3.4 Volume Control Ventilation

Volume Control

In volume control, the clinician who is setting the ventilator will dial in the set volume for each breath. The control variable, in this case is volume and this is the primary variable measured and adjusted during inspiration.

We have learned how to find a safe range for tidal volumes for our patients, but what number do you start with? It is safe to start with any number within the [latex]6\text{ - }8\text{ mL/Kg}[/latex] range, for patients without ARDS.

|

Setting |

Steps |

Initial Setting |

|---|---|---|

| [latex]V_T[/latex] | Calculate Ideal Body Weight (IBW) and multiply with [latex]6\text{ - }8\text{ mL/Kg}[/latex] to get your safe range of tidal volumes | [latex]6\text{ - }8\text{ mL/Kg}[/latex] |

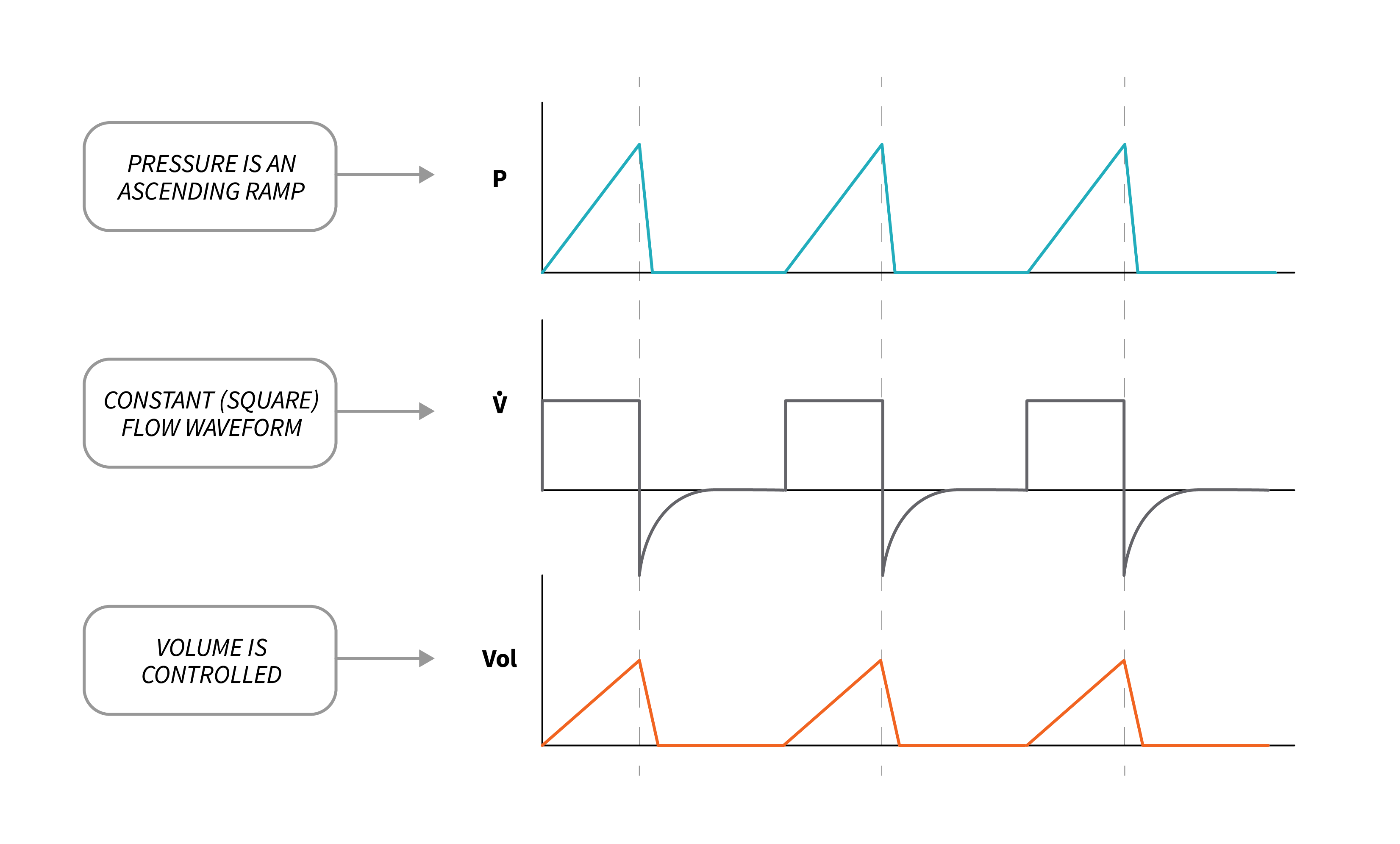

In Volume Control, we also usually set the max flow of air going into the lungs. Some ventilators will ask for you to set an Inspiratory time instead (discussed below) of a flow, but the classic versions of volume control have a max inspiratory flow setting. Often the default value for an adult patient, is usually a flow of [latex]65[/latex] liters per minute ([latex]\text{Lpm}[/latex]) with a decelerating flow pattern. A decelerating flow pattern means that the flow peaks at initiation and then slows down as the lungs fill. This setting will work for the overwhelming majority of adult patients; however, with practice you should always try to adjust ventilation settings based on individual patient needs. The flow waveform can also take different patterns such as square (constant) and ascending. When volume is the control variable, the volume and flow waveforms are unaffected by changes in patient’s lung characteristics. Because volume and flow are closely related, control of one allows the control of the other.

The pressure waveform may change depending on lung mechanics.

A word of caution: the higher the flows used, the higher the pressure you will be pushing into the lungs. Increasing the flows can cause large spikes in pressure that can cause damage to the lungs (barotrauma).

|

Setting |

Patient Status |

Initial Setting |

|---|---|---|

| Flow | Adult patients (except below) | [latex]65\text{ Lpm}[/latex], decelerating pattern |

| Flow | Patients triggering additional breaths, who appear to be gasping and causing the ventilator to alarm | Titrate flow up (increase by [latex]5\text{ Lpm}[/latex] at a time) while monitoring pressure. |

Watch your peak pressures and keep them below [latex]35\text{ cmH}_2\text{O (PIP}<35\text{ cmH}_2\text{O)}[/latex].

“Volume Control Specific Settings: Tidal Volume and Flow” from Basic Principles of Mechanical Ventilation by Melody Bishop, © Sault College is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.