The Modern Treaty Era

Infrastructure is physical capital that provides services which are shared across the community. Infrastructure includes water filtration plants, sewage systems, electricity grids, cell phone towers, roads, and more.

Infrastructure goods are public goods: goods which can be shared without detriment to anyone. There is a classic “public goods problem” familiar to students of economics. The problem is called free riding. People try to ride free on public goods. They are not willing to pay their fair share and they tend to understate their willingness to pay. That is why public television stations and public radio stations ask viewers and listeners to contribute but end up relying on grants from governments and charitable foundations.

Because of the public goods problem, it’s up to government to make sure there is enough infrastructure in the community.

Prior to the 1970s, Indian Agents supervised much of what went on in reserves, and Band governments were not entrusted with much responsibility.

The blame for the inadequacy of infrastructure on reserves before the 1970s can be assigned to the federal government and the voters who elected each administration.

In the 1980s, Bands were given back some independence, including responsibility for infrastructure. But funding, as we learned in Chapter 17, stagnated for a thirty-five year period beginning in the early 1980s. Responsibility over infrastructure expanded faster than Bands’ capacity to afford and manage infrastructure.

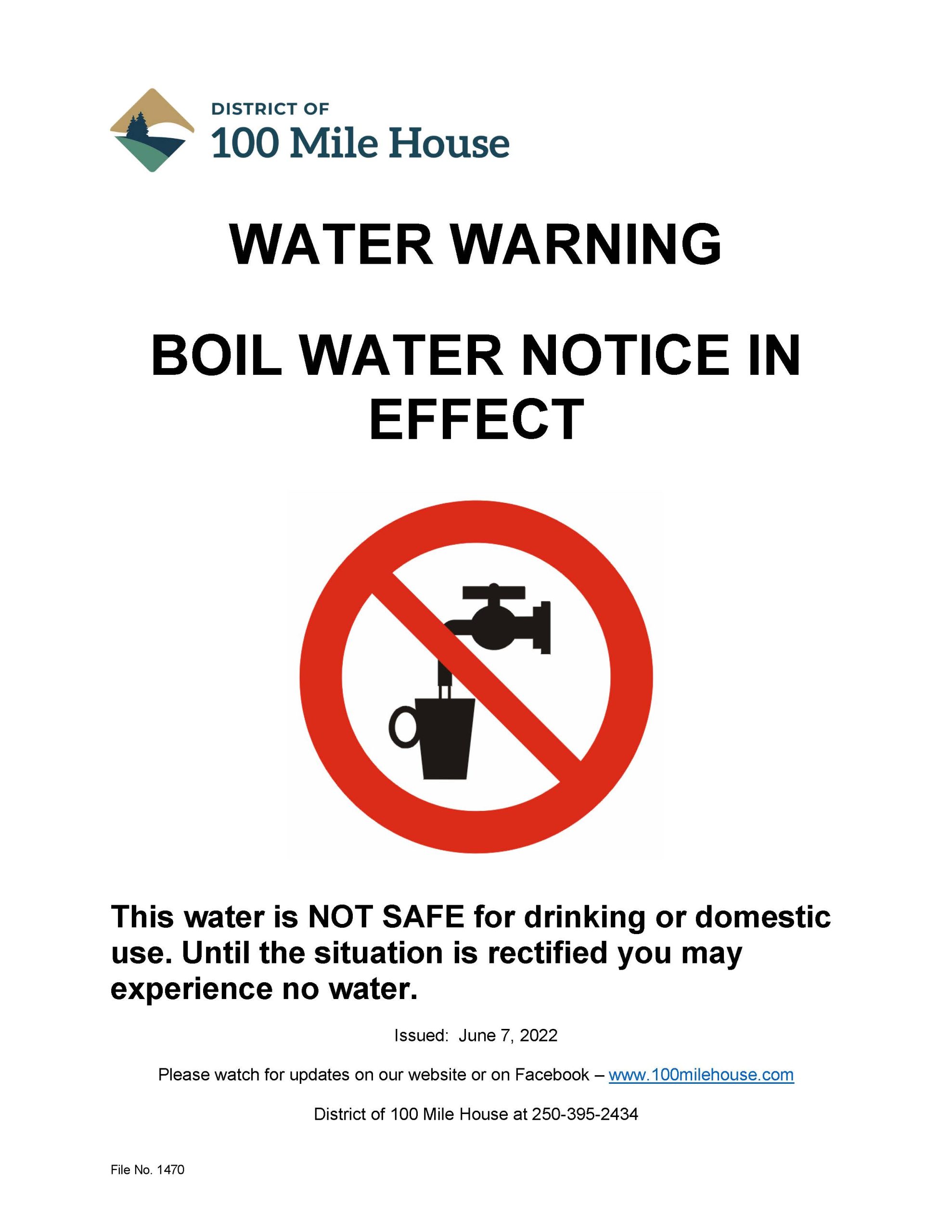

Infrastructure on reserves remains deficient, especially on northern reserves. An index compiled by the Centre for the Study of Living Standards shows the significantly lower levels of infrastructure in remote northern communities, especially for Inuit and First Nations communities.

The special challenges facing remote communities are discussed in Chapter 29. To consider the difficulties inherent in funding infrastructure on reserves, both northerly and southerly, let us explore the particular case of water and wastewater on reserve.

Water Infrastructure on Reserve

Despite Canada’s status as the country with the most fresh water in the world, over 25% of reserves have substandard water or sewage systems.[1] Faulty water systems, necessitating advisories to either boil the water or avoid using it, have plagued First Nation reserves for years and have appeared in newspaper headlines time and again. Prime Minister Justin Trudeau pledged in his 2015 election campaign to end long-term drinking water advisories by March 2021. That didn’t happen, but significant progress was made; as of December 20, 2023, 143 long-term drinking water advisories had been lifted, 72 had been added, and only 29 remained, according to the federal government’s online progress tracker “Ending long-term drinking water advisories”.

The Auditor General of Canada analyzed federal spending on water systems in her 2021 report. She noted that, despite increased spending on water systems, federal support was still insufficient. She noted that the federal government’s own assessment of the riskiness of water systems on reserve did not improve between 2014-5 and 2019-20.

The Parliamentary Budget Office (2017b) has estimated that it would cost 3.2 billion to build or repair all the needed water and sewage infrastructure on reserves, and 361 million annually for operations and maintenance. In 2021 it estimated that promised funds up to 2026 should be enough to build all the necessary water infrastructure, but not enough for operation and maintenance of that infrastructure.[2].

Wells and Septic Beds:

Most rural Canadians who do not live on a reserve get their water from a well dug on their property. Their sewage is flushed into septic tanks and septic beds. Construction of a conventional septic system in Ontario cost about $18,000 in 2022; assuming the price of an average well is $10,000, we’d have a total bill of $28,000 per home.

Let’s round that up to $30,000 per home and multiply by 200, the size of a typical reserve community. That’s a price tag of 6 million dollars, significantly less than the 20 million we might expect for a water treatment plant without associated piping.

The federal government does not fund private wells and septic on reserve; it only funds water systems used by five or more households or wells used by the community at large. It does pay for septic trucks for a block of houses, for example $99,000 per block of 30-40 houses (in Manitoba, 2022).

Why do we not see more wells and septic beds on reserve? That’s something that needs to be explored. On some reserves, homes are too crowded together to make wells and septic beds possible, though septic tanks might be used. On other reserves, wells won’t work because the groundwater is contaminated by high levels of organic matter or industrial chemicals. On northern reserves, the soil may be frozen and unworkable. We should take a good look at what non-Indigenous neighbours do off-reserve and whether this can work on reserve.

The analysis that follows focuses on water purification plants and water treatment plants.

Water Systems on Reserve:

The Globe and Mail began a report on failed water systems in summer 2016, obtaining Indigenous and Northern Affairs’ records and interviewing engineers, project managers, and First Nations leaders. They filed a request under the Access to Information Act to get Indigenous and Northern Affairs’ Integrated Capital Management System database, which includes risk assessments for completed projects, plus a 2015 study done for Indigenous and Northern Affairs by Orbis Risk Consulting.

On the basis of this information, Matthew McClearn wrote several Globe and Mail articles, and Dean Beeby wrote another. They identified three major problems: lack of regulation, fragmented decision-making, and lack of expertise.

- Lack of regulation

Provincial regulations do not apply to reserves. Indigenous and Northern Affairs – now called Indigenous Services Canada – has water system regulations that are less stringent than provincial regulations. Modern municipal systems are built to provide 450 litres per resident per day, but many First Nation systems provide only 180 litres. But even if stricter regulations were imposed, there is still the matter of being able to achieve the standards in the regulations.

Graham (2018) originally supported the Safe Drinking Water for First Nations Act, which was passed in 2013 to establish water quality guidelines at the federal level, since reserves are not obliged to meet provincial requirements. However, he now understands why First Nations were opposed: the Act does not give First Nations any power to make rules, and it does little to lessen the burden of developing, maintaining and operating the water systems.

As of early 2021, no new regulations around safe drinking water had been formulated under this Act.

- Fragmented Decision-Making

- Indigenous Services Canada – decides whether to fund a project and roughly how much money to provide

- First Nation – decides on design

- First Nation – decides on a construction company. Construction company works with another firm’s design.

- Indigenous Services Canada – decides when to release the funds

- First Nation – responsible for operations and maintenance. Operators work with what the construction company has completed.

If Indigenous Services Canada were responsible for construction, it might send approval and funds more quickly.

If Indigenous Services Canada were responsible for service delivery, it might provide funds for more rigorous testing prior to design.

If the designer were responsible for construction, the design might be more practical. Most municipalities are now using the same firm to design and construct.

If the construction company were responsible for operating the plant for several years, it might take more care with the construction.

- Lack of Expertise

Most First Nation communities on reserve do not have members who can knowledgeably compare engineering proposals. Most reserves do not have or cannot attract skilled and experienced water systems operators. Most of Indigenous Services Canada’s engineers do not have much training or experience with water systems.

Even water system specialist engineers have failed to anticipate some of the complications in remote northern communities, such as permafrost, very cold ambient temperatures, acidic water, and very high dissolved organic matter content.

In addition to the three problems identified by the Globe and Mail, which we just examined, there are others:

- Piecemeal Approach

Another problem is that a project will be funded but the components needed in conjunction with it are not. So a water treatment plant may be built, but not the pipes taking water to the houses. Or houses may get hookups, but no wastewater removal or sewage pipes. Money for the water treatment plant is released, but not the money needed for operation.[3]

Meanwhile, the money which is released is typically only 80% of what is required for either construction or operations. It can be a struggle for Bands to come up with the remaining 20%.

According to the Auditor General of Canada (2021), the government uses a formula created in 1987, updated for inflation, to determine how much it pays for operations. Spending has depended on this formula, rather than on achieving goals and meeting quality standards. As a result of underfunding, in 2018 water systems operators on reserve earned 30% less than operators elsewhere.

- Size and Scale

On the matter of community size, Graham (2018) has questioned the ability of small communities to properly operate sophisticated systems, sharing the conclusion of the American Environmental Protection Agency that a minimum of 10,000 users is required for a viable system.

After the aforementioned Safe Drinking Water for First Nations Act was passed, the Atlantic Policy Congress, representing 30 Chiefs in the Maritimes, Quebec, and Maine, worked with the federal government to propose a regional water authority serving more than fifteen First Nations. In such an authority, Graham sees a way out of the current problems with water delivery.

A regional water authority for First Nations

- would take on the responsibility of providing quality drinking water, relieving Chiefs and Councils of legal liability

- could offer a more attractive employment package to qualified operators

- could operate multiple systems remotely to reduce costs per litre

- could be responsible for developing and installing new facilities, gaining experience and expertise along the way

Graham has proposed that this water authority be subject to laws developed by a First Nation Environmental Protection Agency. This agency, not yet in existence, could evolve to handle other matters as well, such as solid waste disposal. First Nations could decide whether or not to come under the auspices of this agency.

The Atlantic First Nations Water Authority became the first Indigenous-owned-and-operated water authority in Canada in 2022. It receives funds from Indigenous Services Canada and is reponsible for delivering clean water to seventeen member First Nations.

We have now discussed in depth the issue of water on reserves. The problems confounding water infrastructure generalize to other infrastructure such as electricity and internet. The solutions will likely generalize as well.

In fact, a First Nations Infrastructure Institute (see fnii.ca) is being developed to

- work with participating Nations who have signed on to the First Nations Fiscal Management Act

- walk participants through the steps of planning, acquiring, and maintaining infrastructure

- advise on best practices

- help participants to identify and manage risks

- offer insurance

- help participants strategize to raise money to pay for on-going operations costs.

- signal to investors, insurers, government funding agencies, and business that a First Nation project is sensible and shovel-ready

This Institute will not deal with residential housing. We consider that challenge in our next chapter.

Public goods are goods which are accessible to all and where one person's use doesn't interfere with another person's use. When one person's use does interfere with another person's use, the good in question is no longer a public good in the economic sense.