14 Writing the Introductory Paragraph

The introductory and concluding paragraphs are like the top and bottom buns of a hamburger. They contain basically the same information and are critical for holding the entire piece together.

Learning Objectives

After completing the exercises in this chapter, you will be able to

- identify the three main components of an introductory paragraph

- understand how to “hook” your reader

- identify what background information needs to be included to lead to your thesis

Essay Structure

You learned in the previous chapter about Outlines that an academic paper has three main components. You can think of your essay as one big burger!

The top bun is the introduction.

The meat and vegetables in the middle are the supporting body paragraphs (several mini-burgers).

The bottom bun is the conclusion.

“Burger” by wildgica under license CC BY-NC-ND 3.0.

The top and bottom bun are both made of bread; they contain the same ingredients (or information) but look a little bit different. The “meat” of your burger is cited information in the supporting body paragraphs. This chapter focuses on the top bun: the introductory paragraph.

Structure of the Introductory Paragraph

Your introductory paragraph has three main parts:

- hook

- background information

- thesis

Hook

Start your introductory paragraph with an interesting comment or question that will get your reader interested in your topic.

Examples:

- a famous or interesting quotation

- an anecdote

- a startling fact or shocking statistic

- a statement of contrast

- a prediction

- a rhetorical question

- the definition of a critical concept

The hook is the very first thing your audience encounters. A good hook should be just one or two sentences. The goal of your hook is to introduce your reader to your broad topic in an interesting way and make your reader excited to read more.

Even though your hook is at the very beginning of your essay, you should actually write your hook LAST! It will be much easier for you to write an engaging introduction to your topic after you’ve done all of your research and after you’ve written your body paragraphs and conclusion.

Watch this video for tips on how to write a captivating and relevant hook[1]:

In part two of this video series, Mister Messinger gives some additional tips about writing hooks, explains some common mistakes that beginning writers make, and warns against using rhetorical questions: rhetorical questions, while fairly easy to write, are often poorly done and not engaging. You can watch the full Mister Messinger series on how to write an A+ paper by accessing his YouTube playlist.

Background

Your introductory paragraph should also include some background information. Don’t preview the ideas that you’ll introduce in your thesis – this is not the place to introduce your supporting points. Instead of giving your argument, explain the critical facts about your topic that an average reader needs to know in order to be prepared for your argument.

Examples of background information related to the broad topic that readers might need to know:

- brief historical timeline of critical events

- laws or regulations

- definitions

- current status

The information that you need to provide depends heavily on your topic:

- If you are arguing in favour of changing drinking and driving laws, your background information might explain what the current laws are.

- If you are arguing that stem cell research should be more heavily supported by the government, you should explain what the current status of stem cell research is.

- If you are arguing that culture is learned and not inherited, you might start by defining what “culture” is.

Remember that you are writing for a general audience. Don’t assume that your reader has specialized knowledge of your topic.

Remember that you are writing for a general audience, so you shouldn’t assume that your readers have any specific knowledge of your topic or that they know any specialized terminology. The background information that you provide should give your readers the information they need to understand the argument in your thesis. Be sure, though, that you don’t *preview* the thesis. Do not include your argument or any information related to your body paragraphs as background information.

Watch this video for more information about how to include relevant background information[2]:

Remember, you can watch the full Mister Messinger series on how to write an A+ paper by accessing his YouTube playlist.

Thesis

As you know, the thesis is the most important sentence in your essay. It is placed last in the introductory paragraph. The hook and the background information should lead gracefully to the thesis. The thesis concisely states the answer to your research question by stating the specific topic, implying your stance on the topic, and listing the topics of the supporting body paragraphs.

Learning Check

Consider this short introductory paragraph and answer the questions that follow:

Sample Introductory Paragraph

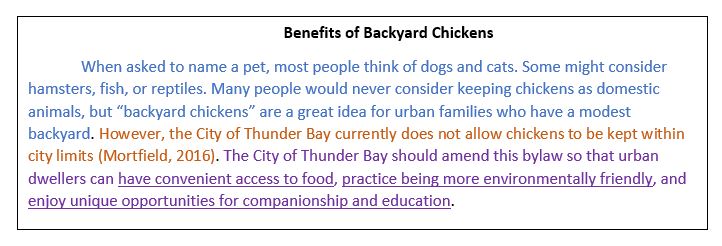

Let’s look at this introductory paragraph that was created by a student for her essay on why the City of Thunder Bay should change its existing laws to allow residents to raise chickens.

The writer’s hook is in blue text. The writer is trying to engage the reader on the topic by providing a surprising contrast. What other hooks could the writer have used instead?

The background information is in orange text. The writer realized that her readers wouldn’t be able to understand her point of view if they didn’t know that the law currently forbids city residents from raising chickens on their property. Is this enough background information for you to understand the thesis? What additional information could the writer have provided?

The thesis is in purple text. The thesis statement is well-written and clearly states all necessary information:

- The specific topic (the ‘chicken bylaw’ in Thunder Bay)

- The writer’s stance (the bylaw should be changed to allow raising chickens within city limits)

- The reasons for the writer’s stance (the underlined clauses in the thesis)

When the writer drafts her body paragraphs, she needs to make sure that each underlined idea is the topic of a paragraph and that those paragraphs are organized in the same order as the ideas are presented in the thesis.

- Mister Messinger. (2020, July 7). Part 1: Discover how to start essay with an A+ hook: STRONG attention grabbing examples [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yvrnVHd-oyM ↵

- Mister Messinger. (2020, August 6). How to start an essay: Add background information to write a strong introduction [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-bd1t2u-HbE&t=223s ↵