Chapter 3: Phonetics

3.6 The International Phonetic Alphabet

Segmentation

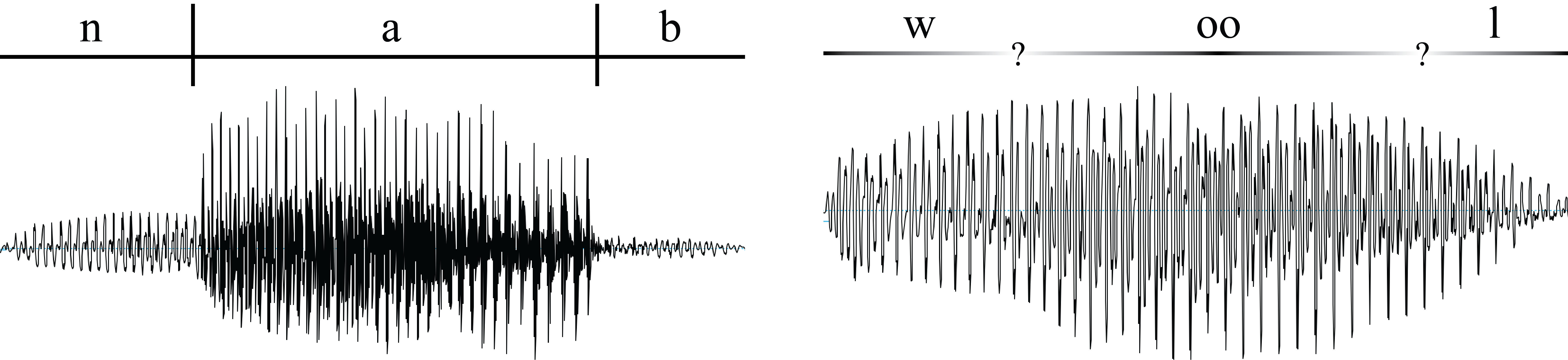

Note that we have been talking about phones as if it were obvious what they are, but this is not always the case. It is sometimes easy to find a clear separation between the phones in a given word, that is, to segment the word into its component phones, but sometimes, it can be very difficult. We can see this difference by looking at waveforms, which are special pictures that graphically represent the air vibrations of sound waves. The two waveforms in Figure 3.19 show a notable difference in how easy it is to segment the English words nab and wool.

The waveform for nab contains abrupt transitions between three very different regions, corresponding to three phones. In comparison, the waveform for wool has smooth transitions from beginning to end, with no obvious divisions between phones. For the purposes of this textbook, all words will be segmented for you, but it is important to remember that when working with raw data from a spoken language, it may not be so clear where the boundaries are between phones.

Transcription

When we can identify the individual phones in a word, we want to have a suitable way to notate them that can be easily and consistently understood, so that the relevant information about the pronunciation can be conveyed in an unambiguous way to other linguists. Such notation is called a transcription, which may be very broad (giving only the minimal information needed to contrast one word with another), or it may be very narrow (giving a large amount of fine-grained phonetic detail), or somewhere in between. Whether broad, narrow, or in between, phonetic transcription is conventionally given in square brackets [ ], so that, for example, the consonant at the beginning of the English word nab could be transcribed as [n], with the understanding that the symbol [n] is intended to represent a voiced alveolar nasal stop.

As linguists, we are interested in studying and describing as many languages as we can, so for spoken languages, we ideally want to use a transcription system that can be used for all possible phones in any spoken language. This means we cannot simply use one existing language’s writing system, because it would be optimized for representing the phones of that language and would not have easy ways to represent phones from other languages.

In addition, many writing systems are filled with inconsistencies and irregularities that make them unsuitable for any kind of rigorous and unambiguous transcription, even for their associated spoken language. For example, the letter <a> in the English writing system is used to represent different phones, such as the low front unrounded vowel in nab, the low back unrounded vowel in father, the mid front tense unrounded vowel in halo, and the mid central unrounded vowel in diva. Conversely, the high front unrounded tense vowel in English can be represented by different letters and letter combinations: <i> in diva, <ee> in meet, <ea> in meat, <e> in me, and <y> in mummy. That is, then English writing system does not have a one-to-one relationship between phones and letters.

Furthermore, even if English spelling were perfectly regular, many specific English words have different equally valid pronunciations, such as either, data, and route. But even words that seem to have only one consistent pronunciation may in fact be pronounced differently by different speakers in more subtle ways. For example, in Los Angeles and London, the vowel in the word mop normally has a low back tongue position, with the London vowel also having some lip rounding that is not used in the Los Angeles pronunciation. In Chicago, the vowel in mop is articulated more in the centre of the mouth, making mop sound nearly like map to other speakers. If we tried to describe in writing how to pronounce a vowel from another language, and we said that it was pronounced the same as the vowel in the English word mop, we could not guarantee that the reader would know whether the vowel in question is back and unrounded (as in Los Angeles mop), back and round (as in London mop), or central and unrounded (as in Chicago mop).

The International Phonetic Alphabet

To avoid these problems, linguists have devised more suitable transcription systems for spoken languages, each with their own strengths and weaknesses. In this textbook, we will use a widespread standard transcription system called the International Phonetic Alphabet (abbreviated IPA). The IPA was created by the International Phonetic Association (unhelpfully also abbreviated IPA). The IPA organization was founded in 1886, and the first version of their transcription system was published shortly after. Since then, the IPA transcription system has undergone many revisions as our understanding of the world’s spoken languages has evolved. The most recent symbol was added to the IPA in 2005: [ⱱ] for the labiodental tap, a phone found in many languages of central Africa, such as Mono (a Central Banda language of the Ubangian family, spoken in the Democratic Republic of the Congo; Olson and Hajek 1999).

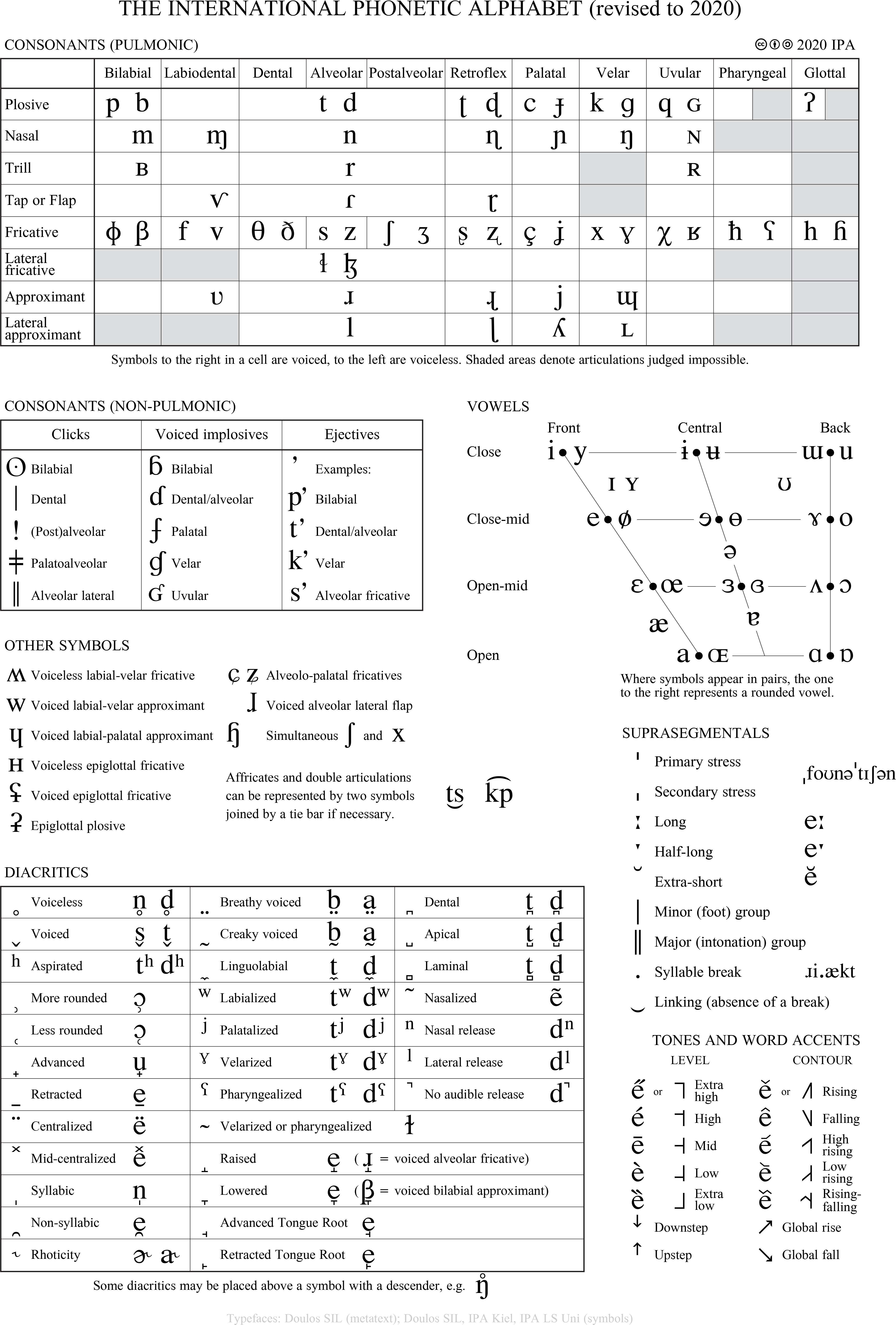

For reference, the full chart for the IPA is given in Figure 3.20. This chart is available under a Creative Commons Attribution-Sharealike 3.0 Unported License, copyright © 2020 by the International Phonetic Association. It is also available online at the IPA’s homepage, and there are also some online versions that are accessible for screenreaders, such as this one created by Weston Ruter.

Learning the IPA takes a lot of time, practice, and guidance, and it is not just about memorizing symbols. The underlying structure and principles behind the organization of the table are what really matter. In this way, the IPA is like the periodic table of elements in chemistry. So, while it is helpful to know that Na is the chemical symbol for the element sodium with atomic number 11 and that [m] is the IPA symbol for a voiced bilabial nasal stop, it is much more important to know what these concepts are and what those terms mean. What is sodium? What does it mean for an element to have an atomic number of 11? What does it mean for a phone to be voiced? How is the vocal tract configured for a bilabial nasal stop?

This is why this chapter focuses on defining concepts, so that you can build a solid foundation in understanding how phones are articulated. The notation is also important, but it has no value without the corresponding conceptual understanding.

Using the IPA

A full discussion of how to use the IPA for transcription is beyond the scope of an introductory textbook like this one. Here, we discuss a few guidelines and some concrete examples from English. For any transcription, it is important to keep in mind who your audience is and what the purpose of the transcription is. Most of the time, we normally only need a fairly broad transcription to get across a basic idea of the most important aspects of the articulation.

One important guiding recommendation from the IPA for broad transcription is to use the typographically simplest notation that still conveys the most crucial information. For example, when possible, we should choose symbols like upright [a] and [r] rather than their rotated counterparts [ɐ] and [ɹ]. These upright symbols are easier to type, easier to read, and more reliable in how they are displayed in different fonts.

Another aspect of typographic simplicity is to avoid diacritics, which are special marks like [ ̪ ] and [ʰ] that are placed above, below, through, or next to a symbol to give it a slightly different meaning. These are often necessary for certain contexts, but sometimes, they are superfluous and can hinder the reader’s understanding. Thus, you should use diacritics when their meaning is crucial, but avoid them otherwise.

Typographic simplicity is also good practice when dealing with a lot of variation between speakers that is not relevant to the main point. For example, the English consonant typically spelled by the letter <r> is pronounced in many different ways by different speakers, sometimes even differently by the same speaker (DeLattre and Freeman 1968). Many North Americans have some sort of central approximant, but it varies from alveolar [ɹ], to postalveolar [ɹ̱], to retroflex [ɻ]. In addition to the primary place of articulation, some speakers may also have secondary pharyngealization, with a constriction between the tongue root and pharyngeal wall, which is indicated in the IPA with a [ˁ] diacritic after the symbol. Some speakers may have some amount secondary lip rounding, which is indicated in the IPA with a [ʷ] diacritic after the symbol. Some speakers may have both pharyngealization and rounding!

That results in at least twelve different possible articulations, each with its own transcription in the IPA, depending on the place of articulation, whether or not there is pharyngealization, and whether or not there is lip rounding. The IPA symbols for these twelve possibilities are given in the list below. For each, the symbols are in order by place of articulation: alveolar, postalveolar, and retroflex.

- no pharyngealization and no rounding: [ɹ], [ɹ̱], or [ɻ]

- pharyngealization and no rounding: [ɹˁ], [ɹ̱ˁ], or [ɻˁ]

- rounding and no pharyngealization: [ɹʷ], [ɹ̱ʷ], or [ɻʷ]

- both pharyngealization and rounding: [ɹˁʷ], [ɹ̱ˁʷ], or [ɻˁʷ]

Furthermore, there are many other rhotic pronunciations beyond those in North American varieties, such as an alveolar tap [ɾ] or trill [r] in Scotland (Johnston 1997), a voiced uvular fricative [ʁ] in Northumbria (Maguire 2017), and a labiodental approximant [ʋ] in southeast England (Foulkes and Docherty 2000).

Thus, when transcribing English in general, there is no one single symbol that accurately represents the pronunciation of this consonant, so for broad transcription, a plain upright [r] with no diacritics is a reasonable choice that follows the IPA’s recommendation for typographic simplicity. Of course, when transcribing a specific articulation from a specific speaker, it may make sense to use a more precise symbol, especially if the details of the articulation are important. But generally speaking, a plain upright [r] is normally fine for English, though some linguists may prefer to use [ɹ] or [ɻ] for North American English, even though there are at least a dozen equally valid North American pronunciations. If you are taking a course in linguistics, be sure to follow the standards and conventions set by your instructor.

Even when the pronunciation of a given phone is fairly consistent across speakers, many linguists still choose a typographically simpler transcription. Consider the consonant at the beginning of the English word chin, which is a voiceless postalveolar affricate. Affricates in the IPA are normally transcribed by writing the corresponding plosive symbol to represent the stop closure, followed by the corresponding fricative symbol to represent the fricated release, both united under a curved tie-bar [ ͡ ] to show they are unified as a single phone.

So, to represent the voiceless postalveolar affricate in chin, we need to select the correct plosive and fricative symbols. First, let us consider the voiceless postalveolar fricative. We can find its symbol in the IPA chart by looking in the section devoted to consonants. Places of articulation are listed across the top, while manners of articulation are listed down the left. Within a given cell, if there are two symbols, the one on the left is voiceless, and the one on the right is voiced. So looking in the postalveolar column and the fricative row, we find the symbols [ʃ] and [ʒ], and since we are interested in the voiceless fricative, we pick the symbol [ʃ].

However, there is no similar basic symbol for a voiceless postalveolar plosive in the IPA. That part of the chart is blank, so we have to create our own symbol by using the base symbol for a similar consonant and adding one or more diacritics. In this case, we can use alveolar [t] and put a retraction diacritic [ ̱ ] under it to indicate that its place of articulation is slightly farther back, as we did for the postalveolar central approximant [ɹ̱] before. Thus, we get [ṯ] as the symbol for a voiceless postalveolar plosive.

So, we would begin by putting these two symbols together under a tie-bar: [ṯ͡ʃ]. However, most English speakers also pronounce this affricate with some amount of lip rounding, so a fully accurate transcription would be something more like [ṯ͡ʃʷ], with the [ʷ] diacritic to indicate rounding.

But hardly any linguist transcribes this affricate with that much phonetic detail. It is almost never relevant to indicate that it is round, and the postalveolar location of the stop closure is implied by the fact that it has a postalveolar release. You cannot release a stop closure in a position different from where it is made: if there is a postalveolar release, it necessarily must come from a postalveolar closure. So for typographic simplicity, the affricate is more commonly transcribed simply as [t͡ʃ], with neither of the two diacritics. As with [r] for the English rhotic, [t͡ʃ] is not technically an accurate transcription for most speakers, but it is typographically simpler and conveys of all the crucial information needed to understand the basics of the articulation. The tie-bar on the affricate may also sometimes be left off in transcriptions, so [tʃ] is also a common transcription for this affricate, making it even more typographically simple.

Even without these issues, there is still usually no such thing as “the” correct transcription of a word. Two pronunciations of the same word by the same speaker will always have some differences, because we live in a physical world where we cannot avoid slight imperfections and fluctuations. Even if we wanted to capture all of those possible differences with the IPA, it is simply not designed for that level of phonetic detail. When such detail is important, it needs to be conveyed in other ways, such as with pictures (like waveforms and midsagittal diagrams) and numerical measurements (like loudness in decibels and duration in milliseconds). Thus, an IPA transcription is always inherently missing some details, so we have to decide how much detail is needed and how much should be left out for simplicity.

Transcribing English with the IPA

Despite all these pitfalls, it is still important to get some basic skill in transcription for future work in linguistics. Since this textbook is presented in English, English is a good starting point to give you something concrete in which to ground your understanding of how to do transcription. However, there is much dialectal variation in English, so the transcriptions offered here are very general and may differ from the varieties of English you are familiar with.

We begin with consonants, where there tends to be less variation across dialects. Table 3.2 lists some plosives and affricates of English, with their IPA symbol (keeping in mind typographic simplicity) and example words containing each consonant in various positions, where possible. For each word, The portion of the spelling that corresponds to the phone is in bold. Finally, a phonetic description of each consonant is also given.

| symbol | example (beginning) |

example (middle) |

example (end) |

description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [p] | pan | rapid | lap | voiceless bilabial plosive |

| [b] | ban | rabid | lab | voiced bilabial plosive |

| [t] | tan | atop | let | voiceless alveolar plosive |

| [d] | den | adopt | led | voiced alveolar plosive |

| [t͡ʃ] | chin | batches | rich | voiceless postalveolar affricate |

| [d͡ʒ] | gin | badges | ridge | voiced postalveolar affricate |

| [k] | can | bicker | lack | voiceless velar plosive |

| [ɡ] | gain | bigger | lag | voiced velar plosive |

| [ʔ] | — | uh–oh | — | voiceless glottal plosive |

Most of these are straightforward, but as discussed in Section 3.3, the alveolar consonants are normally apicoalveolar, though some speakers may pronounce them with the blade of the tongue. If that detail is necessary, these consonants can be transcribed as [t̻] and [d̻], using the laminal diacritic [ ̻ ]. Regardless of the active articulator, some speakers may pronounce these consonants on the back of the teeth rather than on the alveolar ridge, in which case, they would be transcribed as [t̪] and [d̪], using the dental diacritic [ ̪ ].

The glottal plosive (also frequently called a glottal stop) is only a marginal consonant in English. It can be found as the catch in the throat in the middle of the interjection uh-oh. Some speakers also have it elsewhere, such as in the middle of some British English pronunciations of the word bottle. It is articulated by making a full stop closure with the vocal folds, blocking all airflow through the glottis.

Table 3.3 lists some fricatives of English.

| symbol | example (beginning) |

example (middle) |

example (end) |

description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [f] | fan | wafer | leaf | voiceless labiodental fricative |

| [v] | van | waver | leave | voiced labiodental fricative |

| [θ] | thin | ether | truth | voiceless interdental fricative |

| [ð] | than | either | smooth | voiced interdental fricative |

| [s] | sin | muscle | bus | voiceless alveolar fricative |

| [z] | zone | muzzle | buzz | voiced alveolar fricative |

| [ʃ] | shin | Haitian | rush | voiceless postalveolar fricative |

| [ʒ] | genre | Asian | rouge | voiced postalveolar fricative |

| [h] | hen | ahead | — | voiceless glottal fricative |

The most notable variation here is that some speakers do not have [θ] and [ð], and instead used [t] and [d] or [f] and [v], depending on the dialect and the position in the word. As with the postalveolar affricates mentioned before, the postalveolar fricatives are also usually somewhat rounded, so they could be more narrowly transcribed as [ʃʷ] and [ʒʷ]. The voiced postalveolar fricative [ʒ] is also one of the rarest consonants in English, and many speakers pronounce it as an affricate in some positions instead of as a fricative. For example, you may hear speakers pronounce the final consonant of garage as the affricate [d͡ʒ] rather than the fricative [ʒ].

Table 3.4 lists some sonorants of English. Across the world’s spoken languages, sonorants tend to be voiced by default, because their high degree of airflow causes the vocal folds to spontaneously vibrate, unless extra effort is put in to keep them from vibrating. This is true for English, so the phonation of the sonorants is not listed here.

| symbol | example (beginning) |

example (middle) |

example (end) |

description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [m] | man | simmer | ram | bilabial nasal stop |

| [n] | nun | sinner | ran | alveolar nasal stop |

| [ŋ] | — | singer | rang | velar nasal stop |

| [l] | lane | folly | ball | alveolar lateral approximant |

| [r] | run | sorry | bar | (various! see earlier discussion) |

| [j] | yawn | onion | — | palatal central approximant |

| [w] | won | awake | — | labial-velar central approximant |

A few of these sonorants warrant extra discussion. The alveolar nasal stop [n] has much of the same variation as the alveolar plosives, with some speakers having a laminoalveolar articulation [n̻] and some having a dental articulation [n̪]. The velar nasal stop is often one of the most surprising phones of English to English speakers who are new to phonetics, because is not easily identifiable as its own phone. Many people are misled by the spelling and think they say words like singer with a [ɡ], but in fact, most speakers have only a nasal stop there, so that singer differs from finger, with singer having only [ŋ] and finger having [ŋɡ]. However, there are speakers who do genuinely pronounce all words like these with a [ɡ] after the nasal stop, but even then, the nasal stop they have is still velar [ŋ], not alveolar [n].

A notable consonant here is [w], which is special among the consonants of English in being doubly articulated, which means that it has two equal places of articulation. It is both bilabial (with an approximant constriction between the two lips) and velar (with a second approximant constriction between the tongue back and the velum). Its place of articulation is usually called labial-velar. English used to consistently have two labial-velar approximants, a voiced [w] and a voiceless [ʍ]. Very few speakers today have both of these, but those who do pronounce the words witch and which differently, with voiced [w] in witch and voiceless [ʍ] in which.

Now we can move on to the vowels. This is where much of the variation in pronunciation occurs across English dialects, and fully describing all of the vowels in English would take up an entire textbook of its own. Note that this is not a general property of spoken languages overall. Some are like English, with most dialectal variation in the vowels, but others have much more dialectal variation in the consonants, while others may have a relatively even mixture of variation in both consonants and vowels.

Table 3.5 lists some monophthongs of English, with a focus on the English vowels as they are broadly pronounced across North American dialects. However, there is still much variation just in North America, and this discussion should not be taken to represent any particular speaker or region, let alone any sort of idealized standard or target pronunciation. This is simply a convenient abstraction that provides a useful baseline, though it is still only a very rough guide, and individual speakers can vary quite a lot from what is discussed here. Note also that unstressed vowels are very unstable, especially in fast speech, so for example, unstressed [u] could be pronounced more like [ʊ] or [ə], even for the same speaker saying the same word. As in most spoken languages, the vowels of English are generally all voiced, so their phonation is not listed here. Example words are given that show the vowel in a stressed syllable, an unstressed syllable, and at the end of the word (see Sections 3.10 and 3.11 for more about syllables and stress).

| symbol | example (stressed) |

example (unstressed) |

example (end) |

description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [i] | beater | saltier | see | high front unrounded tense |

| [ɪ] | bitter | — | — | high front unrounded lax |

| [e] | baker | — | say | mid front unrounded tense |

| [ɛ] | better | — | — | mid front unrounded lax |

| [æ] | batter | — | — | low front unrounded |

| [ɑ] | father | — | spa | low back unrounded |

| [ɒ] | bonnet | — | — | low back round |

| [ɔ] | border | — | saw | mid back round lax |

| [o] | boater | — | sew | mid back round tense |

| [ʊ] | booker | — | — | hiɡh back round lax |

| [u] | boomer | manual | sue | hiɡh back round tense |

| [ʌ] | butter | — | — | mid central unrounded lax (stressed) |

| [ə] | — | animal | sofa | mid central unrounded lax (unstressed) |

As noted before, there is a lot of variation that cannot be adequately discussed here, so we only cover a few notable deviations. First, while many speakers pronounce the four tense vowels as monophthongs as transcribed here, most speakers pronounce some or all of them as diphthongs instead, perhaps even having an approximant at the end rather than a vowel. For example, high front unrounded tense [i] may be pronounced more like [ɪi] or [ij] by some speakers. It is especially common for the two tense mid vowels to be pronounced as diphthongs, something like [eɪ] and [oʊ] or perhaps [ej] and [ow].

Many of the back round vowels, especially [ʊ], are fronter and/or unrounded for some speakers in some dialects.

The back vowels in bore and bought are pronounced similarly to each other by some North Americans, and so they are often represented with the same symbol [ɔ], though note there may still be some differences, with [ɔ] before a rhotic often pronounced somewhat higher, closer to [o]. However, many speakers in Canada and in the western United States have a very different vowel in bought from bore. Their bought vowel is much lower, and for some speakers, it is also unrounded. These speakers use the same low vowel in bought that they use in bot. For most North Americans, the low vowels in bot and balm are pronounced the same, either as back round [ɒ] or back unrounded [ɑ]; in some dialects, it may be central unrounded [a]. Others have two different vowels for these words, usually [ɒ] in bot and [ɑ] or [a] in balm. Needless to say, this part of the vowel system of English is particularly troublesome, and even many expert linguists get aspects of it wrong.

The two mid central vowels [ʌ] and [ə] are often treated as related pronunciations of the same vowel, based on whether or not they occur in a stressed syllable (again, see Sections 3.10 and 3.11 for more about syllables and stress). For now, just note that some vowels of English are pronounced louder and longer than others, which we call stressed, while the other softer and shorter vowels are said to be unstressed. We can see the difference in stress in pairs like billow and below, which differ mostly in which syllable is stressed: the first syllable in billow and the second syllable in below. The two central vowels of English differ in stress: the first syllable of the name Bubba is stressed, and the second is unstressed, so we might transcribe this name as [bʌbə]. Although these two vowels sound very similar for many speakers and could easily be notated with the same symbol, there is a long tradition of notating the unstressed mid central vowel of English with [ə] and the stressed mid central vowel with [ʌ], based on historical pronunciations in which the stressed vowel used to be pronounced much farther back (and still is, in some dialects).

Finally, we consider diphthongs and syllabic consonants, which are phones that have consonant-like constrictions in the vocal tract but which function more like vowels within English. Some diphthongs and syllabic consonants of English are given in Table 3.5.

| symbol | example (stressed) |

example (unstressed) |

example (end) |

description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [aɪ] | biter | — | sigh | low central unrounded to high front unrounded diphthong |

| [aʊ] | browner | — | how | low central unrounded to high back round diphthong |

| [ɔɪ] | boiler | — | soy | mid back round to high front unrounded diphthong |

| [r̩] | burning | interval | sir | syllabic rhotic |

| [l̩] | — | hazelnut | saddle | syllabic alveolar lateral approximant |

| [n̩] | — | calendar | sudden | syllabic alveolar nasal stop |

| [m̩] | — | bottomless | seldom | syllabic bilabial nasal stop |

For the diphthongs, the symbols used here represent a rough average over where they typically start and end, but the actual pronunciation varies quite a lot from speaker to speaker and even for the same speaker. The low starting point for [aɪ] and [aʊ] may be closer to back [ɑ] or front [æ], while the mid back starting point for [ɔɪ] may be closer to tense [o]. Additionally, the hiɡh front ending point for [aɪ] and [ɔɪ] may be closer to tense [i] or the approximant [j], while the hiɡh back ending point for [aʊ] may similarly be closer to tense [u] or the approximant [w].

Syllabic consonants are transcribed by using the syllabic diacritic [ˌ] under the relevant consonant symbol. However, sometimes these are transcribed with a preceding [ə] instead, so that hazelnut could be transcribed either as [hezl̩nʌt] or as [hezəlnʌt]. Syllabic rhotics (also called rhotacized vowels or r-coloured vowels) are so common that they have their own dedicated symbols: [ɝ] in stressed syllables and [ɚ] in unstressed syllables. Thus, burning could be transcribed as [br̩nɪŋ] or [bɝnɪŋ], while interval could be transcribed as [ɪntr̩vl̩] or [ɪntɚvl̩].

With all of this variation, not just in pronunciation by different speakers, but in transcription choices by different linguists, it can be difficult to figure out what is really intended by a given transcription. This is why when exact phonetic details matter, it is a good idea not to rely solely on the IPA, but to include prose descriptions, midsagittal diagrams, and other tools that can help clarify exactly what is meant.

Check your understanding

References

Cheng, Chin-Chuan. 1973. A synchronic phonology of Mandarin Chinese. Monographs on Linguistic Analysis. The Hague: Mouton.

Chitoran, Ioana. 2002. The phonology and morphology of Romanian diphthongization. Probus 14(2): 205–246.

DeLattre, Pierre, and Donald C. Freeman. 1968. A dialect study of American r’s by x-ray motion picture. Linguistics 44: 29–68

Demers, Richard A. and George M. Horn. 1978. Stress assignment in Squamish. International Journal of American Linguistics 44(3): 180–191.

Foulkes, Paul, and Gerard J. Docherty. 2000. Another chapter in the story of /r/: Labiodental variants in British English. Journal of Sociolinguistics 4(1): 30-59.

Johnston, Paul. 1997. Regional variation. In Charles Jones, ed. The Edinburgh history of the Scots language. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. 433–513.

Maguire, Warren. 2017. Variation and change in the realisation of /r/ in an isolated Northumbrian dialect. In Chris Montgomery and Emma Moore, eds. Language and a sense of place: Studies in language and region. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 87–104.

Olson, Kenneth S., and John Hajek. 1999. The phonetic status of the labial flap. Journal of the International Phonetic Association 29(2): 101–114.