Chapter 3: Phonetics

3.3 Describing consonants: Place and phonation

Consonants as constrictions

Consonants are phones that are created with relatively narrow constrictions somewhere in the vocal tract. These constrictions are usually made by moving at least one part of the vocal tract towards another, so that they are touching or very close together. The moving part is called the active or lower articulator, and its target is called the passive or upper articulator. Vowels have wider openings than consonants, so they are not usually described with the terms used here; more appropriate terminology for vowel articulation is discussed in Section 3.5.

Active articulators

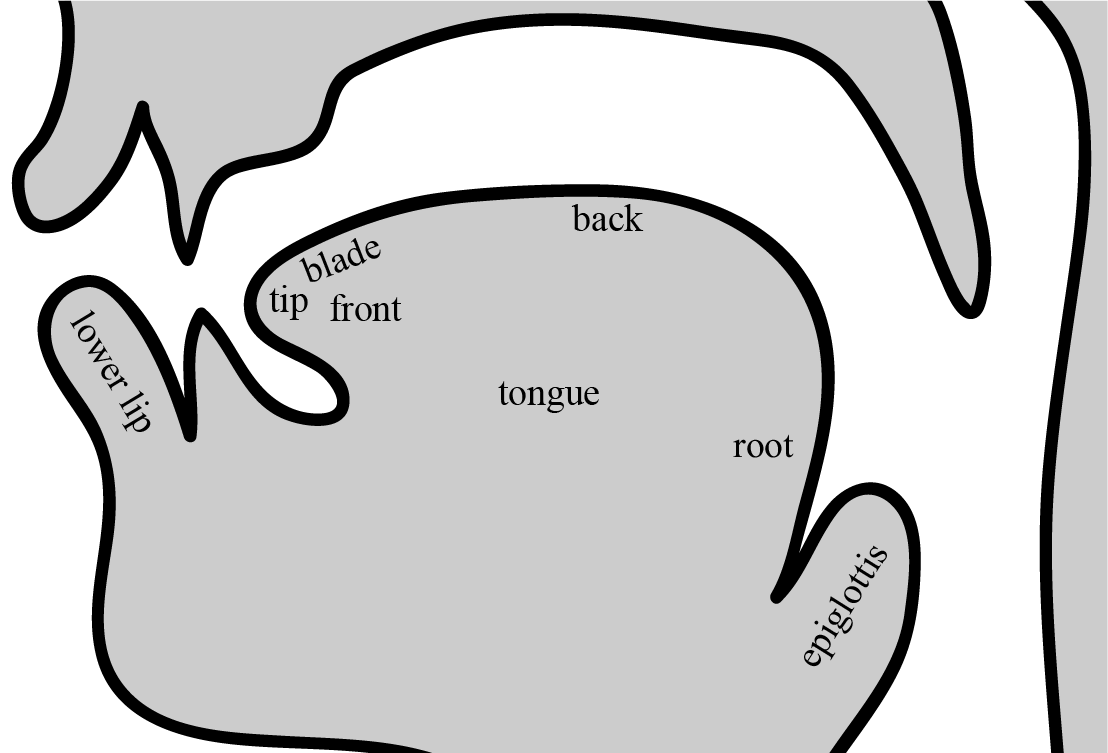

The active articulators we find in phones across the world’s spoken languages are listed below, in order from front to back. They are also labelled in the midsagittal diagram in Figure 3.3.

- the lower lip, which is used for the consonants at the beginning of the English words pin and fin

- the tongue tip (the frontest part of the tongue; also called the apex), which is used for the consonants at the beginning of the English words tin and sin

- the tongue blade (the region just behind the tongue tip; also called the lamina), which is used for the consonants at the beginning of the English words thin and chin

- the tongue front (the tip and blade together as a unit, also called the corona); it is useful to have a unified term for the tip and blade together, since they are so small and so close, and languages, and even individual speakers of the same language, may vary in which articulator is used for similar phones; for example, while many English speakers use the tongue tip for the consonant at the beginning of the word tin, other speakers may use the tongue blade or even the entire tongue front; however, while there may be variation in some languages, the distinction between the tip and blade is crucial in others, such as Basque (a language isolate spoken in Spain and France), which distinguishes the words su ‘fire’ and zu ‘you’, both of which sound roughly like the English word sue, with the tongue tip used for su and the tongue blade used for zu (although this distinction has been lost for some speakers under influence from Spanish; Hualde 2010)

- the tongue back (the upper portion of the tongue, excluding the front; also called the dorsum), which is used for the consonants at the beginning of the English words kin and gone

- the tongue root (the lower portion of the tongue in the pharynx; also called the radix), which is not used for consonants in English but is used for consonants in some languages, such as Nuu-chah-nulth (a.k.a. Nootka, an endangered language of the Wakashan family, spoken in British Columbia; Kim 2003)

- the epiglottis (the large flap at the bottom of the pharynx that can cover the trachea to block food from entering the lungs, forcing it to go into the esophagus instead), which is not used for consonants in English but is used in for consonants in some languages, such as Alutor (a Chukotkan language of the Chukotko-Kamchatkan, spoken in Russia; Sylak-Glassman 2014)

Note that while the lower teeth could theoretically be an active articulator (we can move them towards the upper lip, for example), it turns out that no known spoken language uses them for this purpose, so we do not include them here.

Each of the active articulators has a corresponding adjective to describe phones with that active articulator. These adjectives are given in the list below, again from front to back:

- labial (articulated with the lower lip)

- apical (articulated with the tongue tip)

- laminal (articulated with the tongue blade)

- coronal (articulated with the tongue front)

- dorsal (articulated with the tongue back)

- radical (articulated with the tongue root)

- epiglottal (articulated with the epiglottis)

Thus, we could say that the English words pin and fin begin with labial consonants, while thin and chin begin with laminal consonants. Note that all apical and laminal consonants are also coronal, so thin and chin can also be said to begin with coronal consonants.

Passive articulators

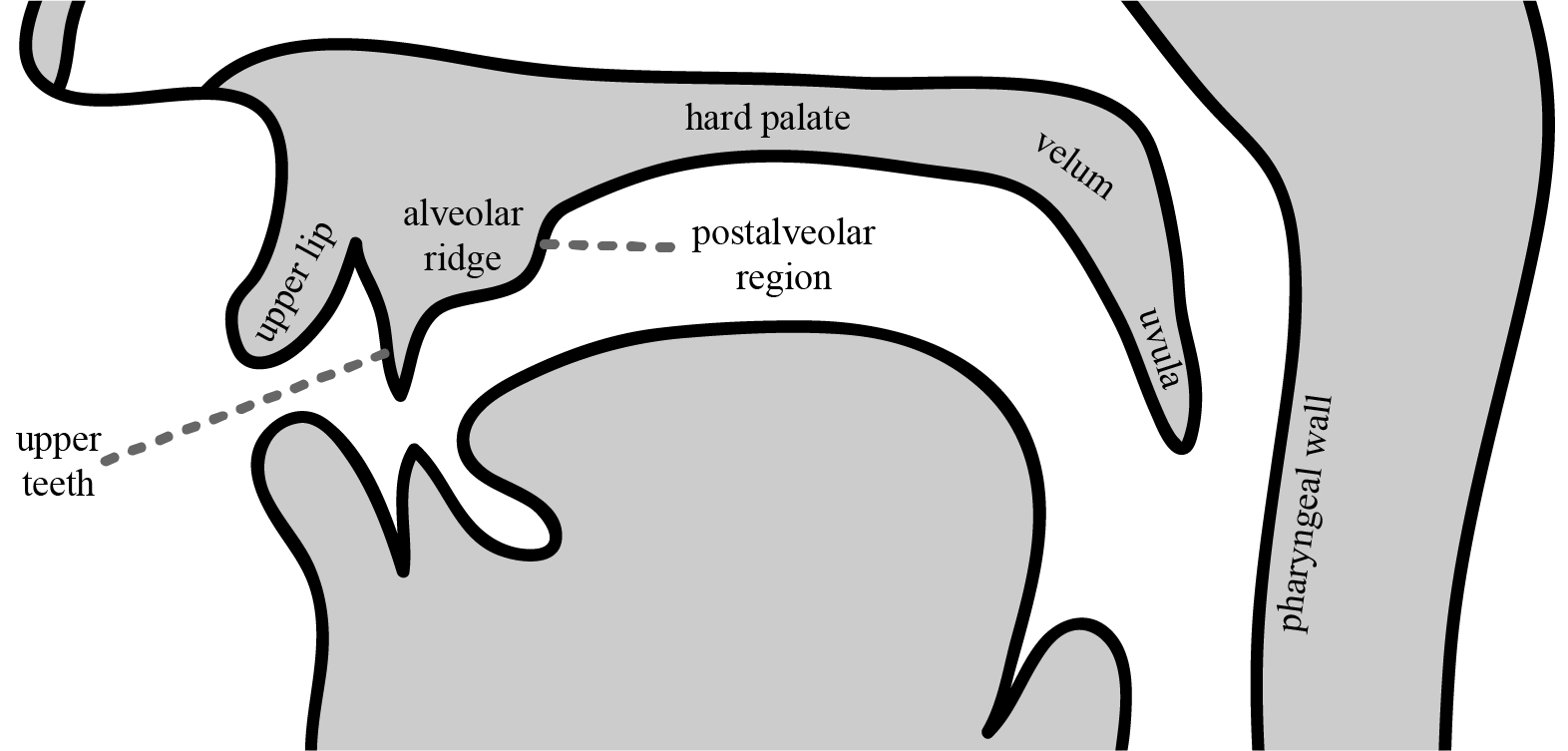

The passive articulators we find in phones across the world’s spoken languages are listed below, in order from front to back. They are also labelled in the midsagittal diagram in Figure 3.4.

- the upper lip, which is used for the consonants at the beginning of the English words pin and bin

- the upper teeth, which are used for the consonants at the beginning of the English words fin and thin

- the alveolar ridge (the firm part of the gums that extends just behind the upper teeth, recognizable as the part of the mouth that often gets burned from eating hot food), which is used for the consonants at the beginning of the English words tin and sin (though some speakers may use the upper teeth instead or in addition)

- the postalveolar region (the back wall of the alveolar ridge), which is used for the consonants at the beginning of the English words shin and chin

- the hard palate (the hard part of the roof of the mouth; sometimes called the palate for short), which is used for the consonant at the beginning of the English word yawn

- the velum (the softer part of the roof of the mouth; also called the soft palate), which is used for the consonants at the beginning of the English words kin and gone

- the uvula (the fleshy blob that hangs down from the velum), which is not used for consonants in English but is used for consonants in some languages, such as Uspanteko (an endangered Greater Quichean language of the Mayan family, spoken in Guatemala; Bennett et al. 2022)

- the pharyngeal wall (the back wall of the pharynx), which is not used for consonants in English but is used in languages that have consonants with the tongue root or epiglottis as an active articulator (such as Nuu-chah-nulth and Archi mentioned earlier)

Each of the passive articulators has a corresponding adjective to describe phones with that passive articulator. These adjectives are given in the list below, again from front to back:

- labial (articulated at the upper lip)

- dental (articulated at the upper teeth)

- alveolar (articulated at the alveolar ridge)

- postalveolar (articulated at the back wall of the alveolar ridge)

- palatal (articulated at the palate)

- velar (articulated at the velum)

- uvular (articulated at the uvula)

- pharyngeal (articulated at the pharyngeal wall)

Thus, we could say that the English words tin and sin begin with alveolar consonants, while kin and gone begin with velar consonants.

Since all consonants have two articulators, they could be described by either of the two relevant adjectives. For example, the consonant at the beginning of the English word shin could be described as a laminal consonant (because of its active articulator) as well as a postalveolar consonant (because of its passive articulator).

Note that the term labial is ambiguous in whether it refers to the lower or upper lip. In general, this ambiguity is not a problem, so labial consonants include those with the lower lip as an active articulator as well as those with the upper lip as a passive articulator.

Place of articulation

The overall combination of an active articulator and a passive articulator is called a consonant’s place of articulation, or simply place for short. Places of articulation are usually described with a compound adjective that refers to both articulators, with the adjective for the active articulator first (without the –al ending), then a linking –o-, followed by the adjective for the passive articulator.

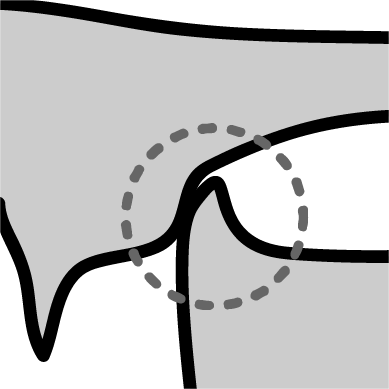

For example, the consonant at the beginning of the English word fin is a labiodental consonant, because it is articulated with the lower lip (labi-) at the upper teeth (-dental), as circled in the midsagittal diagram in Figure 3.5a. Similarly, the consonant at the beginning of the English word kin is dorsovelar, because it is articulated with the tongue back (dors-) at the velum (-velar), as circled in the midsagittal diagram in Figure 3.5b.

|

|

Not all combinations of active and passive articulators are used in the world’s spoken languages. Some are simply impossible. For example, ordinary humans cannot stretch their lower lip to reach all the way back to the pharyngeal wall, so there is no such thing as a labiopharyngeal consonant.

Other combinations are physically possible, but no spoken language is known to use them. For example, most people have little difficulty touching their tongue tip to the velum, but that articulation is awkward enough that no language seems to have apicovelar consonants. Of course, our knowledge of language is constantly expanding, so we could theoretically come across apicovelar consonants in some language someday, but it is unlikely.

Many of the places of articulation are used frequently enough that their corresponding compound adjectives are normally replaced with a shorter adjective, often highlighting just the passive articulator. For example, apicoalveolar (tongue tip and alveolar ridge) is often shortened to just alveolar, because the tongue tip is more commonly used than the tongue blade when the alveolar ridge is the passive articulator. The full adjective can be used as needed to distinguish apicoalveolar from laminoalveolar (tongue blade and alveolar ridge), such as when a language has both kinds of alveolar consonants, as with Basque mentioned earlier.

Other shortened adjectives are used because one of the articulators is predictable from the other. For example, dorsovelar is often shortened to just velar, because no other active articulator is ever used with the velum as a passive articulator.

Other common shortened adjectives for places of articulation are listed below:

- laminodental (tongue blade and upper teeth) ⇒ dental

- dorsopalatal (tongue back and hard palate) ⇒ palatal

- dorsouvular (tongue back and uvula) ⇒ uvular

- radicopharyngeal (tongue root and pharyngeal wall) ⇒ pharyngeal

- epiglottopharyngeal (epiglottis and pharyngeal wall) ⇒ epiglottal

Note that palatal phones move the entire upper part of the tongue, both the front and the back, so they technically count as both coronal and dorsal. However, the tongue back is often considered the more important active articulator, and it is often the only active articulator listed for palatals.

Some other alternative adjectives are used in certain special cases. For example, consonants that use both lips as articulators, such as the consonants at the beginning of the English words pin and bin, are called bilabial rather than the inelegant term labiolabial. Note that for bilabial phones, both lips are involved roughly equally, with each actively moving towards the other as mutual targets. So for the bilabial place of articulation, it is technically more accurate to say that the lips are the lower and upper articulators, but it is common to refer to the lower lip at the active articulator and the upper lip as the passive articulator.

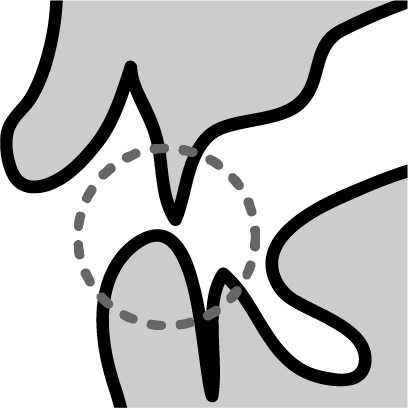

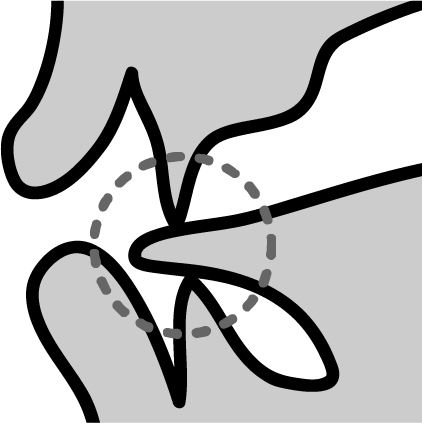

Another special case are dental consonants. There are two main types. In the most common case, the tongue blade is on or near the back of the teeth (as circled in Figure 3.6a). In the other main type, the tongue protrudes between the two sets of teeth, with the tongue blade below the bottom edge of the upper teeth (as circled in Figure 3.6b). The first type of dental consonant is what is often referred to by default as dental (as a shortening for laminodental), while the second type is called interdental. The consonants at the beginning of the English words thin and then are commonly articulated as interdental.

|

|

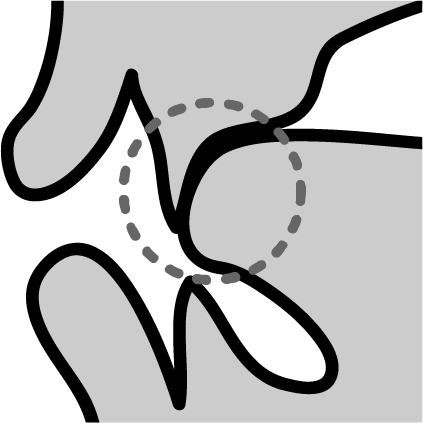

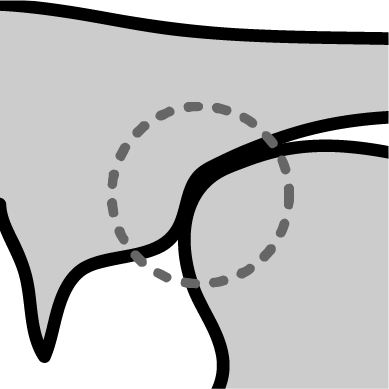

Finally, there are also two main types of postalveolars. In the most common case, the tongue blade is on or near the alveolar ridge (as circled in Figure 3.7a). In the other case, the tongue tip curls backward, so that the tip points towards the hard palate, and the underside of the tongue tip is at or near the back wall of the alveolar ridge (as circled in Figure 3.7b). The first type of postalveolar consonant is what is often referred to by default as postalveolar, while the second type is called retroflex. The consonant at the beginning of the English word run is articulated as retroflex by some speakers, but there is much variation.

|

|

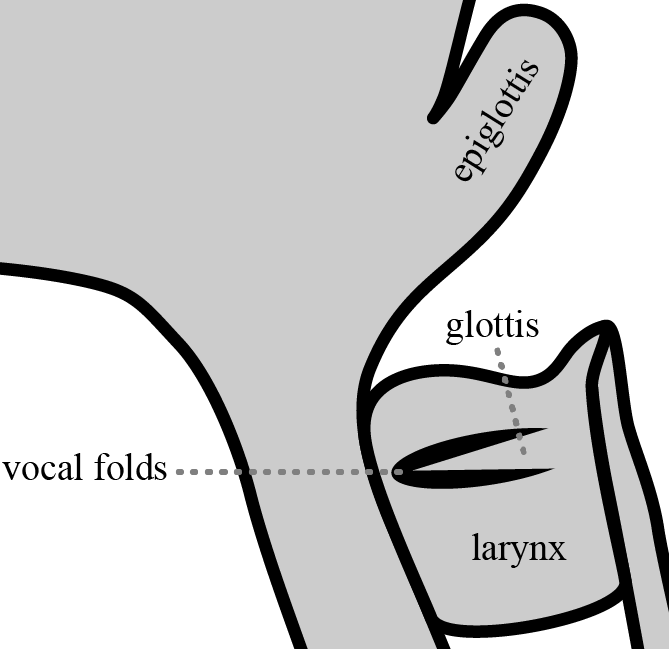

Glottal articulation

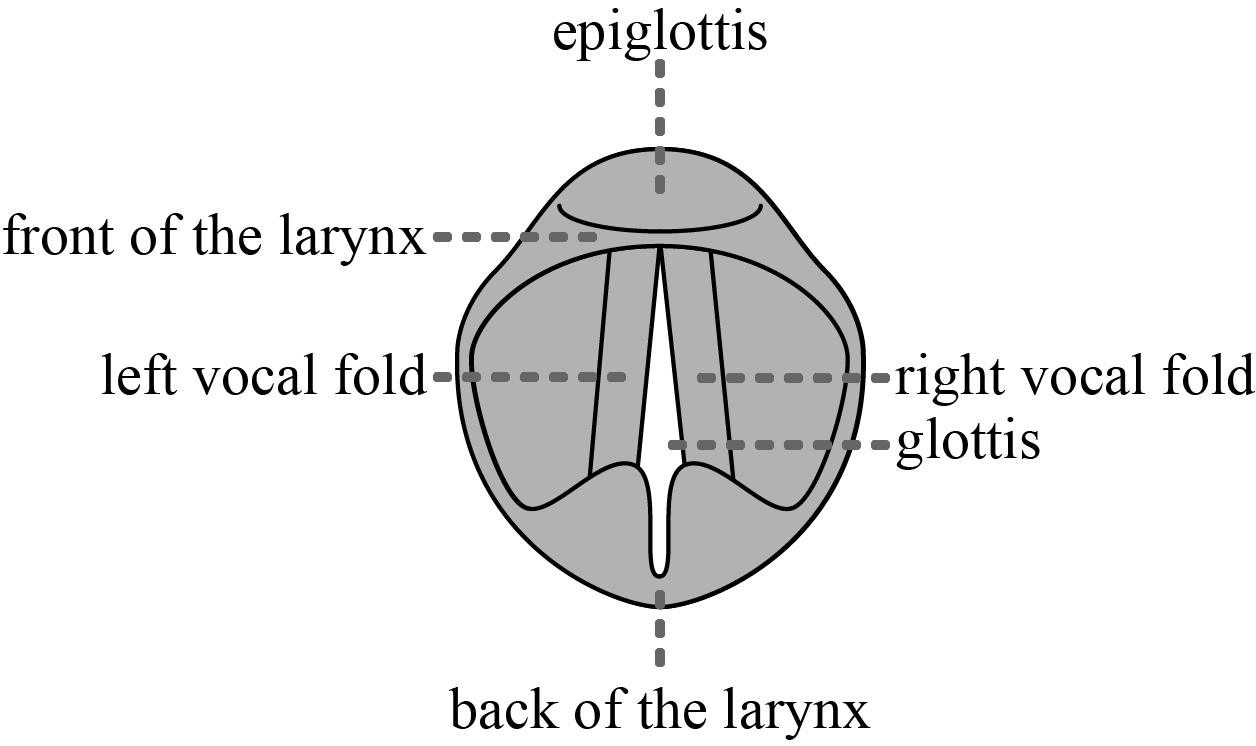

There is one important place of articulation that is somewhat different from the ones discussed so far. At the top of the trachea is the larynx (or voice box), a rigid combination of cartilages that surround the trachea. Inside the larynx are the vocal folds (or vocal cords), which are two membranes that stretch from front to back. The vocal folds are separated by an empty space, the glottis. These structures are shown from the side in the midsagittal diagram in Figure 3.8a and in more detail as viewed looking down the throat in Figure 3.8b.

|

|

Some consonant phones seem to consist only of articulation of the vocal folds, with no significant movement of any of the active articulators discussed previously. We see this with the first consonant in the English words he and who. Such phones are said to have a glottal or laryngeal place of articulation. Unlike other consonants, they have no clear active or passive articulator (since both vocal folds move equally) and no clear lower or upper articulator (since the vocal folds are at the same height).

Additionally, across the world’s spoken languages, we find that glottal consonants behave somewhat oddly, sometimes acting more like vowels than consonants. Because of this, glottal consonants are sometimes said to have no inherent place of articulation of their own. Instead, they seem to pick up aspects of the articulation of the phones around them, especially vowels. You should be able to observe this in the first consonant of the English words he and who, especially in the configuration of the lips. The lips are spread into a smile throughout he, but they are rounded throughout who (see Section 3.5 for more information about lip configuration and other vowel properties). So even though we may think of these two words as starting with the same consonant, they are articulated in different ways, at least at the lips. But importantly, they have the same glottal articulation.

Regardless of the problematic nature of the glottal place of articulation, it is still typically counted among the possible places of articulation for consonants, and we follow that practice here. A full table of the places of articulation discussed in this chapter is given in Table 3.1, showing the usual shortened adjective, plus the active and passive articulators (with none given for glottal, since neither of the vocal folds has a privileged status over the other).

| place of articulation | active articulator | passive articulator |

| bilabial | lower lip | upper lip |

| labiodental | lower lip | upper teeth |

| dental / interdental | tongue blade | upper teeth |

| alveolar | tongue tip | alveolar ridge |

| postalveolar | tongue blade | postalveolar region |

| retroflex | underside of the tongue tip | postalveolar region |

| palatal | tongue front and back | hard palate |

| velar | tongue back | velum |

| uvular | tongue back | uvula |

| pharyngeal | tongue root | pharyngeal wall |

| epiglottal | epiglottis | pharyngeal wall |

| glottal | — | — |

In addition to acting as a place of articulation for some consonants in some languages, the vocal folds are also used to regulate airflow through the vocal tract for most consonants and vowels in all spoken languages. In particular, when the vocal folds are configured in the right way, airflow through the glottis will cause the vocal folds to vibrate.

You can feel this vibration by placing your fingers on the front of your throat where the larynx is, while making the sound of a bee buzzing, like the sound of the consonant at the end of the English word buzz. If instead you make the sound of a snake hissing, like the sound of the consonant at the end of the English word bus, you should feel that there is no vocal fold vibration. Switch between buzzing and hissing to feel the change in the presence versus absence of vibration: zzzzz-sssss-zzzzz-sssss-zzzzz-sssss.

Vocal fold vibration is often called voicing, and a phone with vocal fold vibration is called voiced, while a phone without it is called voiceless or unvoiced. There are many other ways the vocal folds can play a role in shaping airflow. This larger category of manipulating airflow with the vocal folds in different ways is called phonation; you may sometimes see the term voicing refer to phonation generally, but this should be avoided, so that voicing can refer specifically to phonation in which the vocal folds vibrate. In this textbook, we will only discuss voiced and voiceless phonation.

Check your understanding

References

Bennett, Ryan, Meg Harvey, Robert Henderson, Tomás Alberto, and Méndez López. 2022. The phonetics and phonology of Uspanteko (Mayan). Language and Linguistics Compass 16(9): e12467.

Hualde, J. Ignacio. Neutralización de sibilantes vascas y seseo en castellano. Oihenart 25: 89–116.

Kim, Eun-Sook. 2003. Theoretical issues in Nuu-chah-nulth phonology and morphology. Doctoral dissertation, University of British Columbia, Vancouver.

Sylak-Glassman, John. 2014. Deriving natural classes: The phonology and typology of post-velar consonants. Doctoral dissertation, University of California, Berkeley.