The Modern Treaty Era

Let’s discuss the special challenges faced by small and remote communities.

Why don’t they just leave?

We often hear people say, or read in letters to the Editor, that the economic development of small, remote communities is hopeless, and the government shouldn’t encourage anyone to stay in these hopeless places. Why don’t people struggling with poverty in remote communities just leave? One in five Canadians was born in another country, and many more can recall an ancestor who left an economically poor situation to make a new life where opportunities were better.

Many people from small and remote communities do move. That is why, in 2021, 59% of Status persons lived off reserve. But do we really want northern Canada depopulated? Canada is culturally richer and geopolitically stronger when our lands are occupied. This way, diverse knowledge bases and specialist skills are available to scientists and innovators. For example, Inuit perspectives are informing studies of Climate Change in the Arctic.

Sometimes people who want to leave lack the resources to do so. They often cannot sell their existing homes or property for a price that would pay for a city home. They may lack the education or skills needed to get a decent job in the city. They might also be apprehensive about the faster pace of life and conversation in the city; the differences in body language and manners; and the possibility of discrimination.

For those who want to migrate, it would be good to have welcome centres in cities to help them establish themselves and to help them negotiate what can seem like a foreign culture. Newcomers may also need protection from scams and pimps.

Regarding those who want to stay, it does seem a bit rich to ask them to move when in some cases the government forced them onto their current lands and for many decades strongly discouraged them from leaving. And the fact that many remote communities are poor is in part the consequence of Canada failing to honour its treaty commitments.

Canada is a free country, and some people will always choose home, however remote. Let us consider the challenges faced in small and remote communities and how to overcome these challenges.

Economic Inefficiencies in Small and Remote Communities

Small and remote communities face challenges that larger communities do not face. Remoteness compounds the difficulty of being small. If you are small, but near enough to another community, many of your size-related problems will be mitigated. What is relevant is not your size but the size of the pool of expertise, service providers, agencies, politically active citizens, and markets that are near enough to access easily and affordably.

In terms of governance, we learned that smaller communities likely have fewer checks and balances in place to constrain local government. They are more likely to have problems of favouritism and political polarization. They are less likely to have expert advice at hand.

In terms of markets, small and remote communities miss out on internal economies of scale. If the community were larger, with more customers, or if the community could cheaply export its products, then businesses could have larger production runs, and achieve lower costs. This is because a firm’s average costs usually fall (for a time) as more output is produced.

Larger production runs allow a firm to spread its fixed costs – such as rent and advertising – over more units sold. Internal economies of scale are also relevant to the local government. Small governments must build similar-sized airports, health clinics, or police stations, whether there are 25, 250 or 1,000 residents. The larger the population, the more the tax revenues or fees that can be collected to pay for public goods, and the larger the subsidies that might be given by the federal government for public goods.

Another kind of economics of scale, called external economies of scale, refers to the advantage of having similar firms cluster together. The larger the community, the more likely it will be that there are multiple gas stations, multiple construction firms, multiple theatre groups etc. When there is an industry, rather than just one firm, in a particular business, the firms in the industry will be more efficient.

In terms of markets, remote communities face the disadvantages of high transportation and communication cost. Remote businesses pay more for inputs, which increases the cost of production. Remote businesses must pay more to ship to customers, reducing price competitiveness. One way to cope with this is to export small, high value-to-weight items such as artworks.

The difficulty of bringing goods to the Arctic is documented in a 2020 TV series called High Arctic Haulers.

Despite centuries of effort to find “the Northwest Passage” from Europe to India, Turtle Island’s northern coastal waters were not passable until 2007. Shipping should become easier as the Arctic Ocean warms.

The smaller the community, the greater the proportion of its goods that must be imported. When a community imports most of its goods, it is vulnerable to disruptions in supply or spikes in price.

The fact that so much is being imported means that money quickly leaks out of the community. No sooner is cash acquired for spending then it is committed to food, clothing, equipment, and vehicles manufactured in the south. That’s why Indigenous economies have been described as “bungee economies”.[1] The local spending multiplier weakens as money leaves the community.

In terms of productivity, small communities lack specialists. First, the smaller the group, the less likely it will have someone with a particular aptitude. Next, that person may have to leave the community to obtain training and might lose interest in returning. Finally, the small community likely cannot provide as much work for the specialist, or as high a salary, as a larger community.

Rather than fully specializing, the Inuit and northern First Nations and Métis have maintained mixed economies. On the one hand, individuals earn cash wages, receive subsidies, and possibly pay taxes. On the other hand, they continue to hunt, fish, gather, and manufacture traditional items which are shared locally or, in the case of handicrafts, sold to the south. Among the Inuit in 2016, 56% reported hunting, fishing or trapping, 42% gathering wild plants, 27% making clothing or footwear, and 18% making carvings, drawings or jewelry.[2]

Traditional activities are practiced for many reasons. Traditional activities are valued for keeping people connected to their past and for passing on knowledge, skills, beliefs, and a sense of identity. They keep people connected to one another, for example as they participate in hunts together and as they share the meat with elders and others.

Traditional activities also serve as a kind of insurance, keeping the food portfolio diversified. Typically, cash income is used to pay for traditional activities. The federal government contributes harvesting subsidies to promote traditional activities.

Traditional activities usually do not provide enough cash income to maintain a modern lifestyle, especially when traditional activities have to be balanced with the requirements of children’s schooling, and when they are challenged by habitat loss, competition from non-Indigenous hunters, and climate change.

Mitigating Smallness and Remoteness

To counter the economic disadvantages of smallness and remoteness, consider three Cs: connectivity, cooperatives, and currencies.

Connectivity:

Connectivity literally bridges the distance. Communities are connected by by bridges, roads, and airports; by the availability of intercity buses, trains, and flights; by telephone and internet access and speed; and by radio and television transmissions. Connectivity brings people together – specialists, customers, industry partners, inspectors, educators, journalists, politicians and more.

Investment in roads, railways, and waterways is important. There used to be a passenger train from Toronto to the tip of James Bay. As of 2020 it only runs the last third of that distance. Boarded-up hotels in Moosonee attest to the former era.

After Omnitrax abandoned its railway line and port at Churchill, Manitoba in 2016, First Nations, municipalities, a financier, and an Agrifood company joined forces to purchase and repair the railway. As of July 2019, the railway is being used again; its first cargo was brought to a ship proceeding from Quebec to Nunavut.

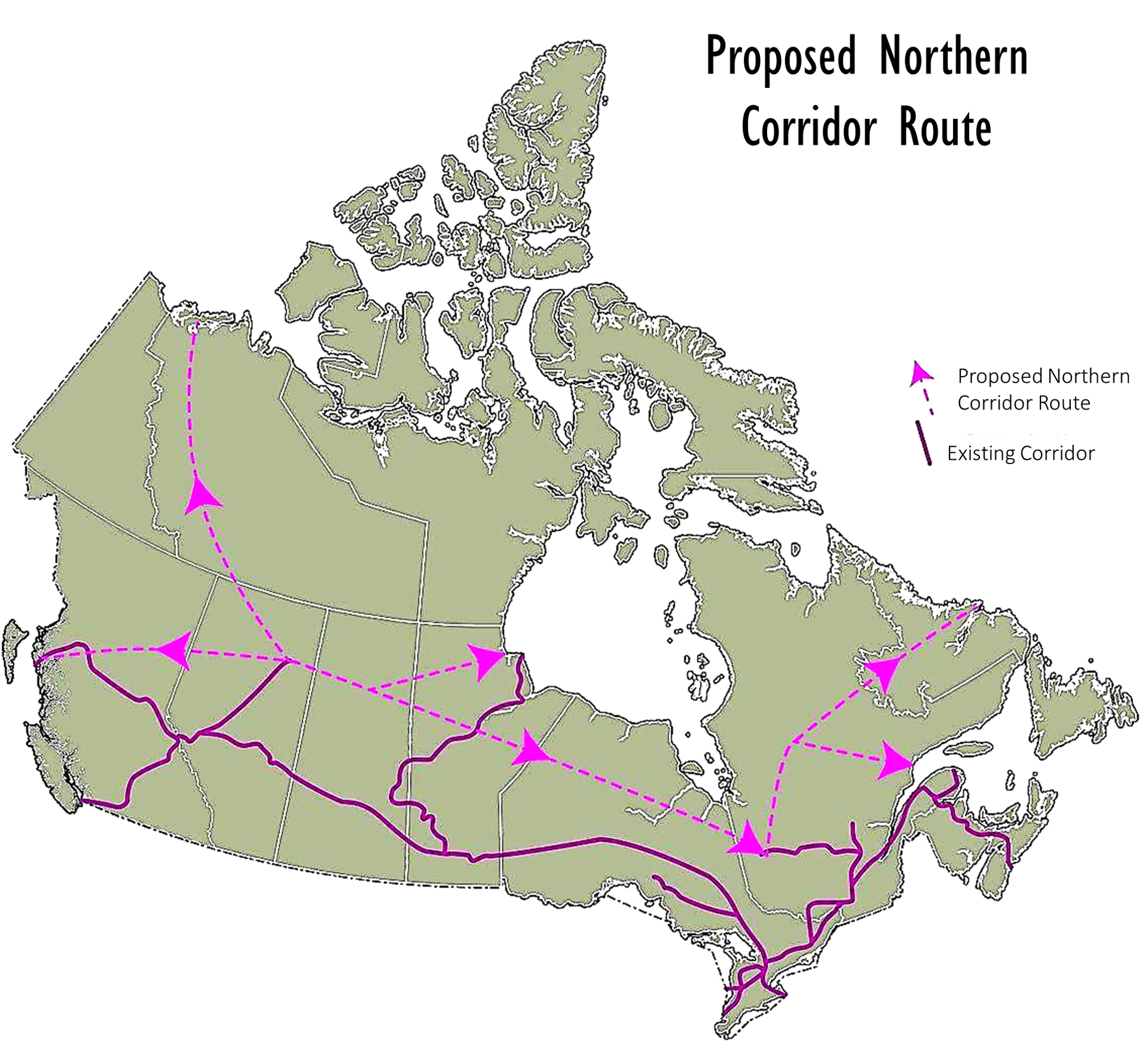

Recently, Sulzenko and Fellows (2016) have proposed the Northern Corridor Concept. Like Highway 401, this would be a route across Canada, but it would lie further north, with links to the Mackenzie Valley (North West Territories), Hudson Bay, and Labrador. It would include not only roads but railways, pipelines, electrical transmission lines, and communications towers. The authors understand the need for consultation with Indigenous communities. They believe that Indigenous communities would contribute to and benefit from the project.

The 2022 National Indigenous Economic Strategy calls for transportation and distribution routes that benefit Indigenous communities (NIEDB et al., p. 38).

Internet connectivity is increasingly important for everyday life; it has become essential for schooling, travel planning, health care, and business. However, as reported by the CRTC in 2016, remote communities often lack the infrastructure to provide either fixed or mobile access to the internet. Other problems are affordability of plans and lack of familiarity with the technology. In 2015, only thirty percent of Nunavut households had at least 5 Mbps (megabytes per second) download speed, and none met the government’s target of 50 Mbsp. First Nations communities were among the most disadvantaged communities in terms of internet connectivity. (CRTC (2016)).

Federal, provincial, and territorial governments have pledged funding to expand broadband coverage in rural, northern, and First Nations communities. For example, in 2021, the province of Manitoba contracted with Xplornet Communications to provide service to 380 rural communities including 30 First Nations. In 2022, the federal government announced an additional $1 billion for broadband coverage; the First Nation Infrastructure Fund will provide additional funding specifically for First Nations.

First Nations themselves are taking steps to improve internet connectivity. First Nations-owned K-NET Services (Northern Ontario, Quebec and Manitoba), the First Nations Education Council (Northern Quebec), Mamawapowin Technology Society (Samson Cree First Nation), and the Cree Nation Government in conjunction with local municipalities (Northern Quebec), have each used various means such as acquiring satellites, laying down fibre-optic cable, building cell phone networks, or installing public wi-fi hotspots.

Investment in internet connectivity is important to ease the “banking deserts” that often exist in the north. A community may be a hundred kilometres away from the nearest bricks-and-mortar commercial bank or credit union; furthermore, residents may be unable to afford a laptop, may be without good internet service, or may find online banking technically complex. They may be more comfortable with in-person interaction, which is in fact often required when asking for loans.

The absence of commercial banks means that some communities rely too much on cheque cashers, payday lenders, and pawnbrokers. One idea to improve banking access in the North is to equip local Post Offices to offer financial services.

To improve connectivity, communities can consider relocating closer to markets. They might be able to purchase additional lands closer to cities. This will improve access to jobs and educational opportunities. However, if part of the community refuses to move, this remnant will be left in an even worse economic position than before.

Cooperatives:

Cooperatives are locally-managed, member-owned businesses, either for-profit or not-for-profit. During the late 1960s, socially-minded organizations from southern Canada such as the FCNQ – Fédération des Coopératives du Nouveau-Quebec – initiated, supported, and financed cooperatives across the Arctic. These have been very successful, becoming integral features of Inuit communities.

“…Cooperatives were readily acceptable because they could be seen as extensions of the informal cooperative activities necessary for survival in the Arctic – the collaborative hunting of seals and other animals, much of the fishing that Indigenous people undertook, and the familial gathering of other foods. Living a lonely, isolated, individualistic life is not a common alternative in the Canadian Arctic.” (Southcott, 2015)[3]

In Canada’s north, cooperatives operate stores, hotels, rental properties, waste-water systems, drinking water systems, and greenhouses; they are involved in construction, outfitting, providing cable television services, and selling arts and crafts to the south.

In Canada’s north, cooperatives operate stores, hotels, rental properties, waste-water systems, drinking water systems, and greenhouses; they are involved in construction, outfitting, providing cable television services, and selling arts and crafts to the south.

One cooperative is West Baffin Eskimo Co-operative Limited (westbaffin.com) in the town of Kinngait, Nunavut (population 1,396 (2021)). According to its website, most of the community’s adults belong to this cooperative and thus share in its profits. According to Brown (2022), the co-op runs the community’s general store, a fuel delivery business, a snowmobile & ATV repair shop, and Kinngait Studios, one of the most famous sources of Inuit art. At the studio, the co-op pays each artist for their artworks, and then sends the works to Dorset Fine Arts in Toronto. Dorset Fine Arts sells the art to museums and galleries.

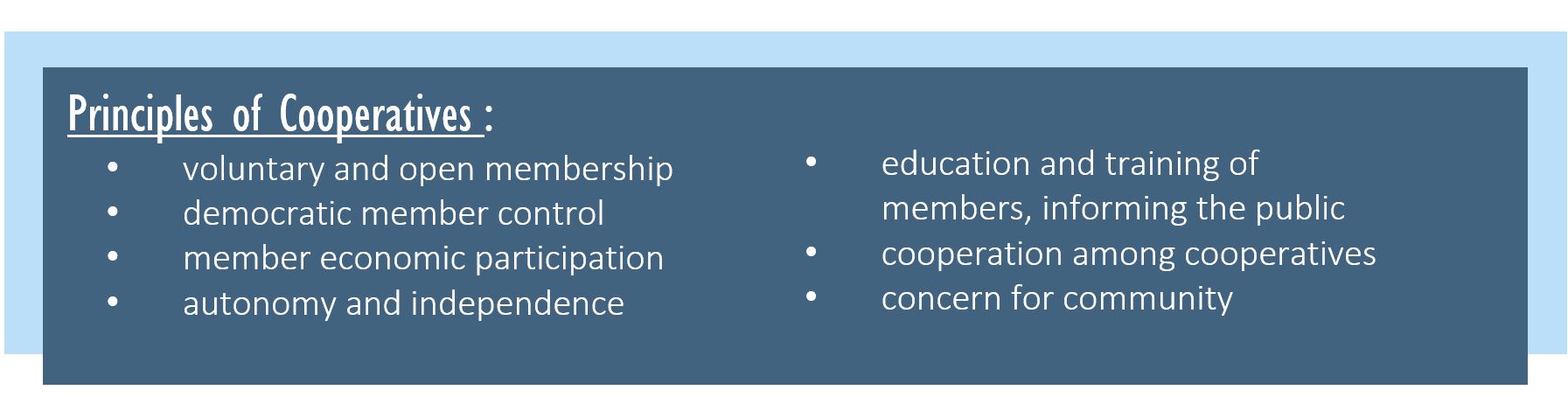

Normally, economists expect privately-run businesses to outperform and eliminate co-operatives, but the table below reveals that there can be advantages to cooperatives which might be especially relevant in the North.

Co-operatives, in contrast to privately owned businesses, are more likely to:

- Reflect local needs and desires

- Respond quickly to local needs and desires

- Invest profits locally

- Remain in the community, providing stability

- Train and employ locals

- Understand local employees’ time constraints e.g. hunting schedules, funeral obligations

- Hire women[4]

- Nurture leaders.

In the year 2000, half of the members of the Nunavut Legislative Assembly had experience managing cooperatives.[5]

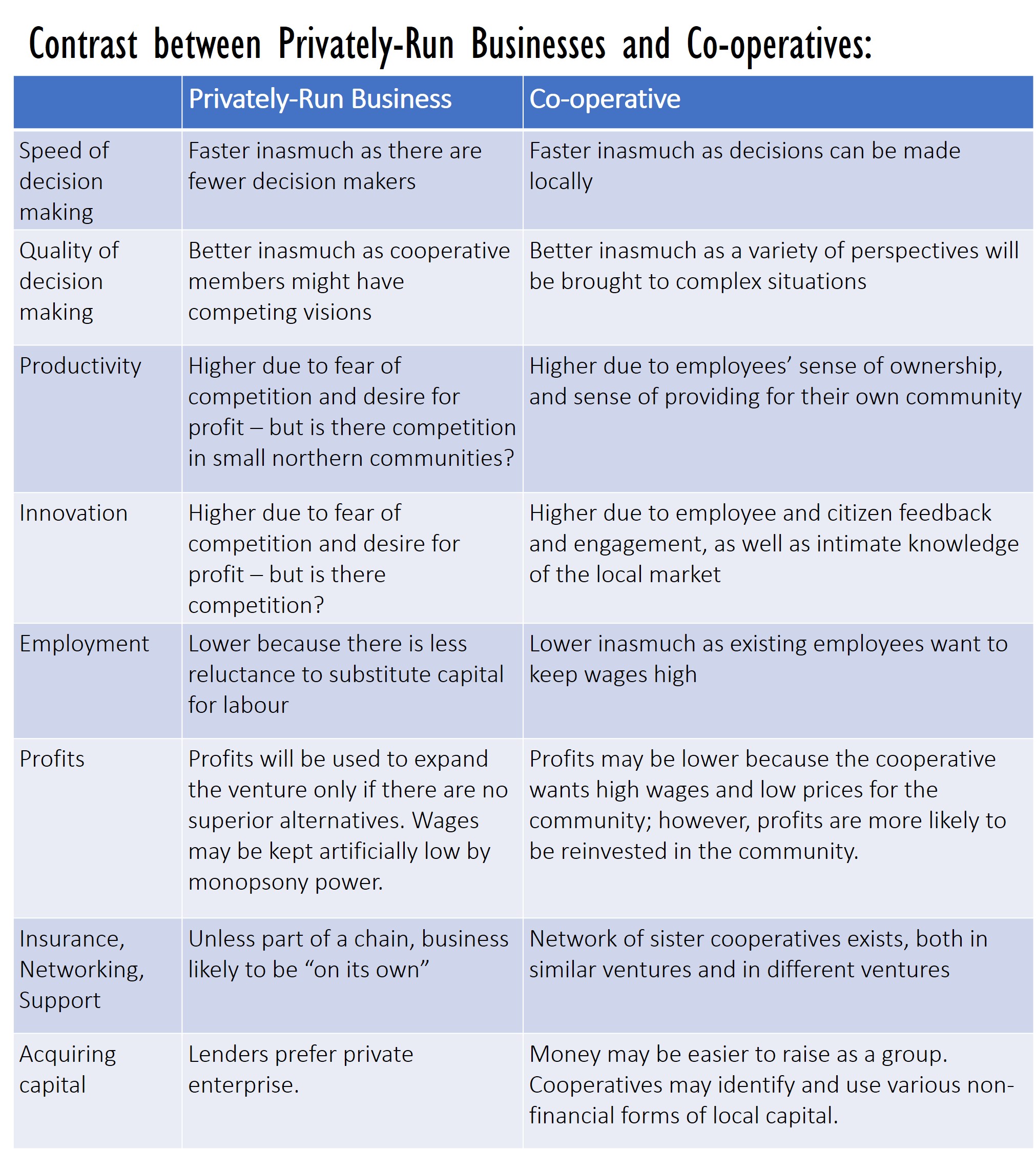

The following table compares co-operatives to privately-run businesses. The first entry, speed of decision-making, tells us that privately-run businesses may make decisions faster than cooperatives, or vice-versa, depending on circumstances.

Capital and cooperatives

In Canada’s north, cooperatives are an important form of social capital. Volunteerism, traditions around knowledge sharing, informal childcare and elder care arrangements, and family cohesion are also sources of social wealth or social capital.

We use the word “capital’ in the economic sense, to describe something that provides a flow of services not just once but year after year. Cooperatives can be considered part of a community’s social capital if they strengthen social bonds and provide for community needs on an ongoing basis.

Cooperatives can also provide financial capital. Loans may be scarce in the north because of the lack of traditional banking services and because community members have low credit scores. Members of a local cooperative have personal knowledge of many community members and may be willing to offer credit.

Because members of a cooperative are local, they have an edge in identifying the assets of their community and capitalizing them – putting them to work to generate revenue.

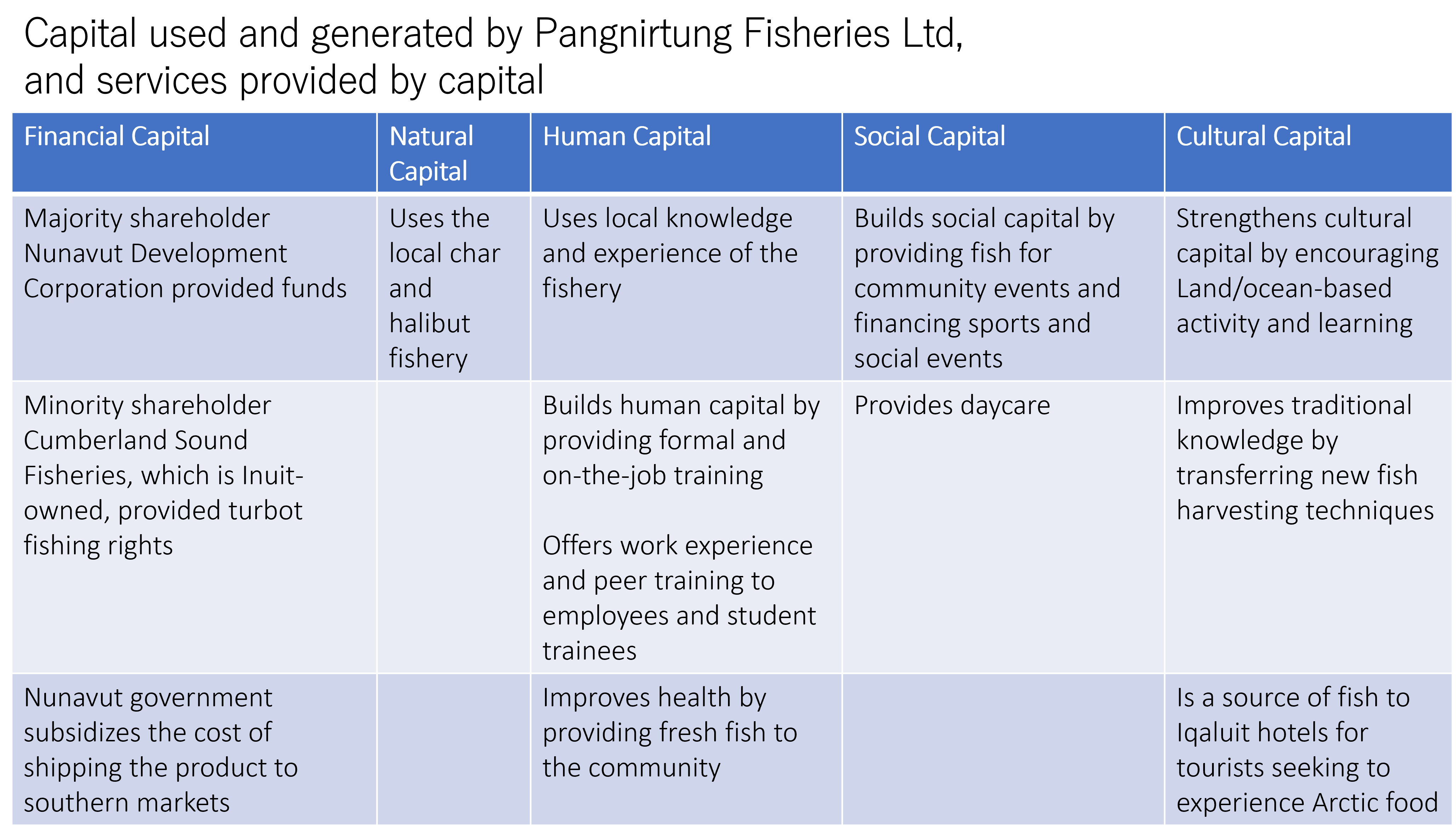

The Capital Assets Model was created by development theorists like Carole Rakodi (1999) to identify a community’s assets. Thierry Rodin (2015) used this approach to describe how Pangnirtung Fisheries Ltd, a community-owned and operated business, uses and develops Pangnirtung capital:

Local Currencies:

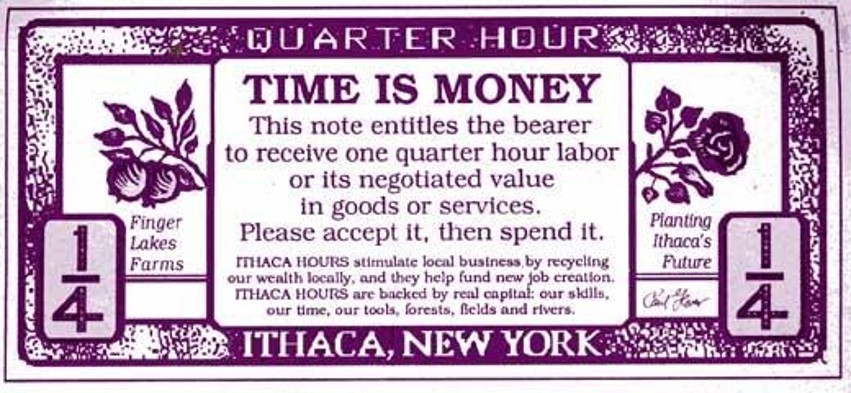

A local currency is paper or electronic money that is created locally to be used locally. The currency is only valid in the community where it is issued. Since it can’t be spent elsewhere, anyone owning this money will need to shop locally.

Local currencies offer three possible advantages over official currency. They promote local spending, they allow for local influence over the money supply, and they in theory could give an exchange rate advantage.

The exchange rate advantage would be due to the local currency being less valuable than the official currency, making goods priced in this currency more affordable to outsiders. However, any such exchange rate saving for the outsider is probably countered by the hassle of an outsider having to obtain the specialized local currency in order to make a purchase. Hence communities with local currencies never insist on being paid in the local currency.

The impact of a local currency on a community’s money supply is more relevant. The supply of local currency could be increased to combat local recessions and decreased during booms. The greater the extent to which the local currency was being used, the greater the influence of its availability would be.

When people feel they don’t have enough official currency to make a purchase or hire labour, they may be too embarrassed or cautious to barter for what they want. Local currency can make the intended transaction possible.

But the main advantage of local currencies is that they promote local spending.

How local currencies promote local spending:

Local currency is spent locally. Because official currency is scarce, local currency serves as an additional source of spending that bounces back and forth in the community, generating a local spending multiplier effect.

How does the ball get rolling? Sometimes local currency is given away freely in the beginning. For example, babysitting cooperatives sometimes give members babysitting currency when they join the cooperative, worth say 20 hours of childcare. Members can spend the currency on childcare for their own children, and they can earn more currency by providing childcare to other members’ children. Upon leaving the cooperative, members must refund the babysitting currency they initially received.

In Sardinia, an island belonging to Italy, the local currency is called Sardex. Sardex is completely electronic. A loan of Sardex is issued to firms having a large inventory of goods they are willing to sell in Sardex.

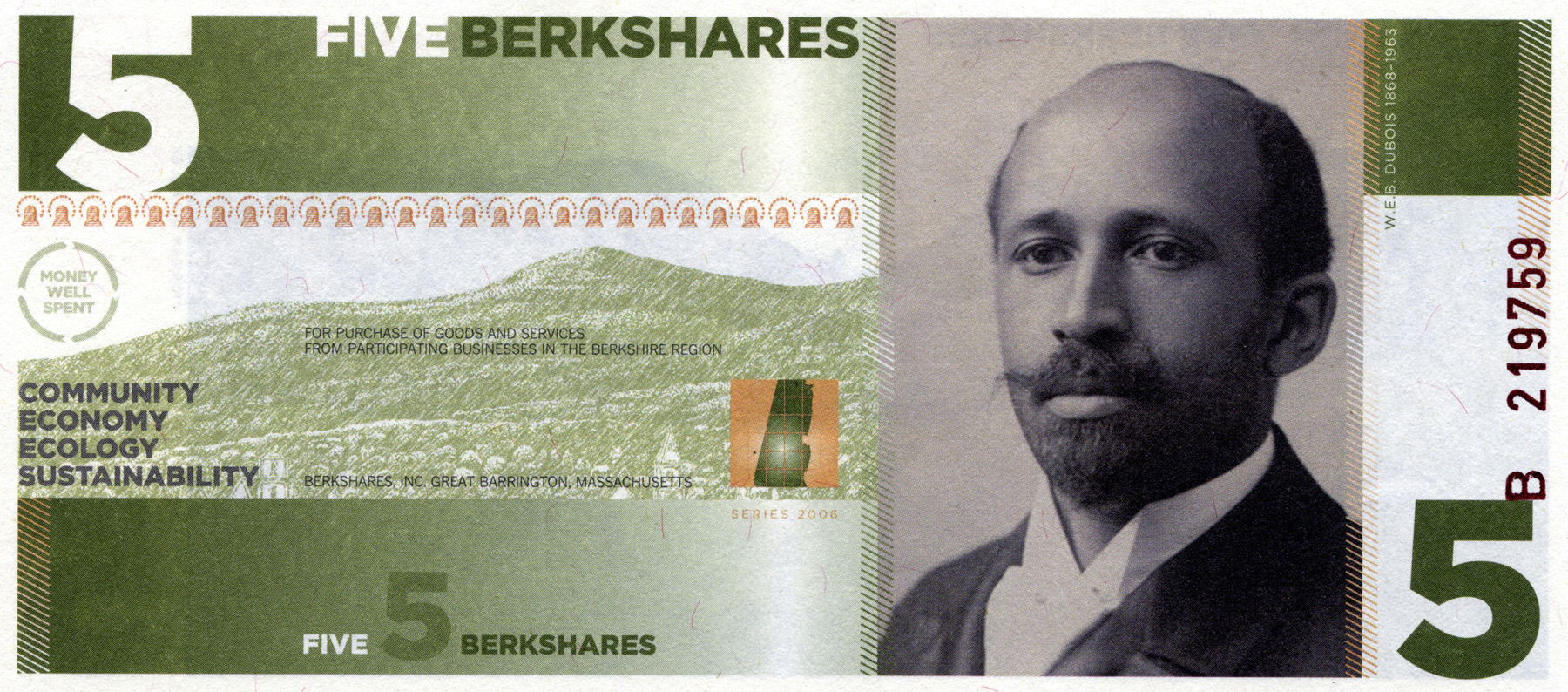

When the local currency can be purchased with official currency, it doesn’t cost as much as official currency. For example, I can buy one Berkshare=100 Berkshare cents for ninety-five US cents. Merchants in the Berkshires area of Massachusetts are willing to sell me one US dollar’s worth of goods for one Berkshare, implicitly giving me a 5% discount, because they want my business. And they understand that the more money that goes around (in the community), comes around (in the community).

When the local currency can be purchased with official currency, it doesn’t cost as much as official currency. For example, I can buy one Berkshare=100 Berkshare cents for ninety-five US cents. Merchants in the Berkshires area of Massachusetts are willing to sell me one US dollar’s worth of goods for one Berkshare, implicitly giving me a 5% discount, because they want my business. And they understand that the more money that goes around (in the community), comes around (in the community).

The risk that the Berkshare will go out of fashion or be rejected by vendors is covered by the fact that the American dollars that were used to buy the Berkshares are saved by the organization so that it can buy back any Berkshares that are no longer wanted. In the case of the Sardex, which is not purchased, there is the risk that the Sardex will no longer be accepted and you will be left with a balance of useless Sardex that exceeds the amount you were originally given.

You might be interested to know that a local currency can be subject to sales taxes mandated by a higher level of government.

In Massachusetts, the state sales tax is applied at the usual rate to the Berkshare-price. The vendor has to remit the tax collected, in USD.

If local currencies were a magic bullet for regional prosperity, we would surely see more of them. As it is, The Economist reports that local currencies struggle and that “of over 80 launched in America since 1991, only a handful survive.” (January 7, 2017). The Swiss WIR has survived since 1934.

Sardex co-founder Guiseppe Littera has advised that a local currency needs at least 600 member businesses, based on his experience in Sardinia.[6] This would appear to rule out success in a single northern community or on a singe reserve. Across a northern region there could be 600 locally-owned businesses, but would there be enough interaction among them, seeing as they would be very much spread out geographically?

So then, local currencies are an intriguing but unlikely option for Canada’s small and remote communities; cooperatives are tried and true; and improvements to connectivity are fundamentally important.

So then, local currencies are an intriguing but unlikely option for Canada’s small and remote communities; cooperatives are tried and true; and improvements to connectivity are fundamentally important.

Let’s now consider issues facing urban Indigenous communities.