Reimagining Archival Spaces

More-than-human spatial archives?

Many of the archives discussed thus far in the course have been collections of documents or data. These are what some scholars would call the human archives. Yet the existence of a human archive implies the existence of a more-than- or other-than-human archive. These are generally referred to as “natural” archives (a term that requires further critical thought beyond this module), and tend to consist of natural specimens that have been collected and compiled in a way that maintains their context, often with a particular goal in mind. Natural archives are especially common in paleoclimatology, where proxies such as tree rings can be used to study past climatic conditions. However, other fields also use natural archives, even if they might not describe them in those terms; herbaria, for example, could be described as natural archives. As with documents stored in human archives, these specimens have to come from somewhere; often this locational context is extremely important to the goal of the archive, and thus natural archives can be particularly spatial. For example, it can be important to understand where a plant was collected to understand species distributions, or from a more humanistic context, what kind of practices might have been used in collecting it.

While at first glance natural and human archives are completely different, they do have some deep similarities. As Zachary Nowak put it in his discussion of natural archives, “both are material traces of the past” (2022). Also, it is important to realize that, like all archives, natural archives are not perfect representations of the real world; specimens must be assessed, organized, and then accessed and interpreted in ways that mirror the contents of human archives, and are thus subject to the same cultural forces. However, is it possible to have archives where this is not the case? Humanities scholars have begun to conceptualize the land and landscape itself as an archive, in that it contains traces of the past which you must have a certain amount of historical knowledge to interpret (Norquay, 2016). Certainly, if the archive is something that can exist outside of human intervention, then some of the exclusions introduced into archival space by the practices of assessing and cataloguing disappear! The question remains, however, if something like a landscape, a forest, or even a city (see Roberts, 2015) can be an archive before it has the context these practices assign to it. Despite describing the land as an archival document, for example, Norquay later describes the archive as a thing she is “creating” and “conjuring.” In the next section, we examine some examples that emerge from this broadened understanding of archive, using the examples of climate proxies.

Proxy data: Reconstructing past climates

Digital humanities scholars sometimes draw on proxy datato tell stories about the past. Proxies are variables that might not seem directly relevant for the topic at hand, or that might have been collected in a different context, but that can be used in combination with other methods to understand something that cannot be easily studied. Interdisciplinary scholars interested in past environments use proxies by putting them into conversation with the methods, data, and technologies of the present, to reconstruct aspects of the past.

Historians, geographers, and paleoclimatologists, among others, use climateproxies to imagine, reconstruct, and learn from past climates. Unsurprisingly, digital and physical archives become vital sources of historical records that can be used for such tasks. This type of imaginative, interdisciplinary research has been aided immensely by the digitization of historical analogue records that provide both qualitative and quantitative information on environments. These materials can include a range of analogue and digital primary sources such as: meteorological records, ship logs, field journals, e-mails, photographs, paintings, films, and audio recordings (e.g. soundscape recordings, bird recordings, oral history recordings).

As we indicated in the previous module, an expanded understanding of what constitutes an archive or “site” of historical knowledge production more generally (such as GLAMs) provides new inspiration for re-storying the past. Who – or what – can preserve history? Who – or what – can be a storyteller? How are stories preserved, and for what purpose?Broadening the “archival imagination” (Craig, 1992) to include more-than-human environments raises new and exciting questions about historical context, provenance, and preservation. The following examples of more-than-human “storytellers” push the boundaries of concepts like archives, data, fields, knowledge, and memory.

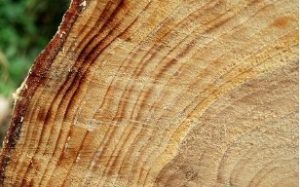

Trees, which produce annual growth rings, are perhaps the most widely known climate proxies. It has long been known that tree rings tell their own stories of climate conditions, including temperature and precipitation changes, allowing researchers to reconstruct past climates and major events like floods and droughts. For example, A. E. Douglass, who is often credited with founding dendrochronology as a discipline, referred to tree rings as “talkative” diaries in a 1929 National Geographic paper (see also Csank, 2020). However, ideas about the “voices” of trees (and other living beings) have circulated far longer than Western disciplines, particularly through Indigenous knowledges and worldviews that honour a more interconnected relationship between land and other living beings, and that resist anthropocentric approaches to climate change.

Soil profiles, such as those appearing within soil monoliths (vertical slices of soils), preserve trace metals and contain carbon and oxygen isotopes that can be important clues about the past, including what happened on the land and when. For an example of historical research using soil monoliths, see Pete Anderson’s reflection on “Reading Deep Horizons” for the Network in Canadian History and Environment (NiCHE) blog. Anderson’s work also connects with experimental farms as records of historical and environmental change, and as sites where biogeographical records, including soil samples, are held.

Similar to soils, pollen provides another rich source of historical information on past environments. Although perhaps novel to scholars across the geohumanities and digital humanities, the idea is not necessarily new; John Iverson’s 1941 paper connecting pollen to histories of tree clearing by Neolithic peoples set into motion the field of palynology (the study of pollen) and has since influenced interdisciplinary climate and biogeographical storytelling. More recent examples of the use of palynological records for reading and telling the past can be found in a special issue on “interdisciplinary research for past environments” for Historical Geography (see Schoolman et al., 2018; and special issue introduction by Greer et al., 2018).

The list of climate proxies is long, and includes other examples like corals and sponges, ice cores, guano, and proxies from underwater environments such as shipwrecks and underwater munitions (see Souchen, 2021), that preserve historical information in unique ways. For an ongoing example of a community-based project that draws on pollen studies, tree studies, and other historical proxies to “bring archives to life” through ecological restoration, see the Carrifran Wildwood project. For a more extensive list of climate proxies in general, see Carbon Brief‘s post, “How ‘proxy’ data reveals the climate of the Earth’s distant past” (2021).

It is essential to remember that, while the proxy data and more-than-human collections typically used in climate research rely heavily on Western, Global North, and Eurocentric scientific data, ideas about the land as language, history, and storyteller have been embedded in Indigenous worldviews since time immemorial. As settler scholars, we (the authors of this module) encourage students to consult with literature written specifically by Indigenous scholars on these topics. For more on climate storytelling (and story listening) through Indigenous and traditional ecological knowledges (IK and TEK), see Wendy Makoons Geniusz (2009), Linda Tuhiwai Smith (2013), Deborah McGregor (2004), and Vine Deloria (1997).