16.3 Astrobiology

Scientists today take a multidisciplinary approach to studying the origin, evolution, distribution, and ultimate fate of life in the universe; this field of study is known as astrobiology. You may also sometimes hear this field referred to as exobiology or bioastronomy. Astrobiology brings together astronomers, planetary scientists, chemists, geologists, and biologists (among others) to work on the same problems from their various perspectives.

Among the issues that astrobiologists explore are the conditions in which life arose on Earth and the reasons for the extraordinary adaptability of life on our planet. They are also involved in identifying habitable worlds beyond Earth and in trying to understand in practical terms how to look for life on those worlds. Let’s look at some of these issues in more detail.

The Building Blocks of Life

While no unambiguous evidence for life has yet been found anywhere beyond Earth, life’s chemical building blocks have been detected in a wide range of extraterrestrial environments. Meteorites have been found to contain two kinds of substances whose chemical structures mark them as having an extraterrestrial origin—amino acids and sugars. Amino acids are organic compounds that are the molecular building blocks of proteins. Proteins are key biological molecules that provide the structure and function of the body’s tissues and organs and essentially carry out the “work” of the cell. When we examine the gas and dust around comets, we also find a number of organic molecules—compounds that on Earth are associated with the chemistry of life.

Expanding beyond our solar system, one of the most interesting results of modern radio astronomy has been the discovery of organic molecules in giant clouds of gas and dust between stars. More than 100 different molecules have been identified in these reservoirs of cosmic raw material, including formaldehyde, alcohol, and others we know as important stepping stones in the development of life on Earth. Using radio telescopes and radio spectrometres, astronomers can measure the abundances of various chemicals in these clouds. We find organic molecules most readily in regions where the interstellar dust is most abundant, and it turns out these are precisely the regions where star formation (and probably planet formation) happen most easily (see Figure 16.4 below).

Cloud of Gas and Dust

PIA22567: Cat’s Paw Image 2 by NASA/JPL-Caltech, NASA Media Licence.

Clearly the early Earth itself produced some of the molecular building blocks of life. Since the early 1950s, scientists have tried to duplicate in their laboratories the chemical pathways that led to life on our planet. In a series of experiments known as the Miller-Urey experiments, pioneered by Stanley Miller and Harold Urey at the University of Chicago, biochemists have simulated conditions on early Earth and have been able to produce some of the fundamental building blocks of life, including those that form proteins and other large biological molecules known as nucleic acids (which we will discuss shortly).

Although these experiments produced encouraging results, there are some problems with them. The most interesting chemistry from a biological perspective takes place with hydrogen-rich or reducing gases, such as ammonia and methane. However, the early atmosphere of Earth was probably dominated by carbon dioxide (as Venus’ and Mars’ atmospheres still are today) and may not have contained an abundance of reducing gases comparable to that used in Miller-Urey type experiments. Hydrothermal vents—seafloor systems in which ocean water is superheated and circulated through crustal or mantle rocks before reemerging into the ocean—have also been suggested as potential contributors of organic compounds on the early Earth, and such sources would not require Earth to have an early reducing atmosphere.

Both earthly and extraterrestrial sources may have contributed to Earth’s early supply of organic molecules, although we have more direct evidence for the latter. It is even conceivable that life itself originated elsewhere and was seeded onto our planet—although this, of course, does not solve the problem of how that life originated to begin with.

The Origin and Early Evolution of Life

The carbon compounds that form the chemical basis of life may be common in the universe, but it is still a giant step from these building blocks to a living cell. Even the simplest molecules of the genes (the basic functional units that carry the genetic, or hereditary, material in a cell) contain millions of molecular units, each arranged in a precise sequence. Furthermore, even the most primitive life required two special capabilities: a means of extracting energy from its environment, and a means of encoding and replicating information in order to make faithful copies of itself. Biologists today can see ways that either of these capabilities might have formed in a natural environment, but we are still a long way from knowing how the two came together in the first life-forms.

We have no solid evidence for the pathway that led to the origin of life on our planet except for whatever early history may be retained in the biochemistry of modern life. Indeed, we have very little direct evidence of what Earth itself was like during its earliest history—our planet is so effective at resurfacing itself through plate tectonics that very few rocks remain from this early period. In the earlier chapter on Terrestrial Planets, you learned that Earth was subjected to a heavy bombardment—a period of large impact events—some 3.8 to 4.1 billion years ago. Large impacts would have been energetic enough to heat-sterilize the surface layers of Earth, so that even if life had begun by this time, it might well have been wiped out.

When the large impacts ceased, the scene was set for a more peaceful environment on our planet. If the oceans of Earth contained accumulated organic material from any of the sources already mentioned, the ingredients were available to make living organisms. We do not understand in any detail the sequence of events that led from molecules to biology, but there is fossil evidence of microbial life in 3.5-billion-year-old rocks, and possible (debated) evidence for life as far back as 3.8 billion years.

Life as we know it employs two main molecular systems: the functional molecules known as proteins, which carry out the chemical work of the cell, and information-containing molecules of DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid) that store information about how to create the cell and its chemical and structural components. The origin of life is sometimes considered a “chicken and egg problem” because, in modern biology, neither of these systems works without the other. It is our proteins that assemble DNA strands in the precise order required to store information, but the proteins are created based on information stored in DNA. Which came first? Some origin of life researchers believe that prebiotic chemistry was based on molecules that could both store information and do the chemical work of the cell. It has been suggested that RNA (ribonucleic acid), a molecule that aids in the flow of genetic information from DNA to proteins, might have served such a purpose. The idea of an early “RNA world” has become increasingly accepted, but a great deal remains to be understood about the origin of life.

Perhaps the most important innovation in the history of biology, apart from the origin of life itself, was the discovery of the process of photosynthesis, the complex sequence of chemical reactions through which some living things can use sunlight to manufacture products that store energy (such as carbohydrates), releasing oxygen as one by-product. Previously, life had to make do with sources of chemical energy available on Earth or delivered from space. But the abundant energy available in sunlight could support a larger and more productive biosphere, as well as some biochemical reactions not previously possible for life. One of these was the production of oxygen (as a waste product) from carbon dioxide, and the increase in atmospheric levels of oxygen about 2.4 billion years ago means that oxygen-producing photosynthesis must have emerged and become globally important by this time. In fact, it is likely that oxygen-producing photosynthesis emerged considerably earlier.

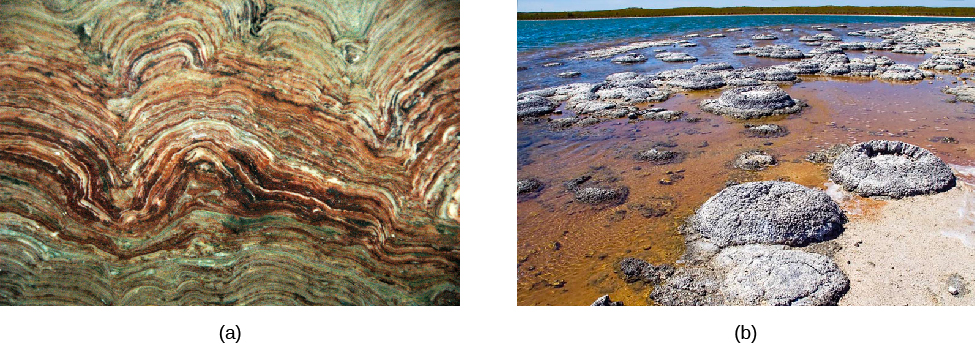

Some forms of chemical evidence contained in ancient rocks, such as the solid, layered rock formations known as stromatolites, are thought to be the fossils of oxygen-producing photosynthetic bacteria in rocks that are almost 3.5 billion years old (Figure 16.5). It is generally thought that a simpler form of photosynthesis that does not produce oxygen (and is still used by some bacteria today) probably preceded oxygen-producing photosynthesis, and there is strong fossil evidence that one or the other type of photosynthesis was functioning on Earth at least as far back as 3.4 billion years ago.

Stromatolites Preserve the Earliest Physical Representation of Life on Earth

Stromatolites by James St. John, CC BY 2.0 (b) This more recent example is in Lake Thetis, also in Western Australia.

Stromatolites at Lake Thetis by Ruth Ellison, CC BY 2.0

The free oxygen produced by photosynthesis began accumulating in our atmosphere about 2.4 billion years ago. The interaction of sunlight with oxygen can produce ozone (which has three atoms of oxygen per molecule, as compared to the two atoms per molecule in the oxygen we breathe), which accumulated in a layer high in Earth’s atmosphere. As it does on Earth today, this ozone provided protection from the Sun’s damaging ultraviolet radiation. This allowed life to colonize the landmasses of our planet instead of remaining only in the ocean.

The rise in oxygen levels was deadly to some microbes because, as a highly reactive chemical, it can irreversibly damage some of the biomolecules that early life had developed in the absence of oxygen. For other microbes, it was a boon: combining oxygen with organic matter or other reduced chemicals generates a lot of energy—you can see this when a log burns, for example—and many forms of life adopted this way of living. This new energy source made possible a great proliferation of organisms, which continued to evolve in an oxygen-rich environment.

The details of that evolution are properly the subject of biology courses, but the process of evolution by natural selection (survival of the fittest) provides a clear explanation for the development of Earth’s remarkable variety of life-forms. It does not, however, directly solve the mystery of life’s earliest beginnings. We hypothesize that life will arise whenever conditions are appropriate, but this hypothesis is just another form of the Copernican principle. We now have the potential to address this hypothesis with observations. If a second example of life is found in our solar system or a nearby star, it would imply that life emerges commonly enough that the universe is likely filled with biology. To make such observations, however, we must first decide where to focus our search.

Habitable Environments

Among the staggering number of objects in our solar system, Galaxy, and universe, some may have conditions suitable for life, while others do not. Understanding what conditions and features make a habitable environment—an environment capable of hosting life—is important both for understanding how widespread habitable environments may be in the universe and for focusing a search for life beyond Earth. Here, we discuss habitability from the perspective of the life we know. We will explore the basic requirements of life and, in the following section, consider the full range of environmental conditions on Earth where life is found. While we can’t entirely rule out the possibility that other life-forms might have biochemistry based on alternatives to carbon and liquid water, such life “as we don’t know it” is still completely speculative. In our discussion here, we are focusing on habitability for life that is chemically similar to that on Earth.

Life requires a solvent (a liquid in which chemicals can dissolve) that enables the construction of biomolecules and the interactions between them. For life as we know it, that solvent is water, which has a variety of properties that are critical to how our biochemistry works. Water is abundant in the universe, but life requires that water be in liquid form (rather than ice or gas) in order to properly fill its role in biochemistry. That is the case only within a certain range of temperatures and pressures—too high or too low in either variable, and water takes the form of a solid or a gas. Identifying environments where water is present within the appropriate range of temperature and pressure is thus an important first step in identifying habitable environments. Indeed, a “follow the water” strategy has been, and continues to be, a key driver in the exploration of planets both within and beyond our solar system.

Our biochemistry is based on molecules made of carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, oxygen, phosphorus, and sulfur. Carbon is at the core of organic chemistry. Its ability to form four bonds, both with itself and with the other elements of life, allows for the formation of a vast number of potential molecules on which to base biochemistry. The remaining elements contribute structure and chemical reactivity to our biomolecules, and form the basis of many of the interactions among them. These “biogenic elements,” sometimes referred to with the acronym CHNOPS (carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, oxygen, phosphorus, and sulfur), are the raw materials from which life is assembled, and an accessible supply of them is a second requirement of habitability.

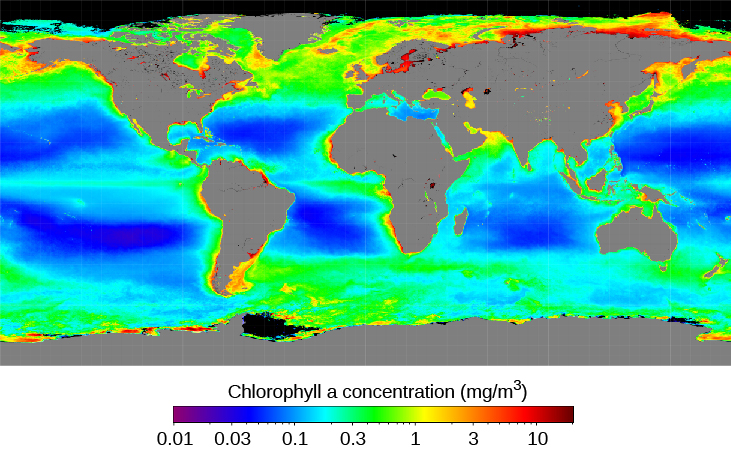

As we learned in previous chapters on nuclear fusion and the life story of the stars, carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, phosphorus, and sulfur are all formed by fusion within stars and then distributed out into their galaxy as those stars die. But how they are distributed among the planets that form within a new star system, in what form, and how chemical, physical, and geological processes on those planets cycle the elements into structures that are accessible to biology, can have significant impacts on the distribution of life. In Earth’s oceans, for example, the abundance of phytoplankton (simple organisms that are the base of the ocean food chain) in surface waters can vary by a thousand-fold because the supply of nitrogen differs from place to place (Figure 16.6). Understanding what processes control the accessibility of elements at all scales is thus a critical part of identifying habitable environments.

Chlorophyll Abundance

Seasonal Chlorophyll Comparison by NASA, NASA Licence)

With these first two requirements, we have the elemental raw materials of life and a solvent in which to assemble them into the complicated molecules that drive our biochemistry. But carrying out that assembly and maintaining the complicated biochemical machinery of life takes energy. You fulfill your own requirement for energy every time you eat food or take a breath, and you would not live for long if you failed to do either on a regular basis. Life on Earth makes use of two main types of energy: for you, these are the oxygen in the air you breathe and the organic molecules in your food. But life overall can use a much wider array of chemicals and, while all animals require oxygen, many bacteria do not. One of the earliest known life processes, which still operates in some modern microorganisms, combines hydrogen and carbon dioxide to make methane, releasing energy in the process. There are microorganisms that “breathe” metals that would be toxic to us, and even some that breathe in sulfur and breathe out sulfuric acid. Plants and photosynthetic microorganisms have also evolved mechanisms to use the energy in light directly.

Water in the liquid phase, the biogenic elements, and energy are the fundamental requirements for habitability. But are there additional environmental constraints? We consider this in the next section.

Grand Prismatic Spring in Yellowstone National Park

Grand Prismatic by Mike Goad, Pixabay Content Licence

Life in Extreme Conditions

At a chemical level, life consists of many types of molecules that interact with one another to carry out the processes of life. In addition to water, elemental raw materials, and energy, life also needs an environment in which those complicated molecules are stable (don’t break down before they can do their jobs) and their interactions are possible. Your own biochemistry works properly only within a very narrow range of about 10 °C in body temperature and two-tenths of a unit in blood pH (pH is a numerical measure of acidity, or the amount of free hydrogen ions). Beyond those limits, you are in serious danger.

Life overall must also have limits to the conditions in which it can properly work but, as we will see, they are much broader than human limits. The resources that fuel life are distributed across a very wide range of conditions. For example, there is abundant chemical energy to be had in hot springs that are essentially boiling acid (see Figure 16.7 above). This provides ample incentive for evolution to fill as much of that range with life as is biochemically possible. An organism (usually a microbe) that tolerates or even thrives under conditions that most of the life around us would consider hostile, such as very high or low temperature or acidity, is known as an extremophile (where the suffix -phile means “lover of”). Let’s have a look at some of the conditions that can challenge life and the organisms that have managed to carve out a niche at the far reaches of possibility.

Both high and low temperatures can cause a problem for life. As a large organism, you are able to maintain an almost constant body temperature whether it is colder or warmer in the environment around you. But this is not possible at the tiny size of microorganisms; whatever the temperature in the outside world is also the temperature of the microbe, and its biochemistry must be able to function at that temperature. High temperatures are the enemy of complexity—increasing thermal energy tends to break apart big molecules into smaller and smaller bits, and life needs to stabilize the molecules with stronger bonds and special proteins. But this approach has its limits.

Nevertheless, as noted earlier, high-temperature environments like hot springs and hydrothermal vents often offer abundant sources of chemical energy and therefore drive the evolution of organisms that can tolerate high temperatures (see Figure 16.8); such an organism is called a thermophile. Currently, the high temperature record holder is a methane-producing microorganism that can grow at 122 °C, where the pressure also is so high that water still does not boil. That’s amazing when you think about it. We cook our food—meaning, we alter the chemistry and structure of its biomolecules—by boiling it at a temperature of 100 °C. In fact, food begins to cook at much lower temperatures than this. And yet, there are organisms whose biochemistry remains intact and operates just fine at temperatures 20 degrees higher.

Hydrothermal Vent on the Sea Floor

expl2366 by NOAA Photo Library, CC BY 2.0

Cold can also be a problem, in part because it slows down metabolism to very low levels, but also because it can cause physical changes in biomolecules. Cell membranes—the molecular envelopes that surround cells and allow their exchange of chemicals with the world outside—are basically made of fatlike molecules. And just as fat congeals when it cools, membranes crystallize, changing how they function in the exchange of materials in and out of the cell. Some cold-adapted cells (called psychrophiles) have changed the chemical composition of their membranes in order to cope with this problem; but again, there are limits. Thus far, the coldest temperature at which any microbe has been shown to reproduce is about –25 ºC.

Conditions that are very acidic or alkaline can also be problematic for life because many of our important molecules, like proteins and DNA, are broken down under such conditions. For example, household drain cleaner, which does its job by breaking down the chemical structure of things like hair clogs, is a very alkaline solution. The most acid-tolerant organisms (acidophiles) are capable of living at pH values near zero—about ten million times more acidic than your blood (Figure 16.9 below). At the other extreme, some alkaliphiles can grow at pH levels of about 13, which is comparable to the pH of household bleach and almost a million times more alkaline than your blood.

Spain’s Rio Tinto

The Rio Tinto in 2006 by Riotinto2006, CC0 1.0

High levels of salts in the environment can also cause a problem for life because the salt blocks some cellular functions. Humans recognized this centuries ago and began to salt-cure food to keep it from spoiling—meaning, to keep it from being colonized by microorganisms. Yet some microbes have evolved to grow in water that is saturated in sodium chloride (table salt)—about ten times as salty as seawater (Figure 16.10 below).

Salt Ponds

STS111-376-3 by NASA, NASA Licence

Very high pressures can literally squeeze life’s biomolecules, causing them to adopt more compact forms that do not work very well. But we still find life—not just microbial, but even animal life—at the bottoms of our ocean trenches, where pressures are more than 1000 times atmospheric pressure. Many other adaptions to environmental “extremes” are also known. There is even an organism, Deinococcus radiodurans, that can tolerate ionizing radiation (such as that released by radioactive elements) a thousand times more intense than you would be able to withstand. It is also very good at surviving extreme desiccation (drying out) and a variety of metals that would be toxic to humans.

From many such examples, we can conclude that life is capable of tolerating a wide range of environmental extremes—so much so that we have to work hard to identify places where life can’t exist. A few such places are known—for example, the waters of hydrothermal vents at over 300 °C appear too hot to support any life—and finding these places helps define the possibility for life elsewhere. The study of extremophiles over the last few decades has expanded our sense of the range of conditions life can survive and, in doing so, has made many scientists more optimistic about the possibility that life might exist beyond Earth.

Attribution

“30.2 Astrobiology” from Douglas College Astronomy 1105 by Douglas College Department of Physics and Astronomy, is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted. Adapted from Astronomy 2e.