Chapter 3: Phonetics

3.2 Speech articulators

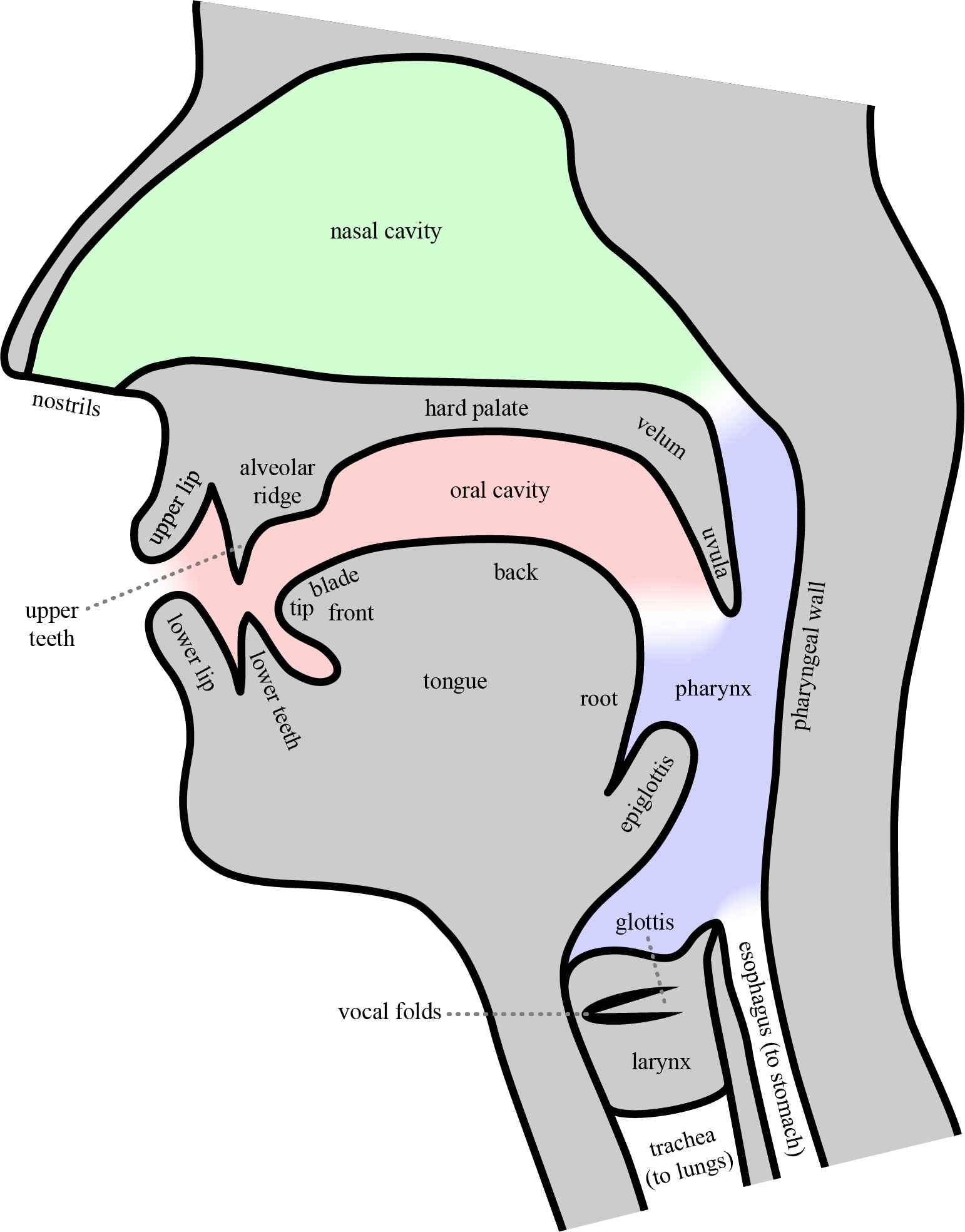

Overview of the vocal tract

Remember that the term articulation means using parts of the body to produce a language signal. For spoken language, articulation happens primarily in the vocal tract, using the lips, tongue, and other parts of the mouth and throat.

Linguists often use this kind of diagram (Figure 3.2) to depict the vocal tract. It’s called a midsagittal diagram, and it represents the inside of the head as if it were split down the middle between the eyes. The convention is to orient a midsagittal diagram this way, with the nostrils and lips on the left and the back of the head on the right. Let’s look more closely at the parts of the vocal tract.

Open spaces in the vocal tract

Let’s start with the three important open regions of the vocal tract. The oral cavity is basically the inside of the mouth, from the lips to the back of the tongue. Behind the tongue is the pharynx, which forms the upper part of what we usually think of as the throat. The other important region is the nasal cavity: the open space in the head above the oral cavity and pharynx, from the nostrils backward and down to the pharynx. Note that these are general terms for these regions: there aren’t precise boundaries between them.

The bottom of the pharynx splits into two tubes: the trachea (also known as the windpipe), which leads down to the lungs, and the esophagus, which leads down to the stomach. We don’t need to pay attention to the esophagus for phonetics, but the trachea is important, since most spoken language is articulated with air coming from the lungs, which speakers manipulate when it passes from the trachea to the pharynx.

Phones as a basic unit of speech

Humans use the parts of the vocal tract in various ways to articulate speech sounds. In linguistics we call individual speech sounds phones or segments. A phone is, roughly, an individual unit of speech that can part of a word in a given language. For example, the four English words spill, slip, lisp, and lips each contain the same four phones, just in different orders. (There is some some slight variation in how each phone is pronounced in different positions in the word, which we’ll examine more in a later chapter.)

Each spoken language has a slightly different inventory of sounds that count as phones in its grammar. The [θ] sound articulated with the tongue between the teeth is pretty frequent in English but rare in most other languages. And on the other hand, Hadza (a language isolate spoken in Tanzania; Sands et al. 1996) and isiZulu (a.k.a. Zulu, a Southern Bantu language of the Niger-Congo family, spoken in southern Africa; Poulos and Msimang 1998) have phones like the alveolar click [!] and the lateral click [ǁ], which are not phones in English, even though some English speakers them non-linguistically, to express disapproval or to urge someone to hurry.

The criterion for whether a given sound is a phone in the grammar of a given language is whether it appears in ordinary words in that language. In applying that criterion, we want to avoid marginal word-like expressions that we sometimes intersperse into our speech. For example, in an English sentence like, “Ugh, I can’t believe you’re eating that,” ugh is sort of like a word, but that rough gravelly sound doesn’t otherwise show up in English words, so we don’t count it as an English phone.

Humans can also produce many other sounds with the vocal tract like burps or snorts or raspberries. We don’t tend to study those sounds in phonetics because they’re not known to be phones in the grammar of any spoken language. But non-speech sounds can still convey non-linguistic meaning. For example, when I make a raspberry sound with my lips, I’m usually expressing a feeling of frustration or exhaustion, and I’m doing so without language

To wrap up, in this section you’ve learned the names for some of the parts of the vocal tract that are used for articulating spoken language. Linguists classify speech sounds according to how they’re articulated, and one of the most fundamental distinctions between phones is whether they are consonants or vowels. The next few sections consider consonants and vowels in more detail, according to their articulation.

Check your understanding

References

Poulos, George, and Christian T. Msimang. 1998. A linguistic analysis of Zulu. Pretoria: Via Afrika.

Sands, Bonny, Ian Maddieson, and Peter Ladefoged. 1996. The phonetic structures of Hadza. Studies in African Linguistics 25(2): 171–204.