Chapter 3: Phonetics

3.1 Modality

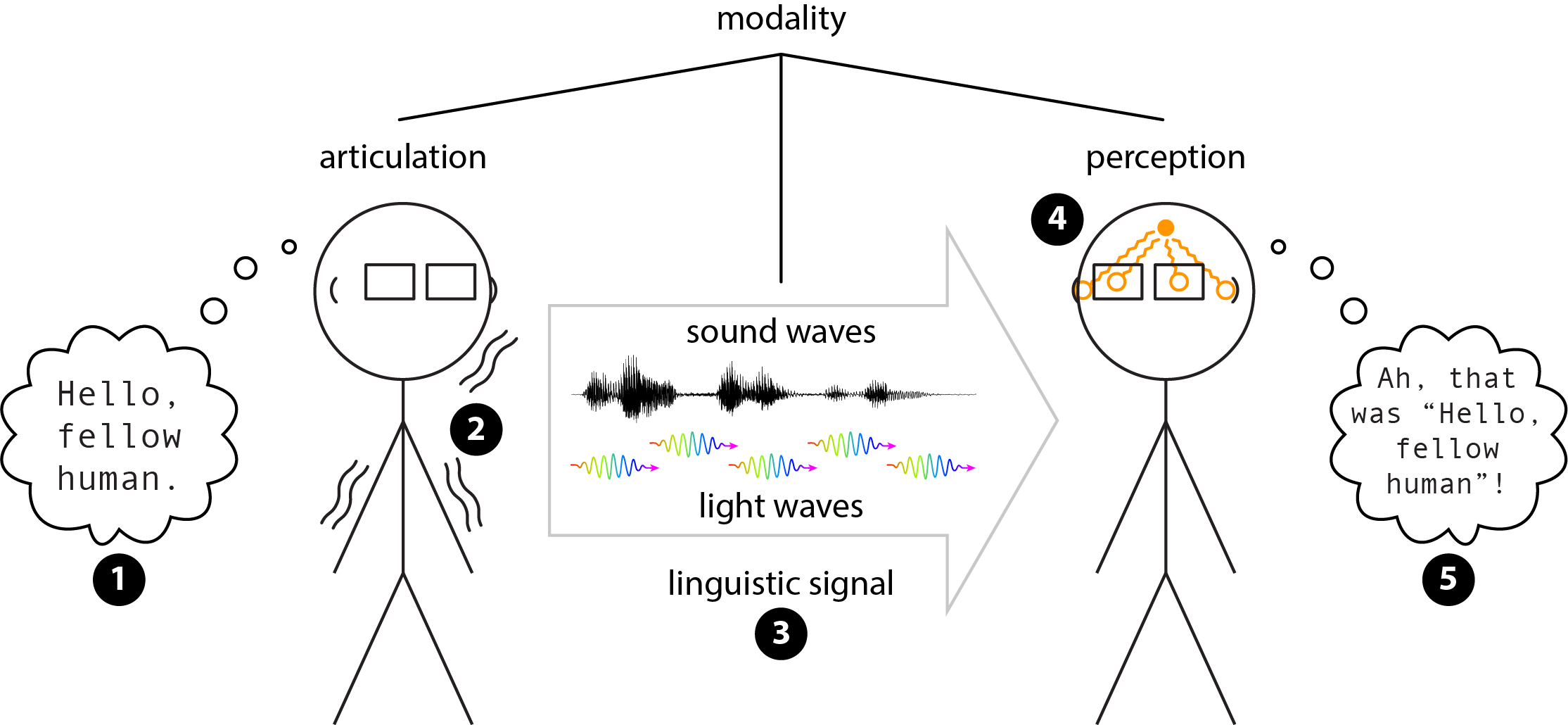

The major components of communication

An act of communication between two people typically begins with one person constructing some intended message in their mind (step ❶ in Figure 3.1). This person can then give that message physical reality through various movements and configurations of their body parts, called articulation (step ❷). Moving the body produces a physical linguistic signal (step ❸) such as sound waves (for spoken languages) or light waves (for signed languages). The linguistic signal is then received, sensed, and processed by another person’s perception (step ❹), allowing them to reconstruct the intended message (step ❺). The entire chain of physical reality from articulation to perception, is called the modality of the language.

In other words, the modality of a language is how that language is produced and perceived.

Spoken and signed languages

For spoken languages like English and Cantonese, the modality is vocal, because they are articulated with the vocal tract; acoustic, because they are transmitted by sound waves; and auditory, because they are received and processed by the hearing system. This modality is often referred to as vocal-auditory, leaving the acoustic nature of the signal implied, since that is the ordinary input to the auditory system.

Signed languages, such as American Sign Language and Chinese Sign Language, have a different modality: they are manual, because they are articulated by the hands and arms; photic, because they are transmitted by light waves; and visual, because they are received and processed by the visual system. The label for this modality is often shortened to manual-visual.

Other modalities are also possible, but we don’t discuss them in this textbook. One example is the manual-somatic modality of tactile signing. Some groups of deafblind people have adapted existing signed language in such a way that the perceiver feels the signs rather than sees them. If you’re interested you can learn more about these tactile signed languages from the readings in the Reference list at the end of this section (Checchetto et al. 2018; Edwards and Brentari 2020).

Of course, when we’re communicating we’re often using multimodal language, using more than one modality at a time (Perniss 2018, Holler and Levinson 2019, Henner and Robinson 2023). For example, spoken language is often accompanied by various kinds of co-speech behaviours: shrugging, facial expressions, and hand gestures can convey additional information like emphasis, attitude, or taking turns in a conversation, etc. (Hinnell 2020). And facial expressions convey essential meaning in many signed languages. (There are some related discussions in Chapters 8 and 10).

Terminological note: Signed languages are sometimes called sign languages. Both terms are generally acceptable, so you’ll probably encounter them both when you’re studying linguistics. For a long time, the most common term was sign languages, but recently deaf scholars have tended to use the term signed languages more frequently, to signal the parallel with spoken languages.

When we’re discussing signed languages we also need to pay attention to the word deaf. For. many years, there has been a distinction between Deaf spelled with an upper-case D and deaf with a lower-case d. The spelling difference was meant to distinguish between deafness as a physiological status and Deafness referring to a sociocultural identity. Some deaf people have argued that making that distinction leads to elitist gatekeeping within deaf communities (Kusters et al. 2017, Pudans-Smith et al. 2019).

If you’re deaf, or a user of signed languages, you and your community probably have your own preferences and norms for these terms. In this textbook, we’re going to follow the prevailing practice at the time that we’re writing, so we’ll talk about signed languages, and we won’t make a distinction in capitalization for the word deaf. If you’re not a signed language user yourself, pay attention to how the users around you are referring to their language and follow their lead.

Phonetics is the study of modality

The word phonetics is derived etymologically from the Ancient Greek word φωνή (phōnḗ), which means ‘sound’ or ‘voice’. Obviously that’s the same root for the English word phone. When I was a kid, a phone was a device that worked entirely in the vocal-auditory modality: it would transmit my voice to my friend’s ears and vice versa. These days your phone has many more functions than just transmitting voices, but we still refer to these devices as phones. In other words, etymology is not destiny!

That same evolution has happened to the term phonetics. For a long time, the field of linguistics focused almost entirely on spoken languages. Since the vocal-auditory modality has to do with sound, the study of language modality was called phonetics. These days, linguists know that all human languages have similar underlying properties, even those with different modalities. So the term phonetics now refers to the the study of linguistic modality in general, not just the vocal-auditory modality.

We also need to acknowledge, though, that many linguists still hold biased views about language and linguistics, and often forget to include signed languages and other modalities when talking about language in general and phonetics specifically. The field of linguistics is becoming more knowledgeable about linguistic diversity and more sensitive to challenges faced by marginalized groups like deaf and deafblind people. As the authors of this book, we’ve worked to be inclusive in how we talk about language, and we’ll continue to update the book as we learn more.

This chapter concentrates on articulatory phonetics, which is the study of how the body creates a linguistic signal. The other two major components of modality also have dedicated subfields of phonetics. Perceptual phonetics is the study of how the human body perceives and processes linguistic signals. We can also study the physical properties of the linguistic signal itself. For spoken languages, this is the field of acoustic phonetics, which studies linguistic sound waves. There is currently no comparable subfield that studies the physical properties of light waves for languages that use the manual-visual modality.

Check your understanding

References

Checchetto, Alessandra, Carlo Geraci, Carlo Cecchetto, and Sandro Zucchi. 2018. The language instinct in extreme circumstances: The transition to tactile Italian Sign Language (LISt) by Deafblind signers. Glossa: A Journal of General Linguistics 3(1): 66.

Edwards, Terra, and Diane Brentari. 2020. Feeling Phonology: The conventionalization of phonology in protactile communities in the United States. Language 96(4): 819–840.

Henner, Jon, and Octavian Robinson. 2023. Unsettling languages, unruly bodyminds: Imaging a Crip Linguistics. Journal of Critical Study of Communication and Disability 1(1): 7–37.

Hinnell, Jennifer. 2020. Language in the body: Multimodality in grammar and discourse. Doctoral dissertation, University of Alberta.

Holler, Judith, and Stephen C. Levinson. 2019. Multimodal language processing in human communication. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 23(8): 639–652.

Kusters, Annelies, Maartje De Meulder, and Dai O’Brien. 2017. Innovations in Deaf Studies: Critically mapping the field. In Innovations in Deaf Studies: The role of deaf scholars, ed. Annelies Kusters, Maartje De Meulder, and Dai O’Brien, Perspectives on Deafness, 1–56. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Perniss, Pamela. 2018. Why we should study multimodal language. Frontiers in Psychology 9(1109): 1–5.

Pudans-Smith, Kimberly K., Katrina R. Cue, Ju-Lee A Wolsley, and M. Diane Clark. 2019. To Deaf or not to deaf: That is the question. Psychology 10(15): 2091–2114.