Economies prior to the late 20th Century

We have just reviewed the unique taxation considerations for Status persons. These considerations help explain how some reserves have been able to sell alcohol and cigarettes at a discount to the general public. More recently, cannabis has been added to the mix. Some First Nations have also established casinos.

This chapter, which discusses casinos and cannabis sales continues the previous chapter’s discussion of taxation. Instructors may wish to leave this chapter until later in the course.

Briefly, here is what casinos and cannabis have in common:

- for much of Canada’s history, gambling and cannabis use were considered vices; there is still some stigma attached to them

- gambling and cannabis use have associated social problems including addiction

- First Nations’ ambiguous legal status helped them offer gambling and cannabis when these were still illegal for non-Indigenous Canadians; these services were in short supply and therefore profitable

- gambling and cannabis have been legalized fairly recently

- provinces and territories have authority to license casinos and cannabis vendors

- First Nations are not allowed to regulate their own casinos or cannabis vendors

- provinces are in charge of regulating casinos and cannabis, but some provinces also run casinos and sell cannabis, creating a conflict of interest

- the provincial governments’ stake in casinos and cannabis likely reduces government’s attention to social problems associated with the two industries

- the provinces do not allow much competition in these two businesses

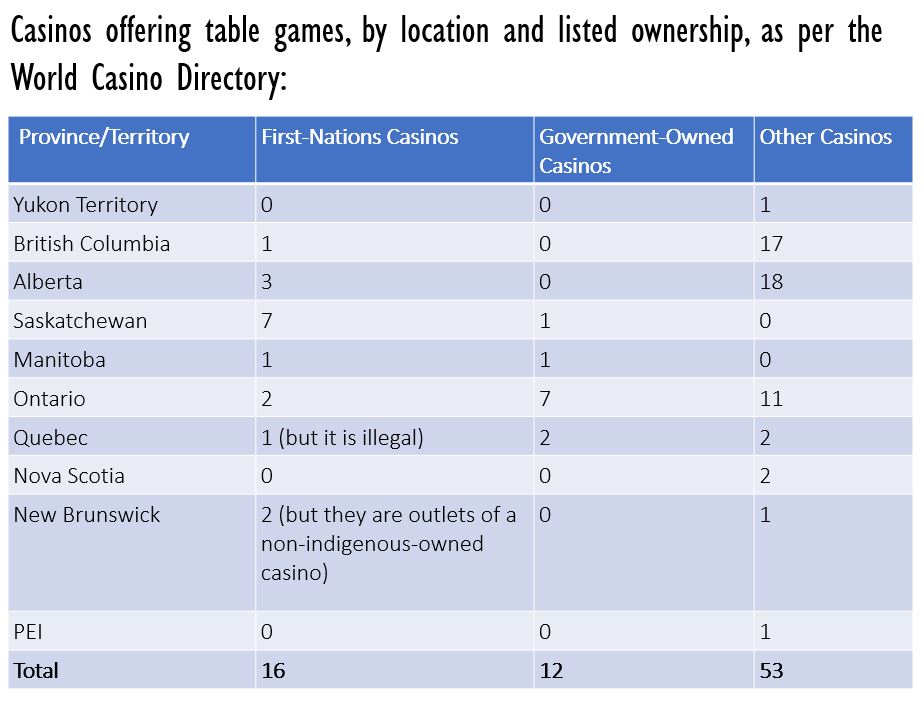

Let’s begin with casinos, which are for-profit gambling activity centres. These were legalized before cannabis was legalized. This section on casinos relies heavily on Tom Flanagan’s paper “Cartels and Casinos: First Nations’ Gaming in Canada” (2020). Flanagan tells us that gambling was illegal in Canada until 1985, but some forms of gambling, such as horse racing, charitable fundraisers, and games of chance at county fairs and exhibitions were permitted. In 1985 the Provinces were given the right to decide for themselves whether and how to legalize gambling. All the provinces chose to legalize gambling, and to give themselves the right to license and regulate the industry. The main reason that casinos require regulation and monitoring is the potential for “money laundering”. Money laundering is the exchange of money earned in crime for money that cannot be traced to a crime. At casinos, criminals can buy gambling tokens known as chips with their dirty money, then cash in the chips for clean money.Other problems associated with casinos are citizens gambling irresponsibly and impoverishing themselves and their families, and the activities of thieves, prostitutes, pimps, drug dealers and con artists attracted to a scene of extravagant spending. After the provinces legalized gambling in 1985, several First Nations opened their own casinos, citing Canada’s newly revised Constitution (Constitution Act, 1982). Section 35 of this Act safeguards “aboriginal, treaty or other rights that pertain to the aboriginal people of Canada”. However, in 1996 the Canadian Supreme Court ruled that high-stakes gambling was not a traditional practice and thus is not an Aboriginal right.There being no longer a legal grey zone for First Nations casinos, First Nations had to negotiate with the Provinces to keep their casinos legal (under contemporaneous Canadian law). Provinces can decide whether a casino may operate, where it may operate, how many and what kind of games it can offer, how much it can profit from games, and what proportion of profits it can keep for itself.

Meanwhile, several provinces operate their own casinos. These provinces have an extra reason to reduce the number of casino licenses granted. They also have an incentive to keep the best locations for themselves. Most Canadian cities do not have a First Nations full-service casino; Calgary and Edmonton are the two exceptions.

Belanger (2018) determined that in 2016, after provinces took their share of profits from gaming, 750 million dollars remained with gaming First Nations, was put in Trust for those First Nations, or was shared with other First Nations. About 300 communities in total were impacted. In Saskatchewan in 2019, the average grant to a First Nation from shared gaming profits was likely around $700,000, “a welcome addition to a band’s budget but not a game changer.” (Flanagan 2020).

For First Nations hosting large casinos within or not too far from major cities, the revenues may be more significant. Enoch Cree First Nation, home of River Cree Casino in Edmonton, reported an operating surplus of 32.3 million dollars in 2019. Tsuut’ina First Nation, which hosts Grey Eagle Casino in Calgary, reported a 2015 operating surplus of 34.1 million. In Orillia, Ontario, the Chippewas of Rama likely made about 32 million in gross revenues from Casino Rama in 2019.

Flanagan examines whether having a casino gives a First Nation better income, employment, housing, and educational achievement as summarized by the Community Well-Being Index. There is not enough data for statistical regression analysis, but tracking a community’s CWB over time and how it changed after the community opened a casino, Flanagan tentatively concludes that successful casinos contribute to First Nations’ well-being. Communities which benefited the most are those which have casinos in or near urban centres, and/or casinos located with a resort or multiple other business developments nearby.

He concludes by urging the government to allow First Nations to open and manage gaming as they please, presumably with shared oversight related to crime and addiction prevention; if not that, to free up the market to all entrepreneurs; if not that, to allow First Nations more access to urban and resort locations for their casinos; and if not that to at least allow First Nations to keep a greater share of gaming revenues.

Flangan’s first recommendation would privilege First Nations over other casino operators, and we could reasonably debate the merits of that proposal. The other three recommendations are more egalitarian. What do you think?

Cannabis:

Cannabis is an herbaceous plant from Central Asia. The subspecies of Cannabis known as “marijuana”, “pot”, or “weed” contains the medicinal and psychotropic chemical tetrahydrocannabinol (THC).

In 1910, during the Mexican revolution, recreational use of cannabis became more prevalent in North America, so that by 1923 Canada had made the use of cannabis illegal. In the 1960s recreational cannabis use became popular. In 2001, cannabis use was legalized for medicinal purposes. At this point some First Nations began to sell cannabis on reserve to both on-reserve and off-reserve customers, often not requiring any assurance that the cannabis would be used medicinally.

The Mohawks of the Bay of Quinte were one such Band. In 2019 the owner of Legacy 420, the largest cannabis retailer there at the time, told a visiting class of students that he believes the Simcoe Treaty (Treaty 3.5) gives him the right to run his business without a license from the province of Ontario, “freely and clearly of and from all and all manner of Rents, Fines or Services.” The Two-Row Wampum and Treaty of Niagara imply similar independence.

Other First Nations, who did not sign treaties that might be interpreted as giving them a right to free enterprise, might interpret cannabis growing and selling as a natural extension of their traditional practice of growing medicines, and thus a specific Aboriginal right. Or they might argue that cannabis growing and sales are supported by a generic right to use traditional lands in keeping with the early treaties, inherent rights to self-government as per section 35 of the Constitution Act (1982), and inherent rights to self-determination as per Article 3 of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (2007).

Aware of these interpretations, the federal government chose not to prosecute First Nations cannabis vendors. This decision might also have been motivated by a willingness to see business, any kind of business, thrive on reserve.

In 2018, Canada legalized the recreational use of cannabis. There was now an opportunity to legalize all growing and selling that was already taking place. Instead, only government-sanctioned growers and sellers of cannabis have been legalized. Health Canada licenses growers, and the Provinces and Territories license vendors.

Unfortunately, seven provinces have elected to run their own cannabis retail outlets, which means they are trying to make money selling cannabis for themselves while supposedly treating all vendors equally. The provinces which run retail outlets now have an incentive to restrict the number of licenses they issue, and to keep the most favourable locations for themselves.

Licensed growers must pay the federal government 15% of the value of the product when they first sell it. None of this excise tax is shared with First Nations.

While the Cannabis Act (2018) allows for the government to negotiate all aspects (growing, marketing, selling, taxation) of the cannabis trade with First Nations, it did not consult First Nations prior to the creation and implementation of the Act, nor had it yet come to any general agreement with First Nations two years later.

However, in 2020 Williams Lake First Nation became the first First Nation to have a business licensed to grow cannabis. Meanwhile, many First Nation businesses had been licensed to sell cannabis. In Ontario, 8 of the 65 licenses issued before 2020 were for First Nations.

Flanagan’s proposals for casino deregulation could be applied to the cannabis market: that the government allow First Nations to grow and sell cannabis as they please, with some joint oversight on quality of product and advertising norms; if not that, to free up the market to all entrepreneurs; if not that, to allow First Nations more access to urban locations for their cannabis businesses; and if not that, to share excise tax revenues with First Nations or formally exempt them from excise taxes.

It seems reasonable that provinces could give up some of their control and revenue in favour of economically-disadvantaged First Nations.

However, there are also arguments to be made for discouraging the growth of the cannabis sector in any form. Cannabis, like casino gaming, is likely to remain controversial.

Having surveyed the history of Indigenous economies prior to the twentieth century, and having examined the Indian Act and its implications, it seems right to pause and consider the role of racism and discrimination in economic outcomes. That is the focus of our next two chapters.

As described in Chapter 2, the CWB is an index number that scores communities on their housing quality, educational achievement, employment, and income.