Chapter 10: Language Variation and Change

10.2 Language varies

All languages have variation

In the earlier parts of this book, you’ve already observed that a lot of the work linguists do involves making comparisons between sounds, signs, words, or sentences in two or more different languages, dialects, or varieties. Before we get any farther, we need to think about the word dialect:

Language, dialect, variety. It’s common for people to use the word dialect to imply that certain ways of languaging are substandard, low status, non-prestigious, geographically-isolated, or some deviation from some ‘standard’ version of the language. But we know from Chapter 2 that everyone has a dialect, and a so-called ‘standard language’ is not better in any linguistic way; it’s just the dialect that has more social prestige associated with it. Remember that linguistics doesn’t rank languages and dialects in a hierarchical way: dialects are just subdivisions of a language. The term variety doesn’t have those same negative social connotations as dialect, so we’ll usually call subdivisions of a language varieties in this chapter.

Ok, back to making comparisons between language forms. These two sentences, one in Icelandic (1) and and one in Danish (2), both express the same meaning. They’re equivalent to English, “I didn’t ask why Peter hadn’t read it.”

| (1) |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (2) |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Notice that there are two negative morphemes in this sentence: one associated with the verb ask and one with the verb read. In the gloss (the morpheme-by-morpheme translation below each sentence), the negative morphemes are indicated with the upper-case NEG.

These two examples come from two different languages, so it’s not surprising that the words and morphemes differ between them. And at the same time, there are some similarities between the words, which we might expect since these two languages are closely related to each other.

The difference we’re interested in is the order of the negative marker and the verb in the embedded clause “Peter hadn’t read it”. In Icelandic, the order is hafði ekki ‘have not’ while in Danish it’s ikke havde ‘not have’. These two languages have two different ways of doing the same thing: we’ll call this cross-linguistic variation.

But there can also be variation within a single language or variety, and even within a single person depending on the context. Look at this rhyming couplet (3) from Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet (386, 670):

| (3) |

|

This example shows the exact same word order variation that we observed between Icelandic and Danish but here, the two different ways of doing the same thing appear within the same language! The Early Modern English variety of Shakespeare’s time allowed for both options: the VERB-NEGATIVE order like Icelandic and the NEGATIVE-VERB order like Danish. (To learn more about the do-support in Juliet’s word order, see Chapter 6). Within this one rhyming couplet, we can observe sociolinguistic variation: two or more ways of doing the same thing within one language, one variety, and one individual writer.

What’s a linguistic variable?

When there’s more than one way to do the same thing in language, that’s called a linguistic variable. The individual options that language users choose are called variants. So in the Early Modern English example above: the variable is the option for either word order: negative-verb or verb-negative. Juliet uses one variant and Romeo uses the other. So the variable is an abstract set: There’s no single piece of language behaviour that we can point to as a variable. We only ever observe the abstract variable when a language user uses one of the variants.

Linguistic variables exist in all languages and varieties, in all modalities, and at all domains of language from the phonetic to the pragmatic. Here [in the next video!] are some examples of linguistic variables from different languages and different domains of language.

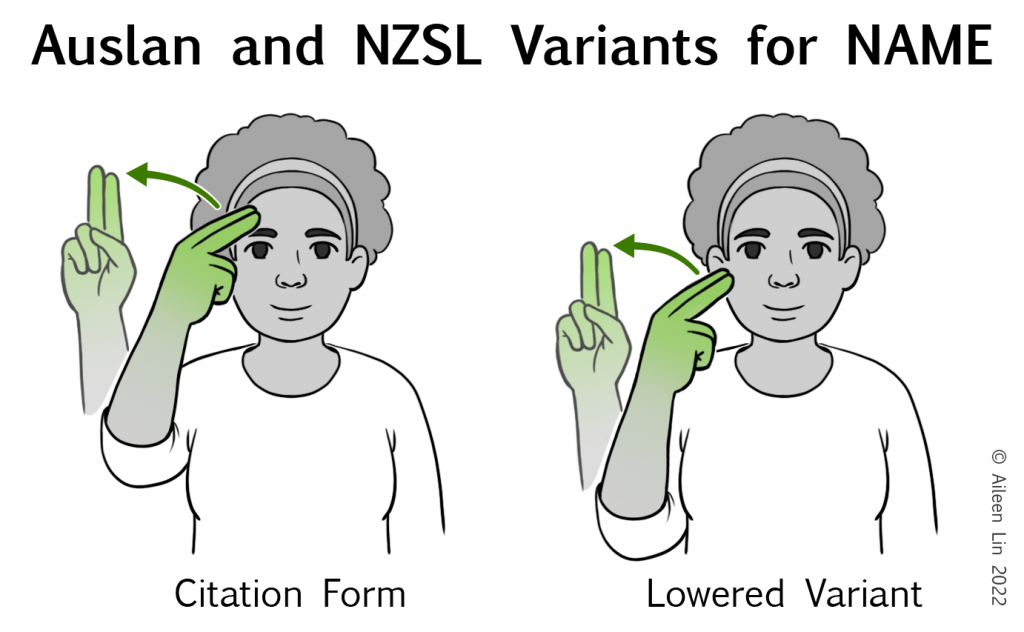

In Auslan, New Zealand Sign Language, and American Sign Language, some signs like KNOW, THINK, and NAME, have variable location: at the forehead or lowered to near the cheek (Bayley, Schembri, and Lucas 2015).

This figure shows the two variants of the sign for NAME in Auslan and New Zealand Sign Language. The linked video shows the variants for KNOW in American Sign Language.

This is an example of phonetic-phonological variation. The variants differ from each other in the articulatory parameter of location.

Another kind of phonetic-phonological variable involves variation between the presence and absence of a phone. In Beijing Mandarin, a syllable without a coda can be variably rhoticized. For example the word meaning ‘bag’ has two different variants: it can be spoken with no coda consonant (包 bao [paw]) or with a rhotic coda (包儿 baor [pawr]) (Zhang 2008).

We also find linguistic variables in the morphophonological domain of languages. In contemporary varieties of London English, especially among immigrant youth of colour, the word a exhibits variation when it’s followed by a word beginning with a vowel. Two different variants, an and a, are both possible, as in an apple [ənæpl] and a apple [əʔæpl] (Gabrielatos, Torgersen, Hoffmann, and Fox 2010).

We can also find morphosyntactic variables in languages. In North Baffin Inuktitut, transitive constructions can occur variably with ergative alignment or antipassive alignment. These alignment types differ in terms of the morphological case that nouns have and the kind of agreement morphology that appears on verbs.

These two sentences both mean, “I see a dog”. And the root forms of the verb see and the noun dog are the same in both sentences.

|

||||||||

| (4b) |

|

|||||||

With ergative alignment, as in (4a), the object is marked with absolutive case (which appears as a null morpheme -ø) and the verb agrees with both subject and object (which appears as the morpheme -jara). With antipassive alignment, as in (4b), the object is marked with an oblique case (it occurs with the morpheme -mit) and the verb agrees only with the subject (which appears as the morpheme -vunga) (Carrier 2020).

Languages can also have linguistic variables with variants that differ in multiple ways, across different domains. For example, in Tagalog, the meaning of adjectives can be intensified with several variants that differ lexically, morphologically, and morphosyntactically from each other variant, as in these examples (Umbal 2019).

| (5a) |

|

||||||||||||||||

| (5b) |

|

||||||||||||||||

| (5c) |

|

||||||||||||||||

| (5d) |

|

|||||||||||||

This first variant uses a free morpheme sobra, basically a word like English very, or really. There are two morphosyntactic variants: the adjective can be reduplicated, or a bound morpheme can be affixed. Or the same meaning can be conveyed with a syntactic variant like this exclamative construction.

These are just a small handful of examples of linguistic variables in different languages and in different domains of language. All languages have variation like this in all the different parts of a language’s grammar.

What isn’t a linguistic variable?

When we’re observing a linguistic variable in any domain of the grammar, a key attribute is that the variants all do the same thing in some way. They all intensify the adjective, or they all make a declarative sentence into a question, or they all represent the same word. Before moving on, let’s examine a couple of similar linguistic concepts that are not linguistic variables.

Synonyms are often confused with linguistic variables. Synonyms are sets of words that have similar meanings like car, automobile, ride, horseless carriage, jalopy, hooptie and paddock basher. All these words denote a four-wheeled, motor vehicle that many people drive. These synonyms certainly seem like they’re multiple ways of doing the same thing but they’re not actually interchangeable the way that variants of linguistic variables are. For example, jalopy, hooptie, and paddock basher connote that the vehicle is old or run-down; you might use ride in informal contexts and automobile in formal contexts. Some options might appear only in certain regional or social varieties. For example, jalopy is an older North American English term, hooptie is typically associated with Black English, and paddock basher is a term mostly only found in Australia, referring to a car only suitable to drive around on a farmer’s field. Some of these options have become obsolete: you might only hear horseless carriage today if you’re watching a historical show like Downton Abbey. Because of the different connotations or the particular regional and social usages, synonyms like these are not usually interchangeable in the same way as linguistic variants.

Just to make things a little more complicated, sometimes synonyms do behave as variables: if the choice between options systematically co-varies with social and/or linguistic constraints. In other words, if which variant word you use depends on your social location, then a linguist might analyze those synonyms as linguistic variables. For example, in English adjectives of positive evaluation like cool, awesome, sick, neat, and great correlate with linguistic and social constraints (Tagliamonte and Pabst 2020).

The other kind of variation that doesn’t count as a linguistic variable is a categorical alternation like the phonological rules we learned in Chapter 4. Categorical alternations depend strictly on the linguistic context that they appear in, not the social context. For example, in many varieties of English, the form of the plural suffix depends entirely on the phonological environment. Most words get pluralized by adding the [z] phone, like dogs, cars, apples, songs, and bananas. If a word ends in a voiceless consonant, the plural suffix is the [s] phone, like in cats, books, cliffs, apricots. And if a word ends in a particular class of consonants called stridents, the plural gets an extra vowel added, like horses, fridges, peaches. Which form you use is predictable depending on the linguistic environment. In other words, the choice between the options is deterministic.

In contrast, linguistic variables can vary even within the same linguistic environment. But just because this variation is not deterministic, that doesn’t mean it’s random! Instead, linguistic variables are probabilistic in nature. To use the wording of one of the foundational studies in variationist sociolinguistics, there is order amid the heterogeneity (Weinreich, Labov, and Herzog 1968: 100). The choice between different variants of a linguistic variable is subject to probability given many different possible conditioning factors or constraints. These conditioning factors can include aspects of the linguistic context. So think about this English sentence (6).

(6) I’m fishing this morning.

You’ve probably noticed that English words that end with -ing sometimes get pronounced as [ɪŋ] and sometimes as [ɪn]. That’s a linguistic variable! Like all linguistic variables, the choice between [ɪn] and [ɪŋ] isn’t random. In most varieties of English, the [ɪn] variant is more likely to occur in verbs than in nouns. It’s likelier to show up in [fɪʃɪn] than in [mɔɹnɪn]. So syntactic category is a conditioning factor for this variable. But the conditioning factors for this variable also include social factors. That’s where the socio- comes into variationist sociolinguistics. Whether someone uses the [ɪn] variant or the [ɪŋ] on any given occasion depends on social facts about the speaker, and about who they’re talking to and on other sociocultural aspects of the interaction.

The field of sociolinguistics counts and quantifies variants of linguistic variables to uncover social facts as well as linguistic facts.

References

Bayley, R., Schembri, A., and Lucas, C. (2015). Variation and change in sign languages. In A. Schembri and C. Lucas (eds.) Sociolinguistics and Deaf Communities. Cambridge University Press. pp. 61–94.

Carrier, J. (2017). The ergative-antipassive alternation in Inuktitut: Analyzed in a case of new-dialect formation. The Canadian Journal of Linguistics / La revue canadienne de linguistique 62(4), 661-684. https://www.muse.jhu.edu/article/678231.

Gabrielatos, C., Torgersen, E. N., Hoffmann, S., & Fox, S. (2010). A Corpus-Based Sociolinguistic Study of Indefinite Article Forms in London English. Journal of English Linguistics, 38(4), 297–334. https://doi.org/10.1177/0075424209352729

Tagliamonte, S. A., & Pabst, K. (2020). A Cool Comparison: Adjectives of Positive Evaluation in Toronto, Canada and York, England. Journal of English Linguistics, 48(1), 3–30. https://doi.org/10.1177/0075424219881487

Umbal, P. (2019). Contact-induced change in Heritage Tagalog: Evidence from adjective intensification. PhD generals paper: University of Toronto.

Weinreich, U., Labov, W., & Herzog, M. (1968). Empirical foundations for a theory of language change. University of Texas Press.

Zhang, Q. (2005). A Chinese yuppie in Beijing: Phonological variation and the construction of a new professional identity. Language in Society, 34(3), 431-466. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047404505050153