[in progress] Chapter 14: Historical Linguistics

14.9 Case study: Reconstructing Proto-Chinese

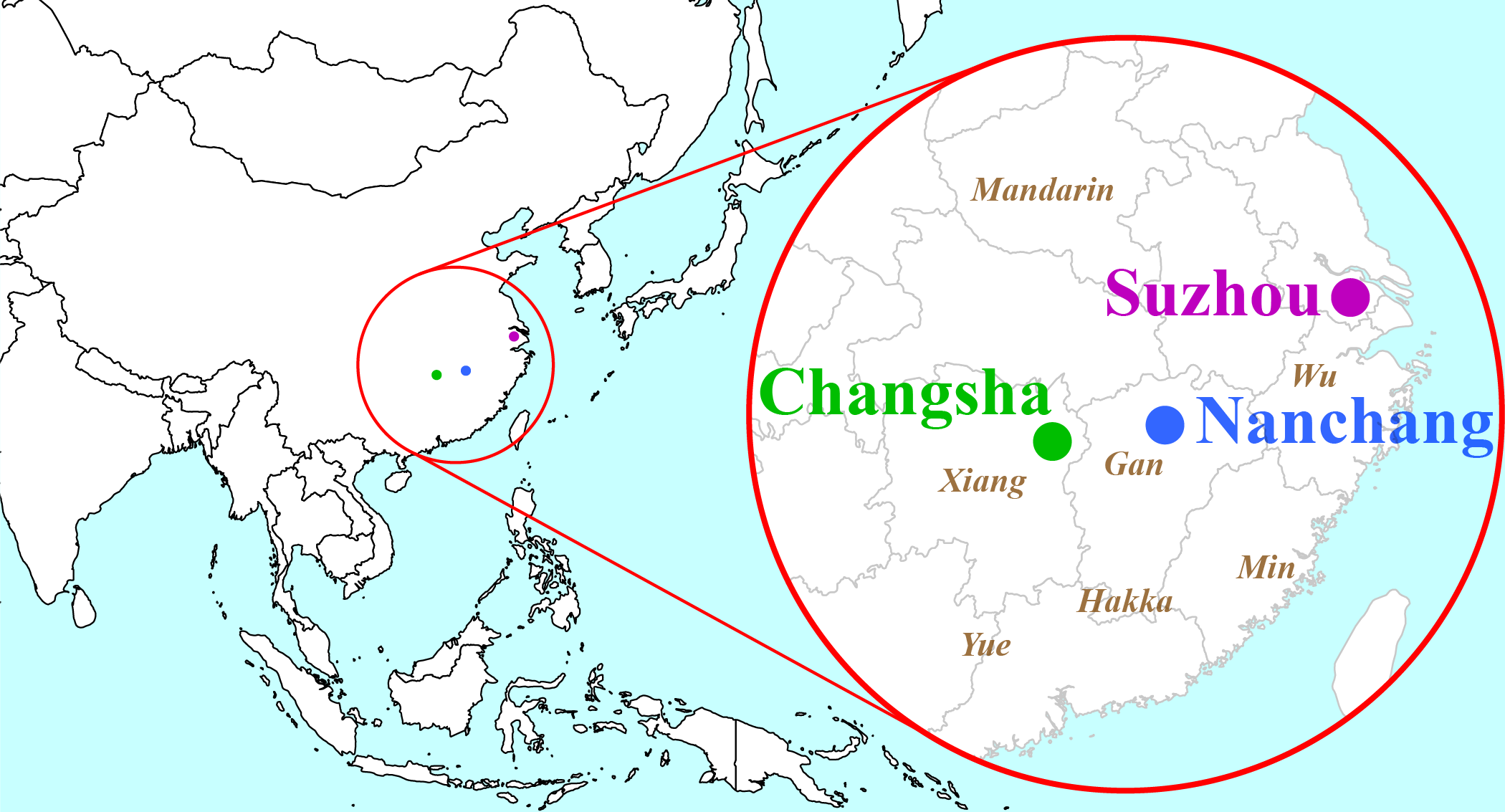

In this section, the comparative method is demonstrated with data adapted from 音第汉语方音字汇 (Hànyǔ fāngyīn zìhuì) (1989), a massive collection of 2,722 cognate sets from 20 varieties of Chinese. For simplicity, we consider data from only three specific varieties: the Changsha dialect of the Xiang branch of Chinese, the Nanchang dialect of the Gan branch, and the Suzhou dialect of the Wu branch. There are many other languages that would need to be studied in a full diachronic analysis of Chinese, including other dialects from these three branches (Shuangfeng, Yichun, Shanghainese, etc.) and from the other branches of Chinese (Yue, Min, Hakka, Mandarin, etc.).

The approximate locations of Changsha, Nanchang, and Suzhou are given in the map in Figure 14.12, along with approximate locations of multiple branches of the Chinese language family.

For the purposes of this reconstruction, tone is not transcribed or analyzed here, since its behaviour is quite complex across the Chinese languages and is beyond the scope of this discussion.

Building a proto-language

We can begin by considering the single cognate set in (1). These are the three cognates for ‘compare’ in Changsha, Nanchang, and Suzhou. Note that they are all pronounced the same way, as [pi].

| Changsha | Nanchang | Suzhou | ||||

| (1) | 比 | ‘compare’ | pi | pi | pi |

In a case like this, when there is no other information to draw from, we can make a reasonable hypothesis that [pi] was also the pronunciation for the etymon for these cognates (this is the same reasoning used for comparing English house and German Haus ‘house’ in Section 14.8). We do not know this for sure, since Ancient Chinese writing does not contain enough phonetic information to reliably know how words were pronounced. Where there is some phonetic information, we find that it tends to agree with the results of the comparative method (see Section 4.10 for more discussion of this general issue). To mark our uncertainty, we can use an asterisk * before the reconstructed pronunciation: *[pi]. The asterisk indicates that the reconstructed form is a hypothesis rather than a directly attested fact.

When using the comparative method, we typically use the special prefix proto- for reconstructed objects, so that the reconstructed word *[pi] would be called a proto-word, which is our best guess at what the actual etymon was. The individual reconstructed phones of a proto-word are called proto-sounds, and a reconstructed language is called a proto-language. For a specific language, we can add proto- to the language name, so here, we are using Changsha, Nanchang, and Suzhou to reconstruct Proto-Chinese. We can update our analysis of (1) by including a fourth column for our hypothesized reconstruction of Proto-Chinese.

| Changsha | Nanchang | Suzhou | Proto-Chinese | ||||

| (1) | 比 | ‘compare’ | pi | pi | pi | *pi |

It is important to note that a proto-word is not an actual etymon, and a proto-language is not an actual language. Reconstructed objects are theoretical representations of a proposed historical relationship between languages. The Changsha, Nanchang, and Suzhou varieties of Chinese are real languages used by real human beings, but Proto-Chinese is an abstraction that was never used by any human beings as a language. It is a hypothetical approximation of some actual ancestral version of Chinese that we do not have records of. However, the name of a proto-language is sometimes used informally when talking about the real language it approximates, but this is not technically correct and should be avoided.

There are many other similar consistent cognate sets across the three languages. If all of the cognates are pronounced the same way, and we have no further information to rely on, then it is reasonable to reconstruct a proto-word for those cognates with the same pronunciation.

Thus, for the data in (1)–(7), we would reconstruct the Proto-Chinese forms as shown in the right column, because they are identical to all three cognates in the corresponding cognate sets. With no variation between languages, we do not have justification at this point to hypothesize anything else for Proto-Chinese except equivalence with the modern languages.

| Changsha | Nanchang | Suzhou | Proto-Chinese | ||||

| (1) | 比 | ‘compare’ | pi | pi | pi | *pi | |

| (2) | 披 | ‘wear’ | pʰi | pʰi | pʰi | *pʰi | |

| (3) | 帝 | ‘emperor’ | ti | ti | ti | *ti | |

| (4) | 梯 | ‘ladder’ | tʰi | tʰi | tʰi | *tʰi | |

| (5) | 例 | ‘example’ | li | li | li | *li | |

| (6) | 米 | ‘rice’ | mi | mi | mi | *mi | |

| (7) | 泥 | ‘mud’ | ni | ni | ni | *ni |

The importance of regular change

Of course, the fact that these three languages are different languages means that they must have some differences somewhere. So there are some cognate sets in which at least one language is different from the others. This happens for the cognate set for ‘skin’, where the three languages all differ (8). Since we do not have perfect identity across the three languages, we cannot reconstruct a proto-word as easily for cognate sets (1)–(7). We can temporarily mark the unknown Proto-Chinese reconstruction with a question mark (?).

| Changsha | Nanchang | Suzhou | Proto-Chinese | ||||

| (8) | 迷 | ‘skin’ | pi | pʰi | bi | ? |

In cases like this, it is often useful to focus on individual phones across a cognate set, so that they can be analyzed separately from the rest of the word. This is called a correspondence set, which is often notated with a colon between each phone, as in the correspondence sets for the consonants (9a) and vowels (9b) of the cognates for ‘skin’.

| (9) | a. | p | : | pʰ | : | b |

| b. | i | : | i | : | i |

While we cannot immediately reconstruct the entire proto-word, we can try to reconstruct it proto-sound by proto-sound. When we have a correspondence set of the form X : X : X, as we do in (9b) for the vowel, it is reasonable to reconstruct *X as the relevant proto-sound, similar to how we can reconstruct an entire proto-word when all of the cognates are pronounced the same way.

So we can begin by reconstructing *[i] for the vowel in the proto-word for ‘skin’, since the vowel is [i] in all three cognates. We can use an ellipsis (…) to indicate the remainder of the proto-word that we cannot yet reconstruct (here, just the initial proto-consonant), leaving the question mark in place to represent that the reconstruction is incomplete.

| Changsha | Nanchang | Suzhou | Proto-Chinese | ||||

| (8) | 迷 | ‘skin’ | pi | pʰi | bi | *…i? |

The cognates sets for ‘compare’ (1), ‘wear’ (2), and ‘skin’ (8) have some overlap, so it is worth comparing them more directly. They are repeated below together for convenience.

| Changsha | Nanchang | Suzhou | Proto-Chinese | ||||

| (1) | 比 | ‘compare’ | pi | pi | pi | *pi | |

| (2) | 披 | ‘wear’ | pʰi | pʰi | pʰi | *pʰi | |

| (8) | 迷 | ‘skin’ | pi | pʰi | bi | *…i? |

Without changing our analysis of ‘compare’ and ‘wear’, we have a few options for reconstructing the proto-word for ‘skin’: either it is *[pi] (identical to the proto-word for ‘compare’), *[pʰi] (identical to the proto-word for ‘wear’), or something else. If we reconstruct *[pi] for both ‘compare’ and ‘skin’, we run into a problem. Based on (1), we have proposed that Proto-Chinese *[p] regularly corresponds to [p] in all three modern languages. But if that is the case, then how does *[p] end up as [pʰ] in the Nanchang word for ‘skin’ and as [b] in the Suzhou word for ‘skin’? Perhaps this was sporadic change, and Nanchang and Suzhou just randomly changed the pronunciation of *[pi] ‘skin’ but not *[pi] ‘compare’, while Changsha kept both words unchanged. This kind of sporadic change does happen, so we cannot rule out the possibility here.

Similarly, if we instead reconstruct *[pʰi] for ‘skin’, then it would seem that Changsha and Suzhou both randomly changed this word but not *[pʰi] ‘wear’, while Nanchang kept both words unchanged. Again, this is possible.

However, the p : pʰ : b correspondence set is not unique to ‘skin’; there are many other cognate sets that have this same pattern. Similarly, there are many cognate sets for both of the p : p : p and pʰ : pʰ : pʰ correspondence sets. Two examples of each of the three correspondence sets are given in (10)–(15).

| Changsha | Nanchang | Suzhou | Proto-Chinese | ||||

| (10) | 本 | ‘root’ | pən | pən | pən | *pən | |

| (11) | 聘 | ‘employ’ | pin | pin | pin | *pin | |

| (12) | 噴/喷 | ‘spray’ | pʰən | pʰən | pʰən | *pʰən | |

| (13) | 品 | ‘personality’ | pʰin | pʰin | pʰin | *pʰin | |

| (14) | 盆 | ‘tub’ | pən | pʰən | bən | *…ən? | |

| (15) | 貧/贫 | ‘poor’ | pin | pʰin | bin | *…in? |

Since all three of these correspondence sets are supported by many examples, this does not appear to be the result of sporadic change in a small handful of words. Instead, the correspondence sets represent robust patterns across the languages. This suggests we should look for regular changes that predictably affected all eligible words, rather than many unpredictable sporadic changes for many individual words.

This means that we need to reconstruct three different proto-sounds, one for each of the correspondence sets. As before, it still seems reasonable to reconstruct *[p] for p : p : p and *[pʰ] for pʰ : pʰ : pʰ, so we should reconstruct a different third proto-sound for p : pʰ : b. The next most reasonable option is *[b], since [b] is the only remaining phone in the correspondence set. This gives us the updated analysis of the relevant words in (8), (14), and (15), which have *[b] for the p : pʰ : b correspondence set in the first consonant, in contrast to *[p] and *[pʰ].

| Changsha | Nanchang | Suzhou | Proto-Chinese | ||||

| (8) | 迷 | ‘skin’ | pi | pʰi | bi | *bi | |

| (14) | 盆 | ‘tub’ | pən | pʰən | bən | *bən | |

| (15) | 貧/贫 | ‘poor’ | pin | pʰin | bin | *bin |

To complete the analysis, we need to explain why *[b] > [p] in Changsha. This is an example of devoicing, which is common in the world’s spoken languages, especially for voiced plosives. Voicing requires continuous airflow through the glottis into the oral cavity, but plosives have a complete closure in the oral cavity. This means that air pressure will continue to build up, making it difficult to maintain both the stop closure and the airflow for voicing. Thus, some languages give up on voiced plosives and only have voiceless plosives. This appears to have happened in Changsha.

We also need to explain why *[b] > [pʰ] in Nanchang. This could be a case of devoicing, but then we still need to explain why there is also aspiration. It cannot be the case that all voiceless plosives in Nanchang are aspirated, since original *[p] remains unaspirated as [p]. Sometimes, we may not have an easy explanation for why a particular sound change occurs, and this is one of those cases.

We further suppose that these sound changes were regular, affecting all proto-words containing *[b]. Further data might reveal that a bit more complicated analysis is needed, but the analysis here demonstrates the basic principles of the comparative method.

Conservative and innovative languages

Finally, we might notice that Suzhou retains the Proto-Chinese pronunciation for all of the examples so far, so that the proto-words we reconstruct for Proto-Chinese look exactly like the modern words in Suzhou. In cases like this, we might say that Suzhou is conservative, since it appears not to have changed over the same time period as the other languages it is related to. Those languages can be said to be innovative, since they have undergone one or more changes.

However, we can find examples where Suzhou is innovative. For example, consider the cognate sets for ‘root (10) and ‘collapse’ (16).

| Changsha | Nanchang | Suzhou | Proto-Chinese | ||||

| (8) | 本 | ‘root’ | pən | pən | pən | *pən | |

| (16) | 崩 | ‘collapse’ | pən | pɛn | pən | *p…n? |

Since we have already reconstructed *[pən] for ‘root’, we cannot use it again for ‘collapse’, which has a different vowel in Nanchang. Since we have two distinct correspondence sets, ə : ə : ə and ə : ɛ : ə, we should reconstruct two distinct proto-sounds. As before, we pick the only remaining option among the modern phones, which means we reconstruct *[ɛ] for the ə : ɛ : ə correspondence set, giving us *[pɛn] as the proto-word for ‘collapse’ (16).

| Changsha | Nanchang | Suzhou | Proto-Chinese | ||||

| (16) | 崩 | ‘collapse’ | pən | pɛn | pən | *pɛn |

This requires a sound change *[ɛ] > [ə] that affected both Changsha and Suzhou, leaving Nanchang more conservative, at least with respect to this particular vowel.

Since all of the modern languages now have at least one change, that means none of them are truly conservative. Indeed, this is normally the case when we do a full analysis of a family of languages, especially over a large time scale. Languages naturally change over time, so we tend not to find living languages that are purely conservative. Just as we saw with the concept of complexity, it is more accurate to say that some aspects of a language may be conservative, while others may be innovative.

Check your understanding

References

北京大学 中国语言文学系 语言学教研室 (Běijīng dàxué zhōngguó yǔyán wénxué xì yǔyán xué jiàoyánshì) [Peking University, Department of Chinese Language and Literature, Linguistics Teaching and Research Section], ed. 1989. 音第汉语方音字汇 (Hànyǔ fāngyīn zìhuì) [Phonetic Dictionary of Chinese Dialects], second edition. Beijing: Wénzì Gǎigé Chūbǎnshè.