10 Active, Critical Reading

Learning Objectives

After completing this chapter, you will be able to

- define active and critical reading

- employ strategies to be a more effective reader

- take notes using the Cornell method

Your brain uses a variety of techniques when you are reading. These are helpful in letting you read quickly. However, sometimes your brain may “fill in the blanks” to add information that isn’t there. Therefore, reading to understand and recall specific details can require more attention, especially if the information is new. In college you may find an increased amount of reading, especially in your introductory courses when you are learning new terminology, definitions, and theories in your field of study. For this reason, you should use active reading strategies to help you understand what you’ve read and then recall it later.

Purposes for Reading

The purpose of reading can be personal or academic.

Reading for personal reasons might involve reading novels or magazines for enjoyment or leisure, reading instructions or directions to complete a personal project, reading social media posts to stay connected with friends, reading rental agreements or financial documents to understand legal contractual obligations, or reading websites or newspapers to obtain up-to-date information on current events.

Academic reading might involve reading a textbook to gain new knowledge about a topic, reading a manual or handbook so you can follow instructions to complete a procedure or process, or reading an article or example essay so you can analyze paragraph structure, evaluate the reader’s use of evidence, and respond to new ideas and opinions in a critical and reflective way.

When we read for different purposes, we need to use different reading strategies.

Active Reading

It is important to read actively when you need to understand information and recall it later. When you read actively, you are engaging with the text in a deeper and more complex way than when you are reading just for pleasure. Active readers are concerned about understanding and remembering what they’ve read, so they make sure to focus on the text by making notes and highlighting important terms and ideas.

Watch the following Learning Portal video on strategies you can use to become a more active reader[1].

Critical Reading

Active reading will help you understand and retain what you’ve read. However, in college you are often asked to evaluate, analyze, and assess a reading by comparing what you’ve read to your previous knowledge and to other texts on the subject.

Some students may wonder why they have to use critical reading skills. Why can’t the instructor just provide the true answers or methods in one PowerPoint or textbook? Sometimes it is possible – and necessary – to provide detailed, accurate information in one handbook: for example, pharmacology manuals, accounting standards, and engineering manuals.

However, in many cases, you will be required to assess the accuracy, point-of-view, bias, currency, and reliability of texts and information you encounter online and in traditional texts. Also, you need to be exposed to other points of view on a topic, including those you don’t agree with.

Employers in many fields of work expect college graduates to quickly analyze and assess information in the workplace and judge its usefulness. Often new information will need to be applied immediately at work.

For all of these reasons, critical reading is an essential skill.

Critical reading requires you to read not only for facts and opinion, but to also assess, analyze, and make judgements about the texts.

Reading critically includes asking the following questions:

- How does the structure, word choice, and writing style affect your opinion of the writing?

- How do facts and opinions in this text compare or contrast with other information you’ve read or heard?

- Is the evidence provided primarily objective or subjective? Is it reliable and persuasive?

- Is the writer’s argument sound and valid or does it contain assumptions or logical fallacies?

- Is the reading a current, relevant, accurate, and authoritative source of information? What is the writer’s purpose or point of view on the topic? See the Researching chapter of this e-text for more information on how to evaluate the reliability of a reading.

Strategies for Effective Reading

College reading assignments may require much more in-depth attention and may be more time-consuming than reading you have done in your leisure time or for personal reasons. Use these strategies to help you become a more active and effective reader.

1. Preparing to Read

If you are reading a chapter in a textbook, first familiarize yourself with the textbook as a whole. Glance through the table of contents, sections of the book, introductions, glossary of terms and practice quizzes. Then explore the assigned chapter. Determine how much time you need to set aside to read it by considering how long and complex the chapter is. Look at any headings, illustrations, tables, and review questions. Read the introduction and summary. Get an understanding of the “gist” or main points of the reading before you start reading closely for specific details.

Before you begin reading, remember your purpose. Has your professor provided specific questions for you to answer? Will you be quizzed on this material? Do you need to form a point of view on the material so that you can participate in a class discussion? Make a list of questions that you hope to answer in your readings; this will improve your focus as you read. Reading Plan to read the required section twice.

2. Reading for Gist

The first time you read, read the entire chapter or article all the way through. Focus on gaining an understanding of the main point, or gist, of the reading. What is it about? What is the most important information? If a point of view is expressed, how is that opinion supported?

To make the reading more meaningful, try to visualize the reading as images in your mind, or reflect on your personal experiences and prior knowledge of the subject.

3. Reading for Details

Once you have a good understanding of the article in general, now you can read for specific information.

Take the first question you have prepared or from the assignment; begin to read the chapter and stop when you have found the answer. Highlight it or write it down in short form and leave space for further notes. Keep reading the chapter, answering the questions as you go.

Sometimes your teacher will ask you to find the main idea of a text or paragraph. This can be challenging and confusing. Here are some steps to follow:

- Read the entire text or paragraph to understand the gist. Look at the title, headings, and/or illustrations for a clue to the main idea.

- Read the last paragraph or sentences; usually the summary of the main idea will be there.

- Sometimes you will need to re-read the text to identify the main idea.

- Answer these questions about the reading: What is the focus or main topic of this text? What is the writer’s point of view? Are alternate points of view given? What evidence is provided to support the author’s point of view?

- Answer these questions about the topic: Who? What? Where? When? And How?

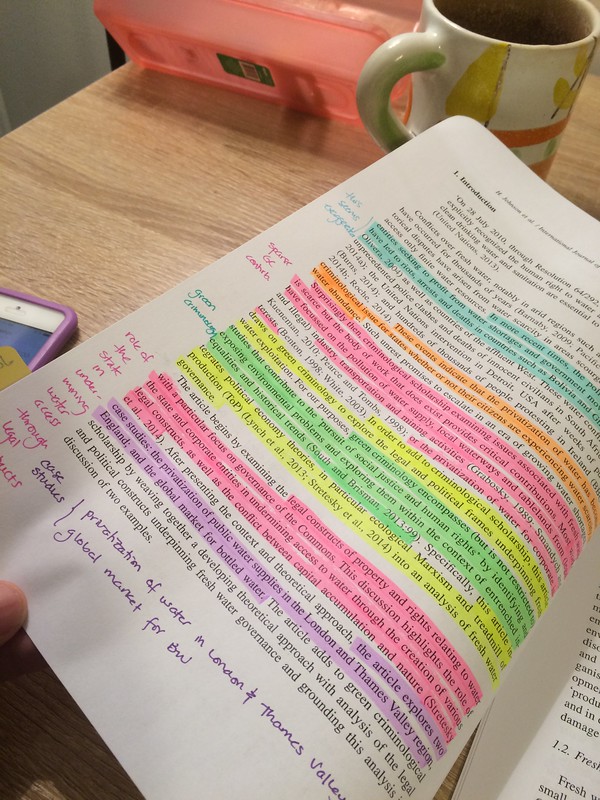

Whatever your purpose, during the second reading maintain focus on the reading by keeping an internal summary and reread sentences or sections as necessary, and use annotation techniques (circling, highlighting, and making notes in the margins) to draw attention to important details, key ideas, and important vocabulary words.

Highlight main ideas and important details, but avoid highlighting entire sentences or minor points or examples. Highlight only the most important information. In the margins, add questions and comments about information that intrigues or confuses you. You can also add images and diagrams to enhance your understanding. Use margin notes to personalize the text. Circle and then look up any unknown words that you think are important to the subject – remember, you don’t need to know every word in a reading to understand it, but you do need to know relevant technical terms. Keep a list of new vocabulary in a special notebook or Word document.

4. Reviewing

After you’ve completed a thorough reading, you may want to take notes on what you’ve read. Taking notes is an excellent way to solidify your learning and to ensure that you can find key information quickly when you need it.

Watch the following Learning Portal video to learn about the importance of taking notes to improve your learning[2]:

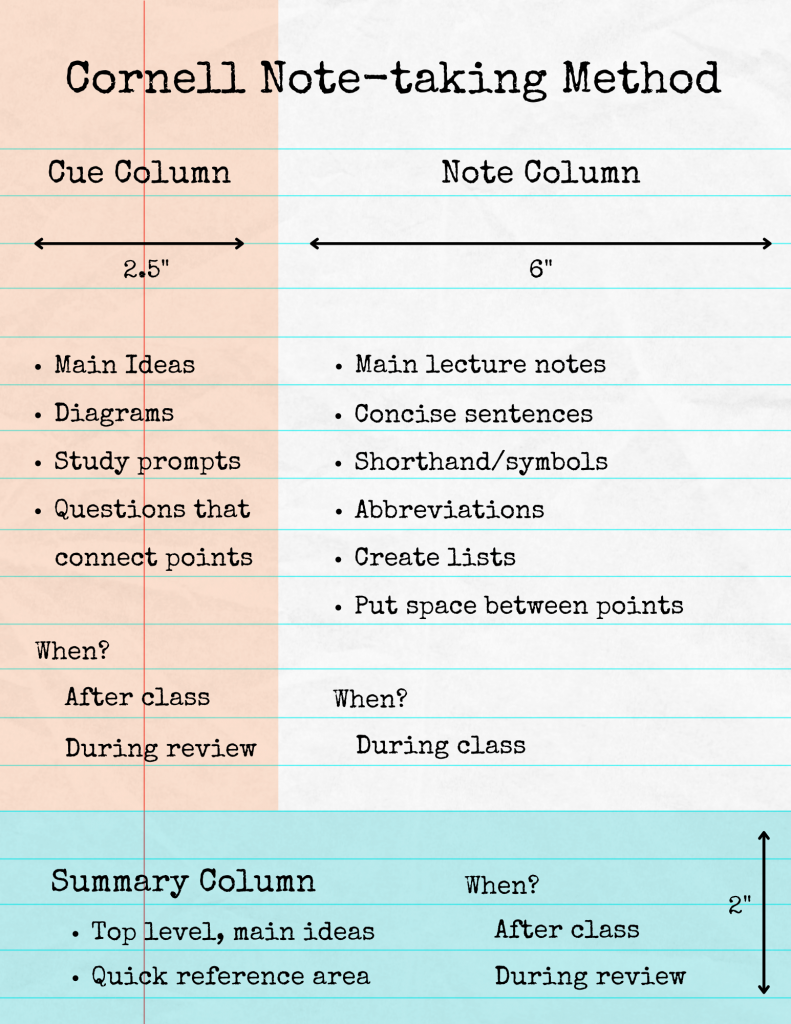

Many people recommend using the “Cornell Note-Taking” method to take notes. This method can be used to take notes from readings and also to take notes from class lectures. The image below gives an example of how a page can be broken down during the note-taking process[3]:

Watch the following Learning Portal video to learn how to use the Cornell note-taking method[4]:

Once you’ve completed your notes, you can use them to help you study. If you were reading to answer specific questions, cover up the answer and key ideas you have written on the right-hand side of your Cornell notes. Can you still answer the question? Check your mental review against what you have written.

In class, add any additional information from your instructor to your notes.

Try this activity by otacke to practice your Cornell note-taking ability. You can type but can’t save your responses in this Pressbook.

Additional Reading Tips

Information in this section has been adapted from Chapter 12: Reading in A Guide for Successful Students by Irene Stewart and Aaron Maisonville (St. Clair College)[5], which is made available by Pressbooks under a CC BY-NC-SA license except where otherwise noted.

Pace yourself: Figure out how much time you have to complete the reading assignment.

Divide your work: Divide the assignment into smaller blocks rather than trying to read the entire assignment in one sitting.

Schedule your reading: Set aside blocks of time, preferably at the time of day when you are most alert, to do your reading assignments.

Prioritize your work: Read the most difficult assignments early in your reading time when you are freshest.

Choose your environment: Choose to read in a quiet, well-lit space. Read in an upright position at a desk or on a couch. Your position should be comfortable and your body supported.

Avoid distractions: Active reading takes place in your short-term memory. Every time you move form task to task, you have to “reboot” your short-term memory and you lose the continuity of active reading.

Avoid reading fatigue: Work for about fifty minutes and then give yourself a break for 5-10 minutes. Put the book down, walk around, get a snack, stretch, or do some deep kneed bends. Short physical activity will do wonders to help you feel refreshed.

Make it interesting: Try connecting the material you are reading with your class lectures or with other chapters. Ask yourself where you disagree with the author. Approach finding answers to your questions like an investigative reporter. Carry on a mental conversation with the author.

- The Learning Portal/Le Portail d’Apprentissage. (2016, August 31). How to use active reading techniques [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hVZLUQSPuhc. ↵

- The Learning Portal/Le Portail d’Apprentissage. (2021, February 4). Why you should take notes to improve learning [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DxFbMqxXCVE. ↵

- Veillieux, H. (2022, April 12). Cornell-NT-Method_infographic [Digital Image]. In Active, Critical Reading. Confederation College. https://bit.ly/3jBswHy. CC BY 4.0. ↵

- The Learning Portal/Le Portail d’Apprentissage. (2016, September 1). How to use the Cornell note-taking method [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FrKfZ5VYWCQ. ↵

- Stewart, I., & Maisonville, A. (2018, February). A guide for successful students. St. Clair College. https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/studyprocaff/ ↵