Chapter 7: Semantics

7.11 Denotation

Sense vs. denotation

So far in this chapter, we have spent a lot of time on lexical meaning: the meaning of words and other linguistic expressions you store in your mental lexicon. In doing so, we have been analysing meaning in term of the sense of the linguistic expressions. The sense of a word is what that word expresses; you store the sense of listemes in your mental lexicon.

Figuring out the sense of any given word is a difficult task. Let’s take a look at a summary of what we have been able to figure out about word senses so far.

- It’s probably not just a list of necessary and sufficient conditions;

- It’s probably tied to concepts in some way;

- Verbs (and other predicates) specify how many arguments it takes, and what role these arguments play;

- Nouns specify whether it’s count (bounded) or mass (unbounded);

- Adjectives specify whether it’s stage-level (bounded) or individual-level (unbounded);

- Some adjectives have a degree argument, some do not.

What we’ve done is identify some major patterns in word senses, but this of course doesn’t fully answer the question “what do words mean?”. If we ask right now what the sense of the adjective sour was, our best approximation would be ‘x is sour to degree d ‘. You may still be wondering, “but what does it mean for something to be sour, exactly, though?”. Similarly, we know that the lexical semantics of pencil says that it’s a count noun, but what makes a pencil a pencil?

Some linguists have proposed that word meaning encodes things like what parts it has (e.g., a pencil is something consists of graphite or a similar substance), what its purpose is (e.g., a pencil is something that is used for writing), and how it came into being (e.g., pencils are man-made, not found in nature) (Pustejovsky 1995). Much of this is still on-going research in linguistics.

Although words like pencil have a somewhat articulable meaning, there are other words like sour whose sense is actually quite hard to characterise, except that it’s, well… that sour taste. What about the word care? What does it actually mean for someone to care about something? What’s the different between a jacket and a coat? Are hotdogs sandwiches? If we focused on the sense of a specific word, we could write a whole book on it! Sense is fun to think about, but if we focus too much on a single word, we can lose sight of the bigger picture. Generally, lexical semanticists are not interested in “pinning down” the exact meaning of any particular word. Instead, they ask more general questions like: “What lexical meaning patterns do we see across different words?”, “What semantic classes of nouns, verbs, and adjectives are there?”, “What is the nature of lexical meaning in the lexicon?”, “How is lexical meaning represented in our minds?”, “How are lexical entries organised in our lexicon?”, and “How does lexical meaning relate to cognition?”.

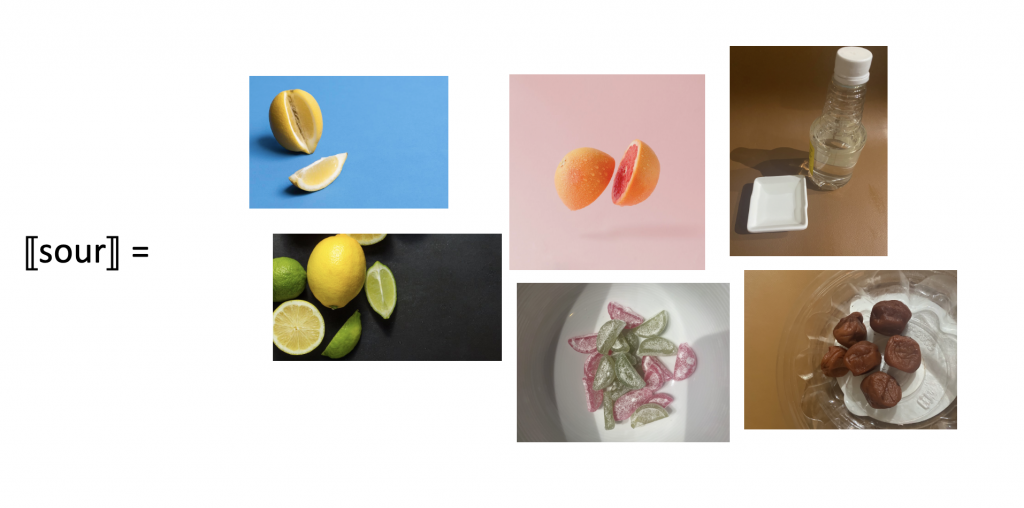

There is another angle of analysing linguistic meaning: denotation. If you were really pressed by someone to say what the meaning of sour was, you might eventually grab a lemon and say, “Look, this is sour, OK! It’s whatever this is!”. This is a way to talk about the meaning of the word sour via denotation. The denotation of a linguistic expression is what that linguistic expression points to in the actual world. Sour points to all sour things in the world, including lemons, limes, grapefruit, vinegar, pickles, etc. The denotation of pencil would be the set of all things that are pencils in the actual world.

More about denotation

We just said that denotation is what the linguistic expression points to in the actual world, but it’s actually slightly more complicated than that. When we say that the denotation of a word is what it points to in the actual world, we run into problems when we want to analyse the meaning of words like unicorn, or names like Mario (the character from the Nintendo games). If denotations were what these words points to the actual world, then that would be nothing (what mathematicians call the empty set) — because unicorns and Mario do not actually exist in the real world. That means if we take word meaning to be denotations, then unicorn and Mario would be meaningless. But we don’t want to say that! Surely, they are meaningful still. So more accurately, denotation is what the linguistic expression points to in our cognitive representation of the actual world. So words point to the abstract representation of the world that we have in our cognitive faculty, and not the actual things out there, so to speak. Fictional things can certainly have a representation in our cognition, so if we think of denotation this way, even words like unicorn and Mario have “things” they point to in our cognitive faculty. For simplicity, we will say “in the actual world” when discussing denotations in this textbook, but keep in mind that technically, it’s the cognitive representation of the actual world in our minds.

Denotation and sense are related, which is why it is useful to talk about both. Sense is what you store in your head as the semantic information of that word. And whatever this internal information is, that‘s the knowledge that allows you to point to things out there in the real world and say, yes, that’s sour, no, that’s not sour, etc. So the two modes of meaning are connected in that the sense of a word is what you use to figure out the denotation of that word. So even without knowing the exact sense of a word, we can still get a lot of insight about how meaning works in language.

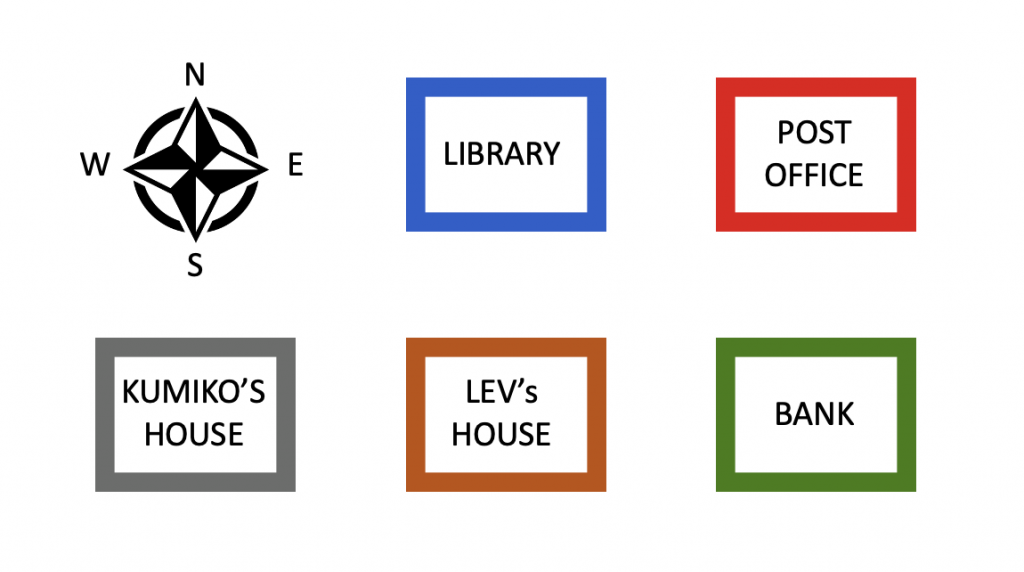

To understand the difference between sense and denotation, consider the following map. Let’s say that this map represents an actual town in Ontario.

Let’s say that you are explaining to someone where the post office is in this town. There are several ways to describe its location, including (1) and (2).

| (1) | The building to the north of the bank | |

| (2) | The building to the east of the library |

The phrases in (1) and (2) have different senses: the phrases don’t contain identical words (e.g., north vs. east, bank vs. library), so the internal semantic content of each phrase would be different. However, (1) and (2) have the same denotation: the post office in this town. Although described differently, both phrases point to the same thing.

Consider also an expression like (3).

| (3) | My house |

Imagine that Kumiko said (3). If that were the case, the expression in (3) would point to Kumiko’s house in this town (represented by the bottom left box on the map). If Lev said it though, this same expression would point to Lev’s house (represented by the bottom middle box on the map). This means that my house has a different denotation depending on who says it. It has the same sense no matter who says it though: something along the lines of ‘the place of living that is associated with the speaker’.

The denotation of words

Denotation gives us a fairly efficient way to talk about the meaning of words. For sour, you are essentially saying, “sour is whatever property that all of these sour things have in common.” You are pointing to that group of sour things. So, we can characterise the denotation of one-place predicates (predicates that only take one argument: some nouns, adjectives, and intransitive verbs) as sets of things. A set is a collection of things. In (4), ⟦x⟧ (x enclosed in double brackets) should be read as ‘the denotation of the linguistic expression x ‘.

| (4) | a. | ⟦sour⟧ = the set of all sour things in the actual world |

| b. | ⟦pencil⟧ = the set of all pencils in the actual world | |

| c. | ⟦snore⟧ = the set of all things that snore in the actual world |

You might find it unintuitive that verbs denote a set of individuals too. But think about it this way: if someone asked “Who snores?”, you can answer “they do” and point to the people that have this snoring property.

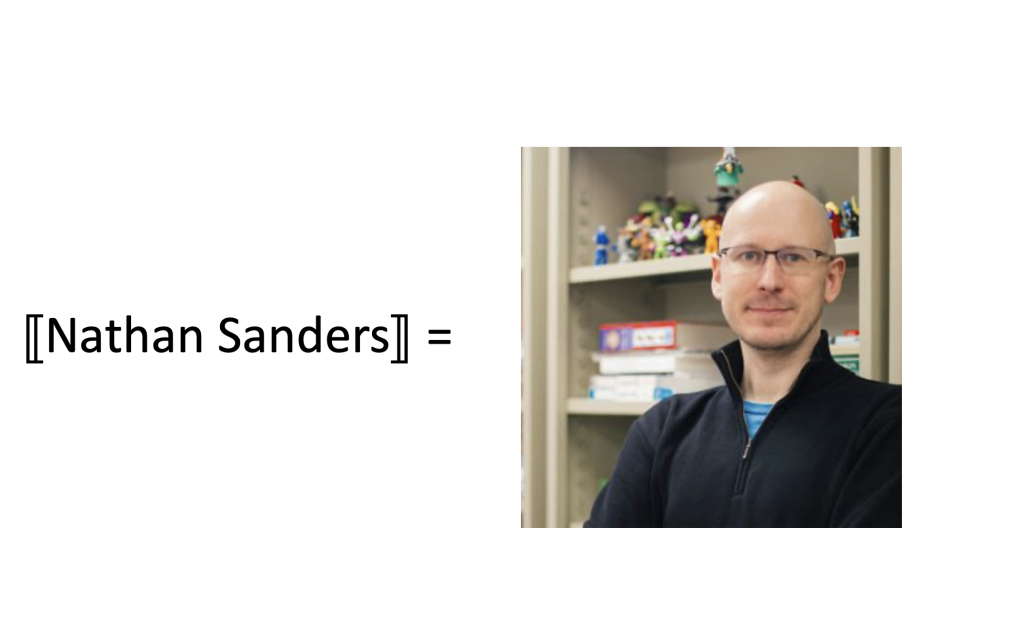

We will treat the denotation of proper names (like Nathan Sanders, the name of a linguist, who happens to be one of the co-authors of this textbook) to be the particular individual that that the name is pointing to in that context. In other words, the denotation of Nathan Sanders is the individual Nathan Sanders in the actual world. Sometimes the denotation of a name is abbreviated as the initial letter of the name (and bolded), like in (5b).

| (5) | a. | ⟦Nathan Sanders⟧ = the individual Nathan Sanders in the actual world |

| b. | ⟦Nathan Sanders⟧ = n |

Constants and variables

The symbol that stands for the denotation of Nathan Sanders (in this case the bolded lowercase n) is called a constant. A constant is different from a variable. Recall that a variable is a placeholder for other values; it’s called a variable because what it stands for can vary. A constant has a fixed value: what it stands for cannot be altered. So in (5), the constant n always stands for the individual Nathan Sanders. Any letter or symbol can be used as constants or variables, although traditionally, letters towards the beginning of the alphabet in English are typically used for constants (e.g., a, b, c) and letters towards the end of the alphabet tend to be used for variables (e.g., x, y, z). In this textbook, constants will be bolded, but variables won’t be.

When a linguistic expression denotes (points to) a unique individual, this can also be called the expression’s reference. For example, a name like Nathan Sanders points to a unique individual, so the individual Nathan Sanders is this name’s reference. We can also say that the name Nathan Sanders refers to that individual.

It should be re-emphasized here that words like sour, pencil, snore, and Justin Trudeau denote actual things in the actual world. When we say “⟦sour⟧ = the set of all sour things in the actual world,” we are not saying that the denotation of the word sour is the phrase (the linguistic expression) the set of all sour things in the actual world. We are quite literally saying that the word sour points to actual sour things that exist out there in the real world (or at least, our cognitive representation of them; see note above). The following representation may be helpful for imagining what denotation really is:

Because we don’t always have the time to find stock images to represent the denotation of a linguistic expression, in this textbook, we will use the convention in (4) and (5).

Thinking of meaning in terms of the linguistic expression’s denotation is useful in various ways. For example, how can we characterise the compositional meaning of the sentence Nathan Sanders snores? The denotation of snore(s) is the set of all things that snore in the actual world, and the denotation of Nathan Sanders is the individual Nathan Sanders in the actual world. What Nathan Sanders snores means, then, is that this individual Nathan Sanders is among this set of things that snore in the actual world.

The denotation of sentences

We know what some words denote now; how about sentences? What do they denote? One property of a sentence is that it has a truth value. There are two truth values in language: the abstract truth value true (sometimes written as T or 1), or the abstract truth value false (sometimes written as F or 0). To say that a sentence has a truth value means that a sentence is always either true or false. Words and non-sentential phrases don’t have truth values. You can see if a linguistic expression has a truth value or not by embedding it in the construction “It is true/false that…”, like in (6).

| (6) | a. | It is true/false that Nathan Sanders snores. | |

| b. | * | It is true/false that Nathan Sanders. | |

| c. | * | It is true/false that snores. | |

| d. | * | It is true/false that lives in Canada. | |

| e | * | It is true/false that in Canada. | |

(6) shows that only sentences have truth values. Taking this observation, we can actually think of the denotation of sentences as its truth value: either the value T or the value F. In other words, sentences “point to” these abstract truth values. (7a) shows the denotation of a sentence that is true, and (7b) shows the denotation of a sentence that is false.

| (7) | a. | ⟦Nathan Sanders is bald⟧ = T | |

| b. | ⟦Nathan Sanders is not bald⟧ = F |

It is crucial to observe here that you need world knowledge in order for you to determine the denotation of a sentence. Oftentimes, we know enough about the world that we know whether a sentence is true or false (like the above examples). However, the more realistic view is that we don’t know everything about every single thing in the world. Take the sentence My neighbour’s cat’s liver weighs 326 grams for example: what’s the denotation of this sentence? It it true or false? The sentence surely has a truth value, but we don’t have the relevant world knowledge to actually determine the truth value. This is why we often express the denotation of a sentence as its truth condition (the circumstances that yield a certain truth value). The truth condition of My neighbour’s cat’s liver weighs 326 grams is shown in (8).

| (8) | ⟦My neighbour’s cat’s liver weighs 326 grams⟧ = | T if my neighbour’s cat’s liver weighs 326 grams in the actual world, F otherwise |

It might help to think of it this way: if we really wanted to, we could figure out if the sentence in (8) is true or false. Whether we can or want to is another matter. What’s more relevant is that we know what circumstances would make the sentence true or false.

If and only if

The denotation in (8) can also be written as “T if and only if my neighbour’s cat’s liver weighs 326 grams in the actual world”. If and only if means ‘provided that’: T provided that my neighbour’s cat’s liver weighs 326 grams in the actual world. This means that if my neighbour’s cat’s liver weighs 326 grams, then the truth value is T, and that if the truth value is T, then my neighbour’s cat’s liver weighs 326 grams. So, “if and only if” (sometimes also abbreviated as “iff“) means that the implication goes both ways. This is the same thing as what (8) says.

The formula for the denotation of a sentence should be seen as: truth condition + world knowledge = truth value. If we reframe (7) in terms of truth conditions, we get something like this:

| (9) | a. | ⟦Nathan Sanders is bald⟧ = T if Nathan Sanders is bald, F otherwise | |

| b. | ⟦Nathan Sanders is not bald⟧ = T if Nathan Sanders is not bald, F otherwise |

In this case, we can combine our world knowledge with each truth condition to get T in (9a) and F in (9b), which is what was shown in (7). If you do have the relevant world knowledge to determine the truth value of a sentence, you should write out the actual truth value, like in (7). If you don’t have the relevant world knowledge, you can write the denotation of the sentence as a truth condition.

In summary, intransitive verbs, adjectives, and nouns denote sets, proper names denote an individual, and declarative sentences denote truth values. In the rest of this chapter, we will look at various semantic phenomena that denotative meaning is equipped to explain.

Check your understanding

References

Frege, G. (1892). Über sinn und bedeutung. Zeitschrift für Philosophie und philosophische Kritik, 100, 25-50.

Pustejovsky, J. (1995). The Generative Lexicon. MIT Press.