Chapter 8: Pragmatics

8.2 Cross-community differences in discourse

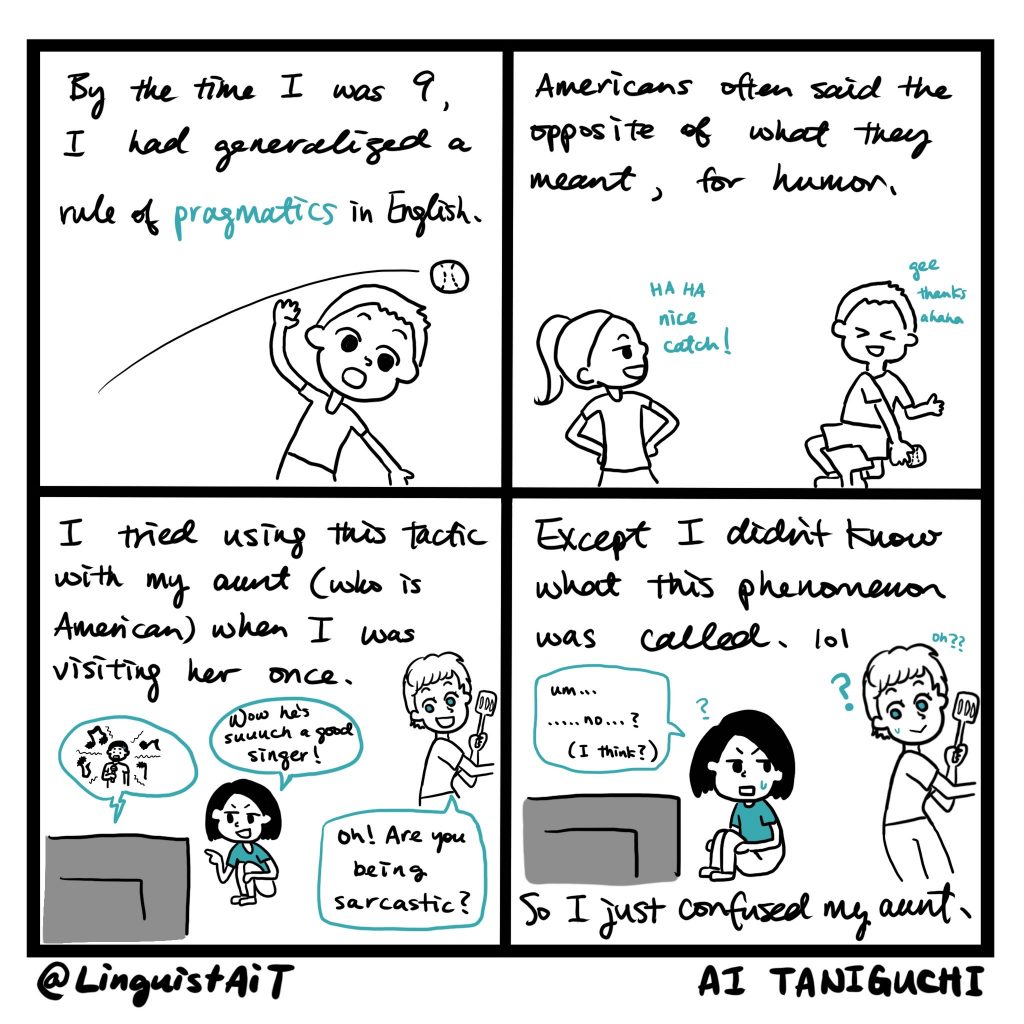

Imagine a time where you were in a conversation with someone with a cultural background different from yours. Have there been times where miscommunication happened? As someone who immigrated to the United States from Japan at the age of 6, I certainly had experiences where American conversational rules felt really different from Japanese conversational rules. One of things I remember learning “how to do” in English is sarcasm (see Figure 8.1). Something I noticed was that Americans (in my 9-year old perspective) said blatantly false things, often to be funny, sassy, or mean. I distinctly recall one summer — I must’ve been 9 or 10 — where we visited a friend in Japan, and in a conversation with this friend, I used this new discourse tactic that I was so proud to have acquired. waa, kore cho: okaidoku-da-ne ‘Wow, that is such a good deal!’ I said in Japanese, pointing at super expensive jewellery in a magazine. I will never forget the confused look on my Japanese friend’s face. Studies support my anecdotal experience: Ziv (1988) found that American students are more sarcastic than Japanese students (see also Adachi 1996).

There are different conversational rules for different language communities. What counts as a ‘friendly’ interaction? What counts as ‘polite’? Linguists who have done anthropological work have found imperatives (commands like “cut down that branch!”) can vary in terms of their perceived politeness from culture to culture: they may be more commonly perceived as rude in Australia than in China, for example (Wierzbicka 2003). In Canadian English, Why don’t you close the window? could be a perfectly polite request, but according to Wierzbicka, the literal equivalent of this in Polish — Dlaczego nie zamkniesz okna — would imply stubbornness on the part of the addressee (e.g., ‘why haven’t you closed the window yet like you should?! it’s the right thing to do!’). In ordinary conversational contexts, being honest is usually assumed to be one of the most important principles of conversation (Grice 1975), but what counts as “being honest” may vary from community to community. In some communities, any falsehood — including fiction — is considered a “lie” (Danziger 2010).

When we study pragmatics, we need to be aware that there are cultures and conversational norms beyond your own. Encountering unfamiliar discourse rules in a language that you may not have encountered before may give rise to feelings of surprise, and that’s OK — but we hope that you will use your linguist mind to prevent this surprise from turning into negative judgments about other cultures and languages. Remember, all forms of language are valid!

Check your understanding

This is a reflection question with no right answer. Have you ever had an experience like the one described in the comic in Figure 8.1, where you had to learn new conversational rules in another language? Informally describe what the unfamiliar rule was, and compare it to conversational rules in your first language.

References

Adachi, T. (1996). Sarcasm in Japanese. Studies in Language. International Journal sponsored by the Foundation “Foundations of Language”, 20(1), 1-36.

Carson, T. L. (2006). The Definition of Lying. Noûs, 40(2), 284–306. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3506133

Danziger, E. (2010). On trying and lying: Cultural configurations of Grice’s Maxim of Quality. , 7(2), 199-219. https://doi.org/10.1515/iprg.2010.010

Grice, H. P. (1975). Logic and conversation. In Speech Acts (pp. 41-58). Brill.

Ziv, A. (1988). Teaching and learning with humor: Experiment and replication. The Journal of Experimental Education, 57(1), 4-15.