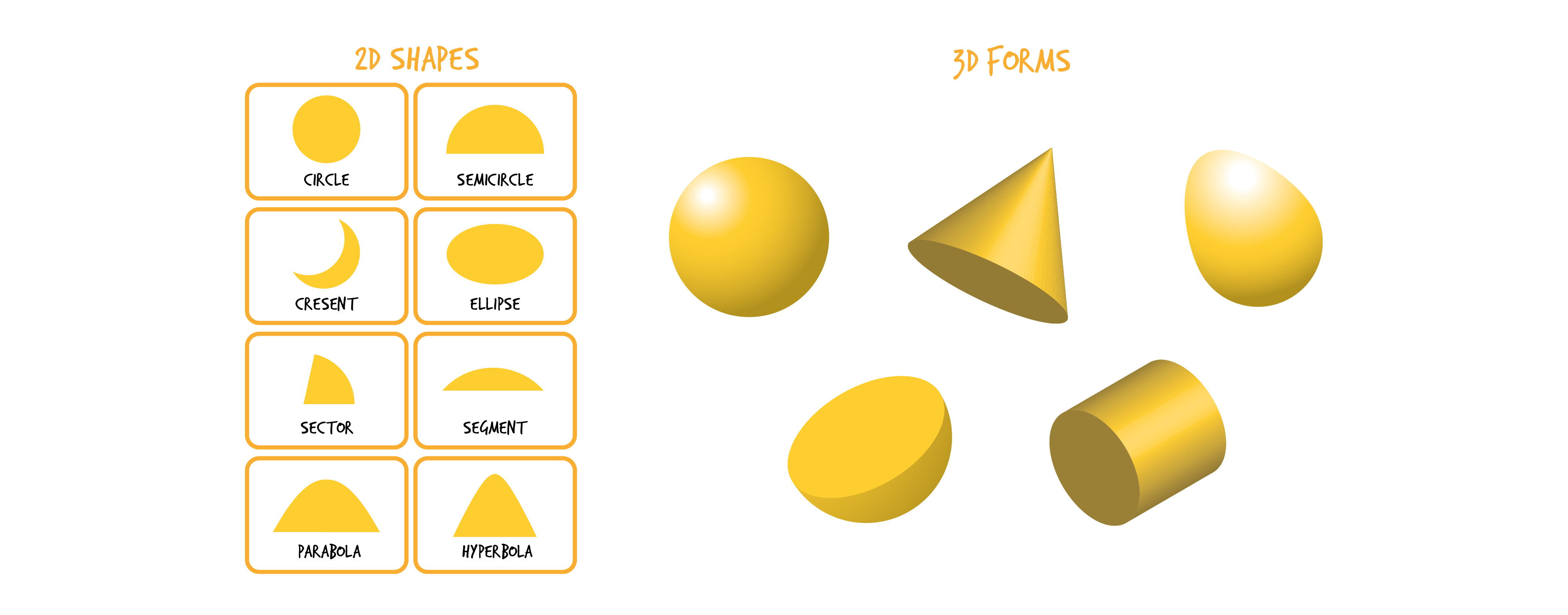

When we consider curvilinear shapes or forms, their boundaries usually have a curving line or edge. In curvilinear compositions, we find two-dimensional elements such as circles, crescents, ovals, ellipses, and three-dimensional volumes such as spheres, hemispheres, cones, and cylinders. Given the curving nature of the surface of curvilinear forms, we can perceive the composition by looking all around the three-hundred and sixty degrees of the surface. Curvilinear compositions can be simple, like a beach ball or ice cream cone, or more complex, like a seashell, trombone, or submarine.

Curvilinear Shapes & Forms

Organic Compositions

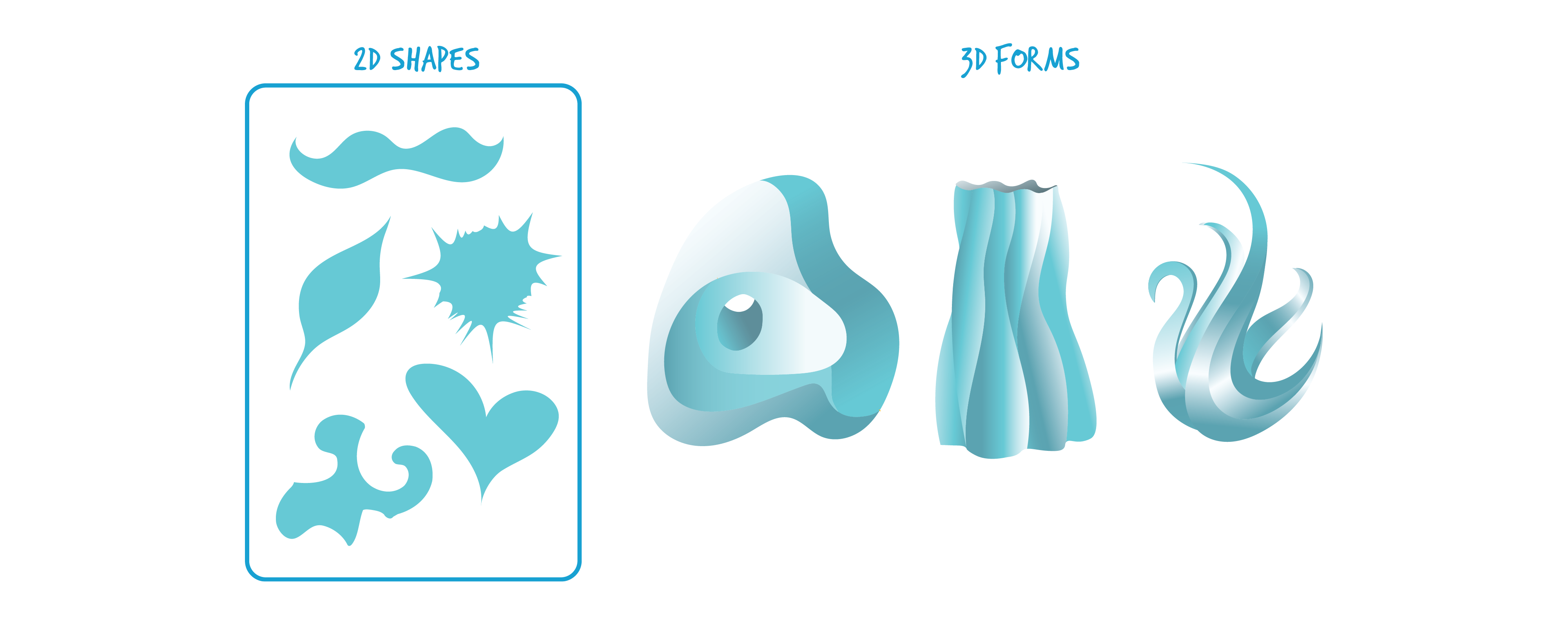

The third formal typology includes organic shapes and forms that often have irregular curving borders and may remind us of shapes found in nature. We may, at first, think of them as curvilinear, but they are usually irregular and often asymmetrical. For example, organic forms can be found in the design of bottles, light fixtures, and high-end household items, like bathtubs. They are sometimes referred to as biomorphic shapes or biologically-influenced design. These are generally inspired by natural shapes such as vines, leaves, water, and clouds, and can even reference animal forms. A good example of an organic composition is a propeller for a boat, helicopter, or airplane. What are the design elements of a propeller that could be derived from a maple tree?

Organic Shapes & Forms

Variations and Combinations of Formal Typologies

Everyday products rarely have only one formal typology or one type of form, usually they are composed of variations and combinations of design elements. Our perceptions of the overall form factors of objects as being rectilinear, curvilinear, or organic are supported by the way the composition is designed. We approach design by systematically organizing elements within the composition. In the early stages of concept development, designers develop a series of concept development iterations by mixing and matching typologies. There could be multiple ways to organize sub-elements to enable users to perceive them as a fully integrated formal composition. Our goal is to achieve an overall perception of a balanced composition that may also be perceived as having an overall typological form factor.

Variations and Combinations of Formal Typologies in Iterative Concept Development