4 Culture “Shock”

Learning Objectives

After completing this chapter, you will be able to

- define ethnocentrism, culture shock and cultural relativism

- understand the causes of culture shock

- describe the stages of cultural adaptation

- recognize common symptoms of culture shock

- critique the standard U-shaped model of cultural adaptation and the term “culture shock”

- list the five key areas of transition stress

- define Seasonal Affective Disorder

Ethnocentrism, Culture Shock, and Cultural Relativism

Information in this section has been adapted from Chapter 3.1: What is Culture in Introduction to Sociology – 2nd Canadian Edition by William Little[1], which is made available by OpenStax College and BCcampus Open Education under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

Despite how much humans have in common, cultural differences are far more prevalent than cultural universals. For example, while all cultures have language, analysis of particular language structures and conversational etiquette reveals tremendous differences. In some Middle Eastern cultures, it is common to stand close to others in conversation. North Americans keep more distance, maintaining a large personal space. Even something as simple as eating and drinking varies greatly from culture to culture. If your professor comes into an early morning class holding a mug of liquid, what do you assume she is drinking? In Canada, it’s most likely filled with coffee, not Earl Grey tea, a favourite in England, or yak butter tea, a staple in Tibet.

The way cuisines vary across cultures fascinates many people. Some travelers, like celebrated food writer Anthony Bourdain, pride themselves on their willingness to try unfamiliar foods, while others return home expressing gratitude for their native culture’s cuisine. Canadians might express disgust at other cultures’ cuisine, thinking it is gross to eat meat from a dog or guinea pig for example, while they do not question their own habit of eating cows or pigs. Such attitudes are an example of ethnocentrism, or evaluating and judging another culture based on how it compares to one’s own cultural norms. Ethnocentrism, as sociologist William Graham Sumner (1840-1910) described the term, involves a belief or attitude that one’s own culture is better than all others (1906). Almost everyone is a little bit ethnocentric. For example, Canadians tend to say that people from England drive on the “wrong” side of the road, rather than the “other” side.

A high level of appreciation for one’s own culture can be healthy; a shared sense of community pride, for example, connects people in a society. But ethnocentrism can lead to disdain or dislike for other cultures, causing misunderstanding and conflict. People with the best intentions sometimes travel to a society to “help” its people, seeing them as uneducated or backward, essentially inferior. In reality, these travelers are guilty of cultural imperialism — the deliberate imposition of one’s own cultural values on another culture. Europe’s colonial expansion, begun in the 16th century, was often accompanied by a severe cultural imperialism. European colonizers often viewed the people in the lands they colonized as uncultured savages who were in need of European governance, dress, religion, and other cultural practices. On the West Coast of Canada, the Aboriginal potlatch (gift-giving) ceremony was made illegal in 1885 because it was thought to prevent Aboriginal peoples from acquiring the proper industriousness and respect for material goods required by civilization. A more modern example of cultural imperialism may include the work of international aid agencies who introduce modern technological agricultural methods and plant species from developed countries while overlooking indigenous varieties and agricultural approaches that are better suited to the particular region.

Culture shock may appear because people are not always expecting cultural differences. Anthropologist Ken Barger discovered this when conducting participatory observation in an Inuit community in the Canadian Arctic (1971). Originally from Indiana, Barger hesitated when invited to join a local snowshoe race. He knew he’d never hold his own against these experts. Sure enough, he finished last, to his mortification. But the tribal members congratulated him, saying, “You really tried!” In Barger’s own culture, he had learned to value victory. To the Inuit people winning was enjoyable, but their culture valued survival skills essential to their environment: How hard someone tried could mean the difference between life and death. Over the course of his stay, Barger participated in caribou hunts, learned how to take shelter in winter storms, and sometimes went days with little or no food to share among tribal members. Trying hard and working together, two nonmaterial values, were indeed much more important than winning.

During his time with the Inuit, Barger learned to engage in cultural relativism. Cultural relativism is the practice of assessing a culture by its own standards rather than viewing it through the lens of one’s own culture. The anthropologist Ruth Benedict (1887–1948) argued that each culture has an internally consistent pattern of thought and action, which alone could be the basis for judging the merits and morality of the culture’s practices. Cultural relativism requires an open mind and a willingness to consider, and even adapt to, new values and norms. The logic of cultural relativism is at the basis of contemporary policies of multiculturalism. However, indiscriminately embracing everything about a new culture is not always possible. Even the most culturally relativist people from egalitarian societies, such as Canada — societies in which women have political rights and control over their own bodies — would question whether the widespread practice of female genital circumcision in countries such as Ethiopia and Sudan should be accepted as a part of a cultural tradition.

Sometimes when people attempt to rectify feelings of ethnocentrism and develop cultural relativism, they swing too far to the other end of the spectrum. Xenocentrism is the opposite of ethnocentrism, and refers to the belief that another culture is superior to one’s own. In fact, the Greek root word xeno, pronounced “ZEE-no,” means “stranger” or “foreign guest”. An exchange student who goes home after a semester abroad or a sociologist who returns from the field may find it difficult to associate with the values of their own culture after having experienced what they deem a more upright or nobler way of living.

Sociologists attempting to engage in cultural relativism may struggle to reconcile aspects of their own culture with aspects of a culture they are studying. Pride in one’s own culture does not have to lead to imposing its values on others. Nor does an appreciation for another culture preclude individuals from studying it with a critical eye. In the case of female genital circumcision, a universal right to life and liberty of the person conflicts with the neutral stance of cultural relativism. It is not necessarily ethnocentric to be critical of practices that violate universal standards of human dignity that are contained in the cultural codes of all cultures, (while not necessarily followed in practice). Not every practice can be regarded as culturally relative. Cultural traditions are not immune from power imbalances and liberation movements that seek to correct them.

Cultural Adaptation Cycle (aka Culture Shock)

When people think of the cultural adaptation cycle, most people think of “culture shock,” which is really just one stage in the cycle. People experience “culture shock” when they encounter a culture that has significantly different beliefs, customs, behaviors, values, or norms from their own. Culture shock is a perfectly normal, emotional reaction that may include feelings of depression, anxiety, or disorientation and that may even manifest itself physically by affecting an individual’s health or their sleeping or eating habits.

The U-Shape Model of the Stages of Culture Shock

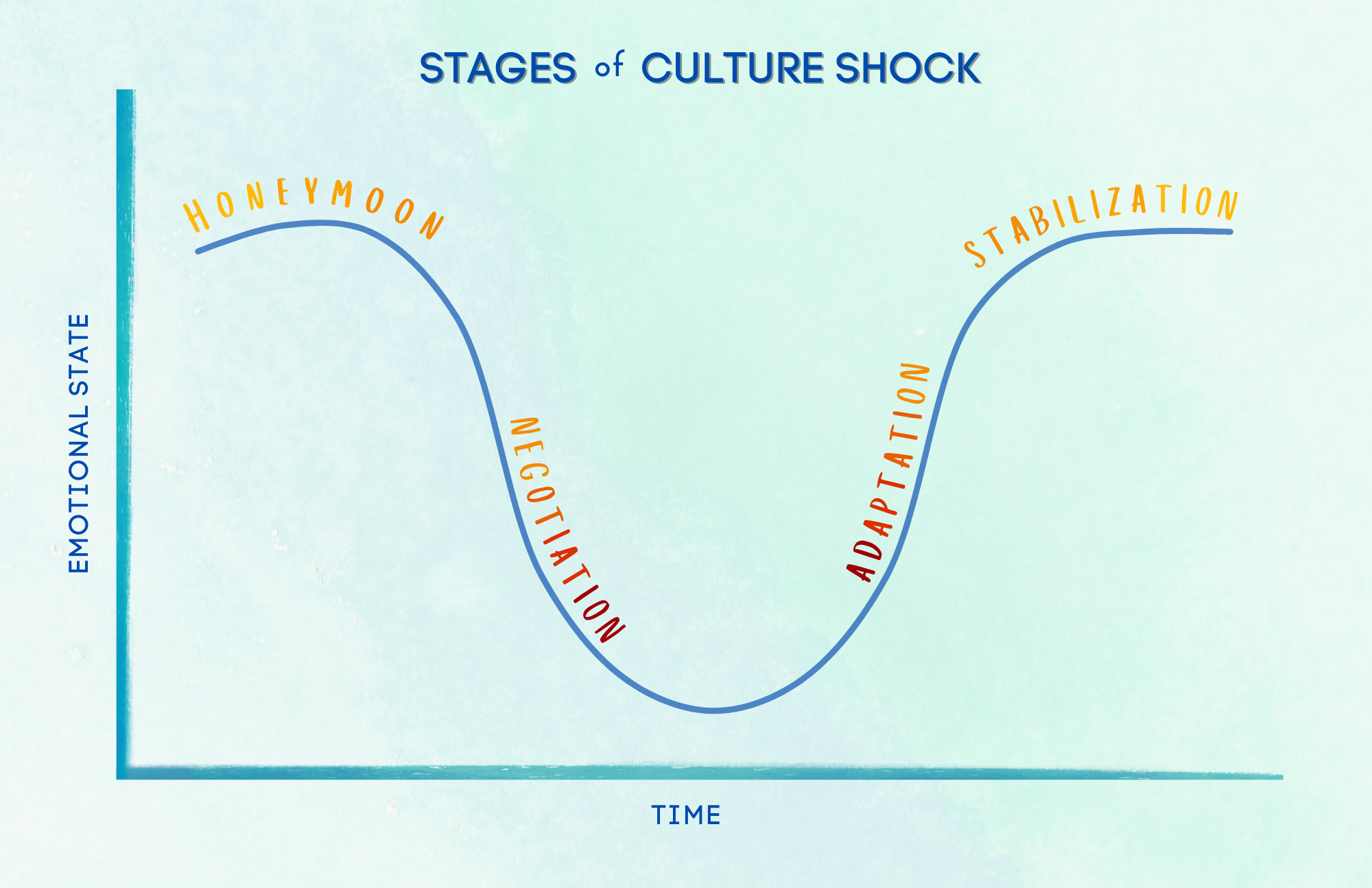

Many people have seen diagrams of culture shock that look like this[2]:

In the initial honeymoon stage, the cultural newcomer is in love with their new surroundings. The host culture seems ideal. Every interaction and experience in the host culture is exciting and interesting.

In stage two, reality sets in. In the negotiation (or “slump”) stage, the cultural newcomer starts to experience difficulties in the host culture. They may compare the host culture with their home culture and may judge the new culture harshly. This is the stage we most commonly associate with the term “culture shock”. Culture shock can manifest itself in both physically and psychologically. People suffering from culture shock may experience general and unexplained exhaustion. They may sleep far more than what is normal for them, or they may have insomnia and be unable to sleep. They may overeat or eat much less than they normally would and might gain or lose weight as a result. They might overindulge in alcohol or experiment with other risky behaviour that is out of the ordinary for them. They may be more concerned than usual about getting ill and may notice minor aches, pains and cold symptoms more than they normally would and may in fact experience more colds and stomach aches than normal. They may experience feelings of stress, anxiety, and depression. They may withdraw from social events and feel lonely and homesick.

In stage three, the adjustment or realization stage, the newcomer starts to adapt to the new culture. They begin to gain a deeper understanding of the host culture and become more competent at performing basic tasks, like getting groceries and using public transportation, and start to feel more at home in the new culture.

The final stage in this model, the stabilization or adaptation stage, assumes that the cultural newcomer becomes fully acculturated to the host culture. The cultural newcomer has fully adapted to the host culture.

This short video[3] describes each stage in more detail and provides tips on how to achieve cultural adaptation:

Issues with the U-Shaped Model

Some researchers argue that the U-shaped model is deeply flawed and overly simplistic. The concept of the “adjustment” phase is especially problematic.

Hofstede[4], notes that the fourth stage is not the same for everyone. While some cultural newcomers will stabilize, or adapt, to the host cultures, some will reject the host culture and some will assimilate to the host culture.

If a cultural newcomer adapts, they have achieved a kind of cultural hybridity. They are bicultural in that they have developed a new cultural identity in addition to their original cultural identity, and they can access these different identities to function in different cultural situations.

If a newcomer rejects the host culture, they have failed to adapt. They may spend most of their time with people of their own culture and will avoid interacting with locals and experiencing local food or other customs. They have no desire to “fit in” with the host culture. They may feel quite negatively toward the host culture and may choose to return home.

On the other hand, the newcomer may completely assimilate to the host culture. In this case, they feel themselves to be a member of the host culture and this new cultural identity almost supersedes their original cultural identity. They can speak the language and have adopted local mannerisms. They may even feel disdain for their home culture and may feel superior to other cultural newcomers.

The issues, then, with the model is that not everyone will experience the stages in the order the model suggests and not everyone will experience all stages in the same way. The model may actually exacerbate feelings of stress and unhappiness by creating unrealistic expectations about the adaptation process.

Transition Stress

Other researchers[5] complain the term “culture shock” has become a bit of a meaningless buzzword founded on an ethnocentric assumption that cultural differences are inherently strange and will result in discomfort. It also implies a sudden change rather than a gradual process and doesn’t capture the complexity of cross-cultural transitions.

Many researchers prefer the term “transition stress” as it reinforces the idea that there are a variety of ways that adjustment challenges may present themselves when an individual has moved from their home culture to a host culture. These adjustment challenges may result in stress not simply because the individual has encountered a new culture; rather, because of the experience of the culture, the individual may be experiencing identify shifts, role changes, small difficulties and confusion in completing normal daily tasks, competing emotions of excitement and trepidation, an inability to understand the actions and viewpoints of others, and a mentally draining re-evaluation of existing values, behaviours and worldviews.

To learn more about “transition stress,” read this short article in Psychology Today: https://www.psychologytoday.com/ca/blog/between-cultures/201603/understanding-transition-stress

The level of stress and types of stress triggers will depend on why the individual has changed cultures; for example, if a person has relocated for employment, they may experience stress related to acclimating to a new work environment and may also need to manage conflicting loyalties to their home office and their new office. Students may experience difficulties adjusting to different academic standards and workloads and may also have additional emotional challenges as they strive to maintain relationships with friends and family in their home country while simultaneously trying to become part of a new social circle. The U-shaped model also does not consider other important factors, including gender, age, situational differences, or the length of the sojourn. Certainly a tourist, a refugee and an international student will all have different experiences of culture shock.

The other issue with the U-Shaped model is that does not explain how or why adjustment challenges occur, and it seems to assume a correlation between adjustment and emotional happiness.

Seasonal Challenges

As part of adjusting to a new culture, people may experience emotional ups and downs that go beyond homesickness or cultural confusion. In some cases, these feelings may be linked to Seasonal Affective Disorder (SAD), a type of depression that occurs at certain times of the year — most commonly in the fall and winter, when there is less sunlight. SAD can affect mood, energy, sleep patterns, and concentration. While anyone can experience SAD, people who have moved from a warm, sunny climate to a region with long, dark winters (like Canada) may be especially vulnerable.

Because the symptoms of SAD — such as tiredness, low mood, and difficulty focusing — can overlap with symptoms of culture shock or academic stress, it may not be immediately obvious what’s causing the problem. Recognizing the signs of SAD is important so that you can seek support. Light therapy, vitamin D, exercise, counseling, and time outdoors are common strategies for managing symptoms. If you’re feeling down and can’t figure out why, it might not just be culture shock — it could be your body reacting to seasonal changes in light.

Discussion

Consider what you’ve learned about culture shock.

- How might you identify if a classmate has culture shock?

- If you think you or someone you know is suffering from culture shock, what should you do?

- How can you avoid, or at least alleviate, some of the negative aspects of culture shock?

- Which “transition” in your move abroad will be the most difficult for you to cope with?

Cultural Adaptation

In this presentation[6], an Indian student studying in Finland describes her acculturation journey:

Discussion

How has this student’s experiences been similar to or different from your own?

Additional Resources

As cited by Little:

Barger, K. (2008). “Ethnocentrism.” Indiana University. Retrieved from http://www.iupui.edu/~anthkb/ethnocen.htm.

Barthes, R. (1977). “Rhetoric of the image.” In, Image, music, text (pp. 32-51). New York, NY: Hill and Wang.

Berger, P. (1967). The sacred canopy: Elements of a theory of religion. New York, NY: Doubleday.

Darwin, C. R. (1871). The descent of man, and selection in relation to sex. London, UK: John Murray.

DuBois, C. (1951, November 28). Culture shock [Presentation to panel discussion at the First Midwest Regional Meeting of the Institute of International Education. Also presented to the Women’s Club of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, August 3, 1954].

Fritz, T., Jentschke, S., Gosselin, N., Sammler, D., Peretz, I., Turner, R., . . . Koelsch, S. (2009). Universal recognition of three basic emotions in music. Current Biology, 19(7). doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.02.058.

Kymlicka, W. (2012). Multiculturalism: Success, failure, and the future. [PDF] Migration Policy Institute. Retrieved from http://www.upf.edu/dcpis/_pdf/2011-2012/forum/kymlicka.pdf.

Murdock, G. P. (1949). Social structure. New York, NY: Macmillan.

Oberg, K. (1960). Cultural shock: Adjustment to new cultural environments. Practical Anthropology, 7, 177–182.

Smith, D. (1987). The everyday world as problematic: A feminist sociology. Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press.

Sumner, W. G. (1906). Folkways: A study of the sociological importance of usages, manners, customs, mores, and morals. New York, NY: Ginn and Co.

Suggestions for additional reading:

Gilmore, K. (2016, November 3). Why we need to embrace culture shock – Kistofer Gilmour – TEDxTownsville [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rGSD6jduFJg.

Grothe, T. (2022, May 17). 6.2: Managing culture shock. In Exploring intercultural communication. LibreTexts Project. https://socialsci.libretexts.org/Courses/Butte_College/Exploring_Intercultural_Communication_(Grothe)/06%3A_Culture_Shock/6.02%3A_Managing_Culture_Shock

Saphiere, D. H. (2014, August 12). The nasty (and noble) truth about culture shock – and ten tips for alleviating it. Cultural Detective Blog. https://blog.culturaldetective.com/2014/08/12/the-nasty-and-noble-truth-about-culture-shock/.

- Little, W. (2016, October 5). Chapter 3: Culture. In Introduction to sociology (2nd Canadian ed.). BCcampus Open Education. https://opentextbc.ca/introductiontosociology2ndedition/chapter/chapter-3-culture/↵ ↵

- Veillieux, H. (2022, April 12). StagesOfCultureShock-graph_v2 [Digital Image]. Confederation College. https://bit.ly/3jylwLF. CC BY 4.0. ↵

- The Global Society. (2019, August 27). Culture shock and the cultural adaptation cycle: What it is and what to do about it [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=g-ef-xhC_bU. ↵

- Hofstede, Hofstede, G. J., & Minkov, M. (2010). Cultures and organizations : Software of the mind (3rd ed.). McGraw-Hill. ↵

- Berardo, K., & Deardorff, D. K. (2012). Building cultural competence : Innovative activities and models. Stylus Pub. ↵

- Student Talks. (2017, November 13). The process of cultural adaptation - Priyanka Banerjee [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=diPmFgSNENY. ↵