13.3 Collisions and Mergers

One of the conclusions astronomers have reached from studying distant galaxies is that collisions and mergers of whole galaxies play a crucial role in determining how galaxies acquired the shapes and sizes we see today. Only a few of the nearby galaxies are currently involved in collisions, but detailed studies of those tell us what to look for when we seek evidence of mergers in very distant and very faint galaxies. These in turn give us important clues about the different evolutionary paths galaxies have taken over cosmic time. Let’s examine in more detail what happens when two galaxies collide.

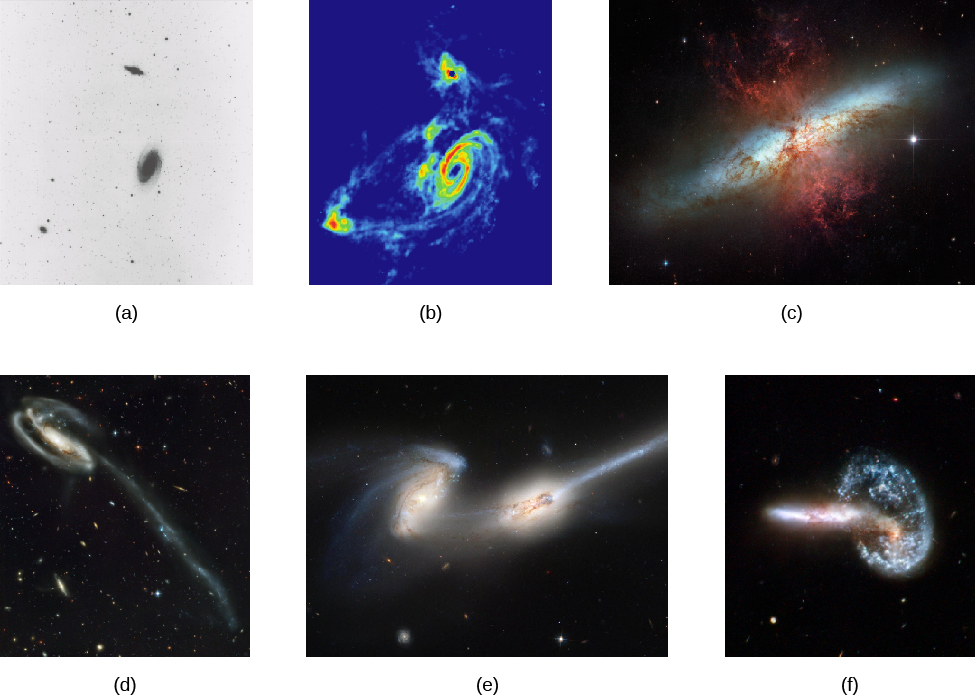

The images below show a dynamic views of two galaxies that are colliding. The stars themselves in this pair of galaxies will not be affected much by this cataclysmic event. (See the Astronomy Basics feature box “Why Galaxies Collide but Stars Rarely Do” below the image) Since there is a lot of space between the stars, a direct collision between two stars is very unlikely. However, the orbits of many of the stars will be changed as the two galaxies move through each other, and the change in orbits can totally alter the appearance of the interacting galaxies. A gallery of interesting colliding galaxies is shown in Figure 13.4. Great rings, huge tendrils of stars and gas, and other complex structures can form in such cosmic collisions. Indeed, these strange shapes are the signposts that astronomers use to identify colliding galaxies.

Gallery of Interacting Galaxies

Credit a, b: Figure 8.11 by NRAO/AUI, CC BY 4.0.

Credit c: Messier 82 (The Cigar Galaxy) by NASA, ESA, and The Hubble Heritage Team (STScI/AURA), NASA Media License.

Credit d: Rich Background of Galaxies Behind the Tadpole Galaxy by NASA, H. Ford (JHU), G. Illingworth (UCSC/LO), M.Clampin (STScI), G. Hartig (STScI), the ACS Science Team, and ESA, ESA Standard License.

Credit e: The Mice (NGC 4676): Colliding Galaxies With Tails of Stars and Gas by NASA, H. Ford (JHU), G. Illingworth (UCSC/LO), M.Clampin (STScI), G. Hartig (STScI), the ACS Science Team, and ESA, NASA Media License.

Credit f: Arp 148 by NASA, ESA, the Hubble Heritage (STScI/AURA)-ESA/Hubble Collaboration, and A. Evans (University of Virginia, Charlottesville/NRAO/Stony Brook University), NASA Media License.

Why Galaxies Collide but Stars Rarely Do

Throughout this book we have emphasized the large distances between objects in space. You might therefore have been surprised to hear about collisions between galaxies. Yet (except at the very cores of galaxies) we have not worried at all about stars inside a galaxy colliding with each other. Let’s see why there is a difference.

The reason is that stars are pitifully small compared to the distances between them. Let’s use our Sun as an example. The Sun is about 1.4 million kilometres wide, but is separated from the closest other star by about 4 light-years, or about 38 trillion kilometres. In other words, the Sun is 27 million of its own diametres from its nearest neighbour. If the Sun were a grapefruit in New York City, the nearest star would be another grapefruit in San Francisco. This is typical of stars that are not in the nuclear bulge of a galaxy or inside star clusters. Let’s contrast this with the separation of galaxies.

The visible disk of the Milky Way is about 100,000 light-years in diameter. We have three satellite galaxies that are just one or two Milky Way diametres away from us (and will probably someday collide with us). The closest major spiral is the Andromeda Galaxy (M31), about 2.4 million light-years away. If the Milky Way were a pancake at one end of a big breakfast table, M31 would be another pancake at the other end of the same table. Our nearest large galaxy neighbour is only 24 of our Galaxy’s diametres from us, and it will begin to crash into the Milky Way in about 3 billion years.

Galaxies in rich clusters are even closer together than those in our neighbourhood. Thus, the chances of galaxies colliding are far greater than the chances of stars in the disk of a galaxy colliding. And we should note that the difference between the separation of galaxies and stars also means that when galaxies do collide, their stars almost always pass right by each other like smoke passing through a screen door.

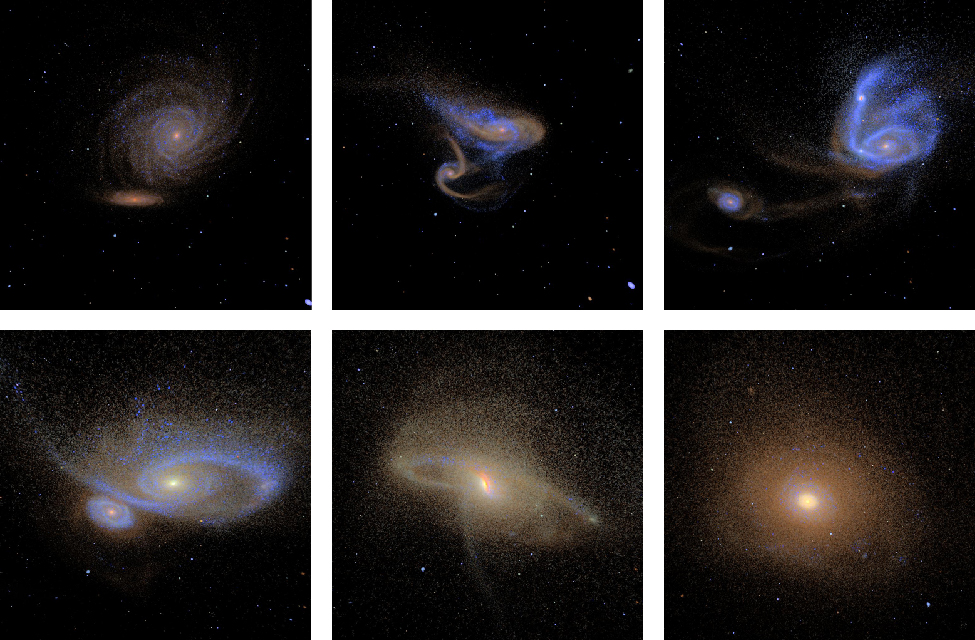

The details of galaxy collisions are complex, and the process can take hundreds of millions of years. Thus, collisions are best simulated on a computer as shown in Figure 13.5, where astronomers can calculate the slow interactions of stars, and clouds of gas and dust, via gravity. These calculations show that if the collision is slow, the colliding galaxies may coalesce to form a single galaxy.

Computer Simulation of a Galaxy Collision

Simulated Images of Merging Galaxies by P. Jonsson (Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics), G. Novak (Princeton University), and T. J. Cox (Carnegie Observatories), NASA Media License.

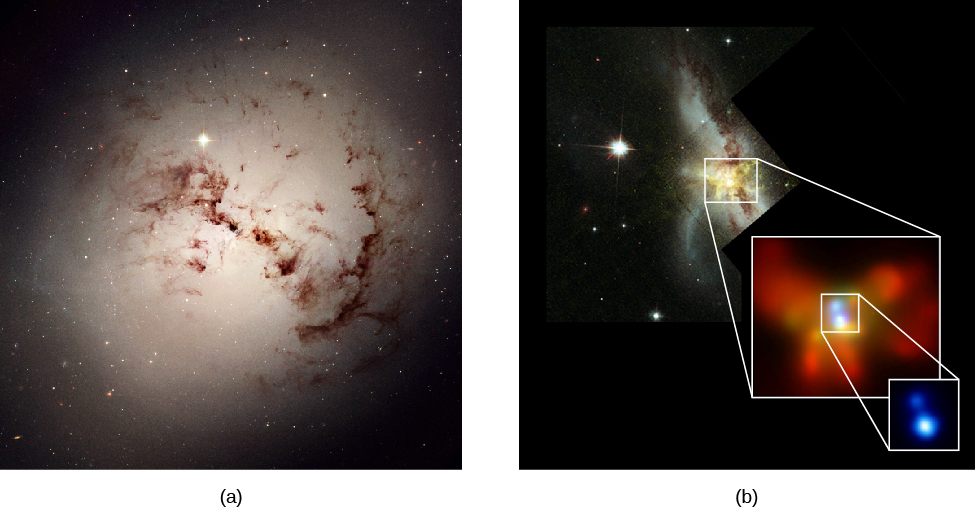

When two galaxies of equal size are involved in a collision, we call such an interaction a merger (the term applied in the business world to two equal companies that join forces). But small galaxies can also be swallowed by larger ones—a process astronomers have called, with some relish, galactic cannibalism, pictured in Figure 13.6.

Galactic Cannibalism

Credit a: The Dusty Galaxy NGC 1316 by NASA, ESA, and The Hubble Heritage Team (STScI/AURA), NASA Media License.

Credit b: The Supermassive Black Holes of NGC 6240 and NGC 6240 by X-ray: NASA/CXC/MPE/S.Komossa et al.; Optical: NASA/STScI/R.P.van der Marel & J.Gerssen), NASA Media License.

The very large elliptical galaxies probably form by cannibalizing a variety of smaller galaxies in their clusters. These “monster” galaxies frequently possess more than one nucleus and have probably acquired their unusually high luminosities by swallowing nearby galaxies. The multiple nuclei are the remnants of their victims ([image above of the cannibal galaxies). Many of the large, peculiar galaxies that we observe also owe their chaotic shapes to past interactions. Slow collisions and mergers can even transform two or more spiral galaxies into a single elliptical galaxy.

A change in shape is not all that happens when galaxies collide. If either galaxy contains interstellar matter, the collision can compress the gas and trigger an increase in the rate at which stars are being formed—by as much as a factor of 100. Astronomers call this abrupt increase in the number of stars being formed a starburst, and the galaxies in which the increase occurs are termed starburst galaxies, shown in Figure 13.7. In some interacting galaxies, star formation is so intense that all the available gas is exhausted in only a few million years; the burst of star formation is clearly only a temporary phenomenon. While a starburst is going on, however, the galaxy where it is taking place becomes much brighter and much easier to detect at large distances.

Starburst Associated with Colliding Galaxies

Credit a: Stephan’s Quintet by NASA, ESA, and the Hubble SM4 ERO Team, NASA Media License.

Credit b: Image by NASA/JPL-Caltech/STScI, NASA Media License.

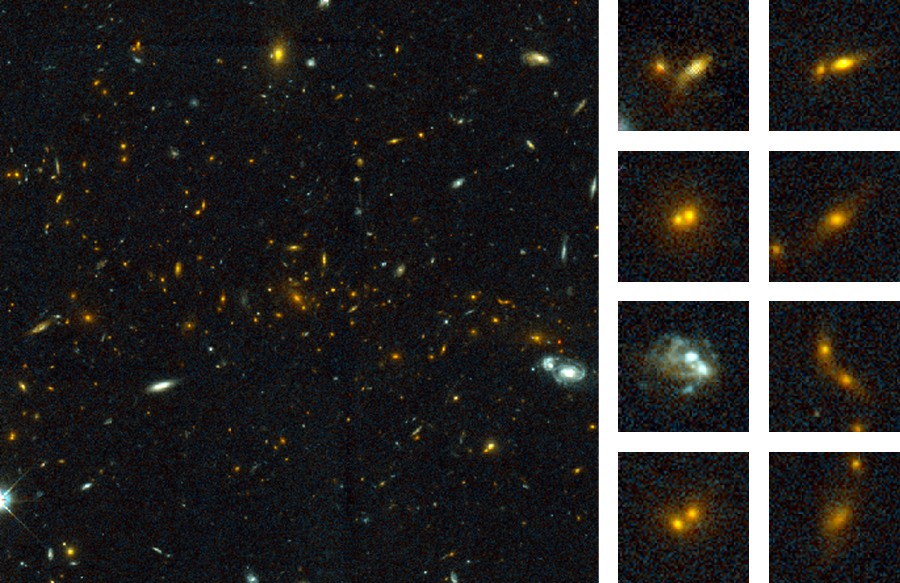

When astronomers finally had the tools to examine a significant number of galaxies that emitted their light 11 to 12 billion years ago, they found that these very young galaxies often resemble nearby starburst galaxies that are involved in mergers: they also have multiple nuclei and peculiar shapes, they are usually clumpier than normal galaxies today, with multiple intense knots and lumps of bright starlight, and they have higher rates of star formation than isolated galaxies. They also contain lots of blue, young, type O and B stars, as do nearby merging galaxies.

Galaxy mergers in today’s universe are rare. Only about five percent of nearby galaxies are currently involved in interactions. Interactions were much more common billions of years ago, some shown in Figure 13.8, and helped build up the “more mature” galaxies we see in our time. Clearly, interactions of galaxies have played a crucial role in their evolution.

Collisions of Galaxies in a Distant Cluster

MS 1054-03 & merging galaxies by Pieter van Dokkum, Marijn Franx (University of Groningen/Leiden), ESA and NASA, NASA Media License.

Attribution

“28.2 Galaxy Mergers and Active Galactic Nuclei” from Douglas College Astronomy 1105 by Douglas College Department of Physics and Astronomy, is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted. Adapted from Astronomy 2e.