Chapter 10: Language Variation and Change

10.8 Sociolinguistic correlations: Gender

Our gender is a social acquisition that comes about through socialization over our lifetime (and sometimes even prior to our start of life… I’m looking at you ‘gender reveal’ parties). Sex on the other hand is something that is assigned to us based on aspects of our (usually external) biology at birth. You’ve probably heard that “gender is the socially-constructed counterpart of biological sex” (Cheshire 2002: 427). That’s only half true though: binary sex is also a social construct (see Eliot 2011 and Fausto-Sterling 2012). Although sex is colloquially spoken about as a biological binary, its anatomical, endocrinal, and chromosomal criteria all exist on continua; the two discrete categories of ‘male’ and ‘female’ are split at a socially-constructed and fuzzy boundary. For cisgender people, their gender identity (i.e., as a man, as a woman, as masculine, as feminine) is (largely) consistent with the sex that they were assigned at birth (i.e., male, female). For transgender people, their gender identity differs from the sex they were assigned at birth and often differs from the gender identity they were socialized into earlier in life. For nonbinary and genderqueer people, their gender identity does not (always) map to the spectra of masculinities and femininities. In cultures across the world, gender is not restricted to a binary (e.g., two-spirit people in some Indigenous communities in North America and hijras in India).

Understanding the distinction between gender and sex is important because past variationist sociolinguistic research often collapsed the difference. As Eckert (1989: 246–7) observed over 30 years ago: “Although differences in patterns of [linguistic] variation between men and women are a function of gender and only indirectly a function of sex …, we have been examining the interaction between gender and variation by correlating variables with sex rather than gender differences.” Eckert’s main point here is that although variationists frequently talk about two groups based on ‘sex differences’, the linguistic difference between men and women is not a biological fact but a social one: men do not use certain variants in a certain way because of their particular anatomy, hormones, and chromosomes but because they have been socialized into using language ‘like a man’. In the early years of the field, little attention was paid to the complexity of gender and the normative binary was taken for granted. Moreover, participants in earlier variationist work were typically categorized based on their gender presentation (i.e., how the researcher perceived the participant’s gender) rather than their self-identification.

The complexity of gender helps to explain well-observed gendered-patterns of variation. These patterns have been found over and over again in so many studies that Labov (2001) codified them as principles of linguistic change. (There is one, pretty big, caveat here though: the vast majority of the studies where the pattern has been found represent languages embedded in Euro-American culture!)

- Principle I: In stable variation, women use more of the standardized variant than men do.

- Principle Ia: In changes from above, women favour the incoming prestige variant more than men.

- Principle II: In changes from below, women are most often the innovators.

Principles I and Ia are named as such because they similarly involve women using more of the overtly prestigious variant. An example of Principle I in action can be seen in Figure 10.5 from Wolfram’s (1969) study of th-stopping in Black English in Detroit. This is a stable variable that involves the variable realization of /θ/ as [θ] or [t] in words like think [θɪŋk~tɪŋk] and with [ʍɪθ~ʍɪt]. Figure 10.5 shows the frequency of the non-standard [t] variant of variable th-stopping among men and women across four different social classes. Critically, even in the face of social stratification, men have a higher rate of the non-standard variant [t] than women who favour the standard form [θ].

![Graph showing social class on x-axis with four levels (upper middle, lower middle, upper working, and lower working). Y-axis shows percentage of [t] variant. Two different coloured lines represent an independent variable of gender with two levels: men and women. Both lines gradually increase from Upper Middle to Lower Working and the line representing men is always higher than the line representing women.](https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/sites/1310/2022/02/GenderSplit-e1645824290321.png)

One proposed explanation for Principles I and Ia appeals to (Euro-American) gender ideologies (in interaction with social class). Eckert and McConnell-Ginet (2013: 253) identify two character tropes on the extremes of the gender binary that serve as imaginary reference points in the performance of femininity and masculinity. You can think of these as extreme stereotypes of the ‘ideal’ woman and ‘ideal’ man; no real woman or real man exists who fit these stereotypes, but their characteristics serve as a baseline for expressions of normative femininity and masculinity. First is the girlie-girl: “her body is small, delicate, she moves gracefully, she smells faintly of delicate flowers, her skin is soft, she is carefully groomed from hair to toenails. She dresses in delicate fabrics, she smiles, she is polite, and she speaks a prestige variety. Wealth refinement is central to canonical femininity”. Think early-era Taylor Swift. On the other end of the binary is the manly-man: “grounded in the physical – in size and strength, in heavy and dirty work, in roughness, toughness, and earthiness. The stereotypical man is working class.” Think Born in the U.S.A.-era Bruce Springsteen. In general, these are the gender ideals against which men and women are evaluated, socialized into, and often consciously and unconsciously conform to. But what is feminine about prestige language? For one, as we saw above, people in higher social classes use more standard variants and wealth refinement is a central aspect of canonical femininity. Moreover, Deuchar (1989) suggests that standard language can protect “the face of a relatively powerless speaker without attacking that of the addressee”. In the context of patriarchal male dominance, standard speech functions, in some ways, as a survival strategy.

At the same time, further expectations are put on women’s language. In one of the most influential papers on the sociocultural study of language and gender, Robin Lakoff defined the double bind: women are socialized not just to use standard language but powerless and tentative language… to talk ‘like a lady’. But, in Lakoff’s (1972: 48) words, “a girl is damned if she does, damned if she doesn’t.” Her tentative, powerless language will be seen as a reflection on her (in)ability to participate in serious discussion but if she resists and subverts this expectation, she runs the risk of being deemed unfeminine.

In a study based in Norwich England, Peter Trudgill (1972) compared people’s actual frequency of use of standard and non-standard variants with those people’s own perceptions of how standard or non-standard they thought their speech was. The majority of women in the study over-reported their use of the standard. Trudgill concluded that women are more linguistically standard because they are more status-conscious than men. But it would be an error to assume that only women are linguistically status-conscious, the only ones adjusting their language in reaction to these norms and ideas of standardness. Men too are status-conscious but in reaction to canonical masculinity. Most of the men that Trudgill interviewed believed they were more non-standard than they actually were! Men of all social classes and backgrounds make use of non-prestigious working class language and white men often adopt features of non-prestigious Black language in the name of covert prestige. The use of these linguistic forms indexes the toughness and physical dominance that class and racial ideologies assign to working class and Black men – characteristics of the canonical masculinity that is desirable to all men.

So an appeal to gender, class, and racial ideologies offers an explanation for Principles I and Ia: that women tend to use more standard variants and men tend to use less in stable variation and in changes from above. But Principles I and Ia contrast with Principle II, which essentially notes that women deviate from the standard (i.e., they innovate away from the current norm) more than men when no one is looking! Labov (2001: 293) calls this the gender paradox: “women conform more closely than men to sociolinguistic norms that are overtly prescribed, but conform less than men when they are not”. The complexity of gender again offers explanation. The gender paradox is true only in the aggregate: only when we collapse all men and all women together does the pattern emerges. But it is not categorically true: there are women who deviate more from the standard than some men, and vice versa.

Penelope Eckert demonstrated this idea in her groundbreaking work on linguistic variation among adolescents in a suburban Detroit-area high school (see Eckert 1989, 2000). Like just about every high school across North America, this high school had two major cliques. First, were the ‘jocks’. The jocks included the athletes of the school, as you might imagine, but the group was a bit broader. They included the students who were involved in all school-oriented activities: sports, band, academic societies, and school council. Jocks generally express overt respect for the hierarchical system of the school and the authority of their teachers and principals. The other group, the ‘burnouts’, were anti-school and their interests fell outside of school (things like sex, drugs and rock ‘n’ roll!). The ‘burnouts’ were also overtly anti-authority. These two groups can be understood as two different communities of practice: groups that share common interests, concerns, and goals. While the jocks embody middle class ideals and the burnouts embody working class ideals, a student’s social class and community of practice did not always align. That is, there were working class jocks and middle class burnouts.

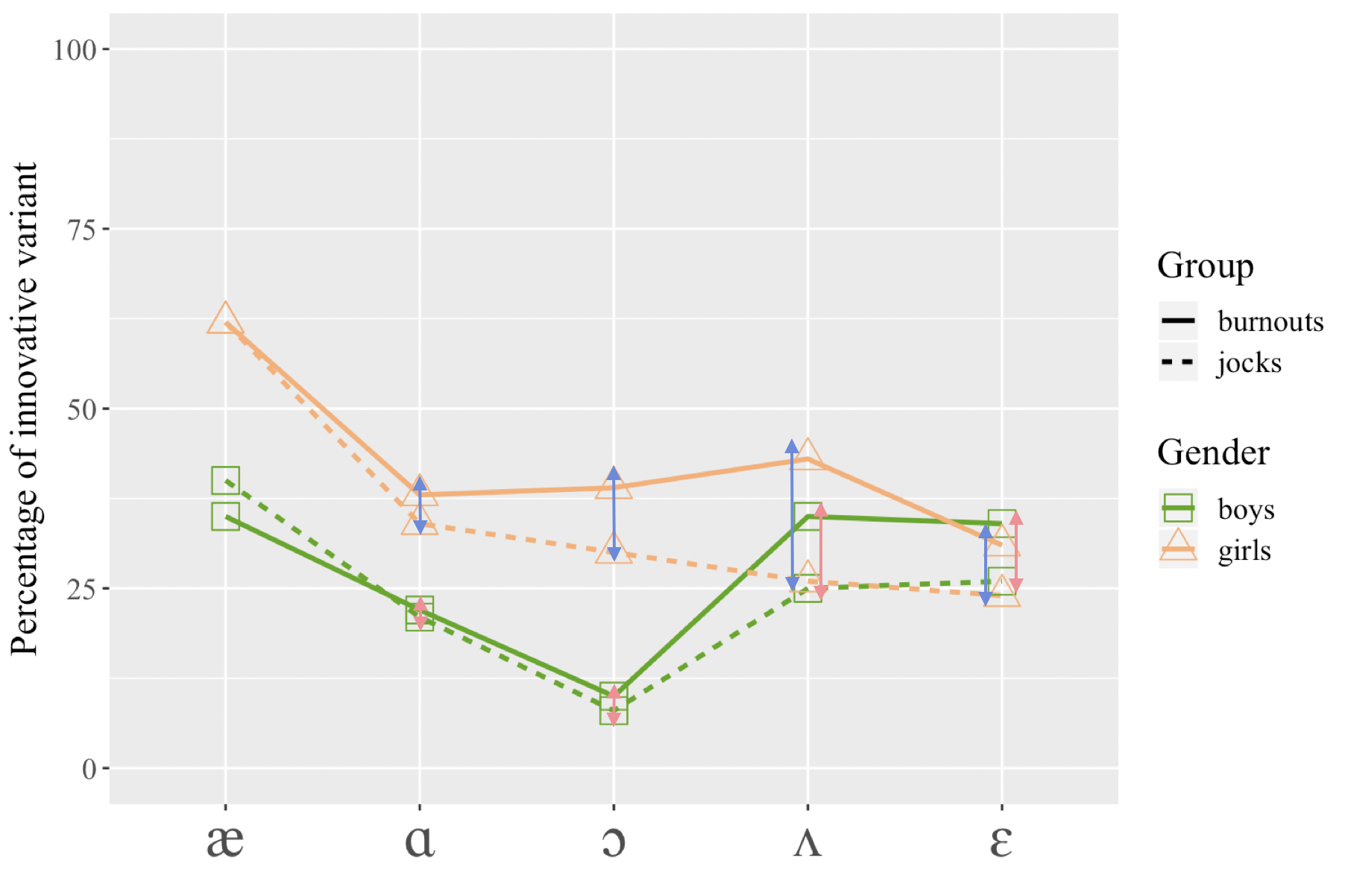

Regardless of group, the boys in Eckert’s study expressed their group identity through their actions, like being on the football team for the jocks or, for the burnouts, ‘cruising’ (getting in a car and driving in and around downtown Detroit, maybe getting out and going to a bar or a rock concert). Girls on the other hand relied on projecting an image to express their identity. Jock girls must be friendly, outgoing, all-American, clean cut, and preppy, while burnout girls need to be tough, urban, and ‘experienced’ (that is, sexually active). This plays out linguistically as well as can be seen when we look at the patterns of variation in the school around the five variables of the Northern Cities Chain Shift.

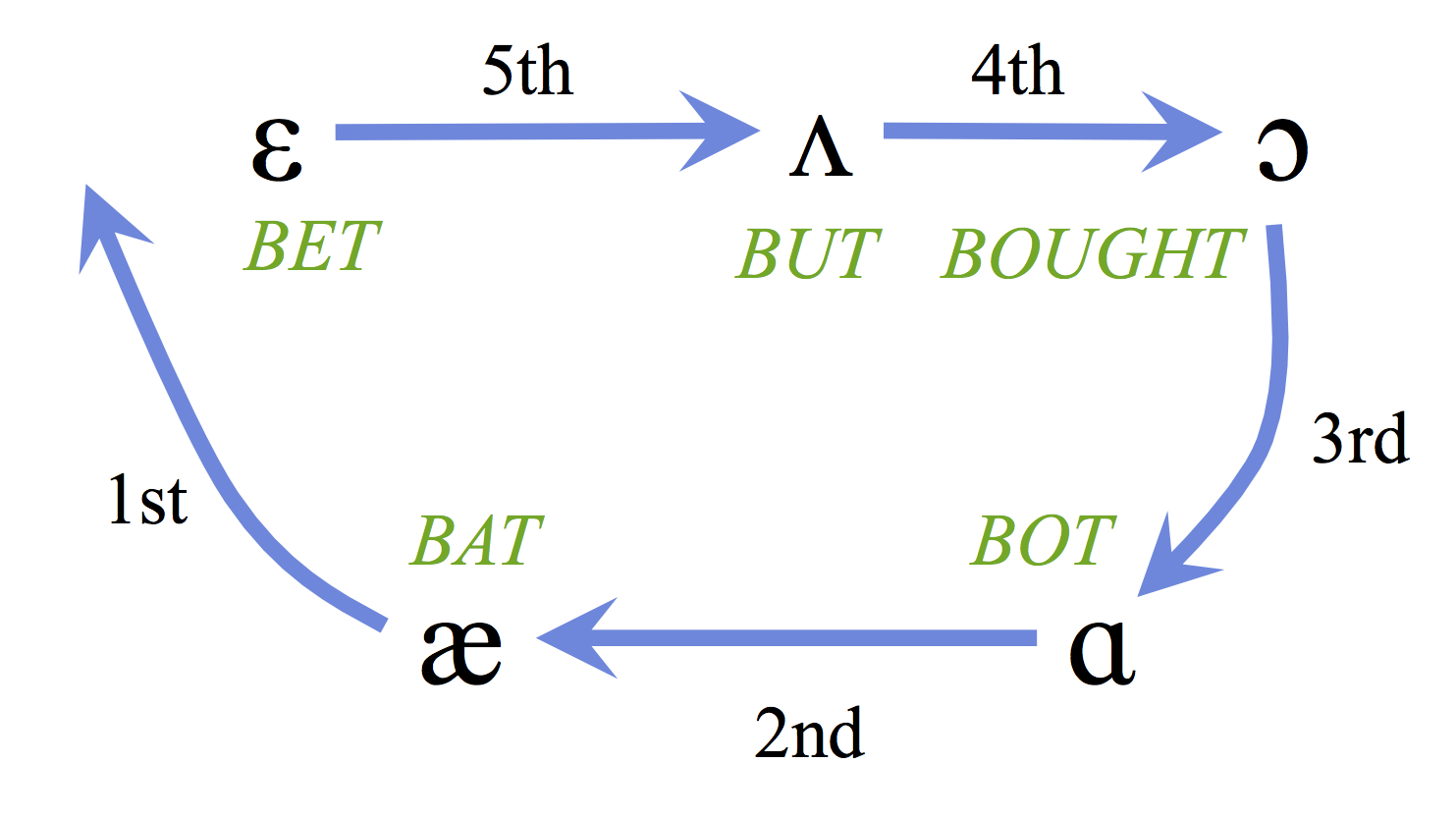

Chain shifts. Chain shifts are a kind of change that affects several linguistic features in a systematic and serial way. A common kind of chain shift is a vowel chain shift, like the Northern Cities Chain Shift. The idea is that once one vowel starts to move away from its older position, other vowels are pushed or pulled around the vowel space to accommodate: just like when you pull at one link of a chain, all the subsequent links move too. The Northern Cities Chain Shift, found in urban areas across New York state, Michigan, Illinois, and elsewhere, involves a change in both the height and backness of five vowels. The vowel in BAT [æ] moves higher, so it sounds more like [ɛ]; the vowel in BOT [ɑ] shifts forward and is pronounced more like [æ]; the vowel as in BOUGHT [ɔ] lowers to sound more like [ɑ] (note though that in Canadian English, these two vowels have merged); the vowel in BUT [ʌ] moves back and sounds more like [ɔ] and the vowel in BET [ɛ] moves back and sounds more like [ʌ]. Each of these changes triggers the next one, so there is a chronological order to the changes. BAT started to move first, followed by BOT, then BOUGHT, then BUT, and most recently BET began to move, as you can see in Figure 10.6.

Figure 10.7 plots the frequency of the innovative variant of each of the five changes associated with the Northern Cities Chain Shift as used by four groups in the high school: burnout boys, burnout girls, jock boys, and jock girls. The five variables are arranged along the x-axis from oldest [æ] to newest [ɛ]. With the older changes, the gender of the speaker is a better predictor of variation than community of practice; but with the newer changes, it’s community of practice that’s most important with the burnouts on the forefront of innovation and the jocks lagging behind (regardless of gender). What you can also see in this chart, as indicated by the arrows, is that for all variables except the oldest, the difference between community of practice is much larger for the girls (blue arrows) than the boys (pink arrows).

And here’s the solution to the gender paradox: ‘women’ (and ‘men’) are not a cohesive, homogenous group! It’s the subset of “non-conformist” women (like the burnout girls here) who are the leaders of changes from below. The difference between men and women, on aggregate, is not about status consciousness, but the fact that women are more status bound. While men’s status depends on their accomplishments, possessions, and institutional status (i.e., what they do/have), women are evaluated on their symbolic capital (i.e., who they are/appear to be). Both men and women accumulate symbolic capital, but it is “the only kind that women can accumulate with impunity” (Eckert 1989: 256). The upshot is there is a wider range of linguistic differentiation (reflecting social category distinctions) among women than among men. Women “maintain more rigid social boundaries, since the threat of being associated with the wrong kind of person is far greater to the individual whose status depends on who she appears to be rather than what she does” (Eckert 1989: 258).

You’ll notice that this section has said nothing about the language use of transgender, nonbinary, and gender diverse people. For decades the linguistic practices of transgender, nonbinary, and gender diverse people were either ignored or studied only because they subverted exceptions of previous theories of language and gender (Konnelly 2021). Most, if not all, of this research was also conducted by cisgender linguists. However, over the last decade or so, transgender and nonbinary linguists have begun to study language within their own communities and from a far more affirming perspective (Zimman 2020). Some of this work has shown how linguistic variation can be used as a means of constructing a nonbinary identity. Gratton (2016) looks at the the use of variable -ing by two Canadian English speaking nonbinary people in two different contexts: one, a safe queer space and the other, an unfamiliar, non-queer space. Gratton finds that in the safe, queer context both speakers use each of the two variants around 50% of the time. However, in the non-queer spaces where they express legitimate fear of being misgendered, the two speakers diverge sharply from each other. One speaker, in reacting to the threat of being misgendered as a woman, used a very high rate of the masculine-associated [ɪn] variant, while the other speaker, reacting to the threat of being misgendered as a man, used a very high rate of the feminine-associated [ɪŋ]. Gratton (2016: 56) argues that it’s not the case that these two speakers are attempting to align with cis-masculinity or cis-femininity respectively – they are both non-binary! – but rather, they “utilize resources that they associate with cis-normative masculinity [and femininity] … in order to distance [themselves] enough from cis-normative femininity [or masculinity respectively] that they [are] not misgendered as such.” In this way, both linguistic variation provides both speakers a means of “perform a non-binary identity” (Gratton 2016: 57).

References

Cheshire, J. (2002). Sex and Gender in Variationist Research. In J.K. Chambers, P. Trudgill, & N. Schilling-Estes (eds.)The handbook of language variation and change. Blackwell. pp. 423–443.

Eckert, P. (1989). The whole woman: Sex and gender differences in variation. Language variation and change, 1(3), 245-267. https://doi.org/10.1017/S095439450000017X

Eckert, P. (2000). Language variation as social practice: The linguistic construction of identity in Belten High. Wiley-Blackwell.

Eckert, P., & McConnell-Ginet, S. (2013). Language and gender. Cambridge University Press.

Eliot, L. (2011). The trouble with sex differences. Neuron, 72(6), 895-898. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2011.12.001

Deuchar, M. (1989). A pragmatic account of women’s use of standard speech. In J. Coats and D. Cameron (eds.) Women in Their Speech Communities. Longman. pp. 27–32.

Fausto-Sterling, A. (2012). Sex/gender: Biology in a social world. Routledge.

Gratton, C. (2016). Resisting the Gender Binary: The Use of (ING) in the Construction of Non-binary Transgender Identities. University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics: 22(2): Article 7. https://repository.upenn.edu/pwpl/vol22/iss2/7

Konnelly, L. (2021). Nuance and normativity in trans linguistic research. Journal of Language and Sexuality, 10(1), 71-82. https://doi.org/10.1075/jls.00016.kon

Labov, W. (2001). Principles of linguistic change Volume 2: Social factors. Blackwell.

Lakoff, R. (1973). Language and woman’s place. Language in society, 2(1), 45-79. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047404500000051

Sachs, J. , Lieberman P. & Erickson, D. (1973). Anatomical and cultural determinants of male and female speech. In R.W. Shuy and R.W. Fasold (eds.) Language Attitudes: Current Trends and Prospects. Georgetown University Press.

Trudgill, P. (1972). Sex, covert prestige and linguistic change in the urban British English of Norwich. Language in society, 1(2), 179-195. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047404500000488

Wolfram, W. (1969). A Sociolinguistic Description of Detroit Black Speech. Center for Applied Linguistics.

Zimman, L. (2020). Transgender language, transgender moment: Toward a trans linguistics. In K. Hall and R. Barrett (eds.) The Oxford Handbook of Language and Sexuality. Oxford University Press. pp. 1-23.