Economies prior to the late 20th Century

It was the fur trade that most energized the colonization of Canada by Europeans, and it was beaver pelts that were most sought after. Even the beaver skins that had been worn for a year or two as clothing had their value, because it was not the long shiny outer hairs that were useful, but the softer, shorter inner hairs, which could be pressed into felt. For three hundred years (1550-1850) beaver felt hats were fashionable in Europe.

After Britain took control of French colonies, rivalry in the fur trade in what is now Eastern and Central Canada was no longer between colonial powers but between companies. Companies based in Montreal, and independent entrepreneurs, set out across the Great Lakes, and from Lake Winnipeg up the Saskatchewan River, ever westward in search of fur. Further north, the Hudson’s Bay Company held sway. Sadly, we must pause to remember that, as traders and European goods moved west and north, diseases such as smallpox, whooping cough, and influenza spread also. The low population density in the north would have reduced the impact of these diseases, but as Indigenous-European trading networks spread, stabilized, and involved more and more participants, diseases took a terrible toll.

Sadly, we must pause to remember that, as traders and European goods moved west and north, diseases such as smallpox, whooping cough, and influenza spread also. The low population density in the north would have reduced the impact of these diseases, but as Indigenous-European trading networks spread, stabilized, and involved more and more participants, diseases took a terrible toll.

We know that about 18% of the population around York Factory died in that region’s first smallpox epidemic, 1781-2.[1] In another incident, during the summer of 1858, Whooping Cough killed 30 out of fewer than 200 people at Moose Factory. Other crisis death years in the region were 1884, 1885, 1891, and 1898. Epidemics would exploit malnourished populations and would also contribute to malnutrition by weakening or killing hunters and knowledge-keepers.

The Influence of the Hudson’s Bay Company:

The Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) came to dominate the fur trade in present-day Canada because of Rupert’s Land, the vast expanse of territory it controlled. The British Crown had given the company a monopoly on commerce in Rupert’s Land.

Despite its official monopoly, the Hudson’s Bay Company could not ignore competition from voyageurs based in Montreal. Beginning in the 1770s, HBC felt it necessary to set up trading posts inland rather than solely on the shores of Hudson Bay and James Bay. The many deaths of Cree wholesale fur suppliers from smallpox in the 1780s gave even more reason for this strategy.[2] Later, HBC faced stiff competition from the North West Company (1779-1821), with which it eventually merged. HBC’s reach expanded beyond Rupert’s land, all the way to British Columbia by 1827.

In many ways, the dominance of HBC in Rupert’s Land was probably preferable to a more competitive fur-trading environment. The period of time when the North West Company was competing with HBC for furs in what are now Manitoba and Saskatchewan was difficult for the First Nations – who were bullied and plied with alcohol – and on the stock of fur-bearing animals.

By contrast, when monopoly conditions prevailed, HBC kept an eye on sustainability and discouraged traders from unscrupulous activity. It attempted to hold the behaviour of its employees to a high standard. It discouraged alcohol consumption. It vaccinated Indigenous communities. Eventually it required its employees to pay insurance that would support Indigenous wives, girlfriends and children who might be abandoned when those employees returned to England.

On the other hand, HBC used its monopoly power to keep fur prices favourably low for itself. We see this in the fact that Indigenous suppliers were paid for fur, or for their service to the post[3], with credit. The amount of credit was measured in “made beaver”, the value of a prime beaver pelt. Because they were paid in credit, Indigenous suppliers were forced to use their earnings to acquire goods at the post to which they sold their furs. And they were forced to sell fur to the posts where they wished to buy goods. If they had been paid in cash, they could have shopped around for better prices. Not until the late nineteenth century, when the railroad was bringing rival traders much nearer, did HBC pay Indigenous people in cash.

The fur trade’s initial boost to First Nations’ standard of living:

Ann Carlos and Frank Lewis (2010) have scrutinized the fur trade of the 1700s at the HBC post called York Factory, which is at the mouth of the Nelson River on Hudson Bay. Here HBC was collecting furs from Assiniboine, Cree, Chipewyan and other native suppliers.

Carlos and Lewis believe that the material standard of living of the local First Nations at this time would have been higher than before contact with Europeans, because of the new goods they now could acquire in exchange for fur: guns, ammunition, nets, sewing needles, knives, kettles, and pots. What do most of these objects have in common?

Using HBC records and diaries, Carlos and Lewis demonstrate that:

- Local hunters were strong bargainers and choosy consumers, and HBC took pains to anticipate and respond to their shopping preferences.

- By 1770, local hunters who traded at the York Factory post were spending 34% of their earnings on guns, tools, nets, and other producer goods; 7% on household goods, 13% on alcohol, 20% on tobacco, and 27% on non-alcohol and non-tobacco luxury goods such as tea and jewelry. They purchased no food at all. What does that suggest to you?

-

Local hunters were interested in raising their incomes. They responded to higher fur prices by supplying more fur.

-

Local hunters and their families enjoyed a good standard of living. Their diet, which was diverse and protein-rich, was better than the diet of most people living in England at the time. Their clothing was at least as valuable as the average English wardrobe. Their housing, however, consisted of necessarily temporary structures which were much less comfortable than the housing of even low-wage English.

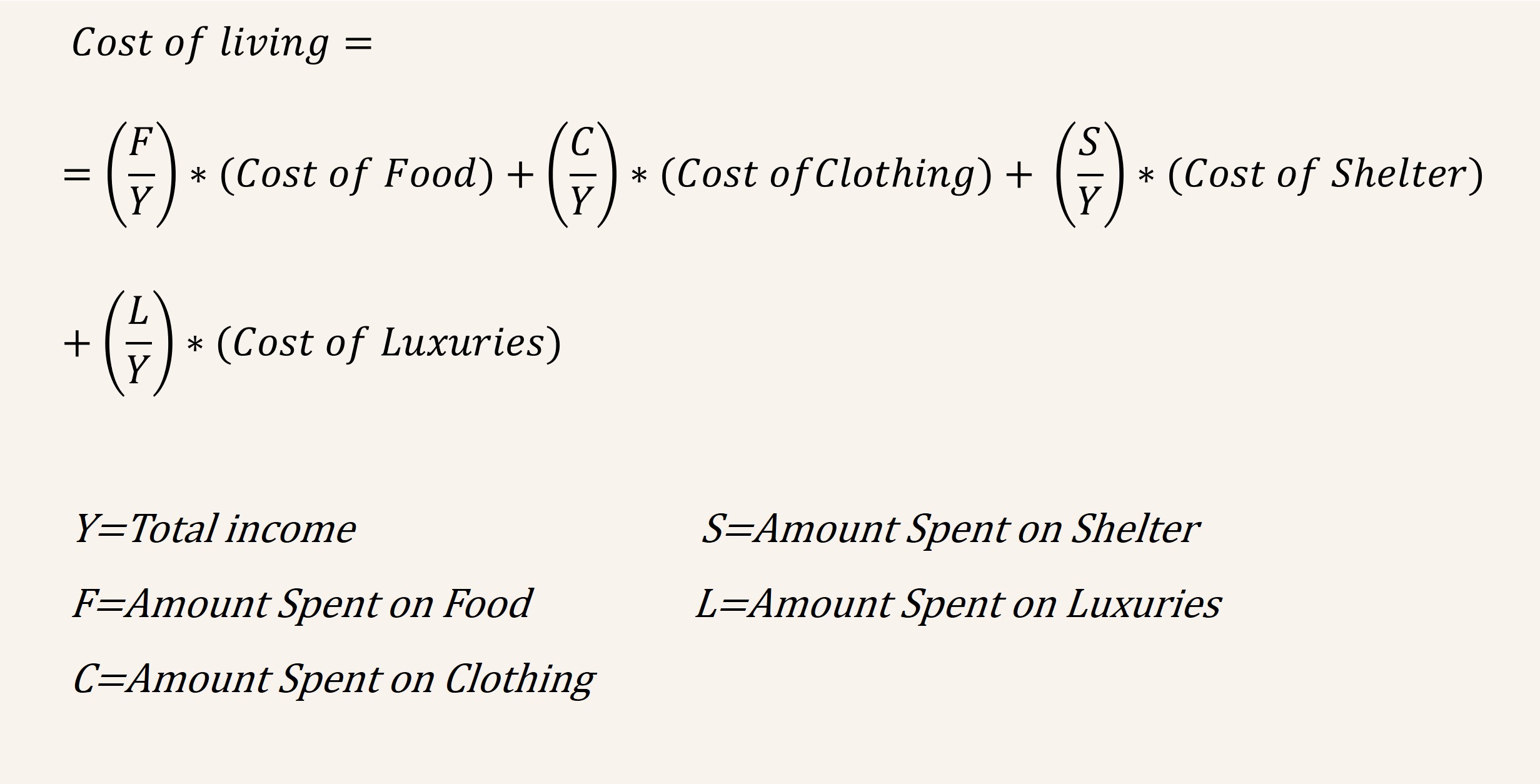

Overall, local hunters and their families consumed a package of goods that was similar in value to that of working class English families. How do Carlos and Lewis come to this conclusion?

Since First Nations did not purchase food at the posts in the 1700s, Carlos and Lewis determine how much meat was absolutely necessary for survival by First Nations given the other foods they could count on, such as fish, wild vegetables, fruits, berries, sap etc. This amount of meat, valued at English prices, would have been completely unaffordable to most people in England; and the English did demonstrate a preference for a meatier diet when they could afford it. The fresh, wild meat eaten by First Nations was a cut above much of the meat products – sausage, haggis, head cheese – consumed by poorer British households.

To value clothing, the authors ignore labour costs and focus on the number of moose hides needed for clothing and the number of deerskins needed for footwear over the course of a year. They then price these hides by how much they were worth in made beaver at York Factory.

In 1740, the year of comparison, beaver pelts were selling for at least 5 shillings in England, and Carlos and Lewis use this to estimate that an Indigenous family of five would have £13 worth of clothing compared to £1.2 for a low-wage worker’s family in England. I think you’ll agree, however, that it is questionable whether English people would have wanted to be dressed in leather. We could instead have asked how much it would cost for an Indigenous family to purchase the fabric worn by English families. This forces us to realize that people adjust to higher prices by choosing different goods to eat and to wear.

Meat is arguably better than potatoes, and leather than fabric, but each group was consuming the goods most readily available and inexpensive, and the ones to which they were accustomed. The foreign goods would necessarily have been more expensive, and not necessarily preferred.

Meat is arguably better than potatoes, and leather than fabric, but each group was consuming the goods most readily available and inexpensive, and the ones to which they were accustomed. The foreign goods would necessarily have been more expensive, and not necessarily preferred.

Carlos and Lewis decide to create a measure of the cost of living using those two points of view, namely, using the consumption preferences of each group. They impute the amount of food that First Nations hunted, since during the 1700s First Nations did not buy food at the post. They do not consider any food produced at home by Indigenous (or English) families. Not knowing spending details for the average family, they go with spending shares, which they can observe from trading post and British shopping records. So they are not comparing incomes, and what each group could afford to buy. They are comparing how much a typical consumption bundle would cost in two different countries and currencies. First they look at how much a native consumption bundle would cost in the Hudson Bay area or in England, and then they look at how much an English consumption bundle would cost in the Hudson Bay area or in England.

The Fur Trade and Economic Development:

As Carlos and Lewis said in the quotation above, biology limits the expansion of wild fur collection. For the fur trade to promote economic growth, it would have to have significant spin-offs into other industries.

The Staples Approach is a way of analyzing trade in commodities by evaluating the quality of those spin-offs. This approach was developed in the 1920s by Queen’s Professor W.A. Macintosh and University of Toronto Professor Harold Innis. The Staples Approach organizes Canadian economic history by the most important commodity collected from more remote areas to be sold to more industrialized areas. The Staples Approach analyzes the unique impact of each era’s staple commodity – fish, fur, lumber, wheat, minerals – on the economy of the time.

Each staple which is traded makes particular demands on inputs such as the various kinds of labour required and supporting industries. Each staple attracts and advances particular classes of people and institutions. It makes use of particular resources and skills. These are called backward linkages. Each staple also potentially allows for further processing of the staple and the development of industries that use it. The staple also provides local income which is spent in particular ways, stimulating other industries and activities. It develops new skills, and new goods and services. These are called forward linkages.

Note that hat-making did not take place on Turtle Island. France and Britain discouraged manufacturing in their colonies. Colonies were to be cultivated as sources of cheap raw materials and as markets for the goods manufactured in Europe.

Carleton University Professor Mel Watkins believes that First Nations were neither very much harmed nor helped by the fur trade. Not much harmed, because they were able to sell fur autonomously, individually, and independently; they were not much helped, because the fur was exported to foreign shores where most of the value of the final product was added. In his book Dene Nation: The Colony Within (1977)[4], Watkins writes:

“The Hudson’s Bay Company appropriated such enormous surpluses from the fur trade that it is now a major retailer, real estate developer, and shareholder in the oil and gas industry. Indeed, beyond that, the fortunes that originated in the fur trade went on to spawn yet greater fortunes in banking and railways. Of what benefit has this been to the northern aboriginal peoples who produced the fur?”

Beaver Depletion:

The fur trade put severe pressure on the stock of fur bearing animals, even in remote areas. Beaver in particular were almost completely exterminated from the Hudson Bay area several times: during 1733-1763[5], 1800[6], the early 1820’s[7], and the 1930s. Ray (1974) notes that although hunting and trapping were primarily responsible, beaver diseases, forest fires, and droughts at times aggravated the depletion of beaver.

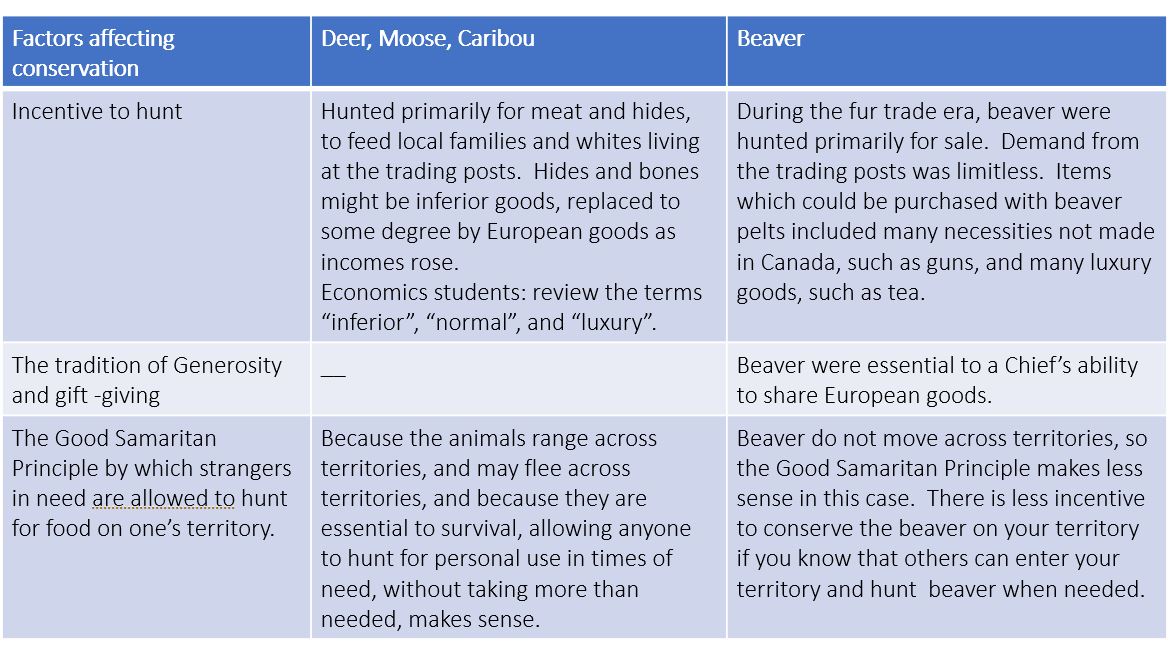

In an earlier chapter we discussed Indigenous values and hunting norms. How is it possible that Indigenous peoples who so respected nature, and who believed that taking more than is needed is offensive to animal spirits, could have hunted beaver to the point of extinction? Three explanations of overhunting come to mind.

One explanation is migration. The introduction of new trading opportunities, guns, new diseases, and European settlement triggered both voluntary migrations and intertribal conflicts which resulted in migrations. For example, some Cree moved west and north, while others moved southwest. Inuit moved south and Chipewyan moved southeast. Anishinaabe moved northwest. Even within tribes, families reorganized due to deaths, marriages, and the coming to adulthood of children. As territories changed, new sets of hunters had to learn the locations, habits, and stock size of the different animals on their territories. Migration would reduce hunters’ knowledge of the land and perhaps their feeling of being spiritually tied to it. Another explanation of overhunting is trespassing, stealthy or overt, by rival Indigenous groups or by white hunters.

There is also the profit motive, to which no human is entirely immune. Demand for fur was steady, so the pressure to hunt was relentless, despite the beaver population cycling in a natural rhythm. Carlos and Lewis (2010) argue that the traditions and norms around territorial ownership among the local hunters, norms like the Ethic of Generosity, and the Good Samaritan Principle discussed earlier, were useful in preserving game animals such as deer, moose and caribou, which are hunted for meat and which were essential to survival, but not sufficiently useful in protecting fur-bearing animals. The Table below shows the differential effect on deer and beaver of hunting norms and hunting incentives.

Beaver Conservation:

During the Great Depression of the 1930s, consumer spending crashed. Fur prices, like other prices, fell. Coincidentally, animal populations in the Hudson Bay region were very low. This was a time of great poverty for fur-hunters and trappers in Ontario and Quebec.

In response, James Watt of the Hudson’s Bay Company, other HBC representatives, Cree leaders, and the governments of Quebec and Canada devised a system of beaver reserves in Northern Quebec. Beaver conservation areas were assigned to specific Cree bands. Only the Cree themselves would be permitted to hunt and trap on these lands, while respecting a quota set by the government using data that the Cree themselves would report. Reserve guardians would be paid by the government to monitor beaver levels, and this money would help them pay their bills until the beaver stocks rebounded. Hunters and government officials would meet once a year to discuss stock management. The beaver populations recovered quickly, doubling every year from the initial stock of existing beavers or re-introduced beavers!

Today, the Cree of northern Quebec’s right to hunt beaver and other animals sustainably for fur and meat is protected by the 1975 James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement, an agreement which basically converted those beaver conservation areas to self-governed Cree lands. The James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement includes many self-governance provisions for the Cree, and also for local Inuit. This first Modern Treaty, and its principles of territorial rights and Nation-to-Nation cooperation, were foreshadowed by the earlier beaver conservation plan.

- Carlos and Lewis (2012) ↵

- Brown (2020) ↵

- Trading posts were served by “home Indians” who supplied the posts with meat and manual labour. ↵

- The following discussion is from the Preface of the book, published in Grant and Wolfe, eds. (2006) ↵

- Carlos and Lewis (2010), Chapter 6. ↵

- Carlos and Lewis (2010), Epilogue. ↵

- Ray (1974), Chapter 6. ↵

Backward linkages, or upstream linkages, refer to the impact of an economic activity on suppliers of inputs, workers, communities, and environments.

Forward linkages, or downstream linkages, refer to the usefulness of an economic activity in providing materials, skills, and services for new products and economic activities.