11.6 White Dwarfs

In the last section, we left the life story of a star with a mass like the Sun’s just after it had climbed up to the red-giant region of the H–R diagram for a second time and had shed some of its outer layers to form a planetary nebula. Recall that during this time, the core of the star was undergoing an “energy crisis.” Earlier in its life, during a brief stable period, helium in the core had gotten hot enough to fuse into carbon (and oxygen). But after this helium was exhausted, the star’s core had once more found itself without a source of pressure to balance gravity and so had begun to contract.

This collapse is the final event in the life of the core. Because the star’s mass is relatively low, it cannot push its core temperature high enough to begin another round of fusion (in the same way larger-mass stars can). The core continues to shrink until it reaches a density equal to nearly a million times the density of water! That is 200,000 times greater than the average density of Earth. At this extreme density, a new and different way for matter to behave kicks in and helps the star achieve a final state of equilibrium. In the process, what remains of the star becomes a white dwarf.

Because white dwarfs are far denser than any substance on Earth, the matter inside them behaves in a very unusual way—unlike anything we know from everyday experience. At this high density, gravity is incredibly strong and tries to shrink the star still further, but all the electrons resist being pushed closer together and set up a powerful pressure inside the core. This pressure is the result of the fundamental rules that govern the behaviour of electrons. According to these rules (known to physicists as the Pauli exclusion principle), which have been verified in studies of atoms in the laboratory, no two electrons can be in the same place at the same time doing the same thing. We specify the place of an electron by its position in space, and we specify what it is doing by its motion and the way it is spinning.

The temperature in the interior of a star is always so high that the atoms are stripped of virtually all their electrons. For most of a star’s life, the density of matter is also relatively low, and the electrons in the star are moving rapidly. This means that no two of them will be in the same place moving in exactly the same way at the same time. But this all changes when a star exhausts its store of nuclear energy and begins its final collapse.

As the star’s core contracts, electrons are squeezed closer and closer together. Eventually, a star like the Sun becomes so dense that further contraction would in fact require two or more electrons to violate the rule against occupying the same place and moving in the same way. Such a dense gas is said to be degenerate (a term coined by physicists and not related to the electron’s moral character). The electrons in a degenerate gas resist further crowding with tremendous pressure. (It’s as if the electrons said, “You can press inward all you want, but there is simply no room for any other electrons to squeeze in here without violating the rules of our existence.”)

The degenerate electrons do not require an input of heat to maintain the pressure they exert, and so a star with this kind of structure, if nothing disturbs it, can last essentially forever. (Note that the repulsive force between degenerate electrons is different from, and much stronger than, the normal electrical repulsion between charges that have the same sign.)

The electrons in a degenerate gas do move about, as do particles in any gas, but not with a lot of freedom. A particular electron cannot change position or momentum until another electron in an adjacent stage gets out of the way. The situation is much like that in the parking lot after a big football game. Vehicles are closely packed, and a given car cannot move until the one in front of it moves, leaving an empty space to be filled.

Of course, the dying star also has atomic nuclei in it, not just electrons, but it turns out that the nuclei must be squeezed to much higher densities before their quantum nature becomes apparent. As a result, in white dwarfs, the nuclei do not exhibit degeneracy pressure. Hence, in the white dwarf stage of stellar evolution, it is the degeneracy pressure of the electrons, and not of the nuclei, that halts the collapse of the core.

White dwarfs, then, are stable, compact objects with electron-degenerate cores that cannot contract any further. Calculations showing that white dwarfs are the likely end state of low-mass stars were first carried out by the Indian-American astrophysicist Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar. He was able to show how much a star will shrink before the degenerate electrons halt its further contraction and hence what its final diameter will be.

When Chandrasekhar made his calculation about white dwarfs, he found something very surprising: the radius of a white dwarf shrinks as the mass in the star increases (the larger the mass, the more tightly packed the electrons can become, resulting in a smaller radius). According to the best theoretical models, a white dwarf with a mass of about 1.4 MSun or larger would have a radius of zero. What the calculations are telling us is that even the force of degenerate electrons cannot stop the collapse of a star with more mass than this. The maximum mass that a star can end its life with and still become a white dwarf—1.4 MSun—is called the Chandrasekhar limit. Stars with end-of-life masses that exceed this limit have a different kind of end in store—one that we will explore in the next section.

Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar

Born in 1910 in Lahore, India, Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar (known as Chandra to his friends and colleagues) grew up in a home that encouraged scholarship and an interest in science. His uncle, C. V. Raman, was a physicist who won the 1930 Nobel Prize. A precocious student, Chandra tried to read as much as he could about the latest ideas in physics and astronomy, although obtaining technical books was not easy in India at the time. He finished college at age 19 and won a scholarship to study in England. It was during the long boat voyage to get to graduate school that he first began doing calculations about the structure of white dwarf stars.

Chandra developed his ideas during and after his studies as a graduate student, showing—as we have discussed—that white dwarfs with masses greater than 1.4 times the mass of the Sun cannot exist and that the theory predicts the existence of other kinds of stellar corpses. He wrote later that he felt very shy and lonely during this period, isolated from students, afraid to assert himself, and sometimes waiting for hours to speak with some of the famous professors he had read about in India. His calculations soon brought him into conflict with certain distinguished astronomers, including Sir Arthur Eddington, who publicly ridiculed Chandra’s ideas. At a number of meetings of astronomers, such leaders in the field as Henry Norris Russell refused to give Chandra the opportunity to defend his ideas, while allowing his more senior critics lots of time to criticize them.

Yet Chandra persevered, writing books and articles elucidating his theories, which turned out not only to be correct, but to lay the foundation for much of our modern understanding of the death of stars. In 1983, he received the Nobel Prize in physics for this early work.

In 1937, Chandra came to the United States and joined the faculty at the University of Chicago, where he remained for the rest of his life. There he devoted himself to research and teaching, making major contributions to many fields of astronomy, from our understanding of the motions of stars through the Galaxy to the behaviour of the bizarre objects called black holes. In 1999, NASA named its sophisticated orbiting X-ray telescope (designed in part to explore such stellar corpses) the Chandra X-ray Observatory.

S. Chandrasekhar (1910–1995)

Portrait of a young Chandrasekhar by American Institute of Physics, Public Domain

Chandra spent a great deal of time with his graduate students, supervising the research of more than 50 PhDs during his life. He took his teaching responsibilities very seriously: during the 1940s, while based at the Yerkes Observatory, he willingly drove the more than 100-mile trip to the university each week to teach a class of only a few students.

Chandra also had a deep devotion to music, art, and philosophy, writing articles and books about the relationship between the humanities and science. He once wrote that “one can learn science the way one enjoys music or art. . . . Heisenberg had a marvelous phrase ‘shuddering before the beautiful’. . . that is the kind of feeling I have.”

Since a stable white dwarf can no longer contract or produce energy through fusion, its only energy source is the heat represented by the motions of the atomic nuclei in its interior. The light it emits comes from this internal stored heat, which is substantial. Gradually, however, the white dwarf radiates away all its heat into space. After many billions of years, the nuclei will be moving much more slowly, and the white dwarf will no longer shine as shown in Figure 11.16. It will then be a black dwarf—a cold stellar corpse with the mass of a star and the size of a planet. It will be composed mostly of carbon, oxygen, and neon, the products of the most advanced fusion reactions of which the star was capable.

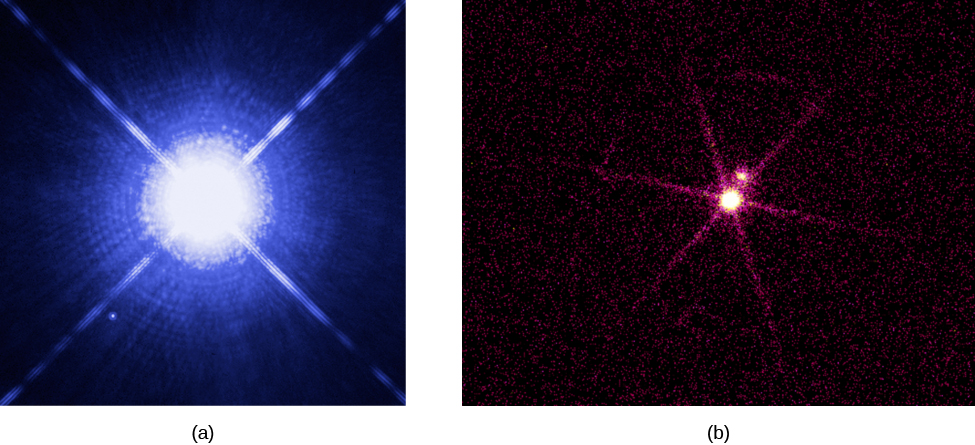

Visible Light and X-Ray Images of the Sirius Star System

The Dog Star, Sirius A, and its tiny companion by NASA, ESA, H. Bond, M. Barstow(University of Leicester), ESA Standard License.

Sirius A and B:A Double Star System In The Constellation Canis Major by NASA/SAO/CXC, NASA Media License.

We have one final surprise as we leave our low-mass star in the stellar graveyard. Calculations show that as a degenerate star cools, the atoms inside it in essence “solidify” into a giant, highly compact lattice (organized rows of atoms, just like in a crystal). When carbon is compressed and crystallized in this way, it becomes a giant diamond-like star. A white dwarf star might make the most impressive engagement present you could ever see, although any attempt to mine the diamond-like material inside would crush an ardent lover instantly!

Attribution

“23.1 The Death of Low-Mass Stars” from Douglas College Astronomy 1105 by Douglas College Department of Physics and Astronomy, is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted. Adapted from Astronomy 2e.