6.6 Mercury

The planet Mercury is similar to the Moon in many ways. Like the Moon, it has no atmosphere, and its surface is heavily cratered. As described later in this chapter, it also shares with the Moon the likelihood of a violent birth.

Mercury is the nearest planet to the Sun, and, in accordance with Kepler’s third law, it has the shortest period of revolution about the Sun (88 of our days) and the highest average orbital speed (48 kilometres per second). It is appropriately named for the fleet-footed messenger god of the Romans. Because Mercury remains close to the Sun, it can be difficult to pick out in the sky. As you might expect, it’s best seen when its eccentric orbit takes it as far from the Sun as possible.

The semimajor axis of Mercury’s orbit—that is, the planet’s average distance from the Sun—is 58 million kilometres, or 0.39 AU. However, because its orbit has the high eccentricity of 0.206, Mercury’s actual distance from the Sun varies from 46 million kilometres at perihelion to 70 million kilometres at aphelion.

Mercury’s mass is one-eighteenth that of Earth, making it the smallest terrestrial planet. Mercury is the smallest planet (except for the dwarf planets), having a diameter of 4878 kilometres, less than half that of Earth. Mercury’s density is 5.4 g/cm3, much greater than the density of the Moon, indicating that the composition of those two objects differs substantially.

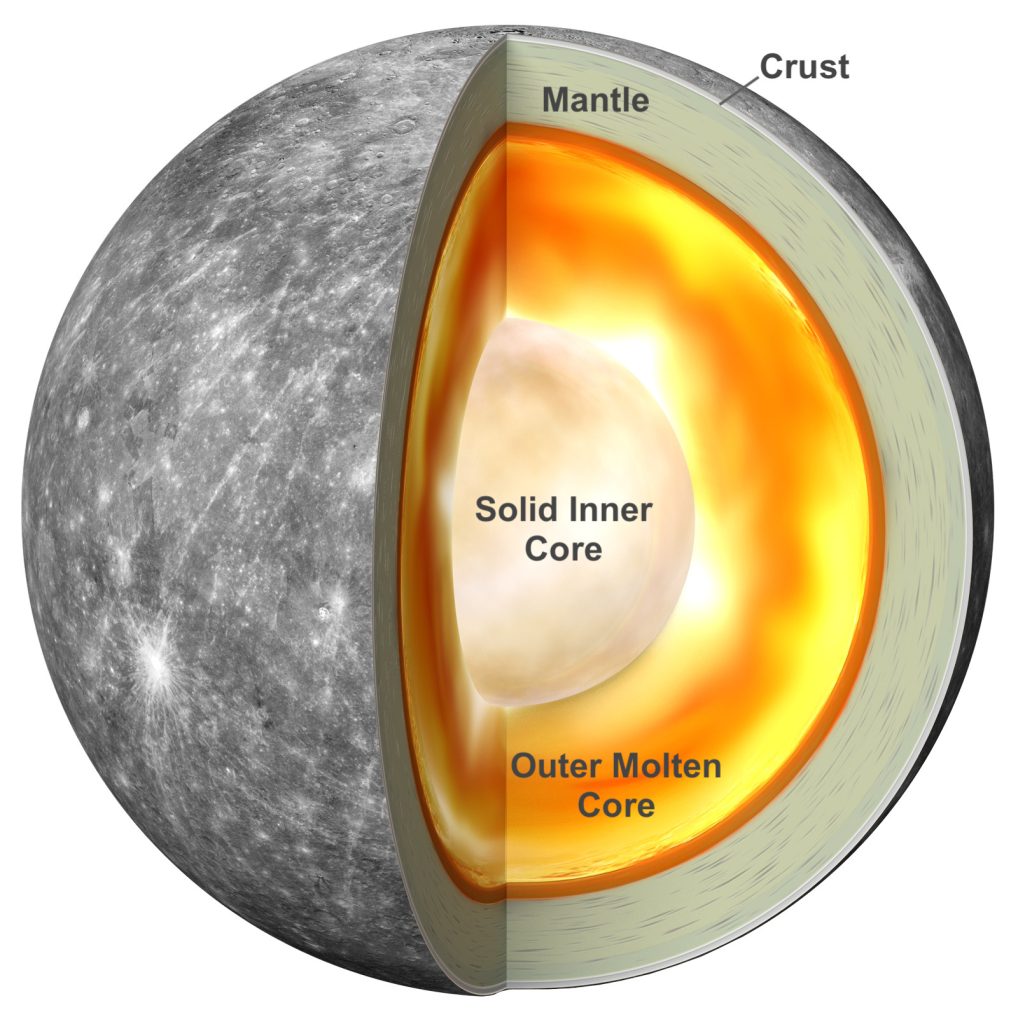

Mercury’s composition is one of the most interesting things about it and makes it unique among the planets. Mercury’s high density tells us that it must be composed largely of heavier materials such as metals. The most likely models for Mercury’s interior suggest a metallic iron-nickel core amounting to 60% of the total mass, with the rest of the planet made up primarily of silicates. The core has a diameter of 3500 kilometres and extends out to within 700 kilometres of the surface. We could think of Mercury as a metal ball the size of the Moon surrounded by a rocky crust 700 kilometres thick (Figure 6.29). Unlike the Moon, Mercury does have a weak magnetic field. The existence of this field is consistent with the presence of a large metal core, and it suggests that at least part of the core must be liquid in order to generate the observed magnetic field.

Mercury’s Internal Structure

Mercury’s internal structure by NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center, NASA Media Licence.

Example 6.2

Densities of Worlds

The average density of a body equals its mass divided by its volume. For a sphere, density is:

[latex]\begin{align*}\text{density}=\frac{\text{mass}}{\frac{4}{3}\pi R^3}\end{align*}[/latex]

Astronomers can measure both mass and radius accurately when a spacecraft flies by a body. Using the information in this chapter, we can calculate the approximate average density of the Moon.

Solution

For a sphere,

[latex]\begin{align*}\text{density}=\frac{\text{mass}}{\frac{4}{3}\pi R^3}=\frac{7.35\times 10^22\;\text{kg}}{4.2\times 5.2\times 10^18\;\text{m}^3}=3.4\times 10^3\;\text{kg/m}^3\end{align*}[/latex]

Table 6.1 gives a value of [latex]3.3\;\text{g/cm}^3[/latex], which is [latex]3.3\times 10^3\;\text{kg/m}^3[/latex].

Exercise 6.2

Using the information in this chapter, calculate the average density of Mercury. Show your work. Does your calculation agree with the figure we give in this chapter?

Solution

That matches the value given in Table 6.1 when g/cm3 is converted into kg/m3.

Mercury’s Strange Rotation

Visual studies of Mercury’s indistinct surface markings were once thought to indicate that the planet kept one face to the Sun (as the Moon does to Earth). Thus, for many years, it was widely believed that Mercury’s rotation period was equal to its revolution period of 88 days, making one side perpetually hot while the other was always cold.

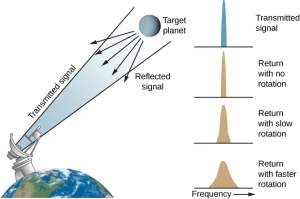

Radar observations of Mercury in the mid-1960s, however, showed conclusively that Mercury does not keep one side fixed toward the Sun. If a planet is turning, one side seems to be approaching Earth while the other is moving away from it. The resulting Doppler shift spreads or broadens the precise transmitted radar-wave frequency into a range of frequencies in the reflected signal (Figure 6.30). The degree of broadening provides an exact measurement of the rotation rate of the planet.

Doppler Radar Measures Rotation

Mercury’s period of rotation (how long it takes to turn with respect to the distant stars) is 59 days, which is just two-thirds of the planet’s period of revolution. Subsequently, astronomers found that a situation where the spin and the orbit of a planet (its year) are in a 2:3 ratio turns out to be stable.

Mercury, being close to the Sun, is very hot on its daylight side; but because it has no appreciable atmosphere, it gets surprisingly cold during the long nights. The temperature on the surface climbs to 700 K (430 °C) at noontime. After sunset, however, the temperature drops, reaching 100 K (–170 °C) just before dawn. (It is even colder in craters near the poles that receive no sunlight at all.) The range in temperature on Mercury is thus 600 K (or 600 °C), a greater difference than on any other planet.

Mercury rotates three times for each two orbits around the Sun. It is the only planet that exhibits this relationship between its spin and its orbit, and there are some interesting consequences for any observers who might someday be stationed on the surface of Mercury.

Here on Earth, we take for granted that days are much shorter than years. Therefore, the two astronomical ways of defining the local “day”—how long the planet takes to rotate and how long the Sun takes to return to the same position in the sky—are the same on Earth for most practical purposes. But this is not the case on Mercury. While Mercury rotates (spins once) in 59 Earth days, the time for the Sun to return to the same place in Mercury’s sky turns out to be two Mercury years, or 176 Earth days. (Note that this result is not intuitively obvious, so don’t be upset if you didn’t come up with it.) Thus, if one day at noon a Mercury explorer suggests to her companion that they should meet at noon the next day, this could mean a very long time apart!

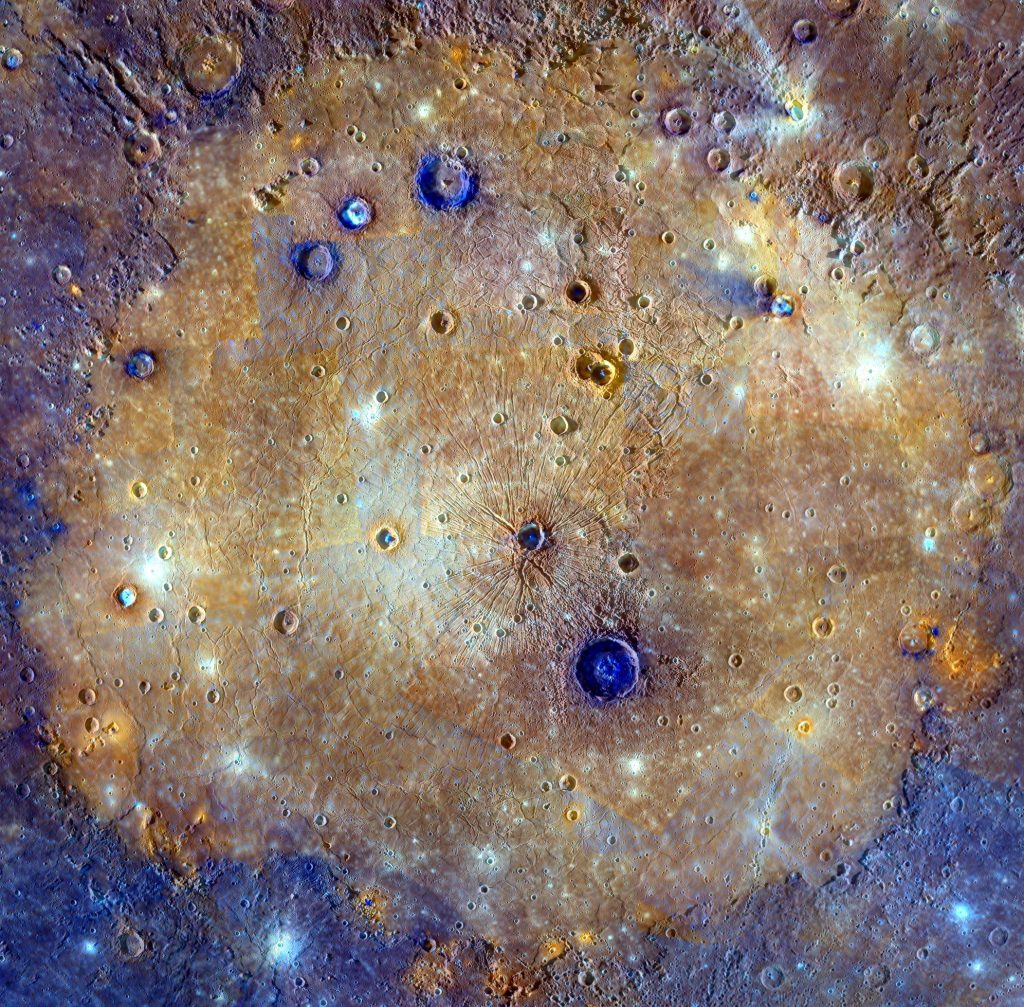

To make things even more interesting, recall that Mercury has an eccentric orbit, meaning that its distance from the Sun varies significantly during each mercurian year. By Kepler’s law, the planet moves fastest in its orbit when closest to the Sun. Let’s examine how this affects the way we would see the Sun in the sky during one 176-Earth-day cycle. We’ll look at the situation as if we were standing on the surface of Mercury in the center of a giant basin that astronomers call Caloris (Figure 6.31).

Caloris Basin

Mercury's Caloris Basin by NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Carnegie Institution of Washington, NASA Media Licence.

At the location of Caloris, Mercury is most distant from the Sun at sunrise; this means the rising Sun looks smaller in the sky (although still more than twice the size it appears from Earth). As the Sun rises higher and higher, it looks bigger and bigger; Mercury is now getting closer to the Sun in its eccentric orbit. At the same time, the apparent motion of the Sun slows down as Mercury’s faster motion in orbit begins to catch up with its rotation.

At noon, the Sun is now three times larger than it looks from Earth and hangs almost motionless in the sky. As the afternoon wears on, the Sun appears smaller and smaller, and moves faster and faster in the sky. At sunset, a full Mercury year (or 88 Earth days after sunrise), the Sun is back to its smallest apparent size as it dips out of sight. Then it takes another Mercury year before the Sun rises again. (By the way, sunrises and sunsets are much more sudden on Mercury, since there is no atmosphere to bend or scatter the rays of sunlight.)

Astronomers call locations like the Caloris Basin the “hot longitudes” on Mercury because the Sun is closest to the planet at noon, just when it is lingering overhead for many Earth days. This makes these areas the hottest places on Mercury.

We bring all this up not because the exact details of this scenario are so important but to illustrate how many of the things we take for granted on Earth are not the same on other worlds. As we’ve mentioned before, one of the best things about taking an astronomy class should be ridding you forever of any “Earth chauvinism” you might have. The way things are on our planet is just one of the many ways nature can arrange reality.

This Day on Mercury visualization shows how Mercury’s slow rotation leads to very long days and how this combines with its highly elliptical orbit to cause some unusual motions of the sun in the sky. Note the stick figure on the surface of Mercury; the Day/Night box shows what that stick figure would see in the sky.

The first close-up look at Mercury came in 1974, when the US spacecraft Mariner 10 passed 9500 kilometres from the surface of the planet and transmitted more than 2000 photographs to Earth, revealing details with a resolution down to 150 metres. Subsequently, the planet was mapped in great detail by the MESSENGER spacecraft, which was launched in 2004 and made multiple flybys of Earth, Venus, and Mercury before settling into orbit around Mercury in 2011. It ended its life in 2015, when it was commanded to crash into the surface of the planet.

Mercury’s surface strongly resembles the Moon in appearance (Figure 6.32 and Figure 6.33). It is covered with thousands of craters and larger basins up to 1300 kilometres in diameter. Some of the brighter craters are rayed, like Tycho and Copernicus on the Moon, and many have central peaks. There are also scarps (cliffs) more than a kilometer high and hundreds of kilometres long, as well as ridges and plains.

MESSENGER instruments measured the surface composition and mapped past volcanic activity. One of its most important discoveries was the verification of water ice (first detected by radar) in craters near the poles, similar to the situation on the Moon, and the unexpected discovery of organic (carbon-rich) compounds mixed with the water ice.

Scientists working with data from the MESSENGER mission put together a rotating globe of Mercury, in false colour, showing some of the variations in the composition of the planet’s surface. You can watch it spin.

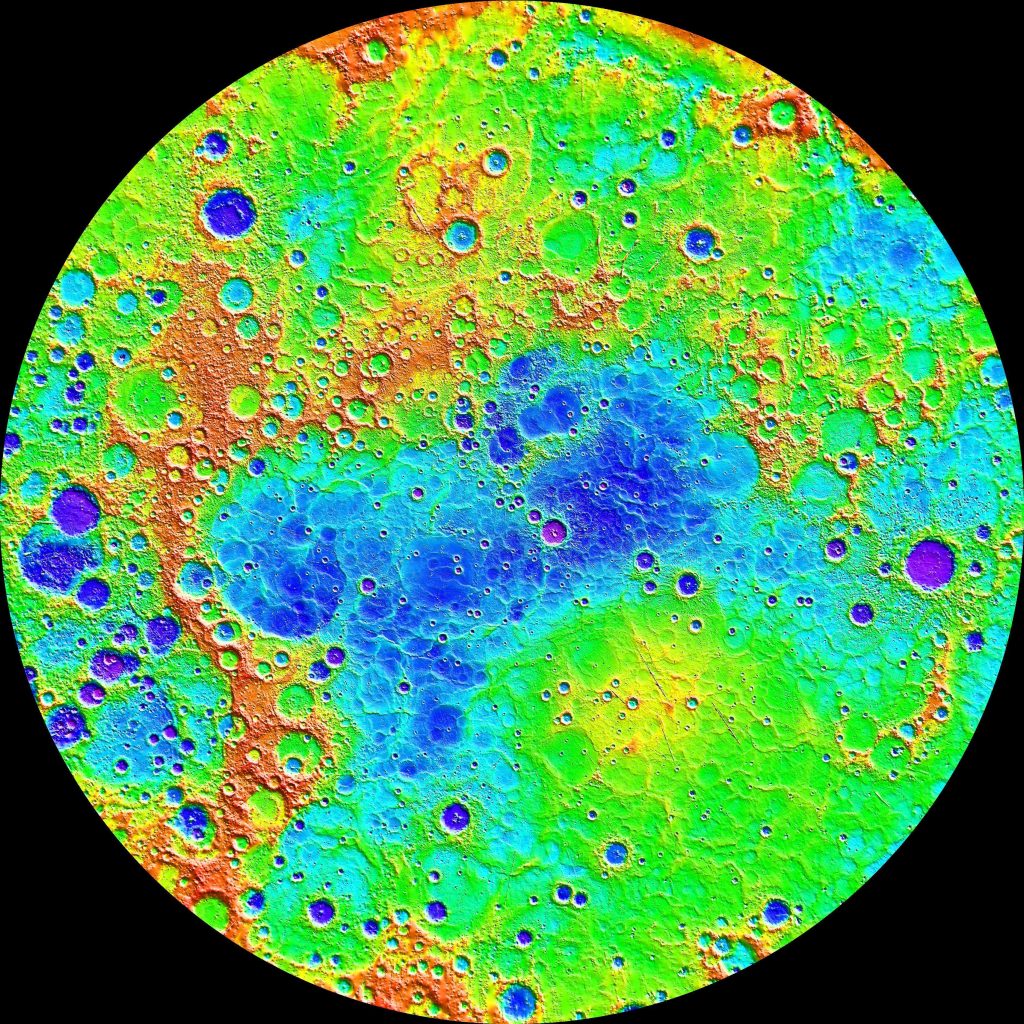

Mercury’s Topography

PIA19420: The Ups and Downs of Mercury's Topography by NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Carnegie Institution of Washington, NASA Media Licence.

Most of the mercurian features have been named in honour of artists, writers, composers, and other contributors to the arts and humanities, in contrast with the scientists commemorated on the Moon. Among the named craters are Bach, Shakespeare, Tolstoy, Van Gogh, and Scott Joplin.

There is no evidence of plate tectonics on Mercury. However, the planet’s distinctive long scarps can sometimes be seen cutting across craters; this means the scarps must have formed later than the craters (Figure 6.33). These long, curved cliffs appear to have their origin in the slight compression of Mercury’s crust. Apparently, at some point in its history, the planet shrank, wrinkling the crust, and it must have done so after most of the craters on its surface had already formed.

If the standard cratering chronology applies to Mercury, this shrinkage must have taken place during the last 4 billion years and not during the solar system’s early period of heavy bombardment.

Discovery Scarp on Mercury

Discovery Scarp by NASA/JPL/Northwestern University, NASA JPL Media Licence.

Attribution

“9.5 Mercury" from Astronomy 2e by Andrew Fraknoi, David Morrison, Sidney C. Wolff, © OpenStax – Rice University is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.