Feedback, Practice, Metacognition

Giulia Forsythe

Feedback and Practice

The principle of goal-directed practice and feedback refers to students needing numerous opportunities to work toward the goals that have been set and to receive explicit feedback. Feedback is most effective when it is provided at the right time for the learner. Often we design our assessments at the end of the learning to measure the final product, and we do not provide sufficient opportunities to scaffold learners toward the goal. The latter is known as formative assessment and can be immensely beneficial to you as a teacher in determining if your learners are on track. It is even more important for your learners to discover for themselves how well they are doing and how they can improve in particular areas.

In-class strategies

Here are some strategies for applying formative assessments:

- Use the “one-minute paper.” Ask your students to write on an index card (or the equivalent online document) what their most significant learning was for a lesson, module, or even a lecture.

- When the goal is acquisition of factual knowledge, chunk your assessments into smaller, more frequent quizzes to allow students the opportunity of experiencing test-taking in a setting with lower stakes than the typical midterm exam.

- When creating written assignments, consider designing the assessment to include draft revisions. This could be done by frequent writing activities in discussion board forums, creating an annotated bibliography, using mind maps, or asking for weekly reflections.

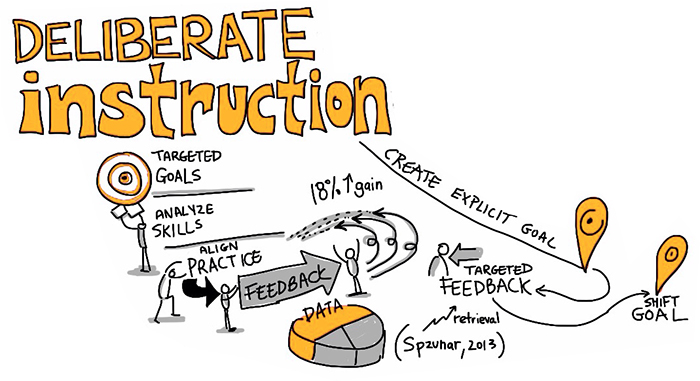

Deliberate instruction is the act of always considering your desired outcome and intended learning for your students, and then working backwards in your lesson planning so that students can successfully achieve that goal.

Climate of the Course

The social, emotional, and intellectual climate of the course and the classroom has an impact on learning. You can promote positive climate in your classroom by:

- Providing opportunities for small-group learning and interaction.

- Listening carefully.

- Offering opportunities to be heard.

- Providing an environment that makes uncertainty safe.

- Examining your assumptions.

- Being respectful and inclusive.

- Considering cognitive, psychomotor, and affective domains.

These factors that promote a healthy classroom climate will vary depending on the people involved. It’s always best to establish ground rules for your class right from the outset so that the classroom climate standards are co-constructed and meaningful to the group as a whole.

What does a positive classroom climate look like online? As you will see in other modules, the Community of Inquiry is a helpful framework. Beyond just presentation of content, described as the “cognitive presence,” it is also important to balance and consider social and teaching presences.

Extend Activity – Please Allow Me To Introduce My Field

Create an introductory activity connected to your discipline to get to know your learners.

For example:

- In a human geography class you could ask every student to describe their favourite place.

- For earth science the question could be “What mineral would you be based on hardness? Why?”

- For English literature, each student could discuss what fictional character they would like to invite to dinner, and why.

- In history, ask what figure, living or dead, would be the most interesting to have at a cocktail party?

Can you think of some fun and interesting questions for your discipline?

See some examples done by previous Extend participants.

Metacognition

Students need to assess the demands of the task, evaluate their own knowledge and skills, plan their progress, monitor their progress, and adjust their strategies as needed.

Self-directed learning and actively taking the time to reflect on one’s own learning is described as metacognition. Developing metacognitive skills through deliberate practice and embedded checkpoints fosters intellectual habits that are valuable across disciplines.

These checkpoints should occur at the beginning of the learning where students are encouraged to practice task assessment and planning. Metacognition should continue through the evaluation of the outcomes and adjust approaches accordingly.

A very important factor for developing this flexible mindset is rooted in students’ self-efficacy. It is extremely useful for instructors to stress the importance of developmental approaches so that they can fully appreciate that intelligence is not fixed.

Strategies to promote metacognition

- Be explicit; indicate what you don’t want; provide performance criteria.

- Provide opportunities to peer and self-assess; practice; and give feedback.

- Ask your students whether the answer they provide is reasonable given the problem.

Here are some helpful prompts to ask your learners:

- What do I already know about this topic?

- How does this topic make me feel?

- Does this topic relate to something I already know?

One activity that can be done at the end of class is Stephen Brookfield’s critical incident questionnaire (CIQ).

Other metacognitive strategies that lead to self-directed learners are Note-taking (see organization), One Minute Paper (see feedback and practice), Reflective Writing (nuggets), Exam Wrappers, and Retrospective Post-Assessment.

Extend Activity – Thought Vectors

This activity is taken from the Thought Vectors connected course designed by Dr. Gardner Campbell.

Find a nugget in a reading. Check out the Faculty Patchbook and select an article that resonates with you. Take a single passage from the article that grabs you in some way and make that passage as meaningful as possible.

It could be a passage that puzzles you, or intrigues you, or resonates strongly with you. It could be a passage you agree with, or one you disagree with. The idea here is that the passage evokes some kind of response in you, one that makes you want to work with the passage to make it just as meaningful as possible. A good length for your nugget is about a paragraph or so. Too much, and it becomes unwieldy. Too little, and you don’t have enough to work with.

How do you make something as meaningful as possible? Well, use your imagination. You’ll probably start by copying and pasting the nugget. Or if you’re feeling very multimedia inclined, read your nugget aloud and make an audio file. From there, consider hyperlinks, illustrations, video clips, animated gifs, screenshots, whatever. Make the experience as rich and interesting as you can.

Obviously, one of the main goals of this assignment is to get you to read carefully and respond imaginatively. Your work with “nuggets” should be both fun and in earnest. It should demonstrate your own deep engagement and stimulate deep engagement for your reader as well.

What “nugget” from the Faculty Patchbook resonated with you?

See some examples done by previous Extend participants.