Lab 1 – Reimagining the Archives: Online Collections

Introduction

What is an archive?

A quick scroll through the first page of Google will reveal a wide range of definitions for “archive.” An archivist might prefer to define an archive as a group of materials all generated by a person or organization, which are preserved together based on archival principles (Theimer, 2012). Scholars across the digital humanities may prefer to describe an archive more broadly, perhaps as a “collection of meaningful objects” (Price, 2009) or of digital representations of those objects. The latter definition opens up the possibility that something like a forest could be an archive (Csank, 2021). Further, while traditional archives tend to prioritize collections of textual documents, they can equally include photographs, e-mails, databases, and audio or video recordings. Neither definition necessarily limits the kind of materials that an archive can contain.

As this is a digital humanities course, we will be working from the broader definition of archive, but you should be aware that there are many meanings for this word, and that other people may not be using it the same way as you. This blog post provides an excellent summary of the different meanings, if you would like an explanation of further possibilities [https://blogs.loc.gov/thesignal/2014/02/what-do-you-mean-by-archive-genres-of-usage-for-digital-preservers/].

Archives and power

One of the themes that you will notice throughout these labs is the necessity to think deeply about your sources of information and data; this is sometimes called critical reading. Students at the start of their learning journey have a tendency to assume that certain sources of information are more likely to be neutral and unbiased; this is particularly true for sources of information that are usually seen as authoritative, such as books and maps. This same trust often applies to archives as well. However, it is important to recognize two points here. First, archives are compiled by people, who must make decisions about what to include and how to catalogue it. This is even true of archives compiled by web scraping tools, which after all must be built by people and given parameters to work within. Thus, the beliefs and understandings of the people compiling the archive will influence the archive.

Second, archives are bound up with power in various ways. One way in which archives interact with power is that they are often created by people or groups with power. Physical archives, at least, need space, and preferably conditions conducive to the preservation of the material they store. They also require staff with specialized knowledge and training in the work of archives. All of these things require investments of money and time that can be most easily made by powerful entities, such as large businesses, governments, or universities. This is not to say that people or organizations not traditionally seen as powerful can’t create archives, but it is certainly less common. Another related way that archives interact with power is that they encode dominant structures, which are often structures of power. Archives tend to be organized based on categorization and classification of the materials they contain. It’s important to realize that this notion of categorization is socially defined; different cultures might categorize a certain object in different ways, or prefer to focus on its relationships rather than highlight its differences by putting it into a category. Thus, in some ways archives can tell us as much about the culture and time in which they were created as they can about the objects they contain. This culturally-specific categorization can act as a form of colonization, enforcing one culture’s world views on another, and encoding power structures within the archive.

The previous paragraph discusses how power can shape archives, and thus become embedded within in them. However, it is equally important to realize that archives themselves are powerful. Because archives preserve a selective view of the past, and are accepted as sources of knowledge about the past, they determine what is known and remembered. Consider this statement from the home page of Library and Archives Canada (LAC):

“As the custodian of our distant past and recent history, Library and Archives Canada (LAC) is a key resource for all Canadians who wish to gain a better understanding of who they are, individually and collectively. LAC acquires, processes, preserves and provides access to our documentary heritage and serves as the continuing memory of the Government of Canada and its institutions.” (LAC, November 2021).

To serve as the memory of a nation, and determine the identity of its citizens, is certainly a form of power!

It is important to note that none of this means that archives are inherently bad, or in any way unusable. However, Schwartz and Cook summarized the situation nicely when they wrote that “[w]hen power is denied, overlooked, or unchallenged, it is misleading at best and dangerous at worst. Power recognized becomes power that can be questioned, made accountable, and opened to transparent dialogue and enriched understanding” (2002). We hope that, throughout this course, you will begin to question previously unnoticed structures of power, and through that questioning, enrich your own understanding and research.

Comparing Archives

Since this is a course on the digital humanities, this lab will mainly discuss how to navigate various digital archives. However, you should also be aware that some digital archives are in fact digitized versions of physical archives. In this case, the holdings of the physical archive are likely to be more extensive than the online collection, since digitization requires both time and money, and tends to be an ongoing project.

Institutional Archives

Institutional archives, for the purposes of this lab, are those run by large organizations, such as universities, corporations, or governments. This section will focus on archives run by governments. Some jurisdictions might have multiple archives, run by different government institutions and serving different purposes. Canada’s national archive is run by Library and Archives Canada (LAC) [https://www.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/Pages/home.aspx]. At the time of writing, LAC is designing a new website, and once the new version is published the process for finding materials may change from the below instructions. Interestingly, they are also taking this opportunity to update outdated and offensive content. The LAC states:

Our current website contains information that was written many years ago. Unfortunately, it does not always reflect our diverse and multicultural country, often presenting only one side of Canada’s history. LAC acknowledges that some of its online presence is offensive and continues to correct these issues.

This is why content that is redundant or outdated will be removed or rewritten. Decisions for reviewing web content are based on various factors such as age of content, technology, resources and page visits. An “archived” notice will be placed on pages with older content that is still useful but will not be updated. In some cases, content may be removed from these pages.

Web content that provides evidence of LAC’s business activities is retained in our corporate repository according to Government of Canada information management specifications. LAC also manages the Web and Social Media Preservation Program, which archives and preserves websites. LAC’s websites are regularly captured through this program. (LAC, July 2021)

Do you think this is an appropriate approach to the problem? If not, how would you have chosen to address it?

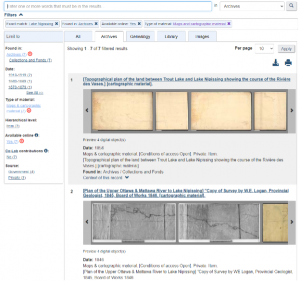

There are several different collections available for online search at LAC, and pages of resources for specific topics such as census data or military history. Generally speaking, however, a less focussed search will return the most results, and gives you the greatest opportunity to find information in places you might not have expected. In this example, we will look specifically for maps of Lake Nipissing, and explore one of our search results to see what kind of information is available in the online archive.

- You can carry out a general search from the Collection Search page [https://www.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/collectionsearch/Pages/collectionsearch.aspx].

- Click on the link which says “Advanced search”. This will allow you to specify exactly how your search terms should be used, narrow down the database you want to search, and select the year or time period of interest.

- As we are interested in archival material, set the “Search in:” menu to archives. There are other options; setting it to library, for example, would return records of books, which are usually not digitized.

- You have four options for entering your key words, and can use them in combination. Typing Lake Nipissing into the “All these words” search bar might return records about Lake Nipissing, but could also return records about people with the last name Nipissing, living near other lakes. The advantage of this is that it will also return records with similar words, in case a name is spelled differently in the record. Try it and see, if you like.

- If you would prefer only to see search results that match your search term exactly, you can type the word or phrase into the “This exact phrase” search bar.

- Once you click the search button, you will be brought to the results page. Notice that some of your results have preview images with them, while others do not. If you were looking for records to view at the archives, this would be fine. However, if you are looking for records to view online, you will probably be most interested in those with previews, which indicate a record has been digitized.

- You can use the sidebar at the left of the page to further restrict your results. For example, in the “Available online” section, click yes to see only those results that can be viewed through the website. In “Type of material”, you might like to limit your search to maps and cartographic material. However, sometimes the textual records can contain maps, so skimming through them can be a worthwhile endeavor if you have time.

- Let’s take a look at the “Plan of the Upper Ottawa & Mattawa River to Lake Nipissing”. When the search is set up as shown in figure 1, this will be your second result.

- Take this opportunity to scroll through the data available about this record. There is quite a lot of it, including information about where in the collection it’s stored (figure 2). This context can be important not only to tell you about the record and help you find similar items, but also to demonstrate how this particular archive is structured.

Community Archives

The term “community archive” is a broad one. In some usages, particularly in Canada, it refers to archives run by municipal or county governments. Many of these archives have not digitized their records; an example of one that has is the Community Archives of Belleville and Hastings County (CABHC) [https://www.cabhc.ca/en/index.aspx], who make their holdings available online through a variety of platforms, including the photo sharing site Flickr [https://www.flickr.com/photos/cabhc/]. Take a moment to explore their website and see how it differs from the LAC site.

- You can access the archive’s search using the “Discover our collections” button. This gives you access to a page with a search bar at the top left.

- For now, however, visit this map record as an example [https://discover.cabhc.ca/hydrographic-map-of-bay-of-quinte-picton-to-presquile-bay].

- Locate the archival context, which is in tree format at the top of the page. Do you prefer this to the static context tree from LAC?

- The record also includes links to related subjects, notes on the source, information about the file format, and some history of how the image has been used. These are provided as hyperlinks on the right side of the page. Do you find these more or less helpful than the context tree?

- Near the bottom of the page is a note that states “Revised on 13 May 2021 to redact the former name of the Narrows which contained a racist slur.” (CABHC, 2021). Consider again the question that was asked about the LAC’s stated approach to offensive content. Do you think this redaction with the addition of a note is the right approach? What others might you suggest?

In some other countries, a community archive is one run by a community organization, independent of government or other institutions such as universities. These archives are particularly interesting in that they are often run by groups who would not necessarily be considered a dominant power. Thus community archives can be a way to push back against the power structures of traditional archives, and particularly to prevent the erasure of marginalized groups. Some optional readings on this topic are included in Appendix 1.

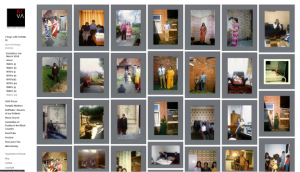

One example of this kind of community archive, from the UK, is the Apna Heritage Archive [https://www.bcva.info/about-2]. This archive is a community based and crowd-sourced photographic record of the Punjabi community in Wolverhampton. The Punjabi community is entirely missing from formal institutional archives in the region, and so a member of the community started a campaign to solicit family photos for digitization, to ensure the community would not be erased from local history. It was important to the organizers that the community retain control over these photos, so requests to change the associated metadata, or even to remove photos from the archive entirely, were always honored (Chhabra, 2021). The project is also unusual in its focus on family photos, rather than the formal documents found in many archives.

The digitized photos from the Apna archive will eventually be incorporated into the local government archives. At present, the records are stored on the Black Country Visible Arts website (figure 3).

- Take a look at an example [https://www.bcva.info/1980s-iii/ju7mfyxcxblrupflr3pxlnwkd4pm34].

- Note that there is considerably less data here than in the records from the LAC or CABHC. Why do you think this might be, and do you expect that it might change when the records are moved to the government archive? Would the structure of this archive change what it could be used for, and how that work would be done?

Spatial Archives

Since this course is specifically about spatial digital storytelling, it seems prudent to discuss spatial archives. For our purposes, a spatial archive is one in which the records belong to known locations, so that they can be mapped. The metadata of a spatial archival record will contain the coordinates of that record, and spatial archives are often searchable based on a map of records. Otherwise, however, they function as the previous archives discussed in this lab, and are just as varied.

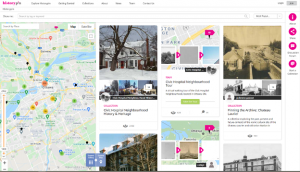

One spatial archive worth discussing is HistoryPin [https://www.historypin.org/en/], which in some respects could be described as a community archive. While it is run by a large non-profit organization, this website allows individuals to upload their own photos. Additionally, it includes images from the collections of many larger institutions. As such, it straddles the boundary between community and institutional, and even between archive and aggregation tool. This mixture of sources makes it an interesting place to contrast the way institutions and individuals tend to write about heritage, with different levels of formality and often for different purposes (Wagner, 2017).

Like most of the archives listed here, HistoryPin is relatively simple to use if you are used to search engines.

- Enter the name of your study area in the search bar. Keep in mind, larger cities are more likely to have records.

- The default interface has a map on one side, and a gallery on the other. As you zoom or pan around the map, the gallery updates to match the map area.

- You can also use the time slider at the left of the map to limit when the photos were taken.

- Clicking on a collection will show you all the photos that are part of that collection, while clicking an individual photo will show you that record, including its metadata.

- Take a look at these two records from Ottawa, one by a local historical society and one by an anonymous user. Is there a difference in the metadata between the two? Do you notice the difference in writing style that Wagner mentions?

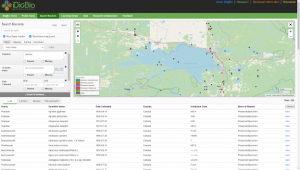

Another spatial archive of particular interest to environmental historians and geographers is iDigBio [https://www.idigbio.org/], which aggregates natural history specimens from institutions worldwide. Some are digitized while others are not; likewise, some have map points while others do not. The search interface on this site is more complicated than for HistoryPin (figure 4), and the metadata tends to focus on scientific terminology rather than narrative descriptions. At first glance, such a scientific archive might seem an odd choice to include in a humanities course. However, archives do not have to be used in the way that is most obvious. Because iDigBio includes information about who collected each specimen, and where, and when, it is possible to use it to study histories of collecting, not just biology and ecology. This is, in fact, the focus of an upcoming collaboration between Nipissing’s Centre for Understanding Semi-Peripheries [https://cusp.maps.arcgis.com/apps/MapSeries/index.html?appid=2625d059b3ab4325bb4700e47899de1e] and a number of community partners. Reimagining archives in this way opens up new and unique research possibilities, and also allows us to recognize and question the power of archives, as discussed in the introduction.

One thing to keep in mind about iDigBio is that many of the specimens were collected before the advent of GPS technology. Therefore records can have locations as unspecific as north shore of Lake Nipissing. While the associated map point will indeed end up on the north shore of the lake, this is quite a large area, and so the map points will not necessarily indicate the exact location where a specimen was collected.

- To search iDigBio, you will need to visit the portal [https://www.idigbio.org/portal/search].

- The search bar at the top allows you to search for a term in all fields. However, you can also search in specific fields, including scientific name, collection date, or institution. Not all of these fields are part of the search interface by default; some must be added using the “Add a field” drop down menu.

- You can limit your search by whether a record has an associated image, and whether it is mappable.

- The shape icons on the left of the map allow you to draw on the map. Only specimens collected within the shape you draw will be included in the results. The area of your search will be shown in the “Mapping” tab of the interface.

- You can download a spreadsheet of your search results at the “Download” tab.

- For now, take a look at this record, which is a typical example; be sure to scroll all the way down to get the full experience [https://www.idigbio.org/portal/records/66e31f19-3ff6-498f-8e1a-2e0f7d9feece]. Do you think the complex metadata is connected to the complex search interface? How does this compare to the amount of metadata that HistoryPin includes, and how the search on that website functions?

Other Archives of Interest

There are many, many digital archives now in existence, and it would be impossible to teach you how to use them all, or even to produce a comprehensive list. The examples above were chosen to illustrate the different structures of archives, and because they can prompt further reflection. If you would like to browse some others and explore further, the Toronto Public Library curates an excellent guide on finding archival images of Ontario, with many archives listed in it; many of these will also include textual documents [https://torontopubliclibrary.typepad.com/local-history-genealogy/2019/05/find-old-pictures-of-ontario.html].

Reading Archival Materials

Although this lab has focused mainly on navigating various kinds of archives in the literal sense, there are also some important considerations to make in metaphorically navigating the power structures of archives. Recall that we must first recognize power before we can account for it; doing so can help us to avoid further entrenching harmful power structures, or causing harm through other actions such as unintentionally perpetuating stereotypes. You may find it helpful, then, to ask yourself the following questions, both about the archive itself and the actual document you are working with, and to adjust your actions based on the answers you find. You should also keep in mind that these do not apply only to historical archives; it is just as necessary to think deeply about modern collections, and sometimes harder, since we are less distantly removed from their creation and use.

- Were the people represented in these materials the ones who created them? If not, who did?

- What was the original purpose of these materials?

- Why were these particular materials brought together in an archive?

- Was the archive created by the person or group who created the materials it contains?

- Who is the intended audience of the archive, and of the materials in it?

- How would any of the above questions impact how the materials are presented, and how you understand them?

Assignment

While this course does not include access to archival management software, it is still possible to go through many of the steps involved in creating a digital archival record. As such, please come up with an imaginary “archive”, and create three records for it. These should include both an object of some kind, and any associated metadata. The objects could be born-digital materials compiled from various places on the internet, represented by hyperlinks, or things you have digitized, represented by digital files of some kind. Submit a document including three records and associated metadata. This could be a text document or spreadsheet, but please keep it organized. Include with your submission a brief write up (no more than a page) about the considerations that went into creating your archive. You might like to use the following questions to guide you:

- Think about what kind archive you are creating records for. What is the theme or idea it is organized around? How would it be used? What kind of metadata would you need to include to support this goal?

- If you are including links to digital materials, how would you ensure those links did not change over time? If you are digitizing your own materials, what kind of file formats would you choose to ensure long-term readability?

- How do the considerations in the Archives and Power section influence your archive?

Additionally, this website [https://www.archives.norfolk.gov.uk/community-archives/about-the-toolkit] is a toolkit developed to help people start community archives. You may find some of the information, particularly about cataloging, useful in completing this assignment.

IMPORTANT: Please consider the privacy of individuals, and do not include materials that contain identifying information such as addresses, phone numbers, private social media profiles, etc. This kind of information should also be excluded from your metadata.

References

Textual References

Chhabra, Annand. “Punjabi Migration to the Black Country: A Photographic Journey Through History, Cultures and Digital Technology.” Presentation at the DigiCONFLICT Research Consortium online conference Photographic Digital Heritage: Institutions, Communities and the Political, October 19-20, 2021. https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLIz6EUVbWby-Wv6KLAMYByTGG4AWGErwe

Csank, Adam. “Learning to Read the More-than-Human Archives: Dendrochronology and ‘Talkative Trees’,” Network in Canadian History & Environment (March 3, 2021). Retrieved from: https://niche-canada.org/2021/03/03/learning-to-read-the-more-than-human-archives-dendrochronology-and-talkative-trees/

“Home,” Library and Archives Canada. Last modified November 9, 2021. https://www.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/Pages/home.aspx

Price, Kenneth. “Edition, Project, Database, Archive, Thematic Research Collection: What’s in a Name?” Digital Humanities Quarterly 3, no. 3 (2009). http://www.digitalhumanities.org/dhq/vol/3/3/000053/000053.html

Schwartz, Joan M. & Terry Cook. “Archives, Records, and Power: The Making of Modern Memory,” Archival Science 2 (2002): 1-19. DOI: 10.1007/BF02435628

Theimer, Kate. “Archives in Context and as Context,” Journal of Digital Humanities 1, no. 2 (2012). http://journalofdigitalhumanities.org/1-2/archives-in-context-and-as-context-by-kate-theimer/

Wagner, Karin. “The Personal versus the Institutional Voice in an Open Photographic Archive,” Archival Science 17 (2017): 247-266. DOI: 10.1007/s10502-016-9273-9.

“Web renewal initiative,” Library and Archives Canada. Last modified July 20, 2021. https://www.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/about-us/initiatives/Pages/web-renewal.aspx

Images

“Apna Heritage Archive 1980’s (iii),” Black Country Visual Arts. Accessed January 13, 2022. https://www.bcva.info/1980s-iii

“Item M420-2438 – Hydrographic Map of Bay of Quinte, Picton to Presqu’ile Bay,” Community Archives of Belleville and Hastings County. Revised on May 13, 2021. https://discover.cabhc.ca/hydrographic-map-of-bay-of-quinte-picton-to-presquile-bay

“Plan of the Upper Ottawa & Mattawa River to Lake Nipissing, Copy of Survey by W.E. Logan, Provincial Geologist, 1845, Board of Works 1846. cartographic material,” Library and Archives Canada. Last modified March 16, 2021. bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/CollectionSearch/Pages/record.aspx?app=fonandcol&IdNumber=4130165&new=-8585594990094781096

“Search Results,” HistoryPin. Accessed January 13, 2022. https://www.historypin.org/en/explore/geo/45.40487,-75.69849,12/bounds/45.285306,-75.80286,45.524181,-75.59412/paging/1

“Search Results,” iDigBio. Accessed January 13, 2022. https://www.idigbio.org/portal/search

“Search Results,” Library and Archives Canada. Accessed January 13, 2022. https://www.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/collectionsearch/Pages/collectionsearch.aspx?DataSource=Archives&OnlineCode=1&q_exact=Lake+Nipissing&start=0&num=10&TypeOfMaterialCode=600

Optional Readings

Digital Archives

“The Strategy,” National Heritage Digitization Strategy. Accessed January 13, 2022. https://nhds.ca/about/the-strategy/

“Digitisation,” Norfolk Record Office. Accessed January 13, 2022. https://www.archives.norfolk.gov.uk/community-archives/digitisation

Archives and Power

Taves Sheffield, Rebecka, Janet Ceja & Stanley H. Griffin. “Diversity, Recordkeeping, and Archivy,” The International Journal of Information, Diversity, & Inclusion 5, no. 1 (2021). DOI: 10.33137/ijidi.v5i1.36003.

Community Archives

Caswell, Michelle. “Seeing Yourself in History: Community Archives and the Fight Against Symbolic Annhihilation,” The Public Historian 36, no. 4 (2014): 26-37. DOI: 10.1525/tph.2014.36.4.26.

Flinn, Andrew. “Community Histories, Community Archives: Some Opportunities and Challenges,” Journal of the Society of Archivists 28, no. 2 (2007). DOI: 10.1080/00379810701611936.

Hurley, Grant. “Community Archives, Community Clouds: Enabling Digital Preservation for Small Archives,” Archivaria 81 (2016): 129-150. https://archivaria.ca/index.php/archivaria/article/view/13561

McCracken, Krista & Skylee-Storm Hogan. “Residential School Community Archives: Spaces of Trauma and Community Healing,” Journal of Critical Library and Information Studies 3 (2021). https://journals.litwinbooks.com/index.php/jclis/article/view/115/96