1.8 Semantic Meanings of Products

Krippendorf and Butter (1984) introduce us to four semantic functions of products: expressing, describing, triggering (which Krippendorf calls exhorting), and identifying. These semantic functions provide more insight into ways to interpret the meaning and attributes of one thing (the signifier) and apply them to communicate the meaning and attributes of another (the signified). Let’s look more closely at them:

Expressing

A product’s overall aesthetic can include features that express the values, qualities, and properties of the product. Product semantic elements may convey stability, softness, heaviness, or lightness. For example, the power bank below uses design clues that incorporate form factors from rugged tires and an orange and black colour palette that signifies that it is a working tool resistant to all sorts of factors from shocks, vibration, dust, or solar radiation to extreme temperatures, low pressure, rain, fog, and humidity.

THE SEMANTICS OF THIS POWER BANK EXPRESS RUGGED USE

Another example of expressive product semantic elements can be found in this lightbulb, designed to imitate the form of a diamond, with sharp faceted edges that communicate extreme durability, clarity, and long-lasting use by symbolic association with a diamond.

THIS LIGHTBULB DESIGN EXPRESSES A DIAMOND METAPHOR

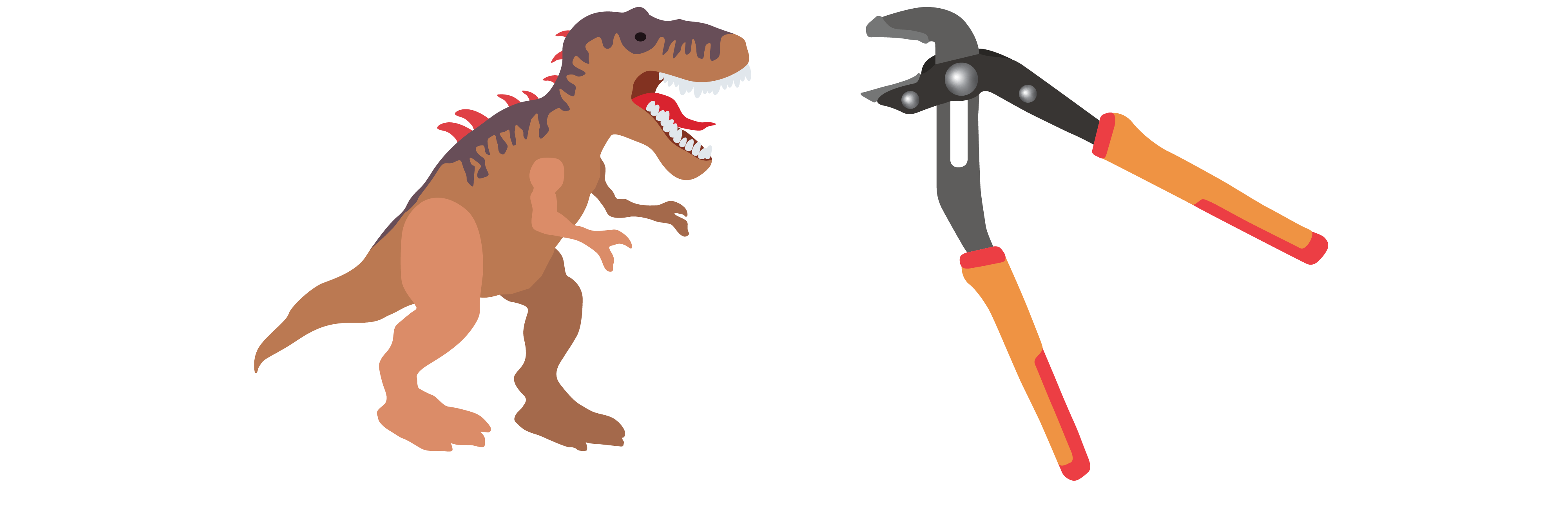

In the next example, the meaning and attributes of one thing could be compared to the meaning and attributes of another. Imagine that you start to make your own semantic associations for certain products – can you relate the overall form and stance of the pliers below to a tenacious and strong T-Rex dinosaur? Sometimes we perceive metaphors that designers did not initially intend, hence as designers, it is good to find out how users perceive the metaphors we embed into products.

THESE PLIERS EXPRESS A DINOSAUR JAW METAPHOR

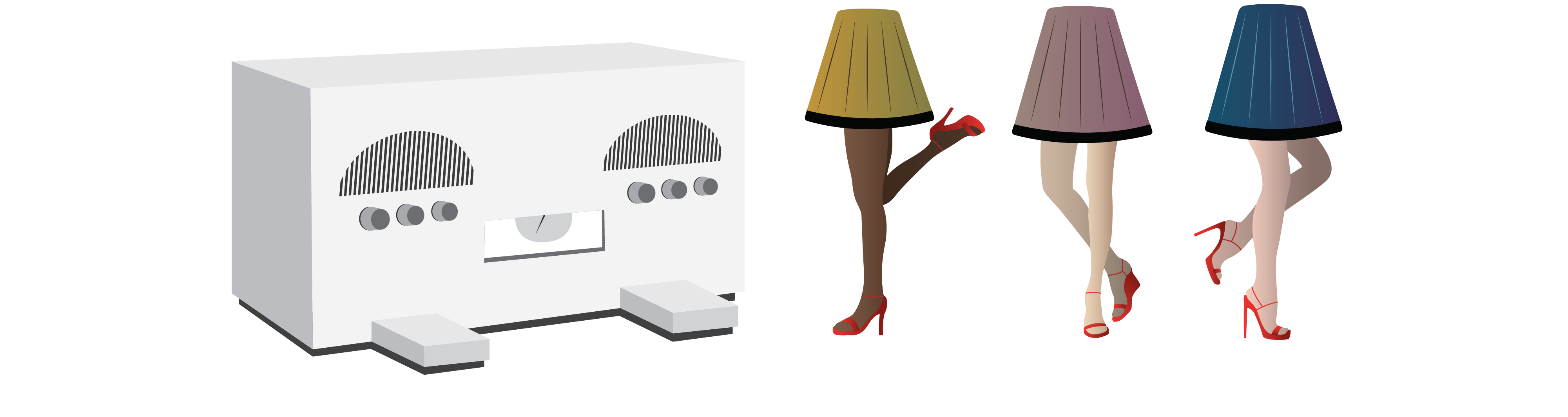

An important aspect of expressing semantic meanings relates to anthropomorphizing a product’s design features to inspire users to view the product as human-like. Anthropomorphizing refers to attributing human traits, emotions, or intentions to non-human entities. It embeds simple or sophisticated elements and traits into a product’s appearance that inspire users to behave as if the artefact has human qualities. These anthropomorphic elements can be intentionally designed or user-attributed (like naming a car) and may result in our becoming more attached to a product. In the images below, we can see examples of products that are intentionally designed to imitate human-like features.

2 KINDS OF PRODUCTS WITH ANTHROPOMORPHIC FEATURES

SOME PRODUCTS SIGNIFY ANIMAL ATTRIBUTES TOO

Describing

Product semantic elements can be used to describe the purpose and function of a product. For instance, a round door knob provides a descriptive clue for the user to grasp it whereas a door knob with a handle provides a descriptive clue for the user to push it down. The metaphor of a traffic light – green, amber, and red – is applied to the mobile payment device below. We may associate ingrained cultural and societal cues to direct, identify or link elements in an object. The machine incorporates the universal green for go, yellow to yield, and red to stop, which is a familiar societal reference. In this case, the signifiers are the three coloured machine feedback buttons that signify the same message as a stop light (go, prepare to stop, stop).

THIS PAYMENT DEVICE USES A STOPLIGHT METAPHOR TO DESCRIBE POSSIBLE ACTIONS

Triggering

The design of a product may play on product semantic messages that trigger a visceral response for the user – for example, to be careful or to be precise. Triggering clues can also be very specific in providing you with a message about how to operate a product. For example, if you grasp a hairdryer on the handle close to where the buttons are located, you will avoid covering the air intake and causing overheating. In this case, the cues that instinctively direct you to hold the handle implicitly direct you to avoid the danger zone at the air intake end!

SOME CLUES TRIGGER APPROPRIATE ACTIONS: THE HANDLE INVITES HOLDING

Identifying

A product’s semantic message identifies key attributes about it and in certain cases also about the human being who owns it. We often extend product attributes to product owners, which help locate people in the complex societal map of roles, groups, subcultures, age, and gender. For example, you may identify the owner of an iPhone as being cool and affluent whereas you identify the owner of an Android as being practical and less current. In addition to product semantic messages contributing to our human identity, iconic symbols of products can be associated with specific references, areas, cultures, or eras.

Social status can also be identified through product semantic messages, which address the commercial trend to own designer goods. Many people go out of their way to own designer luggage, which in the example below communicates a message of wealth, luxury, and elevated status.

SEMANTIC MESSAGES IDENTIFY LUXURY PRODUCTS & SEND STATUS MESSAGES

Owning a particular type of motorcycle, for example, may associate you with a specific subculture or age group. Owning a cruiser bike, a street bike, or a touring bike might also offer clues to the age or status of the cyclist. Sporting goods products depend on qualities like form, material, and colour to target specific gender and age groups.

BICYCLE SEMANTICS DIFFER ACCORDING TO THE CATEGORY OF CYCLISTS

MOTORCYCLE SEMANTICS TARGET DIFFERENT SUBCULTURES

Ideo- and socio-pleasures can also be related to branding decisions. In Yoon et al’s (2014) study of the Nuances of Emotion in Product Development, designers and marketers expressed an interest in aligning the impact of a product with the positive emotions that best represent its brand. For example, the Nike swoosh logo and the iconic Coca-Cola curves are considered cultural icons associated with leisure and recreation and are recognized worldwide. Can you bring them to mind as you read this?

Many well-designed products or objects contain encoded messages that communicate a purpose or meaning, both for the designer and the user. We are all exposed to product semantic messaging in our everyday product interactions. Have a look at the product semantic messages encoded into the razors depicted below: What population demographic do you think is being targeted for each one?

TRADITIONAL “GENDERED” DESIGN

These products are not gender neutral; design theorists call them gendered products because they are designed with cultural codes embedded into their features. Gendered products assume the target market for a product. As seen in the examples above, designers often associate a product’s design features with cultural codes through colours, forms, shapes, and materials connected with stereotypes. Some of these codes are associated with gender roles. Marketers and designers use these cultural codes to create and tailor products to be interpreted as suitable for specific genders.

Gender branding of products is not a modern concept; it is a centuries-old practice (Forty, 1986). However, it is a growing topic of interest among designers as we become increasingly aware of the impacts of product semantic messaging such as those above. Designers have taken an active role in perpetuating the gender-branding of products through the product semantics of form and colour. In this current time of gender questioning, is it necessary to design and create a variety of subtle and overt gender-branded products that only increase product waste in landfill sites? Perhaps the solution is not to design gender and culturally-neutral products, but rather, the designer is informed about who is using the products and how they are used, and avoids embedding products with semantic interpretations based on our own cultural assumptions (Powers, 2017). Understanding the kinds of use-behaviours people have with products, instead of relying on a bias toward design that supports specific gender identification, can strongly influence a designer’s choice of semantic or aesthetic features.

Many of these design semantic approaches are suitable for enhancing daily rituals and routines.