12 Researching and Evaluating Beyond CRAAP

Learning Objectives

After completing this chapter, you will be able to

- Use fact-checking websites to verify information

- Search for the original source of reported information

- Use third party information to determine if an online source is reputable

Information in this section has been adapted from Web Literacy for Student Fact-Checkers by Michael A. Caulfield[1] which is made available by under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License except where otherwise noted.

The “CRAAP” method of evaluating a source can be a good starting point, but it isn’t always ideal. Some of the criteria that you look for in CRAAP can be easy to fake or are actually somewhat meaningless. For example, .orgs are not always better sources of information than .coms, and fewer ads on a page doesn’t necessarily mean that the page is more credible than one with paid advertising.

In this video, Michael Caulfield[2] shows us how easy it is to be fooled into thinking an online source is “CRAAP” when it is really “crap”:

To really know if a source is credible, you need to fact check the information, find the original source of that information, and use search techniques to determine if the source is reputable.

Step 1: Fact Check

When fact-checking a particular claim, quote, or article, the simplest thing you can do is to see if someone has already done the work for you, so start by seeing if sites like Politifact, or Snopes, or even Wikipedia have already researched the claim.

This doesn’t mean you should blindly accept the word of the fact-checking site, but a reputable fact-checking site or subject wiki will have done much of the leg work for you: tracing claims to their source, identifying the owners of various sites, and linking to reputable sources for counterclaims. And that legwork, no matter what the finding, is probably worth ten times your intuition. If the claims and the evidence they present ring true to you, or if you have built up a high degree of trust in the site, then you can treat the question as closed. But even if you aren’t satisfied, you can start your work from where they left off.

Reputable Fact-Checking Websites

The following organizations are generally regarded as reputable fact-checking organizations:

- AFP Fact Check (https://factcheck.afp.com/afp-canada) (Canada)

- Politifact (Politifact.com) (USA)

- Fact Check (Factcheck.org) (USA)

- Washington Post Fact Checker (https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/fact-checker) (USA)

- Snopes (Snopes.com) (USA)

- NPR Fact Check (https://www.npr.org/sections/politics-fact-check) (USA)

- Guardian Reality Check (https://www.theguardian.com/news/reality-check) (UK)

- BBC Reality Check (https://www.bbc.com/news/reality_check) (UK)

- Channel 4 Fact Check (https://www.channel4.com/news/factcheck/) (UK)

- Full Fact (https://fullfact.org/) (UK)

How to Create a Search Query for Fact Checking Sites

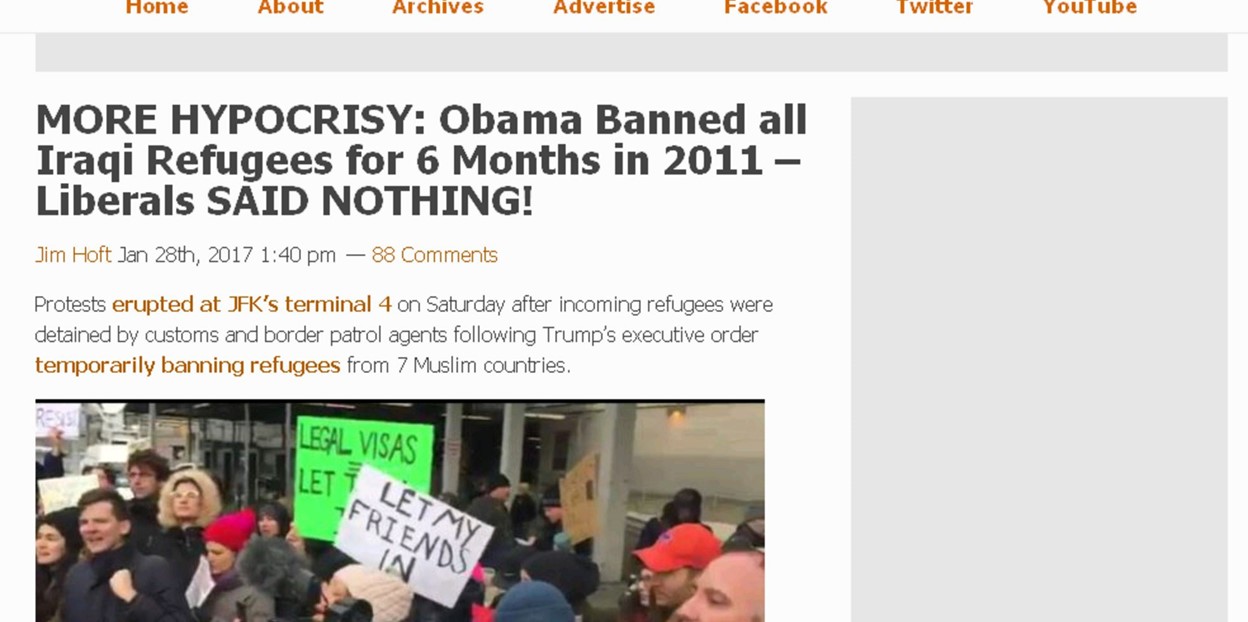

You can find previous fact-checking by using the “site” option in Google to search known and trusted fact-checking sites for a given phrase or keyword. For example, if you see this story,

then you might use enter this query into google: Obama Iraqi refugee ban 2011 site:snopes.com

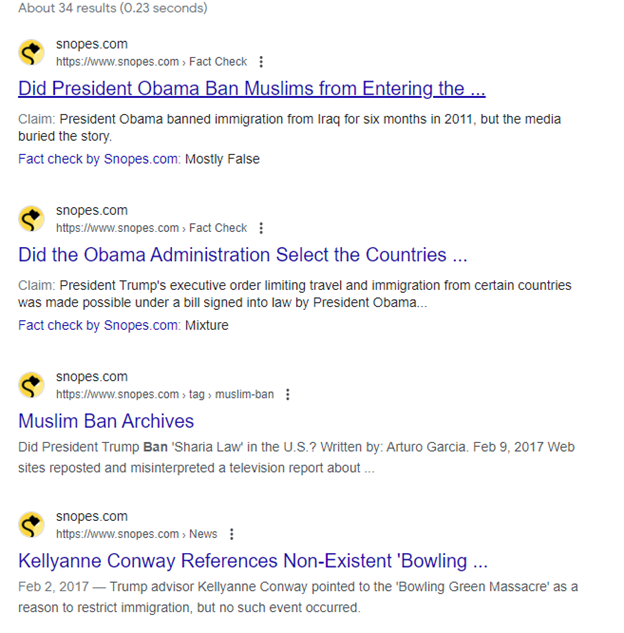

Here are the results of our search:

You can see the search here. The results show that work has already been done in this area. In fact, the first result from Snopes answers our question almost fully. Remember to follow best search engine practice: scan the results and focus on the URLs and the blurbs to find the best result to answer your query.

To fact check the fact checker, you can repeat the process with a different fact checking site: obama iraq refugee ban 2011 site:politifact.com

The results show that the site Politifact has also checked this claim. You can now compare the Snopes and Politifact analyses to see if both organizations agree about the level of truth in President Trump’s claim about President Obama.

Step 2: Go Upstream to Find the Origins of the Information

If you can’t find previous work on the claim, start by trying to trace the claim to the source. If the claim is about research, try to find the journal it appeared in. If the claim is about an event, you need to “go upstream” to try to find the news publication in which it was originally reported.

Consider this claim on the conservative site the Blaze:

Is this claim true?

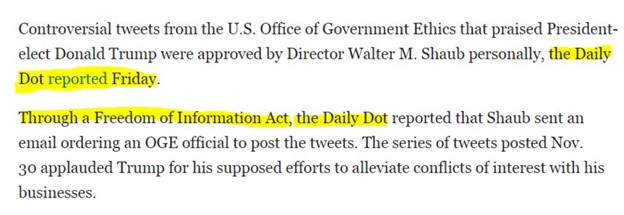

Of course we can check the credibility of this article by considering the author, the site, and when it was last revised. We’ll do some of that, eventually. But it would be ridiculous to do it on this page. Why? Because like most news pages on the web, this one provides no original information. It’s just a rewrite of an upstream page. We see the indication of that here:

All the information here has been collected, fact-checked (we hope!), and written up by the Daily Dot. It’s what we call “reporting on reporting.” There’s no point in evaluating the Blaze’s page; we need to “go upstream” to the original story and evaluate that story. When you get to the Daily Dot, then you can start asking questions about the site or the source. And it may be that for some of the information in the Daily Dot article you’d want to go a step further back and check their primary sources. But you have to start there, not here.

In the Blaze story example, it was straightforward to find the source of the content. The Blaze story clearly links to the Daily Dot piece so that anyone reading their summary is one click away from confirming it with the source, so checking the credibility of the source is readily available to you.

This is good internet citizenship. Articles on the web that repurpose other information or artifacts should state their sources, and, if appropriate, link to them. This matters to creators because they deserve credit for their work. But it also matters to readers who need to check the credibility of the original sources.

How to Find the Original Source when the Source isn’t Linked

Unfortunately, many people on the web are not good citizens. This is particularly true with material that spreads quickly as hundreds or thousands of people share it–so-called “viral” content.

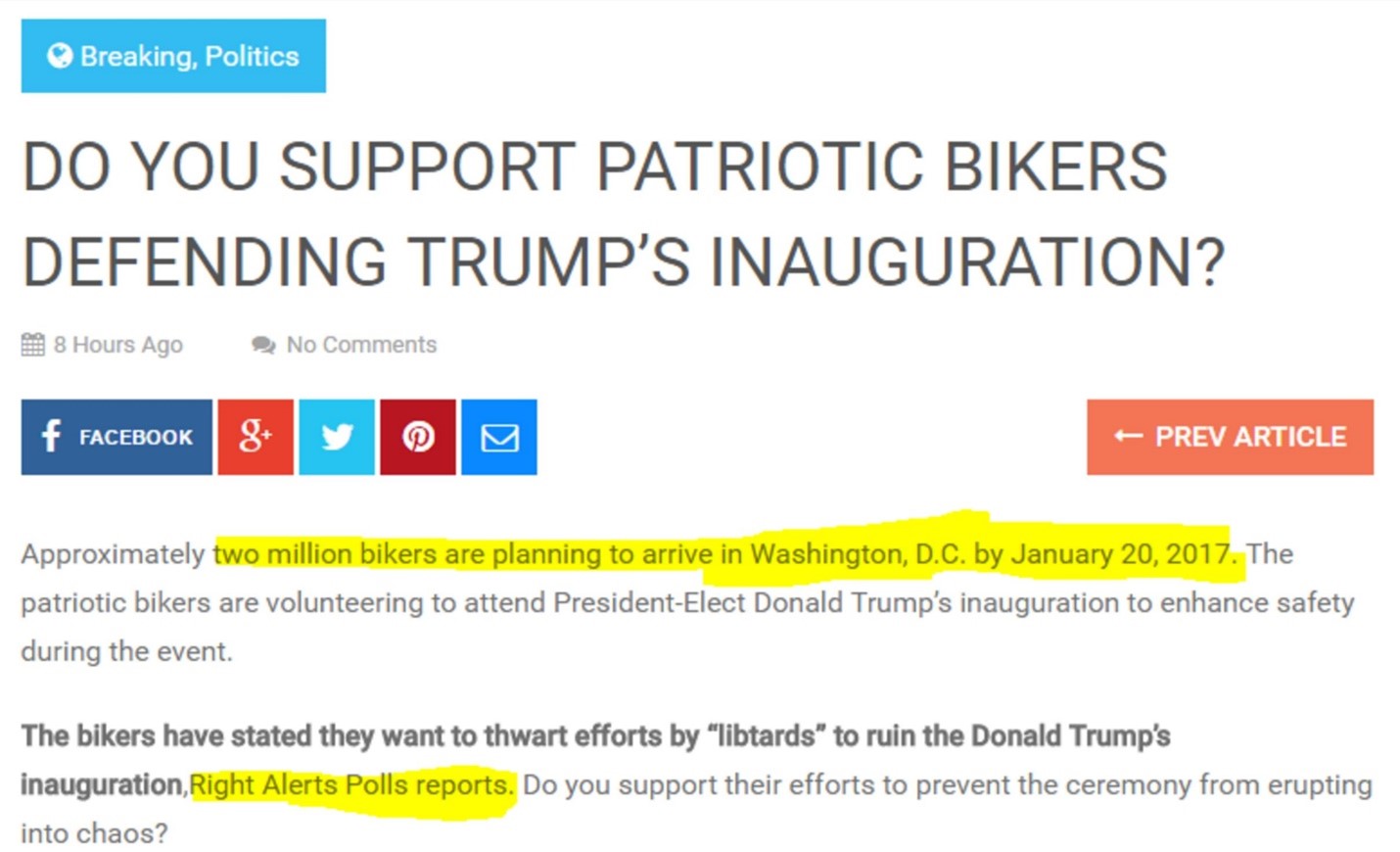

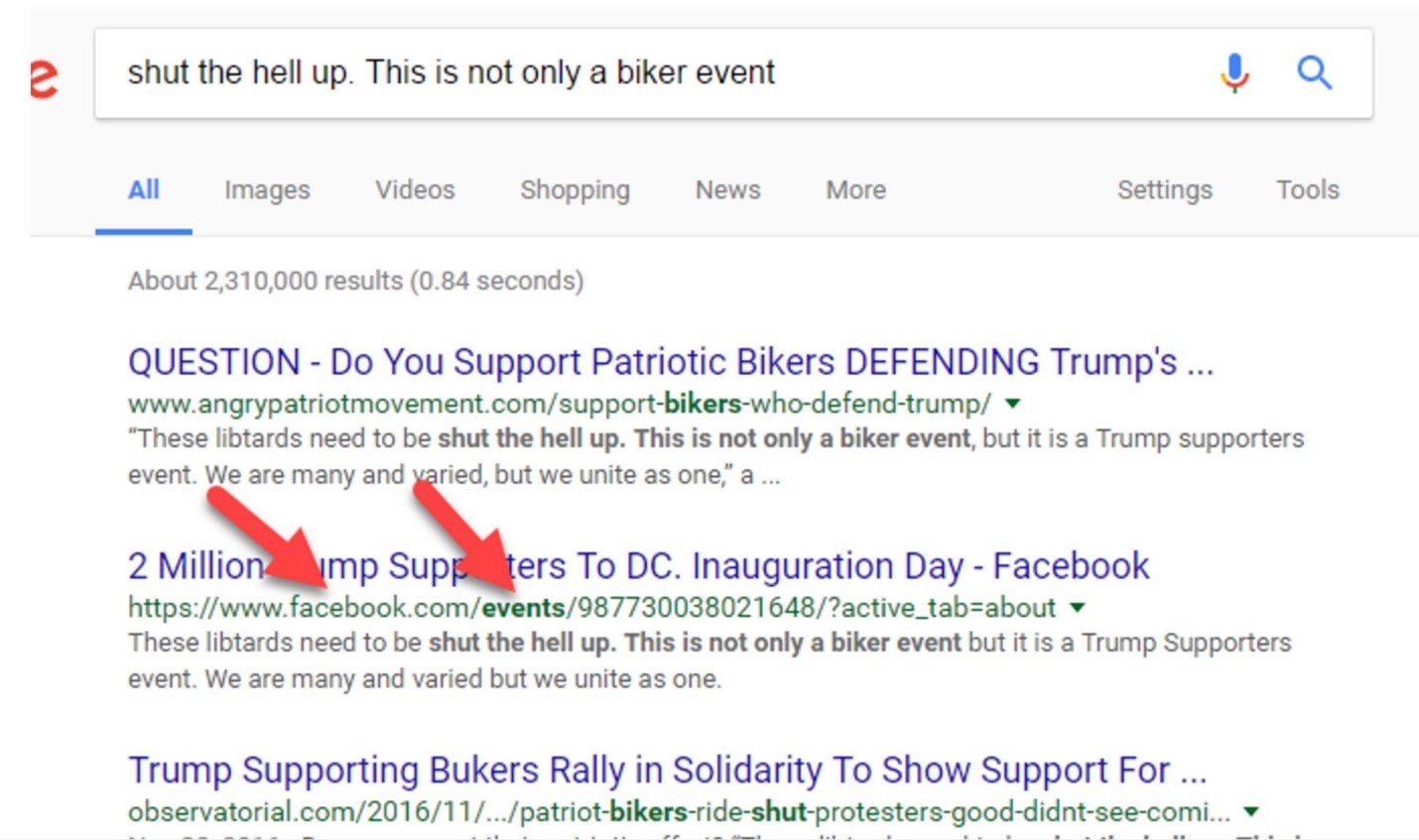

When that information travels around a network, people often fail to link it to sources, or hide them altogether. For example, here is an interesting claim that two million bikers are going to show up for President-elect Trump’s inauguration. Whatever your political persuasion, that would be a pretty amazing thing to see. But the source of the information, Right Alerts Polls, is not linked:

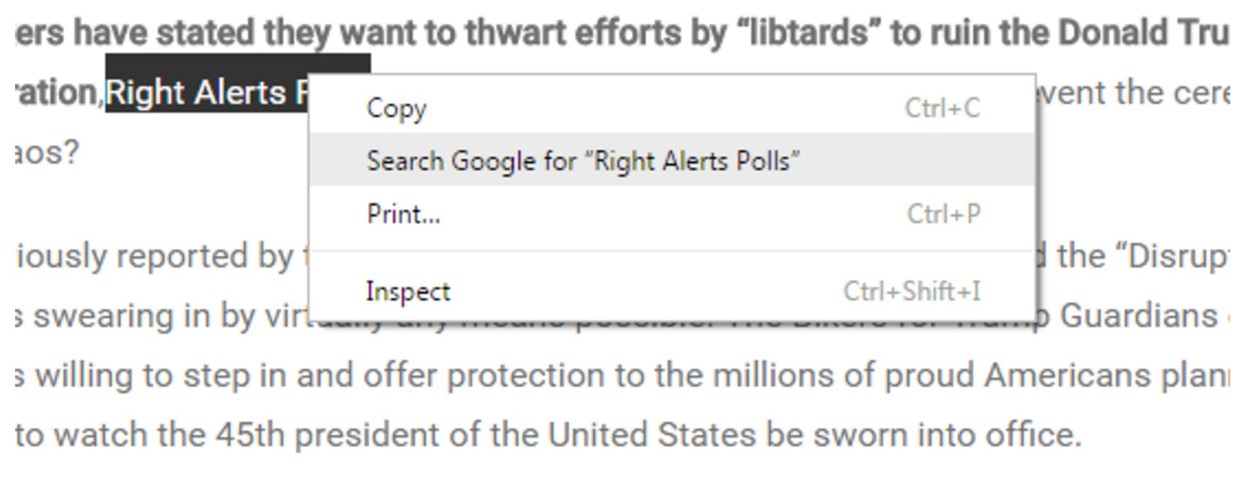

Here’s where we show our first trick. Using the Chrome web browser, select the text “Right Alerts Polls.” Then right-click your mouse (control-click on a Mac), and choose the option to search Google for the highlighted phrase:

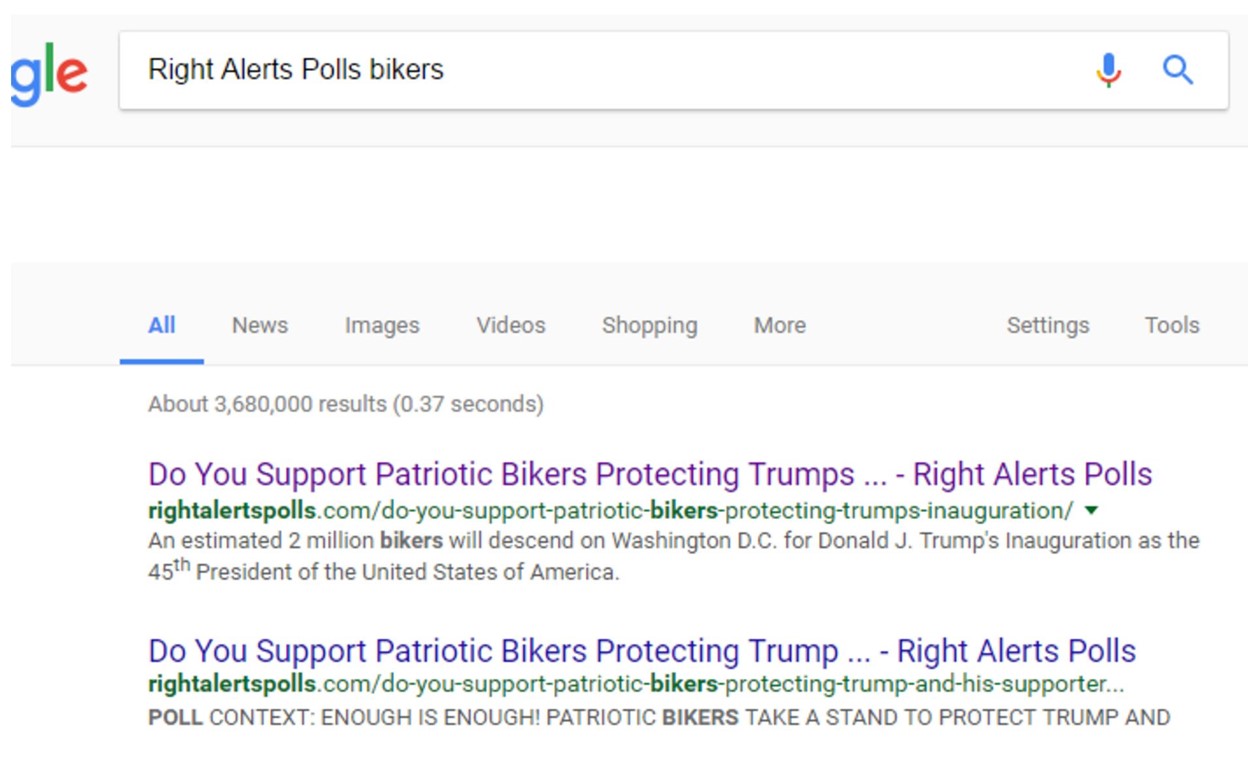

Your computer will execute a search for “Right Alerts Polls.” To find the story, add “bikers” to the end of the search:

We find our upstream article right at the top. Note that if you do not use Chrome, you can always do this the slightly longer way by going to Google and typing in the search terms.

So are we done here? Have we found the source?

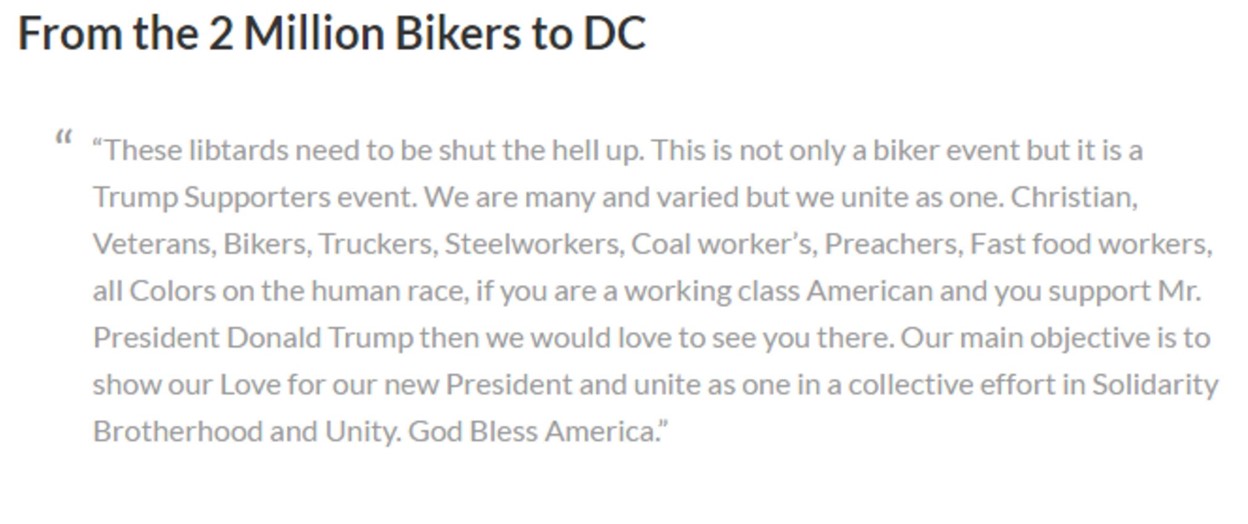

Nope. When we click through to the supposed source article, we find that this article doesn’t tell us where the information is coming from either. However, it does have an extended quote from one of the “Two Million Bikers” organizers:

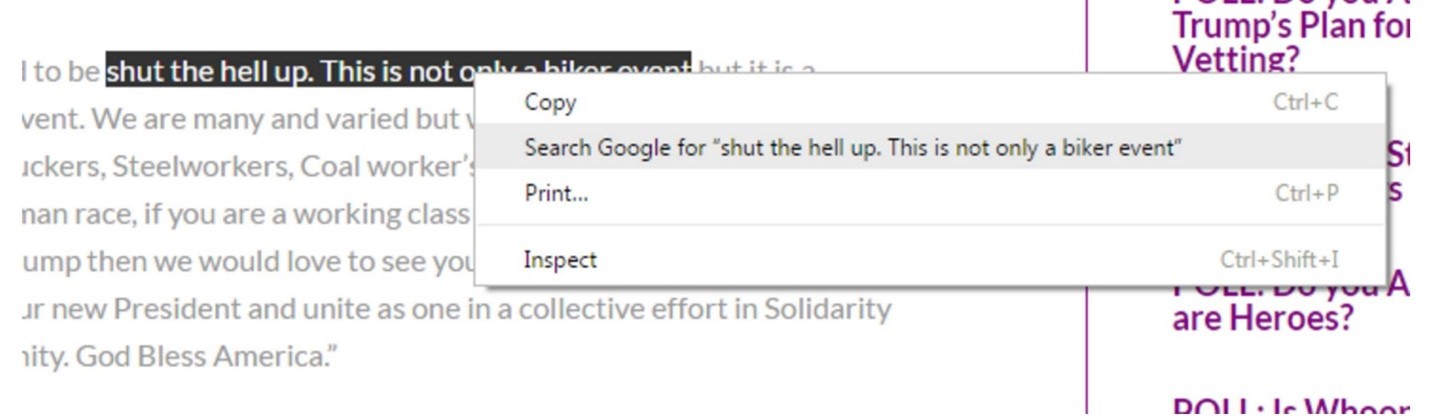

So we just repeat our technique here, and select a bit of text from the quote and right-click/control-click. Our goal is to figure out where this quote came from, and searching on this small but unique piece of it should bring it close to the top of the Google results.

When we search this snippet of the quote, we see that there are dozens of articles covering this story, using the the same quote and sometimes even the same headline. But one of those results is the actual Facebook page for the event, and if we want a sense of how many people are committing, then this is a place to start.

This also introduces us to another helpful practice: when scanning search results, novices scan the titles. Pros scan the URLs beneath the titles, looking for clues as to which sources are best. (Be a pro!)

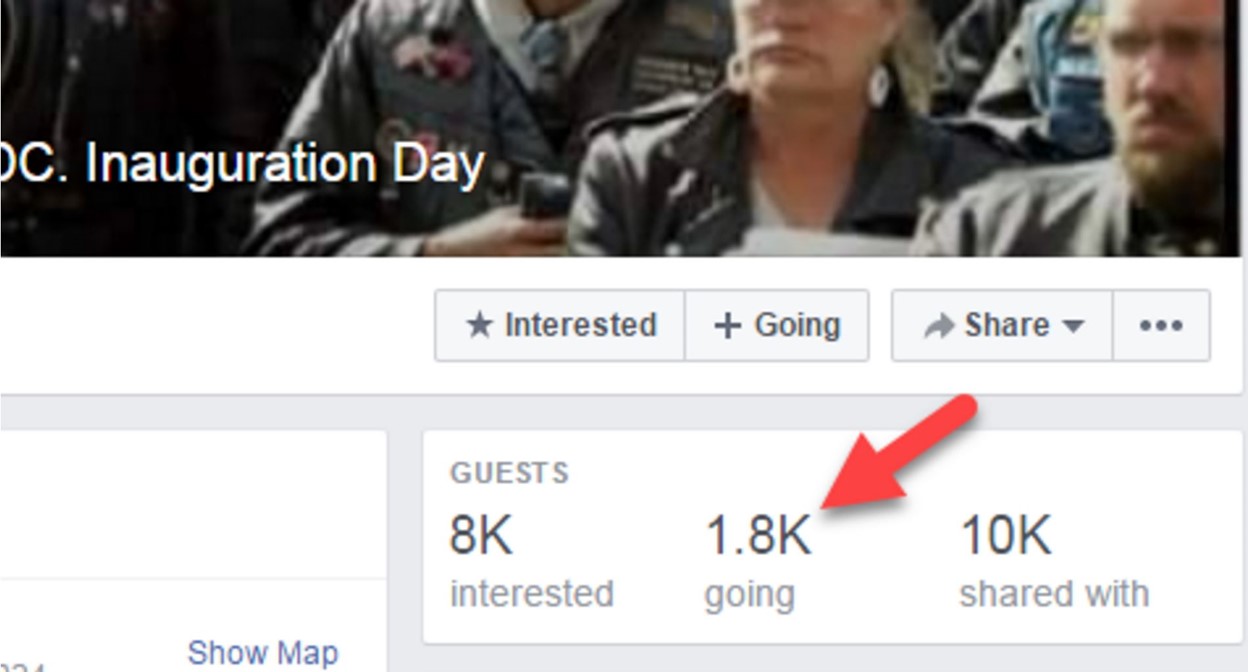

So we go to the “Two Million Biker” Facebook event page, and take a look. How close are they to getting two million bikers to commit to this?

Well…it looks like about 1,800… which is a LOT less than two million! We could have only learned how exaggerated the claims were in the first article by “going upstream” to find the original sources of the information.

Step 3: “Read Laterally” to Evaluate the Source

Even after following a source upstream, you arrive at a page, site, and author that are often all unknown to you. How do you analyze the author’s qualifications or the trustworthiness of the site? Maybe you get lucky and the source is one that is widely known to be reputable, such as the journal Science or the newspaper the New York Times. If your source isn’t known to be reputable, you’re going to need to “read laterally” to find out more about this source you’ve ended up at and asking whether it is trustworthy.

Researchers have found that most people go about this the wrong way. When confronted with a new site, they poke around the site and try to find out what the site says about itself by going to the “about page,” clicking around in onsite author biographies, or scrolling up and down the page. This is a faulty strategy for two reasons. First, if the site is untrustworthy, then what the site says about itself is most likely untrustworthy as well. And, even if the site is generally trustworthy, it is inclined to paint the most favorable picture of its expertise and credibility possible.

When presented with a new site that needs to be evaluated, professional fact-checkers don’t spend much time on the site itself. Instead they get off the page and see what other authoritative sources have said about the site. They open up many tabs in their browser, piecing together different bits of information from across the web to get a better picture of the site they’re investigating. Many of the questions they ask are the same as the vertical readers scrolling up and down the pages of the source they are evaluating. But unlike those readers, they realize that the truth is more likely to be found in the network of links to (and commentaries about) the site than in the site itself.

Watch is video[3] to see how fact-checkers quickly investigate the credibility of journalistic sources and organizations:

Only when they’ve gotten their bearings from the rest of the network do they re-engage with the content. Lateral readers gain a better understanding as to whether to trust the facts and analysis presented to them.

You can tell lateral readers at work: they have multiple tabs open and they perform web searches on the author of the piece and the ownership of the site. They also look at pages linking to the site, not just pages coming from it. Lateral reading helps the reader understand both the perspective from which the site’s analyses come and if the site has an editorial process or expert reputation that would allow one to accept the truth of a site’s facts.

Authority and Reliability: PEA Criteria

Authority and reliability are tricky to evaluate. Whether we admit it or not, most of us would like to ascribe authority to sites and authors who support our conclusions and deny authority to publications that disagree with our worldview. To us, this seems natural: the trustworthy publications are the ones saying things that are correct, and we define “correct” as what we believe to be true. This way of thinking is deeply flawed and can lead to confirmation bias.

So, how do we determine authority and reliability? Wikipedia says reliable sources are defined by process, expertise, and aim (PEA). These criteria are worth considering as you fact-check.

Process

Above all, a reliable source for facts should have a process in place for encouraging accuracy, verifying facts, and correcting mistakes. Note that reputation and process might be apart from issues of bias: the New York Times is thought by many to have a center-left bias, the Wall Street Journal a center-right bias, and USA Today a centrist bias. Yet fact-checkers of all political stripes are happy to be able to track a fact down to one of these publications since they have reputations for a high degree of accuracy, and issue corrections when they get facts wrong.

The same thing applies to peer-reviewed publications. While there is much debate about the inherent flaws of peer review, peer review does get many eyes on data and results. Their process helps to keep many obviously flawed results out of publication. If a peer-reviewed journal has a large following of experts, that provides even more eyes on the article, and more chances to spot flaws. Since one’s reputation for research is on the line in front of one’s peers, it also provides incentives to be precise in claims and careful in analysis in a way that other forms of communication might not.

Expertise

According to Wikipedians, researchers and certain classes of professionals have expertise, and their usefulness is defined by that expertise. For example, we would expect a marine biologist to have a more informed opinion about the impact of global warming on marine life than the average person, particularly if they have done research in that area. Professional knowledge matters too: we’d expect a health inspector to have a reasonably good knowledge of health code violations, even if they are not a scholar of the area. And while we often think researchers are more knowledgeable than professionals, this is not always the case. For a range of issues, professionals in a given area might have better insight than researchers, especially where the question deals with common practice.

Reporters, on the other hand, often have no domain expertise, but may write for papers that accurately summarize and convey the views of experts, professionals, and event participants. As reporters write in a niche area over many years (e.g. opioid drug policy) they may acquire expertise themselves.

Aim

Aim is defined by what the publication, author, or media source is attempting to accomplish. Aims are complex. Respected scientific journals, for example, aim for prestige within the scientific community, but must also have a business model. A site like the New York Times relies on ad revenue but is also dependent on maintaining a reputation for accuracy.

One way to think about aim is to ask what incentives an article or author has to get things right. An opinion column that gets a fact or two wrong won’t cause its author much trouble, whereas an article in a newspaper that gets facts wrong may damage the reputation of the reporter. On the far ends of the spectrum, a single bad or retracted article by a scientist can ruin a career, whereas an advocacy blog site can twist facts daily with no consequences.

Policy think tanks, such as the Cato Institute and the Center for American Progress, are interesting hybrid cases. To maintain their funding, they must continue to promote aims that have a particular bias. At the same time, their prestige (at least for the better known ones) depends on them promoting these aims while maintaining some level of honesty.

In general, you want to choose a publication that has strong incentives to get things right, as shown by both authorial intent and business model, reputational incentives, and history.

Practice Reading Laterally to Evaluate a Source

Evaluate the reputations of the following sites by “reading laterally.”

Google search the sites to determine the reputability of each site: Who runs them? To what purpose? What is their history of accuracy, and how do they rate on process, aim, and expertise?

- http://cis.org/vaughan/...

- https://codoh.com/media/files/...

- http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/...

- http://www.dailykos.com/...

- https://nsidc.org/

- http://www.smh.com.au/environment/weather/...

- http://occupydemocrats.com/2017/02/11...

- http://principia-scientific.org/...

- http://www.europhysicsnews.org/articles/epn/abs/2016/05/...

- https://www.rt.com/news/...

- http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/world/us/...

- http://www.naturalnews.com/...

- http://fauxcountrynews.com/...

Remember, you can’t trust what the site says about itself, so try using a search query with a minus sign to eliminates results from the site. For example, if you are evaluating the Occupy Democrats site, you might enter this as a search term: “occupydemocrats.com -site:occupydemocrats.com” so that your search results only include information ABOUT the site and not FROM the site.

Evaluating Journal Articles

Many people assume that journals are reputable. While you can generally trust journals that your college library subscribes to, you cannot blindly trust journals that are published online – some are “paper mills” that don’t peer review and simply publish anything submitted to them.

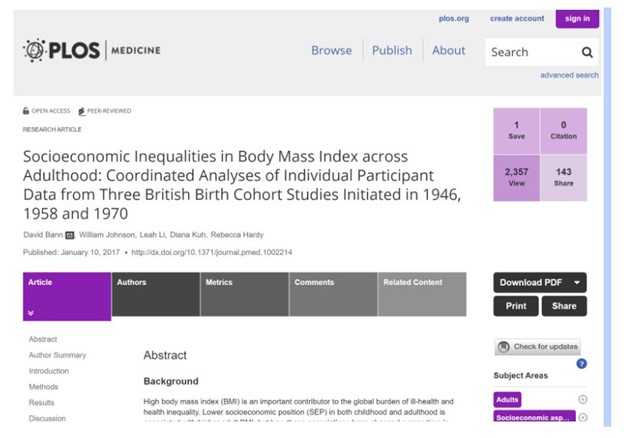

Consider this journal:

Is it a journal that gives any authority to this article? Or is it just another web-based paper mill?

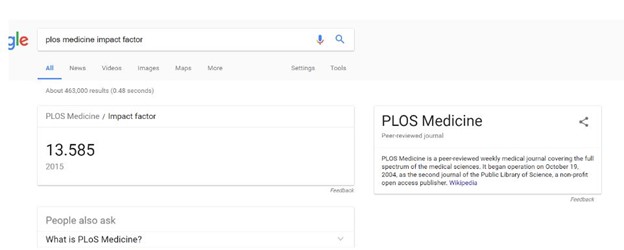

Our first check is to see what the “impact factor” of the journal is. This is a measure of the journal’s influence in the academic community. While a flawed metric for assessing the relative importance of journals, it is a useful tool for quickly identifying journals that are not part of a known circle of academic discourse, or that are not peer-reviewed.

We search Google for PLOS Medicine, and it pulls up a knowledge panel for us with an impact factor.

Impact factor can go into the 30s, but we’re using this as a quick elimination test, not a ranking, so any above 1 is a positive starting point.

Now we can look at the author himself: is the author an authority?

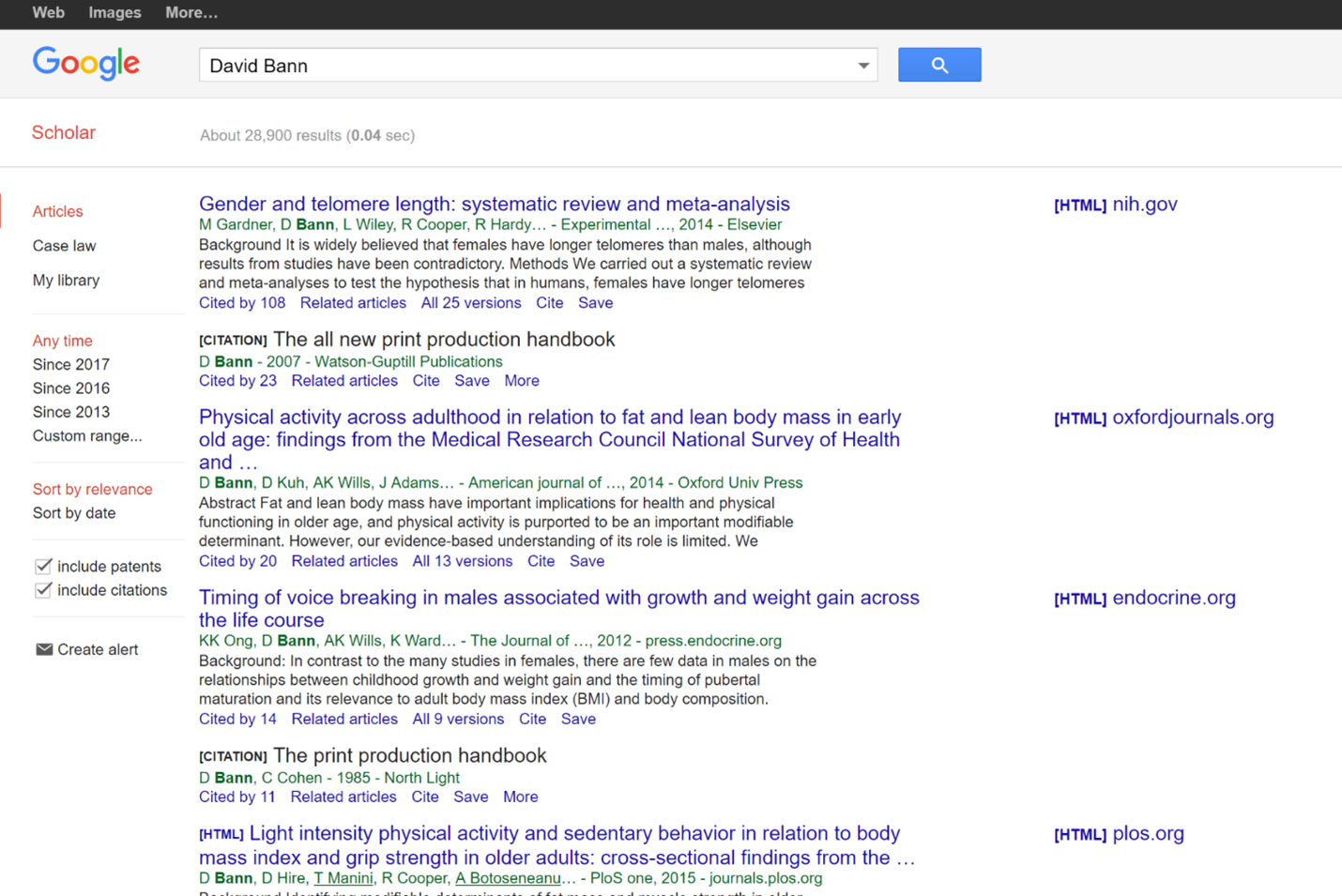

Let’s do a Google Scholar search for David Bann, the author of the above PLOS article:

We see a couple things here. First, he has a history of publishing in this area of lifespan obesity patterns. At the bottom of each result we see how many times each article he is associated with is cited. These aren’t amazing numbers, but for a niche area they are a healthy citation rate. Many articles published aren’t cited at all, and here at least one work of his has over 100 citations.

Additionally if we scan down that right side column we see some names we might recognize–the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and another PLOS article.

Keep in mind that we are looking for expertise in the area of the claim. These are great credentials for talking about obesity. They are not great credentials for talking about opiate addiction. But right now we care about obesity, so that’s OK.

By point of comparison, we can look at a publication in Europhysics News that attacks the standard view of the 9/11 World Trade Center collapse. We see this represented in this story on popular alternative news and conspiracy site AnonHQ:

The journal cited is Europhysics News, and when we look it up in Google we find no impact factor at all. In fact, a short investigation of the journal reveals it is not a peer-reviewed journal, but a magazine associated with the European Physics Society. The author here is either lying, or does not understand the difference between a scientific journal and a scientific organization’s magazine.

So much for the source. But what about the authors? Do they have a variety of papers on the mathematical modeling of building demolitions?

If you enter the names into Google Scholar, you’ll find that at least one of the authors does have some modelling experience on architectural stresses, although most of his published work was from years ago.

What do we make of this? It’s fair to say that the article here was not peer-reviewed and shouldn’t be treated as a substantial contribution to the body of research on the 9/11 collapse. The headline of the blog article that brought us here is wrong, as is their claim that a European Scientific Journal concluded 9/11 was a controlled demolition. That’s flat out false.

Using Google to Find Credible Information

We’ve seen that you can’t trust everything you read online, but that doesn’t mean that there isn’t great information available on Google – you just have to be a savvy searcher.

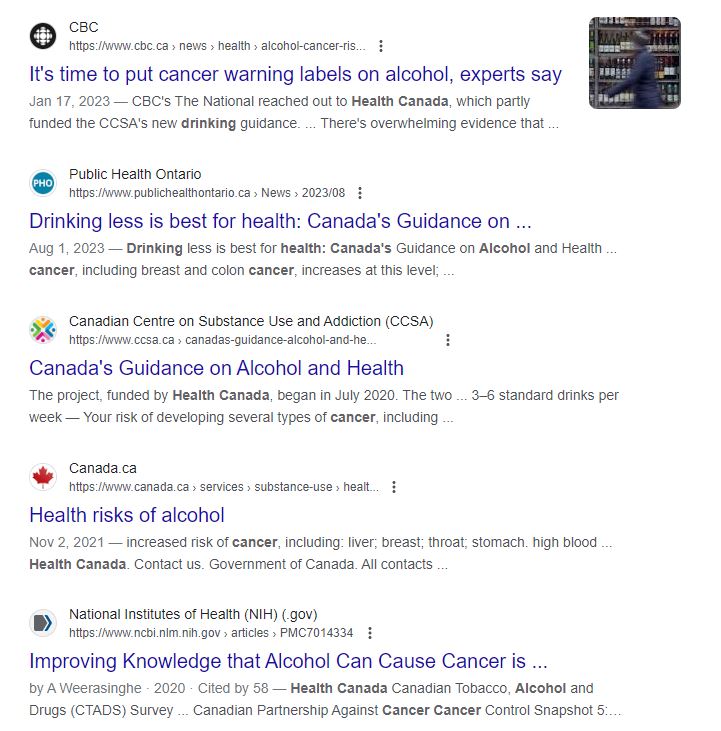

Let’s say that you are interesting in the health effects of alcohol consumption, and you’ve heard that the consuming alcohol can cause cancer. You want to find credible information about this claim. Let’s see if we can get a decent summary from a respected organization that deals with these issues.

This takes a bit of domain knowledge, but for information on disease, Health Canada and the United States’ National Institutes of Health (NIH) is considered one of the leading authorities. What do they say about this issue?

What we don’t want here is a random article. We’re not an expert and we don’t want to have to guess at the weights to give individual research. We want a summary.

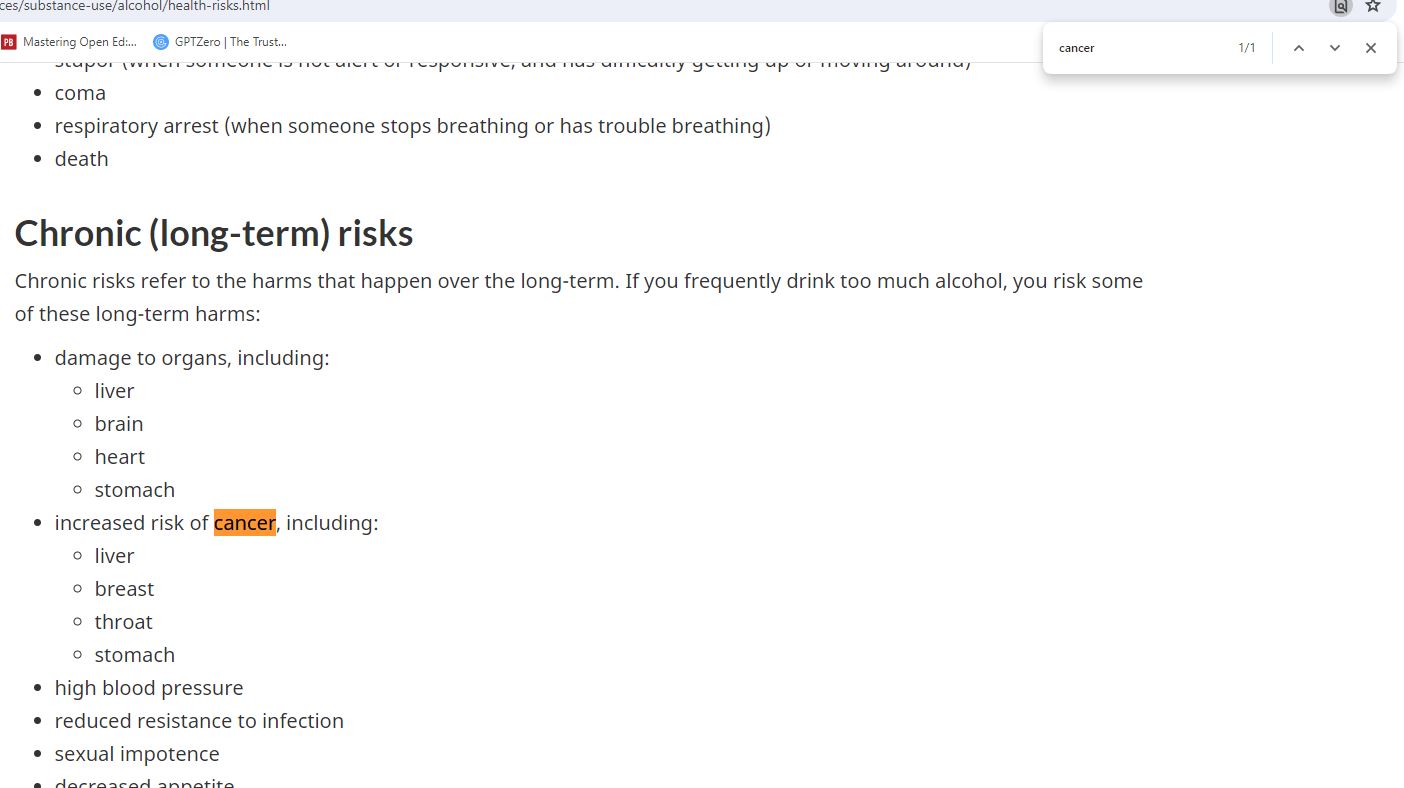

And as we scan the results we see a link to an article on Canada.ca, which is the Government of Canada’s official domain. We click on the link and see that the article lists many dangers of alcohol. We want quick information, so we use Ctrl+F to open a search bar so we can search specifically for “cancer”:

It’s important to remember that we DIDN’T just click on the first result, which was a CBC News article. Too often, we execute web search after web search without first asking who would constitute an expert. Unsurprisingly, when we do things in this order, we end up valuing the expertise of people who agree with us and devaluing the expertise of those who don’t. If you find yourself going down a rabbit hole of conflicting information in your searches, back up a second and ask yourself: whose expertise would you respect? Maybe it’s not the Government of Canada. Maybe it’s the NIH or the Mayo Clinic or the World Health Organization. Deciding who has expertise before you search will mediate some of your worst tendencies toward confirmation bias.

Avoid Confirmation Bias

It is important to phrase your search term to avoid “confirmation bias”.

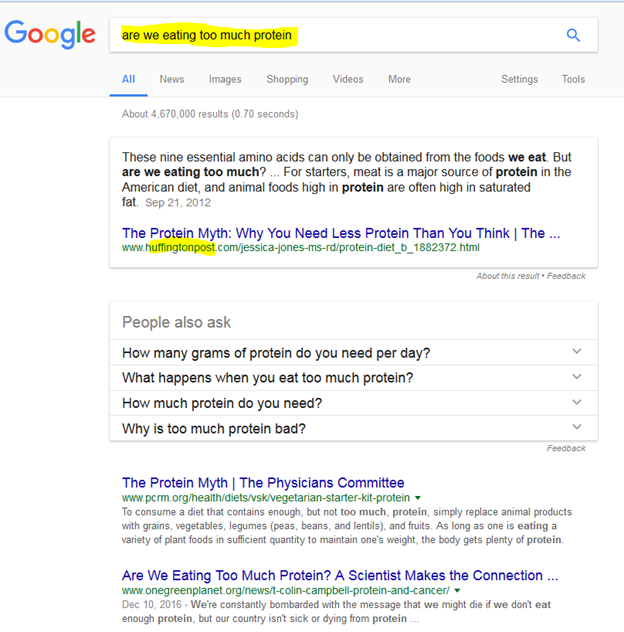

If we enter “Are we eating too much protein” into the search bar, Google returns results that confirm this assumption:

Looking more closely, we can see that the first results are from the Huffington Post (now HuffPost) and a website from a vegan advocacy group – neither are likely to be highly credible sources.

Tips to Avoid Confirmation Bias in Searches

- Avoid asking questions that imply a certain answer. If I ask “Did the Holocaust happen?,” for example, I am implying that it is likely that the Holocaust was faked. If you want information on the Holocaust, sometimes it’s better just to start with a simple noun search, e.g. “Holocaust,” and read summaries that show how we know what happened.

- Avoid using terms that imply a certain answer. As an example, if you query “Women 72 cents on the dollar” you’ll likely get articles that tell you women make 72 cents on the dollar. But is you search for “Women 80 cents on the dollar” you’ll get articles that say women make 80 cents on the dollar. Searching for general articles on the “wage gap” might be a better choice.

- Avoid culturally loaded terms. As an example, the term “black-on-white crime” is term used by white supremacist groups, but is not a term generally used by sociologists. As such, if you put that term into the Google search bar, you are going to get some sites that will carry the perspective of white supremacist sites, and be lousy sources of serious sociological analysis.

- Plan to reformulate. Think carefully about what constitutes an authoritative source before you search. Once you search you’ll find you have an irrepressible urge to click into the top results. If you can, think of what sorts of sources and information you would like to see in the results before you search. If you don’t see those in the results, fight the impulse to click on forward, and reformulate your search.

- Scan results for better terms. Maybe your first question about whether the holocaust happened turned up a lousy result set in general but did pop up a Wikipedia article on Holocaust denialism. Use that term to make a better search for what you actually want to know.

Want to learn more about how to fact- and source-check? Take this free online course: Check, Please!

- Caulfield, M. A. (2017, January 8). Web literacy for student fact-checkers. BC Open Collection by BCcampus. https://collection.bccampus.ca/textbooks/web-literacy-for-student-fact-checkers-361/ ↵

- Caulfield, M. (2018, June 29). Online verification skills - Video 1: Introductory video. YouTube. https://youtu.be/yBU2sDlUbp8 ↵

- Caulfield, M. (2018, June 29). Online verification skills - Video 2: Investigate the source. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hB6qjIxKltA. ↵