35 Direct Routine Messages

Learning Objectives

After completing this chapter, you will be able to

- explain the three-part structure of a direct writing plan and know when to use it

- identify different types of routine messages

- identify the key elements of routine messages that use the direct approach

- format messages effectively using lists to give routine information and instructions

Routine messages include emails, memos, and letters that give information or make requests. For routine messages, you should use plain language and a direct approach. As Canada is a relatively low-context country, a direct writing approach is often standard for routine messages.

The Direct Approach

The direct approach “frontloads the main point, which means getting right to the point in the first or second sentence of the opening paragraph. The direct approach is used when you expect the audience to be pleased, mildly interested or have a neutral response to the message” (Vance, n.d.[1]). Positive, day-to-day, and routine messages use the direct organizing pattern. Remember that this approach is likely not appropriate for a message that contains bad news that might be upsetting or surprising to your reader.

Getting to the main idea first saves the reader time and reduces frustration by immediately clarifying the purpose of communication. Frontloading a message also accommodates the reader’s capacity for remembering what they see first, as well as respects their time in achieving the goal of communication, which is understanding the writer’s point.

Since most business messages have a positive or neutral effect on the reader, business writers should become very familiar with this three-part structure for a direct message:

Opening: Get the reader’s attention by delivering the main message first. Answer your reader’s most important questions; state the good news; make a direct, specific request; or provide the most important information.

Middle: Explain details of the news or inquiry and supply background and clarification when needed. If there are further points or questions, they are presented in parallel form in a bulleted or numbered list (maximum five or six items). If you need to provide an explanation or rationale for a request, that information should be in the middle section as well, not in the opening.

Closing: End pleasantly in one or more of the following ways: provide contact information; ask for action, input, or a response, often by a deadline; tell the reader what happens next; communicate goodwill by showing appreciation, restating reader benefits, or expressing hope for a continuing relationship.

Direct-approach messages are the norm in North America for routine messages, but not every culture responds to direct correspondence in exactly the same way. In high-context cultures — such as those in China, Japan, and Arab nations— directness is considered rude. In such cases, it is important to establish rapport before citing a problem or making a request and even then to suggest or ask rather than demand. In Japan, where formality is important, it is customary to embed a request and to soften it with preliminaries and other politeness strategies. On the other hand, people in Western cultures consider a lack of directness to be a waste of their time. When you are communicating cross-culturally, weigh your reader’s tolerance for directness before you launch into your request or response.

Types of Routine Messages

Routine messages might provide information or instructions or request that the receiver provides information or performs a task. Routine messages might also be responses to a routine request for information or action. Review the examples below to see how the direct approach can be used to structure these types of routine messages.

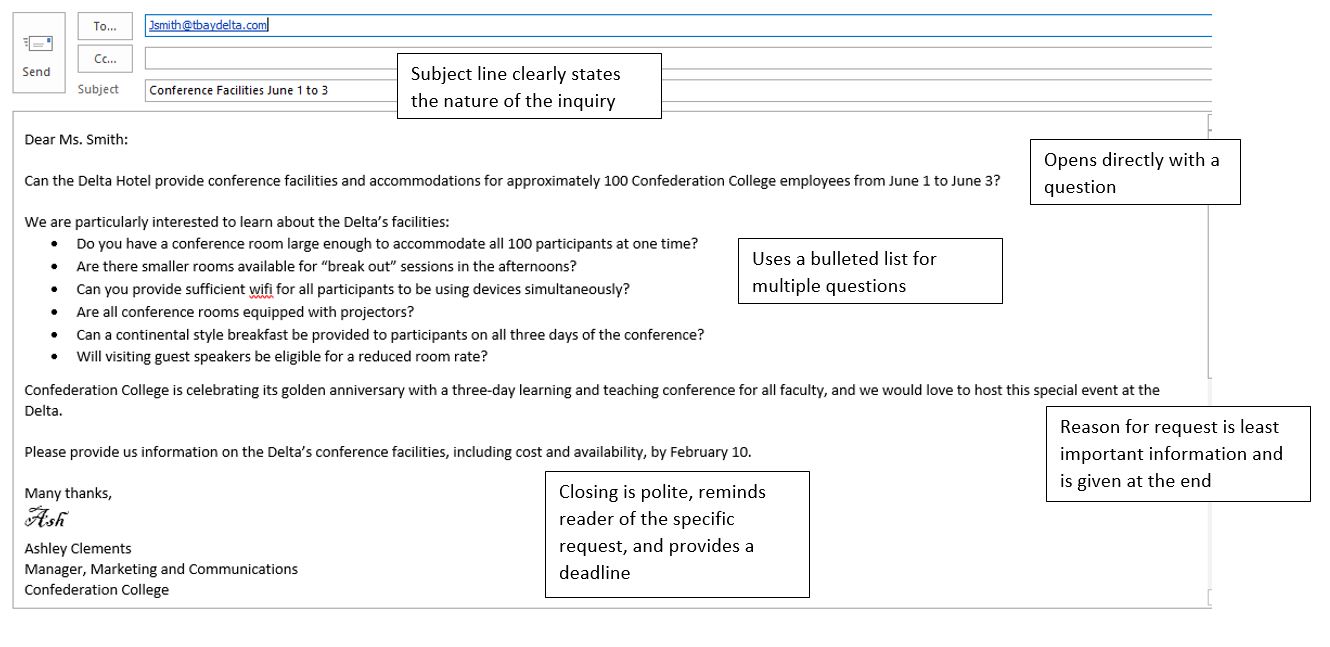

Make Routine Requests and Respond to Requests

Use the direct writing approach to make and respond to routine requests for information or action.

To write an effective request,

- put the main idea (your request) first

- phrase your request as a question (eg How much is...) or as a polite command using please + an action verb (eg Please call…)

- use a bulleted list for multiple requests or questions

- give a reason for the request or state its benefit after you’ve made your request

- omit unnecessary details

- close in a courteous and efficient way.

To write an effective response to a request for information or action, first determine if a response is necessary and, if it is, decide if you are the best person to respond to the request. If the message was sent to the entire company, the sender would be overwhelmed if everyone wrote back to say thanks. Also check to see who you should respond to; if the message was sent to multiple people, is it appropriate to ‘reply all’ or should you reply just to the sender.

To write an effective response,

- reply as soon as you can

- keep the original subject line (unless the focus on the message has changed significantly)

- begin with the good news or most important piece of information

- avoid unnecessary phrases (I am writing to respond to your email….)

- use formatting like bulleted lists or charts to respond to multiple requests or questions

- provide information in the same order as it was requested

- anticipate and provide additional information that your reader might need

Learning Check

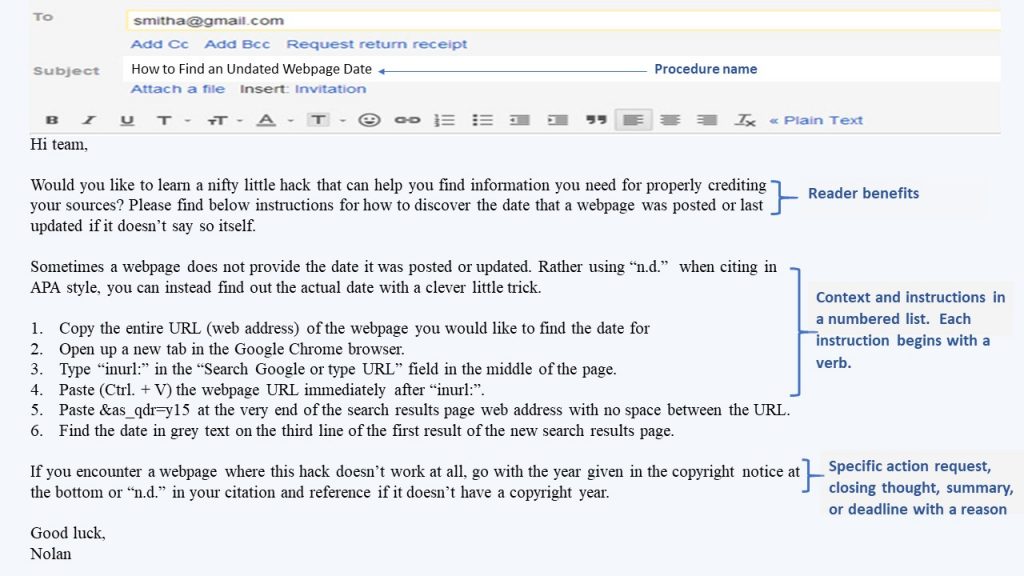

Provide Instructions or Information

The examples and explanations below are adapted from Unit 24: Information Shares, Action Requests, and Replies in Communication at Work by Karen Vance (Kwantlen Polytechnic University[2], made available by Pressbooks under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license

Effective organization and style are critical in requests for action that contain detailed instructions. Whether you’re explaining how to operate equipment, apply for funding, renew a membership, or submit a payment, the recipient’s success depends on the quality of the instruction. Vagueness and a lack of detail can result in confusion, mistakes, and requests for clarification. Too much detail can result in frustration, skimming, and possibly missing key information. Profiling the audience and gauging their level of knowledge is key to providing the appropriate level of detail for the desired results.

Look at any procedures document and you’ll see that the quality of its readability depends on the instructions being organized in a numbered list of parallel imperative sentences. Imperative sentences drop the subject (the doer of the action, which is assumed to be the reader in the case of instructions) and start instead with an action-oriented verb. In the example below, for instance, the reader can easily follow the directions because each of the six main steps begins with a simple verb describing a common computer operation: Copy, Open, Type, Paste (twice), and Find.

If you begin any imperative sentence with a prepositional (or other) phrase to establish some context for the action first (such as this imperative sentence does), move the adverb after the verb and the phrase to the end of the sentence. (If the previous sentence followed its own advice, it would look like this: Move the adverb after the verb and the phrase to the end of the imperative sentence if you begin it with a prepositional (or other) phrase to establish some context for the action first.) Finally, surround the list with a proper introduction and closing as shown below.

Though helpful on its own, the above message would be much improved if it included illustrative screenshots at each step. Making a short video of the procedure, posting it to YouTube, and adding the link to the message would be even more effective.

Combining DOs and DON’Ts is an effective way to help your audience complete the instructed task without making common rookie mistakes. Always begin with the DOs after explaining the benefits or rewards of following a procedure, not with threats and heavy-handed ‘Thou shalt nots”. You can certainly follow up with helpful DON’Ts and consequences if necessary, but phrased in courteous language, such as “please remember to exercise caution in construction areas.”

Elements of Clear Instructions

To write clear instructions,

- Begin with a statement that clearly explains what the reader will accomplish after following the instructions

- Use a numbered list for procedures that must be completed in sequence (for example, a step-by-step guide to using a new technology)

- Use bullet points when listing elements that do not need to be considered in a specific order (for example, a list of items to bring to a work convention)

- Arrange each step in the order it should be completed (chronological) or in order of importance

- Ensure your list contains only ONE instruction per line

- Start each instruction with an action verb in the imperative (command) mood to ensure you have good parallel structure

- Describe reader benefits at the end especially if you are encouraging your reader to use the process/procedure that you are explaining.

Consider the example below of clearly stated instructions.

Setting up your new GTD webcam involves only a few steps:

- Plug the webcam into your computer’s USB port.

- Follow the installation prompts on your screen.

- Restart your computer.

- Open any application that uses your webcam.

- Perform a test to ensure your webcam is positioned correctly.

- Add a background filter to blur the room behind you.

After you’ve completed these five steps, you can begin using your webcam to communicate professionally in virtual meetings.

Notice that the message is divided into three clear parts:

- A direct lead-in that explains the content of the message (to explain how to set up a webcam).

- A list of clear instructions, in parallel form and starting with a strong verb that clearly indicates what the reader should do.

- A closing statement that provides a sense of goodwill and describes why the reader should want to follow the instructions.

For more information about how to format a list, see the Lists chapter of this book.

Learning Check

Additional Resources

As cited by Vance:

Gatbondon, G. (2019). Chapter 8: Writing routine and positive messages (MG206) [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uFUsqgqIMXY

Gregg Learning. (2019). How to write instructions for business [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kIiQcQVr9H0

Smith, C. L. (2015, May 8). Canada: When does an email form a legally-binding agreement? Ask the Canucks. Retrieved from http://www.mondaq.com/canada/x/395584/Contract+Law/When+Does+An+Email+Form+A+LegallyBinding+Agreement+Ask+The+Canucks

- Vance, K. (n.d.). Unit 11: Choosing an organizational structure. In Communication at work (adapted for KPU from Jordan Smith's (n.d.) Communication @ work). https://kpu.pressbooks.pub/communicationsatwork/ CC By 4.0 license ↵

- Vance, K. (n.d.). Communication at work (adapted for KPU from Jordan Smith's (n.d.) Communication @ work). https://kpu.pressbooks.pub/communicationsatwork/ CC By 4.0 license ↵