Historical Research and Storytelling Through “GLAMs”

What are GLAMs?

GLAM institutions (galleries, libraries, archives, and museums) are creative spaces of cultural heritage preservation, record management, and valuable sites for accessing knowledge in material and digital forms. One common characteristic is that these spaces are often said to be maintained in the public interest; however, it is also important to note that public in this sense does not mean equally accessible or free to everyone. Although GLAMs often share characteristics of preserving cultural heritage, research- and arts-based institutions, and sites of record-keeping, they do differ in other ways. These differences, some more subtle or obscured than others, might include: underlying infrastructure, core principles, level of interaction with the public, protection and accessibility of materials, curatorial power, core values, and funding models. Some of these are more subtle or obscured than others.

Below is a brief overview of some distinguishing characteristics, which should be read as partial and dynamic, particularly when considering how (or whether) digitization and other digital media practices have changed the dominant classifications of GLAMs over time.

Galleries are curator-driven and highly selective, with a primary focus on various forms of art (visual art, sound installations, textiles, and so on). Like other GLAM institutions, galleries are rapidly changing with the rise of digital technologies and digital (or crypto) currency that reimagine the meaning and value of art, collection, collector, ownership, and domain.

Libraries tend to take in and provide access to individual items, including digital and analogue media such as books, audiovisual materials, and maps. Libraries tend to be more user-driven and items are generally available to the public (although often require registration and come with borrowing privileges or digital licensing). Many digital libraries are also user-driven and sometimes crowd-sourced, with some vetting from the institutions before making records available.

Archivestypically house more “complete” groups of works that are chosen under relatively strict archival acquisition policy. Preserving context of the collection is a major focus for archives, including regard for provenance. Access to archives tends to be more restricted, although this has changed to some extent with the digitization of archival materials and born-digital data.

Museumsare cultural heritage institutions that collect specific objects for public display, while also storing and preserving artifacts not on display. Museums often rotate public-facing collections and are more likely to respond to public interest of the moment. Curators occupy an important position, providing context for the displays.

In the required reading for this module, archivist Kate Theimer (2012) discusses the need to better contextualize the histories of GLAM institutions to avoid flattening the distinctions between them or perpetuating misunderstandings between trained archivists and scholars theorizing archives in the digital humanities. Indeed, these distinctions and histories are important; however, it should also be recognized that GLAM institutions are increasingly blurred by digital technologies and spatialities, and not all sites of cultural heritage production fit neatly into one or any category.

For example, museums often have archives and libraries may feature a gallery or (more restricted) special collections. Botanical gardensand zoosshare many of the same characteristics as GLAMs (indeed, they are often extensions of museums or galleries and are carefully “curated” in some form), but could likely be considered their own category. Instead of the preserved, dead “specimens” one might find in a museum or botanical library, botanical gardens and zoos contain living, breathing beings (e.g., plants and animals) that are often accompanied by plaques with botanical, zoological, geographical, and/or historical information. Finally, it could also be said that universities are also GLAM spaces, as sites that host, contribute to, and whose teaching and research are informed by GLAMs.

Turning the lens on GLAMs

The cultural turn sparked a more directed focus on GLAMs not just as sources of research materials but as objects and spaces that are themselves worthy of critical inquiry. Archives were heavily studied in the 1970s-1990s. Jacques Derrida wrote that “nothing is less clear today than the word ‘archive'” (1995: 4). Given the term’s uptake across fields like history, archaeology, bibliography, and philosophy (among others), Derrida advocated for an interdisciplinary science of the archive (Manoff, 2004). Another philosopher, Michel Foucault, wrote extensively about the discursive, knowledge-power relationships that have built and shaped the ongoing production of societal institutions like archives and museums (see Foucault 1972). He situated them within other forms of institutional and discursive power relations (e.g., disciplinary and carceral power structures that also characterize schools and prisons).

Archival and museum studies, therefore, are as much about studying the ways GLAMs have been conceptualized, created, and contested, as they are about studying the materials and cultural practices within GLAM spaces. Included in the study of GLAM spaces is the understanding of how these sites are place-based: they are all located somewhere (often many places at once, including digital, online, and physical spaces); they all collect materials from somewhere (and the collections often represent selected places and locations); they all actively makeplace and create new spatialities in their everyday production; and they highlight the interconnectedness of many places at once. These considerations of place are heightened by the dynamics of the digital.

As we will expand upon for the accompanying lab using the example of archives, scale and scope of GLAMs are also important place-based considerations. Although many different archives might share underlying principles, it is important to consider how the scale and scope of an archive shapes the knowledges preserved, produced, and circulated. These factors contribute to the political character of archives at any scale. National archives, for example, may receive public funding or are more likely to receive large-scale donated collections in the name of preserving national public memory and, often implicitly, upholding values of the nation-state. Local or community-based archives might still receive some public funding, but their pockets are typically not as deep. Community archives are also more likely to have a more focused agenda based on cultural characteristics of that specific community. Digital technologies have expanded the reach and scope of particular kinds of archives and other GLAM institutions. This is particularly important for relatively small or local organizations with limited physical storage, but increased digital storage and sharing capacities.

Colonial and imperial legacies of GLAMs

GLAM institutions have been studied as spatial extensions of the imperial states and colonial rule. All are real and imagined terrains of cultural politics; they are physical, material, digital, affective, discursive, political, and bureaucratic spaces with a reach that extends far beyond the physical location of records. As Ann Laura Stoler writes: “Colonial archives were both sites of the imaginary and institutions that fashioned histories as they concealed, revealed, and reproduced the power of the state.” (Stoler, 2002: 97). Rather than just conceptualizing archives as sites of historical knowledge retrieval, Stoler reminds readers that it is equally, if not more, important to understand archives as sites of knowledge production.

Although it can be argued that archives have existed in various forms for millennia, what has now become known as traditional, colonial, and imperial archives are most often attributed to the Age of Empiricism, which foregrounded numerical representation, order, management, and scientific knowledge production. Archives at this time were built to further entrench imperial and colonial values, social order, and thus power, into everyday societies. Depending on the institution, this might not necessarily be as evident through record acquisition, as many archivists do not actively solicit and select specific collections, but record maintenance and dissemination are also ways in which power is exercised.

All GLAMs include some kind of collections or repositories, and it is important to understand the important role of collecting in the colonization of place. Recognizing the archive as a spatial extension of colonialism includes examining the histories of collecting that led to the acquisition (or accession) of archival material. Collecting is a political act, and one that was exercised primarily by explorers and anthropologists representing colonial and imperial authorities. Many collections in GLAMs today are comprised of materials that were taken without permission, or without effective communication of how and where a community’s cultural heritage objects would travel. In most cases, the items were never returned, forming an individual or institutional collection that was later donated or sold to GLAMs. Some of these include human remains, funerary objects, and cultural patrimony or sacred objects. However, many GLAM institutions have since begun to form repatriation policies to address and repair these fraught histories, such as the Royal Ontario Museum (ROM), the Smithsonian Institution, and the Chicago Field Museum (the latter of which we will discuss later in the module.

Even if we accept the more traditional purpose of archives to preserve materials in their original context (often unconsciously created and thus not as selective as other collections), important questions about how it came to be that a particular institution or person’s records over others were available to archivists remains important. Although this is not always clear, some clues can be found in the archival record (for example, donated by a family member). Key questions follow: under what conditions, and by whom, are records shared with archives (and museums, galleries, and libraries)? What kinds of truth-claims are present not just in the records themselves but in their maintenance, protection, and presentation? What kinds of materials held in archives are considered more legitimate historical “evidence?” The answers may be obscured in the infrastructure of the space, but they remain important considerations for critical research and storytelling.

Digital GLAM-up? How galleries, libraries, archives and museums have shifted in the digital era (and through a global pandemic)

GLAM institutions have shifted considerably in the digital age, in some cases out of their own volition and in other cases propelled by other technological and societal change. The following subsections offer some examples of, and factors behind, these changes. They are by no means exhaustive and are likely to change over the coming years; we encourage you to consider other ways GLAMs have pivoted or been reimagined through the digital age. At the end of this module (see Appendix), you will find a list of digital history projects and platforms that may provide inspiration for your own digital spatial humanities work.

Global Pandemic (2020-)

Before the Covid-19 global pandemic, most museums and other GLAM institutions with access to necessary funding and resources had already begun a shift toward digital engagement with various aspects of cultural heritage management, including materials, records, collections, audiences, partnerships, and outreach. This shift, shaped by digital, cultural, and spatial turns, has occurred for many reasons, including decreases in visitors’ attendance at GLAMs, the cost of preserving and displaying materials, greater understandings of accessibility needs, and human-led climate change with its associated increase in environmental disasters like wildfires that threaten GLAM infrastructure and collections. Until recently, however, the process of GLAMs “going digital” was a relatively slow (and perhaps more careful, selective) experience. The global pandemic, which began in 2020 and which led to new public health measures such as isolation and vaccine mandates for accessing particular spaces, rapidly accelerated the push to create a stronger digital presence. Of course, this has transformed how people access, experience, and use GLAM materials and data, as well as the storytelling opportunities that emerge.

Reliance on personal, mobile, digital technologies

Smartphones, personal computers, and at-home Internet connections have become vital technologies for expanding the reach of GLAMs’ physical buildings as well as their collections and databases. Likewise, personal digital devices offer the potential for individuals to “enter” the spaces of museums, albeit in less traditional ways. In both cases, digital technologies, particularly in combination with mobile devices, respatializethe experiences and impact of museums. Indeed, museum staff have relied heavily on the assumption that most people have access to, and know how to use, smartphones and tablets to conduct research or experience an exhibit online. Such an assumption is understandable based on the increasing reliance on smartphones and personal computers; however, as always, it must also be situated within geographical and socioeconomic context. Digital divides shaping accessibility and usage (of digital technologies, information, and services) indicate that the digital reach of GLAMs might not be as ubiquitous as it is assumed.

Preserving digital histories: The Wayback Machine

The Wayback Machine is the largest publicly accessible archive system in the world (Bowyer, 2021). It was developed to allow users to “go back in time,” responding to the challenge of losing, displacing, or forgetting content when websites are updated or shut down. The Machine is stored on a cluster of Linux nodes housed by the Internet Archive (a digital library offering free, public access to digital materials) and uses Internet bots (often referred to as “crawlers” or “spiders”) to locate and download publicly accessible information on webpages. With the kinds of services and capacities required, there is a lag time that exists between “crawling” and making data publicly accessible; however, what once took several months (in 2014) to make public now only takes a few hours. In addition to using the Wayback Machine as a research tool, the history of the Wayback Machine is itself of interest to digital humanities scholars – even the name refers to a fictional time-traveling device in The Adventures of Rocky and Bullwinkle and Friends!

Born-digital media and the changing values of digital cultural heritage

There are several important questions about the records stored in digital archives, which will determine how those archives can be used. Other questions arise regarding the value of particular aspects of digital records. For example, are digital records only important for their contents, or are they are artefacts in and of themselves? This is particularly salient for born-digital materials; if they are important as artefacts, then it is important to preserve the original file types, even if this results in difficulties surrounding obsolete software. However, if the contents of digital files are the overwhelming concern, then it may be preferable to ensure accessibility by choosing file types that can be used in a wide range of software and which don’t change much over time. Furthermore, are digital records most important individually or in aggregate? The former would result in digital archives that are best used in the same way as physical archives, with researchers reading individual texts. The latter possibility, however, is linked to the advent of the digital humanities, where computing techniques can be applied to analyze materials in much larger volumes than traditional techniques. In all cases, context matters.

Born-digital GLAMs, and digital art more broadly, have changed the relationships between production and consumption, artists and audiences, curators and the curated, and makers and collectors, among other blurred boundaries too vast to list here. Digital technologies enable a reimagining of how GLAM materials are created and shared, and challenge traditional archival principles of provenance, accession, and ownership. Although context remains an important topic for how GLAM materials are managed and understood, the context of born-digital collections introduce new complexities. This is true not just of the technologies that create digital GLAM materials but also of the technologies that market them, such as the rise of non-fungible tokens (NFT) and crypto currency (see Valeonti et al., 2021).

In a world where monetization is rapidly changing, there are indeed new contexts around the (cultural and economic) value of digital GLAMs and their materials, new meanings of collectors and collections, and ever-changing potential for storytelling in the digital humanities. Initiatives like OpenGLAM, which was led by the Rijksmuseum (Netherlands) promote free and open access to digitized GLAM collections. This is done in part by encouraging institutions to avoid putting any new rights on artefacts that were previously in the public domain (using legal tools like Creative Commons Zero Waiver) and to publish files in open file formats (OpenGLAM.org). The barrier-free promise of OpenGLAM creates new forms of access but has also been challenged, with scholars pointing to new forms of barriers, including “image quality, image tracking and the difficulty of distinguishing open images from those that are bound by copyright” (Valeonti, Terras, and Hudson-Smith, 2020).

Interconnectivity between GLAM spaces, collections, and interfaces

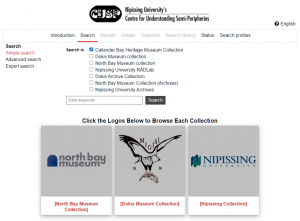

Advancements in digital media have led to multi-institutional and cross-cultural interconnectivity across collections, making it easier to share archival materials across multiple spaces, including across institutions and communities. One example of this is Nipissing University’s “Near-North CUSP Collections” (Fig. 1) an e-collections database hosted through Axiell‘s collections management software. The database was designed to “make accessible regional collections into one online platform for researchers and the general public, and to provide research into provincial, national and international museum and archival collections on materials relevant to the region” (Nipissing University Centre for Understanding Semi-Peripheries, 2021). In module 6, we will discuss how such interconnectivity promotes new collaborations and potentially more reciprocal research relationships (Hennessy, 2016). These include relationships between universities, communities, and GLAM institutions across Anishinaabeg territory.