Economies prior to the late 20th Century

During the 1870s, the traditional way of life of Plains Peoples became less and less possible. For one thing, the bison were rapidly disappearing. First Nations were losing their main source of food, clothing, footwear, and shelter. A culture grounded in bison hunting was losing its organizing principle.

Secondly, settlers were arriving in great numbers. As police did not exist in western Canada until 1874, when the Northwest Mounted Police (today’s RCMP) arrived, and since the area was weeks away from Ottawa, a “Wild West” culture of lawlessness that had characterized the later fur trade continued to threaten Indigenous well-being.

Writes Daschuk (2013), “Predations against First Nations are well documented in the years before the arrival of Canadian law in the west in 1874. The grisly murder of Kainai chief Calf Shirt, and the massacres of Assiniboines at the Sweet Grass and Cypress Hills, are bloody examples. Occasionally, First Nations turned on their neighbours in the increasingly desperate and hostile environment of the northern plains.”

The government of Canada could hardly control the western movement of settlers, and anyway it was eager to expand the nation from Sea to Sea as proclaimed in Canada’s motto Ad Mare Usque Ad Mare.[1] The map below shows how isolated British Columbia was from Eastern Canada in 1871. British Columbia had finally joined Confederation based on the promise that a railway would be built to connect it to Eastern Canada within 10 years.

As explained by the Canadian Encyclopedia, the young Canada established itself, and bolstered itself against potential American ambitions, by building the Canadian Pacific Railway from North Bay, Ontario to Port Moody, British Columbia, and settling towns along the railroad’s path.

While settlers often crowded out or pushed out First Nations, the Canadian government itself appeared to follow the correct procedure to acquire land for settlement. As mandated by King George’s Royal Proclamation made a century earlier, the Crown negotiated treaties to obtain Indigenous land, then provided this land to the railway.

In the context of Euro-Canadian settlement and the disappearance of bison, First Nations of the Plains were under heavy pressure to sign treaties that might provide a small but secure land base, some economic development assistance, and some protection from famine and illness.

Ever since the Royal Proclamation of 1763, the British had been arranging treaties with First Nations in order to acquire land for European settlement. This process usually involved setting aside land, called reserves, for the exclusive use of the First Nation. In fact, land had been set aside for First Nations in Eastern Canada as early as 1637. Different reserves were governed in different ways until the Indian Act (1876) was passed to regulate all reserves.

The Numbered Treaties 1871 + :

The treaty-making and reservation process which secured Indigenous land for the railway and for settlement was welcomed – in principle – by many of the First Nations involved. First Nations were concerned about what so many settlers meant for their way of life and for their personal safety. They were also unsure how they would manage without bison and hoped that treaties would come with some form of assistance for transitioning to agriculture.

Treaty 1 was signed in 1871 between Canada and the Anishinaabe and Swampy Cree living in southern Manitoba.

After this, the Numbered Treaties moved roughly east to west and south to north, ending with the adhesion to Treaty 9 in northern Ontario in 1929-30. The map below shows all the treaties that existed prior to 1975. You can see that the land covered by the Numbered Treaties far exceeded previously treated land and comprised almost half of Canada’s land mass.

The signatories of Treaty 1 were concerned about receiving assistance to transition to agriculture. According to the Canadian Encyclopedia, one of their representatives felt it unfair that the acreage per individual would be similar to the amount granted to white settlers, since First Nations had no money or tools with which to farm.

The Anishinaabe and Cree of Treaty 1 ended up ceding a huge part of southern Manitoba – including the Red River Valley and what is now Winnipeg – in exchange for 160 acres for each family of five, $3 per person per year, and a school with teachers. No mention of agricultural support was included in the written version of the Treaty, but after the Anishinaabe and Cree complained about not seeing what they were promised verbally, the Treaty was eventually modified to include animals and equipment. Recall that this treaty was signed two years after the Red River Resistance and the formation of Manitoba. Métis rights were to be delivered through the Manitoba Act; the Métis were not part of the Numbered Treaty process.

The Salteaux involved in Treaty 3 rejected two draft treaties until they received a promise of agricultural assistance, and all subsequent Numbered Treaties included gifts of farm tools and farm animals. The gifts were not lavish. In the case of Treaty Four, the band was to be given one square mile, two hoes, one spade, one scythe, and one axe per family of five. Every ten families would get a plough and two harrows, and every Chief would get one yoke of oxen, one bull, four cows, a chest of carpenter’s tools, five hand-saws, five augers, one cross-cut saw, files, and a grindstone.

A new provision in Treaty 6 was the provision that the Indian Agent, the local official representing the federal government to the Band, would keep a “medicine chest” for the benefit of the community. This has been interpreted as an obligation on the part of the federal government to provide health care to First Nations. Over time, these various obligations – education, health care, economic development support – have become standard for all reserve communities across Canada.

Note that the Numbered Treaties were all negotiated without proper legal representation of the First Nations involved. Translation too may have been an issue. Many First Nations have argued that the written Treaties leave out guarantees that were made verbally, guarantees of hunting and fishing privileges outside the reserve’s boundaries. They argue that mineral rights were never part of the deal; despite Treaty texts indicating that First Nations were giving up “all their rights, titles, and privileges, whatsoever, to the lands included…”(Treaty 6), First Nations recall understanding that the land would be used for agriculture to the depth of a plow. From that point of view, they should have been consulted when, in 1930, Canada awarded Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and Alberta rights to the natural resources within their provincial boundaries.

[2]

Writes former Siksika Nation Chief Leroy Paul Wolf Collar, “Although some people suggest that the treaties were land surrenders, First Nations disagree. They contend that their grandfathers, who were signatories to the historic treaties, did not receive such an understanding from the treaty talks, never gave up their inherent right to the lands and resources, and did not give up their right to govern themselves.” [3]

The Treaty Commissioners did not warn the First Nations of Treaty 7 (1877), Treaty 8 (1899), and later treaties that their reserves and economic activity would soon be subject to federal government control as per the Indian Act (1876). “So all the while… government officials appeared to negotiate the treaties in good faith, they had, in fact, withheld information about the Indian Act.” [4]

For the next one hundred and fifty years, Canada and the provinces would allow development on treaty land, with virtually all the profits going to non-Indigenous persons and companies. On Blueberry First Nation territory within Treaty 8, two hydroelectric dams were built, causing land to be flooded and river flow to be reduced; a third dam, known as “Site C”, was being constructed in 2021. Sixty-nine percent of Blueberry First Nation territory was held by oil and gas companies. [5]. In 2021 the British Columbia Supreme Court ruled that the province had violated Treaty 8 by allowing so much industrial development on Blueberry territory that the band’s hunting, gathering, and fishing were severely impacted; henceforth, consent of the band must be obtained.[6]

Blueberry First Nation is a small First Nation, with a total of 485 people at the time of this verdict. Its traditional territory is 38,000 square km. Legal rights, however, do not depend on the size and power of the signatory. And we might ask ourselves how large Blueberry First Nation might be today if its rights had been maintained these last two hundred years.

Involuntary Reservation:

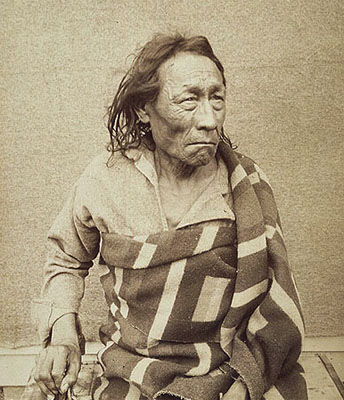

Though many First Nations leaders were ready to participate in treaty-making, even if that involved a reserve, others wanted nothing to do with the process. One of these, Cree Chief Big Bear, held off joining other Cree in Treaty 6 for six years. He eventually signed on due to hunger, but refused to choose a reserve.

Daschuk (2013), in his prize-winning book Clearing the Plains, documents how the federal government used hunger to break the independence of Plains First Nations. Starvation was already an issue in the signing of Treaty 4 in 1874.

In the United States, where treaties were not being made, several epic battles, massacres, and mass deportations resulted from the attempt by the US Army to control and confine First Nations. Some of these tribes moved to Canada. Today there is still a close relationship between communities on each side of the border.

Problems with Agriculture:

Once First Nations were on reserve, they found that they were worse off in several ways. First, the reserves were much smaller than their traditional territories, so could not support traditional hunting, fishing, and trapping. Reserves were also unlikely to be prime agricultural land. First Nations could not sell this land and move to better land, or land closer to markets.

If they moved off the reserve, they moved without land and without any assistance from government. Not only that, but between 1889 and 1930 Indigenous people on the Canadian Plains and elsewhere were literally forbidden to leave their reserves without a pass given by the Indian Agent appointed to administer their reserve. Government became more and more controlling. First Nations also found that their attempts to adopt agriculture were thwarted. While officially the federal government promoted agriculture on reserves, and did indeed promise assistance with agriculture in the Numbered Treaties, in practice the support did not come through. Sarah Carter (1993), in her book Lost Harvests, concludes:

First Nations also found that their attempts to adopt agriculture were thwarted. While officially the federal government promoted agriculture on reserves, and did indeed promise assistance with agriculture in the Numbered Treaties, in practice the support did not come through. Sarah Carter (1993), in her book Lost Harvests, concludes:

“That the Indians might become agriculturalists provided justification for limiting the Indians’ land base and isolating them on reserves. Once these goals were accomplished, the Indians were largely left on their own.” (Ch. 1).

“But from the beginning it was the Indians that showed the greater willingness and inclination to farm and the government that displayed little serious intent to see agricultural established on the reserves.”(Ch. 2).

Here are various ways in which the Canadian government failed Indigenous agriculture:

- The government gave First Nations low-quality land. “The reserves associated with the numbered treaties may not be all rock and sand and muskeg…but on the Prairies they are often nowhere near prime agricultural land and they are usually bereft of other resources…” [7]

- Government incompetence or indifference. No assistance was available until the reserve was surveyed and agriculture had begun. The limited amount of assistance promised did not always arrive, or arrived too late to be useful for that season. The tools and animals provided were often inferior in quality. At first, equipment and seed arrived that was unsuited to western agriculture.

- Government interference. Until 1882, the government discouraged the use of machinery on reserves. Most reserves did not own a mill for grinding wheat, but off-reserve millers were notorious for taking a large cut of the flour they produced from clients’ wheat. Blacksmith services could be difficult to access. From 1881 on, the Indian Agent had the right to control all sales, bartering, exchanging or gifting of agricultural produce and other goods belonging to Treaty Indians or Indian bands.

- Corruption. The farm instructors sent out between 1878 and 1882 were often political appointees with no experience of Indigenous culture or Prairie farming. They had little means to visit reserves, which were often distant.

- Lack of credit. The government failed to extend credit to reserves. Private credit was usually not available due to the fact that creditors cannot seize Indigenous lands if borrowers default on loans.

- Government protection of White agriculture. From 1889 the Indian Act included a provision making it illegal for western reserve communities to sell agricultural products to non-reserve communities without special permission of the Indian agent. This provision was not removed from the Indian Act until 2014.

“An Indian girl more or less didn’t matter; and I’ve seen rations held back six months till girls of thirteen were handed across as wives to that…brute.”[8]

The Indian Agent role persisted until the early 1970s. Leroy Paul Wolf Collar writes:

“An Elder in my community told me that their hard-earned incomes generated from their farmlands and ranching businesses were often pocketed by the Indian Agent. Many reserve lands were sold by Indian agents without the approval of the Chief and Council, and in some cases without their knowledge.”[9]

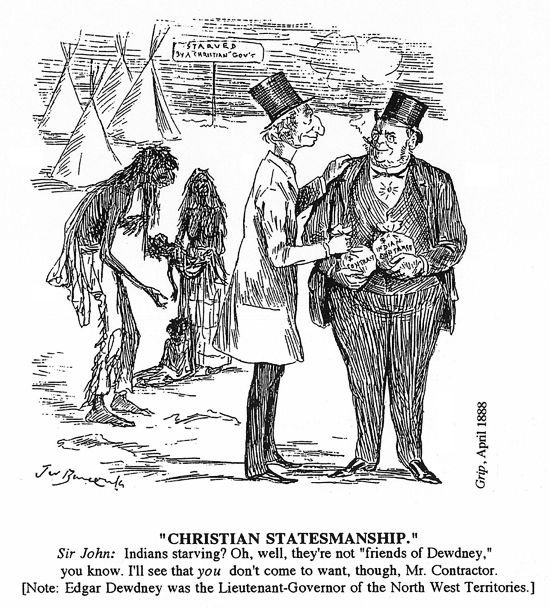

Back in the 1880s, when the government provided rations of flour, tea, and pork to hungry people in return for work, these rations were often moldy or rotting, unfit to eat. It was determined that rations suppliers were behaving corruptly, but none was ever prosecuted. Daschuck (2013) writes:

“Management of the increasingly serious food situation and Indian Affairs generally shifted from a position of “relative ignorance” under the Liberals to one of outright malevolence during the Macdonald regime [1878+]. The Conservatives, with Prime Minister John A Macdonald himself becoming superintendent of Indian Affairs, moved very slowly to provide food relief, waiting until the brink of starvation to lower government expenditures, and withholding food until bands not yet signatories to treaties signed on.”

Compounding the inadequacy of rations and reserve agriculture, the disappearance of the bison, and overfishing of lakes and rivers, a series of natural disasters gripped the region during the 1870s and 1880s. This included an extensive wildfire (1877), locusts, a series of droughts (1887-1896), and even a volcanic eruption in Indonesia (1883) which affected the global climate for several years. The situation on the Plains was desperate and potentially explosive. Daschuk continues (2013):

Things appeared quiet on reserves at the beginning of 1885, but tension seethed beneath the surface. Just days before the outbreak of violence in the spring of 1885, the Saskatchewan Herald castigated the government for its misguided ration policy and its role in making the indigenous population sick: “Everyone here knows that almost all of the Indians in the districts suffer from [tuberculosis] and dyspepsia… Their policy seems to be comprised in these six words: feed one day, starve the next.”

Little wonder that a series of killings erupted in 1885. The perpetrators were quickly hunted down and executed. Poundmaker and Big Bear, Cree Chiefs, were imprisoned because of rogue band members who had taken part in the violence.

These killings took place while a somewhat separate conflict, the 1885 Northwest Resistance, or “Northwest Rebellion” as it was formerly known, was underway. Once again Louis Riel was leading the movement. Riel called on First Nations to rise up and join him, and some did.

The Métis near Saskatoon, Saskatchewan had been re-living the dispossession they had experienced in the Red River Valley. Once again there was a standoff, an occupation, and a provisional government. But this time most Métis did not engage, nor did most First Nations. After three battles, in which at least 30 men including 10 Métis died, the conflict ended, resulting in the creation of a new province, Saskatchewan. The federal government took a much harder line with the instigators than it had in 1869. Louis Riel and eight Indigenous leaders were hanged. Another serious consequence was the institution of the pass system forbidding First Nations from leaving their reserves without permission.

To most non-Indigenous Canadians, all Métis were now rebels, which added to the discrimination they faced as non-whites. Redbird (1980; p. 25) writes: “The Métis movement disintegrated after the hanging of Louis Riel. The people subsided into their private lives as settlers began to pour into the west. The Métis lands were re-surveyed and the “carpetbaggers” juggled land claims and in general swindled the Métis out of what little they had left. Some adapted and a few adept Métis even prospered; some slipped into the white mainstream and others fled south to the United States…and some journeyed north “where you can live and die and never see a white man”.

After their disinheritance from early Manitoba and now Saskatchewan, many Métis were taking up residence on marginal lands such as road allowances. But they persevered, keeping their culture alive and pursuing land claims. The first Métis-specific advocacy group, L’Union Métisse St. Joseph, got started in 1887.

Much later, 1938, Alberta created 12 Métis settlements, 8 of which persist today. These are Buffalo Lake, East Prairie, Elizabeth, Fishing Lake, Gift Lake, Kikino, Paddle Prairie, and Peavine. These are similar to reserves. Until 1990 there was not much self-government on these settlements.

The situation was worse in Saskatchewan, where Métis were neglected, except for an ugly episode when they were forcibly relocated to farms run by government managers.

Though the federal government had maintained that Métis are not a federal responsibility, the Supreme Court (Daniels vs. Canada, 2016) has settled the debate in the affirmative. Métis are Indigenous people and the federal government has the same fiduciary responsibility towards them as it has to all who are “Indians” in the sense of the 1763 Royal Proclamation and the constitution acts of 1867 and 1982.

It is in some ways a blessing for the Métis that they were ignored by the federal government after 1885. Our next chapter describes various indignities experienced by the First Nations who survived the terrible 1870s and 1880s only to be trapped in poverty on reserves for generations. Even First Nations communities in eastern Canada who had long lived independently were turned into reserves and made to submit to Indian Act regulations. For example, the Kanien’kehá:ka who had come to Canada as Loyalists and who had been awarded lands in southern Ontario almost 100 years before Confederation became vassals of the Department of Indian Affairs, under the thumb of an Indian Agent until around 1970. Their traditional political structure, where clan mothers choose chiefs to lead the community[10], was outlawed.

The Oneida community of The Thames, which had come to what is now Ontario from the United States after purchasing land with permission of the local government, was also turned into a reserve under Indian Act management.

As First Nations languished in reserves, the economic and cultural divide between them and Whites became more extreme, reinforcing the notions of White superiority which had undergirded the Numbered Treaty process.[11].

- From Sea to Sea ↵

- Coates (2015) ↵

- Wolf Collar (2020), p. 9 ↵

- Wolf Collar (2020), p. 10 ↵

- Galea (2021) ↵

- BCSC (2021), Yahey v. British Columbia ↵

- Courchene (2018), p. 236 ↵

- Testimony against a sub-agent for the Department of Indian Affairs, recorded in Daschuk (2013), Chapter 8 ↵

- Wolf Collar (2020) p. 83 ↵

- Non-Indigenous Canadian women were not allowed to vote until 1918. First Nations men and women were not allowed to vote until 1960 ↵

- This vicious cycle was noted by Queen's student Marcus Davis in 2021 ↵

The Royal Proclamation of King George III, made in 1763, declared all lands west of the Appalachian mountains the domain of Indigenous people and specified that any settler wanting to acquire this land should do so from the Crown once the Crown made a treaty with Indigenous people to acquire rights to the land. For details, see Chapter 6.

After the Indian Act of 1876 was imposed, each reserve was overseen by an Indian Agent acting for the federal government. This lasted almost a century, ending in the early 1970s.

The Northwest Resistance, formerly known as the Northwest Rebellion, occurred in present-day Saskatchewan in 1885. For details, see Chapter 9.