Exercise, Pt. 1: Mental Mapping

Before we go into some of the key questions for this module, we’d like you to draw a map of your campus from memory. Please do so now, using a blank piece of paper or a drawing app on your computer or phone. We will return to this exercise at the end of the module, but it is important that you draw it before continuing.

You can draw the map in any way you’d like. There is no right or wrong way to draw a map of your campus, even if you have never physically been there! If this is the case, you can draw a map of what you imagine your campus to look like, based on your own ideas as well as anything you might have been told or shown in the past.

No map will look the same even if it’s of the same place; the point is that place can be interpreted and represented in diverse ways. Despite the authority often communicated through maps, it is important to remember that all maps are subjective.

Historical research and storytelling in the digital age

Thinking about historical research and storytelling in the digital age involves a range of considerations, including but not limited to: historical research that uses digital methods for inquiry and data collection, historical narratives told through digital media, as well as histories of digital (and spatial) media, including the historical power relations that shape questions of digital access and impact. Digital practices and media respatialize research in methodological, conceptual, and practical ways. Questions about where research takes place (in the field, the archive, at home, and/or online, for example) and how phenomena or research materials travelare all shaped by the digital turn.

Indeed, historical research today is now inseparable from digital media, from research design to data collection to knowledge mobilization. The list of tools required to conduct and produce historical-spatial narratives has expanded to include computers, portable scanners, digital data and databases, reference/record management systems, GPS and mapping software, translators, the Worldwide Web (WWW), wifi, digital instruments and recorders, e-mail, and more. Indeed, very few research materials nowadays can be considered solelyanalogue – even within historical research, which values the physical, tactile materiality of archival objects (such as papers, photos, and instruments), analog materials are now mainly accessed first through a digital search. In cases where a physical finding aid is still available, there are often several digital steps before, during, and after accessing the hardcopy. These steps to locating physical materials increasingly happen online and off-site.

Maps are rich mediators of human-spatial information that can encode some version of a particular place or spatial relationship over time, but they must be scrutinized along lines mentioned earlier (perspective, orientation, authorship, political purpose, etc.). Stuart Dunn (2017, 90) notes that “[m]aps are simply one channel of conveying complex spatial clues about the formation of place in the human mind. This is an immediate challenge for the critical digitization of place derived from historical cartography.” To be sure, digitization, and the use of digitized materials in spatial humanities storytelling, is never a straightforward process. It poses new challenges and questions that require an understanding of historical, geographical, and political contexts that shape not only the creation and historical value of the research materials, but also the interpretation and communication of them today.

Although digitizing old maps in ways that retain their original traits (such as scales, projections, and symbology) can be a fruitful and educational exercise, spatial humanist Stuart Dunn exercises caution about simply replicatingthe material into digital format; at the very least, some contextual description is required. He uses the example of Ottoman Cyprus maps, which predated trigonometrical survey techniques. This meant that certain (east-west) planes were exaggerated while other (northern) parts of the island were flattened, and the (southern) coast that experienced ships transporting European travelers and cartographers was represented in much greater detail.

Decisions about whether or how to adjust for cartographic tools and techniques of the past are therefore important considerations for digital spatial humanities storytelling in the present. In addition to critical questions about authorship and audience, factors like preservation, accuracy, ownership, interactivity, repair, and longevity will also influence how digitization – and the use of digitized material in storytelling – occurs. As we will discuss further in Modules 3 and 4, it will also shape critical approaches to working with “born-digital” materials (that is, those that were created as digital in the first place).

These kinds of considerations, as well as their associated ethical concerns, will re-emerge throughout the course in modules and related practical activities. In the next section, we step back to consider the historical context shaping the newly emerged field of the geohumanities, asking: is it really that new?

Are the geohumanities as new as we think? Historical uses of spatial narratives

Drawing on Stuart Dunn’s work on the digitization of place, an important question posed throughout this course is: how was space mapped out in the past, and how do we understand it in the present?

To this we would add: how do we use digital methods available in the present to map (or tell other spatial stories about) the past?

These questions have been of interest to historical geographers for some time now but have been increasingly pursued by scholars across the digital and spatial humanities, including the more recently formed field of the geohumanities.

The term “geohumanities” emerged in the 2010s as a way of identifying the increasing engagement between the discipline of geography with theories and approaches across the arts and humanities. In the introduction to the first-ever issue of the journal GeoHumanities, geographer Tim Cresswell (2015) places this relatively new field of geohumanities within broader historical context to challenge the common assumption that geohumanities emerged with the digital and spatial turns (which we will discuss in more detail in Module 2) and the advent of GIS. The approach of combining what we might understand as “humanistic” questions about the peculiarities of place with “scientific” measurements and data production have a much longer intellectual history than is often recognized.

Engagement with the geohumanities necessitates historical inquiry into what geo- (“earth”) has entailed over millennia, from geography (earth writing) to geocoding and geovisualization. As Cresswell summarizes, this should include “the many traditions of predisciplinary, disciplinary, and interdisciplinary engagement with space, place, mobility, landscape, scale, and territory that have formed the foundation of our current interest in geohumanistic research and writing” (7).

The spatial or “geo-” humanities provide endless examples of how geographical concepts, such as earth, place, space, and landscape, can be woven into stories and, indeed, how they tell stories of their own. As Cresswell writes, it is important to acknowledge that place and space did not emerge as a philosophical topic during the spatial turn. Rather, spatial concerns were also at the centre of classical thought, noting that even Aristotle foregrounded place “because everything that exists must exist somewhere,” or, in Aristotle’s words: “because what is not is nowhere – where for instance is a goat-stag or a sphinx?” (4).

One example of geographical tools that have much deeper histories than typically acknowledged are latitude and longitude (lat/long) coordinate systems. While it is tempting for geographers to claim lat/long systems as a key and relatively recent contribution of their discipline, this is simply not the case. These locative systems, which are some of the most important measurements for georeferencing and widely embedded into a variety of digital locative media today, have been in place for millennia. As Cresswell writes, early efforts to measure the world into latitude and longitude existed well before academic thought became more strictly divided into distinct disciplines:

…the librarian of Alexandria, Eratosthenes, was busy measuring the earth and developing the system we now know as latitude and longitude that locates your every thought and move through your cell phone. He was a mathematician, geographer, poet, astronomer, and music theorist. (5)

Historical narratives today use an extensive collection of spatial media, old and new. Most of these are not primarily “geographical” tools, but nevertheless operate as spatial forms and are used widely across the geohumanities. Photographs, music (from song to wax cylinders to MP3s), paintings, film, audio recorders, dance, and written text, to name only a few, are all spatial materials that mediate storytelling, whether in digital or analogue format. This ability to spatially mediate knowledge is increasingly apparent (and often taken for granted) in digital contexts. Digital mapping and spatial analysis through GIS, for example, offers the capacity to not only enliven spatial storytelling through the layering of multimedia in both vector and raster form, but also to communicate complex spatial relationships and concepts such as mobility, connectivity, and interactivity. We will examine this potential further in the modules to come.

Ways of seeing: Colonial histories of (geo)visualizing landscape

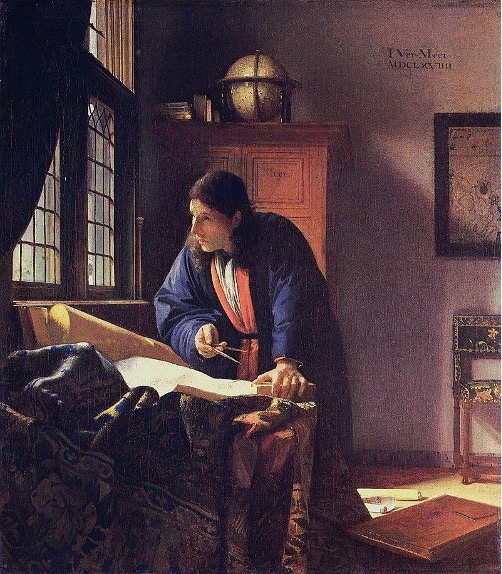

Figure 1: The Geographer, by Johannes Vermeer (c. 1668-69; public domain)

The cultural turn in the late twentieth century challenged taken-for-granted assumptions about “objective” knowledge and ushered in critical approaches to the representations (and contestation) of geographical concepts like place, landscape, nature, and culture. Landscape, in particular, became increasingly understood not just as something seen but as a “way of seeing.” The very notion of “landscape,” historical geographers explain, was developed throughout the fifteenth and sixteenth century. In Picturing Place, Schwartz and Ryan (2003) point to a shift in the Renaissance period toward linear perspective and mercantile capitalism and which, over the course of several centuries, led to techniques of visualization. This included the use of visual methods and imagery for the production of geographical knowledge and, more recently, the transformation of data into visual representations.

As a technique of visualization, cartography (digital or otherwise) must therefore always be situated within critical historical context as tools of colonization, capitalism, and patriarchy – the legacies of which we still see today, and which often intersect. For example, traditional mapping is often a tool of both colonialism and patriarchal relations through its tendency to reflect what feminist, poststructural, and postcolonial writers across the humanities, have called the “male gaze,” “white gaze,” and/or “the Western gaze” (indeed, the three often overlap, as expressed in author Toni Morrison’s work). The gaze in each sense refers to particular “ways of seeing” that privilege an all-male, -white, or -Western perspective and that may make similar presumptions about the audience (Bender, 2003). This has led to the marginalization, objectification, sexualization, or infantilization of communities (e.g. women, non-Western, people of colour). In cartography, the gaze (in any of the senses above) has led to the exploitation of land and people, often through the manipulation of cartographic techniques to render particular people, places, and worldviews inferior to those privileged by the gaze.

Perspective is indeed a major theme across the humanities. Historical geographers have asked important questions about how past and present tools of geo-visualization shape perceptions of place, space, and landscape, and the degrees to which such topics can ever truly be known. As Schwartz and Ryan (2003) write, “the conventional visual devices and technologies of geography, such as the map, have been scrutinized in the light of questions about perspective, orientation and cultural context.” Such scrutiny must also include considering who (people, institutions, etc.) has the power to define maps as authoritative geographical texts in the first place, as well as what “counts” as a map, or is accepted as a legal representation of land.

Visualizing Colonial Cartographies of “Canada”

One historic example through which dominant, Eurocentric conceptualizations of land title and rights were challenged can be found in the Delgamuukw v British Columbia case (1997). First held at the British Columbia Supreme Court and later appealed through the Supreme Court of Canada, the case was concerned with the definition and scope of Aboriginal title and has since shaped other court cases regarding Aboriginal title and rights. The case was also the first of its kind in Canadian courts to affirm the validity of oral history as part of land claim testimony. This oral testimony included not only speaking but also singingthe land, which challenged colonial ways of signifying territory or documenting place-based histories such as land surveys, maps, and written documents.

However, the power imbalances that already existed due to the location and oversight of the trial (occurring in a colonial court with a Canadian judge), the prioritizing of English language, and the deeply entrenched Eurocentricity shaping how land is defined in Canada, were further demonstrated in the judge’s flippant attitude toward oral tradition. An example of this has been memorialized as a cartoon (drawn by Don Monet) depicting a moment in the British Columbia Supreme Court during which Judge McEachern claimed to have a “tin ear” regarding oral testimony, directed at the Gitxsan and Wet’suwet’en elders speaking and singing about deep historical relationships with the land (for an article about the case, as well as one of Monet’s cartoons, see Anderson 2011).

In Canada, mapping has been dominated by a relatively small group of elite individuals and institutions who often meet some combination of the following characteristics: white, Eurocentric, cis-male, able-bodied, English-speaking, and upper socioeconomic communities. Most maps of Canada feature English (and to a lesser extent, French) language and places named for European colonizers despite the well-documented fact that Indigenous people lived on and named different parts of the land for tens of thousands of years before Europeans arrived. For hundreds of years, for example, the Anishinaabeg (and other First Nation peoples) used birchbark scrolls as a form of wayfinding and relating to land. Eurocentric place names in what is now Canada erase longstanding Indigenous names that tended to feature rich and informative descriptions of those places. Cartographic erasure therefore includes the displacement of traditional languages, including those of landforms and other environmental indicators, such as botanical names and gikendaasowin(knowledge; see Geniusz, 2009).

The power of authorship and persuasion has lasting implications for how Canada is conceptualized, placed, protected, and contested today. To be clear, this widespread focus on visual, Eurocentric, and white knowledge production – historically connected to colonial representations of land and specifically property– occurred long before the advent of digital technologies. However, visualization has extended into the digital realm, bringing with it past assumptions about visual knowledges while also carving out new, data-based notions of what can be visualized and how. As Dallas Hunt and Shaun Stevenson (2017, 3) explain:

Whether through traditional topographic mapping, or increasingly advanced digital data-based mapping processes such as Geographic Information System (GIS) mapping, geographical knowledge continues to be produced, acquired and imposed as a fundamental technique of shoring up dominant conceptualizations of the Canadian landscape.

As we will address throughout the course, the legacies of colonialism endure in implicit and explicit ways, in large part through maps and other geovisual media, which have lasting implications for how “Canada” is conceptualized today. Historians and geographers, in particular, must recognize their own colonial inheritances coming from disciplines that actively assisted in colonization and imperialism (for example, through exploring, surveying, mapping, collecting, archiving, writing, and recording). However, the proliferation of digital spatial media – including increased accessibility, relative affordability, and portability – have also led to new opportunities for “re-storying place” and creating more polyvocal spatial narratives.

Conclusion: Toward Critical Cartographies

As we have introduced in this module, and will discuss further in the Spatial Archives module, the use of maps to advance colonization (which is also connected to capitalist and patriarchal systems of power) is well documented. Maps have long been tools that helped dominant groups demarcate, claim, marginalize, exclude, legalize, criminalize, erase, silence, legitimize, and standardize. Symbology and language play a major role in perpetuating colonial narratives, with dominant languages being used to re-write place.

It is not merely that spatial media (maps or images) showspace; they also actively reorganizeand produce space. Put another way, maps (and the actors involved in map-making) have the power to build and change worlds, in addition to representing them. We will return repeatedly to questions about the power relations involved in geovisual methods of storytelling, including mapping, digital archival research, and GIS. Doing so draws on approaches of critical cartographythrough a focus on the relationships between power and geographical knowledge (Crampton and Krygier, 2005). Such an approach encourages scholars to pose critical questions about, to, and ofcartographic texts and techniques. We will also consider how critical and community-based cartographic approaches are also being employed to expose, challenge, or decolonize the very structures that have led to social injustice.

In the next module, we will delve deeper into the digital and spatial turns that have shaped digital spatial storytelling today. To complete the module, please move ahead to Part 2 of the Mental Mapping exercise, which invites a reflection based on several questions about the map you drew at the outset.