Economies prior to the late 20th Century

Let’s pick up the historical thread in 1800, where we left off at the end of Chapter 6. By 1800, fur was no longer the staple export from British-controlled Turtle Island; logging had become its dominant industry and timber its primary export. While the East was busy with logging and farming, the centre of fur collection had moved to northern Manitoba.

Gradually traders and trading posts had penetrated the West. But beyond Toronto, population 300, there was no European-style settlement in Western Canada at all except for a community of mixed ancestry living at the junction of the Red River and Assiniboine River where Winnipeg stands today. This was the birthplace of the Métis Nation.

We have previously spoken about the lifestyle of the Bison Hunting Peoples indigenous to this region. Now a few words about the Métis. It is not generally appreciated that it was mixed race individuals, not so much Europeans, who on behalf of European interests explored Canada and opened it to trade. This had to be the case due to the fact that there were almost no white women in Canada for a hundred years after first contact. John Bentley Mays (2002) writes:

“…in 1791, Ontario’s British population…was concentrated at Kingston and Niagara-on-the Lake, with a sprinkling of new towns and farming communities near the Bay of Quinte [current-day Belleville, Ontario]. In the rocky wilderness beyond the fertile hill country of the lower Great Lakes basin lay only a handful of towns – if one can call a huddle of cabins a town. As recently as the 1860s, the outposts of Sault Ste. Marie, Fort William [now Thunder Bay], Fort Frances and Rat Portage – as Kenora was known then – were among the very few settlements in that northern vastness.

But this is certainly not to say that those endless tracts of swamp, lake and thicket were innocent of human life. The Aboriginal people knew and loved this country. So did the spiritual offspring of Étienne Brûlé, those trappers and hunters who had once been French but had long since melted into the forests and become a race of folk more Christian than pagan. Too distant from the institutions of French Christian civilization to think much about them, most nevertheless kept the names of their French ancestors – Chevrette, Boyer, Côté, Cadieux…- who had been coming up from Montreal along the Ottawa River in their shallow-draft boats to Lake Huron since 1608, when Champlain dispatched Brûlé to make the first, critical contact with the western Wendat. The voyageurs brought from the western edges of European civilization the trade goods valued by the ancient nations dwelling inland: guns, buckshot, bullets and gunpowder above all, but also copper chaudières, iron tools, wire.

They also hauled daintier things, much treasured by the inland peoples: the porcelain beads known as rasade, mirrors and bells, combs and earrings. They hauled over the portages, then downriver to Ville-Marie [Montreal] the precious pelts that shaped the economy of New France.”

Meanwhile, in the vicinity of Hudson Bay, Hudson Bay Company (HBC) traders were having children with Indigenous women. These “Country Born” mixed ancestry children stayed closer to home. Writes the Canadian Geographic[1]: “Many sons of HBC traders also became fur trade employees, serving in a variety of positions such as clerks, postmen and factors. These English or British Métis were less likely to be involved in labouring positions such as manning York boats than their French Métis compatriots.”

It was mixed race people moving west, not Europeans, who were the first non-First Nations to settle in the confluence of the Red River and Assiniboine River, at present-day Winnipeg.

In the first half of the nineteenth century, intermarriage resulted in a fusion of French-Indigenous and Country-Born lineages. The two groups recognized common cause against the encroachment of settlers and the monopoly of HBC on trade.

The new Métis culture merged French, Algonquin, other Indigenous, Irish, and Scottish traditions. Dancing, fiddling, decorated clothing and horse tack, and a language (Michif) incorporating French nouns and Cree or Ojibway verbs are noted elements.[2]

Métis spiritual beliefs have traditionally aligned with Catholic Christianity, influenced by native, particularly Algonquian spirituality as can be seen in the Michif words for God: Li Bon Jeu (French: The Good God), Kitche Manitou (Algonquin languages: The Great Spirit), and Not Kriiteur (French: Our Creator). [3]

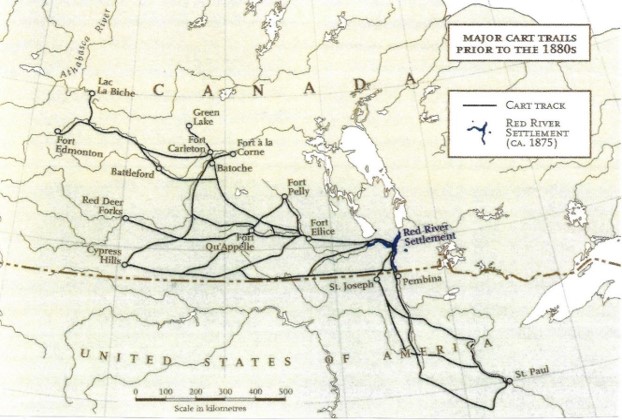

The original Métis lifestyle was flexible and diverse. Trapping, hunting, fishing, bison hunting, pemmican (dried meat trail mix) production, and farming were among the occupations chosen. The Métis were also traders, and providers of canoe and cart transportation.

It is likely that the presence of Métis would have interfered with First Nations’ hunting and fishing, especially in the prime hunting and fishing grounds along the Red River and southern Lake Winnipeg. Maureen Matthews (2017) writes that the Métis living here often conflicted with the Assiniboine on the prairies. Thus when Selkirk brought British settlers to the Red River area, “he introduced a destabilizing element into an already unstable and occasionally violent social situation,” one in which Métis, allied with the North West Company, competed with Assiniboine, Cree and Ojibwe peoples, traditional HBC clients.

Lord Selkirk was a Scottish lawyer and social activist intent on settling Scottish farmers who had lost their lands in the wave of evictions known as the Highland Clearances. He generously used his own inheritance to buy land in what are now Prince Edward Island and Ontario for the refugees. He also purchased enough shares in the Hudson’s Bay Company to help him negotiate 116,000 square miles of the Red River valley for Scottish settlement, with the first settlers arriving in 1811 and the Scots/Irish settler population numbering about 221 in 1821.[4] Unfortunately, Selkirk’s plans did not include consulting or compensating the Métis living there. In the coming years Métis property boundaries would be ignored and Métis hunting and trapping and commercial activity would be constrained and regulated. The response of the Métis alternated between patient petitioning and restrained shows of force.

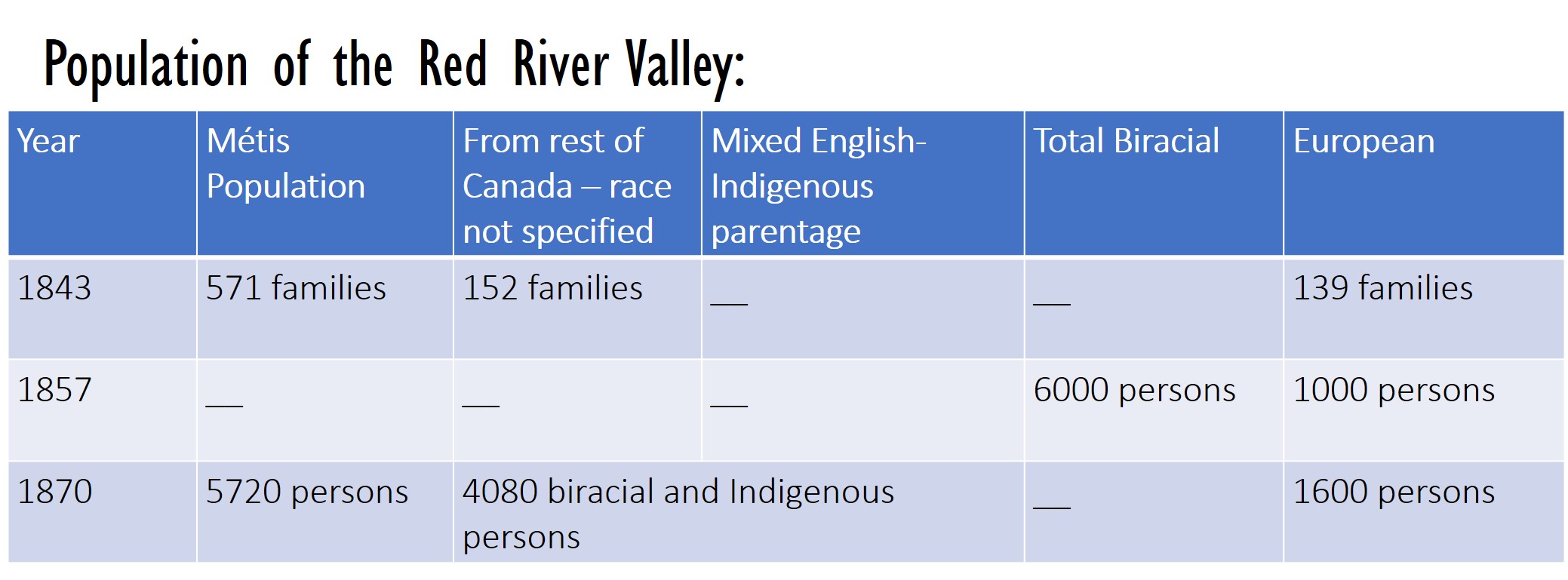

The chart below shows that Métis people continued to form the majority of the population in the Red River Valley during the nineteenth century until at least 1870.

Confederation:

In 1867, the provinces of New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and “Canada” (a.k.a. Ontario and Quebec) united to become a Nation independent of Britain. This new country was the Dominion of Canada. Canada’s new constitution, the British North America Act, asserted that the government of Canada would now have authority over “Indians, and lands reserved for Indians”. “Indians and lands reserved for Indians” was the twenty-fourth item in a list of 29 items coming under federal jurisdiction. The list also included the Census, banking, and the postal service. No other mention was made of Indigenous peoples in this Constitution.

Tom Courchene (2018) has noted that the government has tended to interpret its legislative powers and responsibility as pertaining to “Indians, on lands reserved for Indians”, ignoring Indigenous people who are not on reserves.

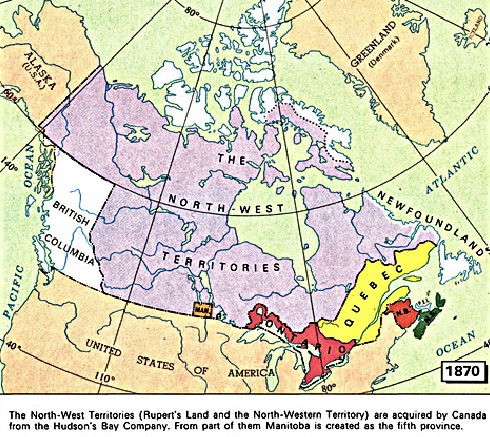

Two years after Confederation, the Hudson’s Bay Company surrendered Rupert’s Land to the British Crown, which gave the land to Canada. The HBC received $1.5 million and got to keep its trading posts plus 20% of the farmland, about seven million acres. The seven million acres is more than double the approximately 3 million acres that would eventually be set aside for First Nations (Yellowhead Institute, May 2021). No Indigenous people were involved in this negotiation.

Without Rupert’s Land, the new Canada would have ended in Ontario, and excluded most of what is today northern Ontario and Quebec. With Rupert’s Land, Canada became a much larger country, on the same scale as the United States, a country potentially stretching all the way to the Pacific Ocean.

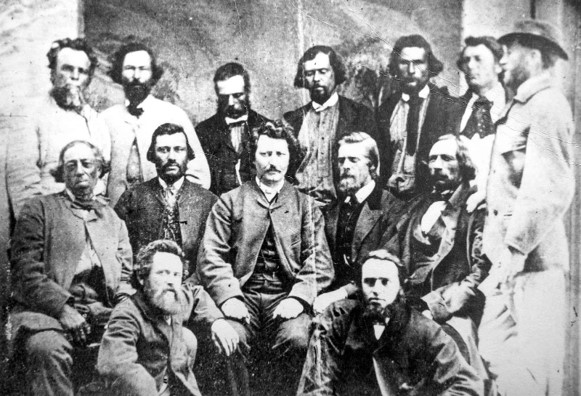

Even before the deal was signed, surveyors began to divide up the new territory for immigrant farmers from eastern Canada, in complete disregard for First Nations or Métis rights. So it was that, in the fall of 1869, a young man named Louis Riel stopped surveyors from continuing their work on Métis property.

Riel formed the “National Committee of the Métis of the Red River” shortly thereafter, and with a force of 500 men he non-violently took over the local colonial office and the local Hudson’s Bay Company administrative office at Fort Garry. The group proceeded to form a local government. They also drafted a Bill of Rights, an expression of native rights within Canada.

Riel was not the only one in his community with spunk. Anna Bannatyne and her husband were the first merchants in the Red River community who were not HBC traders. Anna was a founder and fundraiser of what is now the Winnipeg General Hospital. In 1868 she hosted a politician named Charles Mair. He or his brother submitted a piece on his Red River trip to the Toronto Globe newspaper, wherein he made derogatory comments about Métis women, calling them for example “homely half-breeds.”

When next time he showed up on Bannatyne’s property (1869), she grabbed a horsewhip and lashed him several times, shouting, “That’s how the women of Red River treat those who insult them.”[5]. This may have been a sign to Riel that his people were ready for action.

Within a year of Riel forming a government at Red River, Ottawa responded by negotiating the creation of the province of Manitoba, recognizing the Métis’ Bill of Rights and promising 1,400,000 acres of land to the Métis. The only fatality of what is now called the Red River Resistance[6] was a prisoner named Thomas Scott who was executed by the Métis. Mostly because of this execution, many voters in Eastern Canada looked with disfavour on the Métis and believed that the government had been too soft on “rebels”.

With the establishment of Manitoba, settlement of the West accelerated and tensions rose. That very year, one thousand soldiers under Colonel Wolseley were sent to the Red River to calm things down. Instead of stabilizing the situation, Wolseley’s force wreaked havoc among the Métis, including rape and murder. About half the Métis left Manitoba and moved west into what was then called the “North West Territories”. In 1875 this area was organized under its own Act, as usual without any recognition of Métis presence. In the years to come, Métis living there would petition the government for formal title to their lands, and for political representation, but to no avail.

Meanwhile the promised distribution of land in Manitoba to Métis was disappointing. New lands, not original properties, and lands separated by miles, were dispensed on an individual basis, often in new territory west of the Red River.

As a result, the Métis ended up with a small fraction of the land intended for them. The Supreme Court of Canada would rule in 2013 that Canada failed in its commitment to the Manitoba Métis.

The Demise of the Bison:

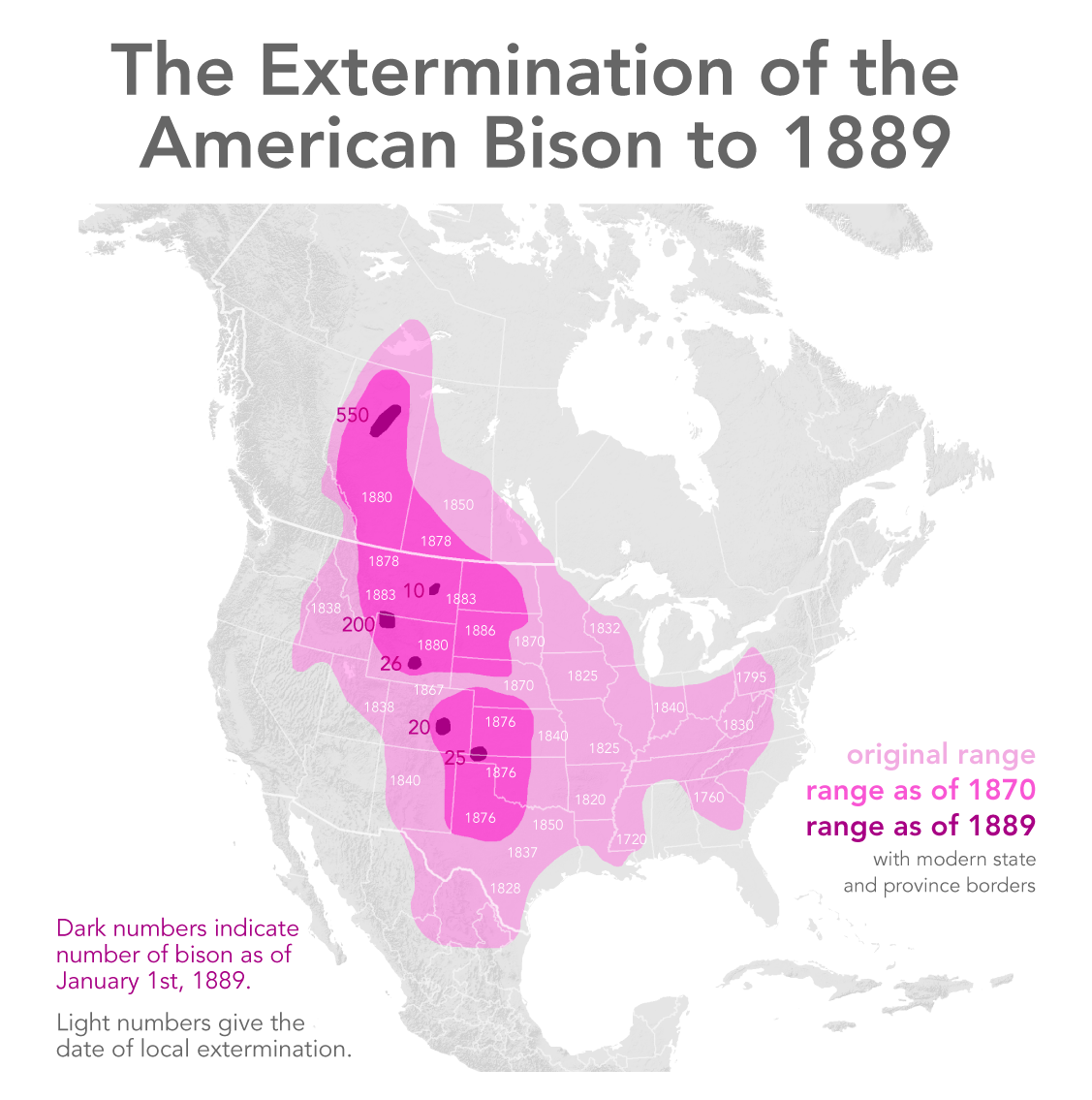

It is during this time, the 1870s, that the virtual extinction of the Bison was taking place. In about twenty years the great herds were finished off. Settlers and their cattle were pouring into bison habitat, especially south of the border via the United States’ new Northern Pacific Railroad, completed in 1876. Some rode the train just to shoot at bison.

The railway had an interest in reducing the herds which could potentially block the tracks.

The US Army tolerated or encouraged the killing of bison as it sought to control the South West. Treuer (2014) claims that both soldiers and American civilians were paid bounties for each bison killed, with the skulls presented as evidence.

Moreover, a new method of tanning bison hides had been developed, so that bison leather could be used to make belts for steam engines. Where no hides at all had been exported in 1870, one million hides were exported to Britain and France five years later.

The decrease in bison numbers between 1730 and 1889 is shown by the map below. Some areas had lost bison gradually, possibly due to the arrival of rifles, horses, and European cattle diseases. Other areas lost the bison rapidly in the surge of settlement and industrial hunting just described. Carter (1993) asserts that by the 1870s, many reports from various sources were warning the federal government that bison were endangered. The government was advised, for example, to restrict bison hunting to Indigenous people, and to prohibit the export of processed bison products. It did not.

In their paper The Slaughter of the Bison and a Reversal of Fortunes on the Great Plains (2017), Feir, Gillezeau and Jones estimate the short- and long-term impacts on Plains Nations from the loss of the bison and the deprivations which followed.

First, they analyze data on the height of Indigenous North Americans and Siberians collected by the anthropologist Franz Boas between 1889 and 1903. Men from communities whose traditional territories overlapped the original bison range by more than 60 percent had a height advantage of more than three centimeters over men from non-bison-dependent communities. However, if these men were born after 1870, they were no taller than the other Indigenous men. This means that within one generation, lack of nutrition literally cut down formerly bison-dependent Plains people. Given that the most-stunted people would have died and not been included in the sample, the decrease in height understates average nutrition loss. Feir et al. then look at American data and find that:

- In the year 2000, formerly bison-dependent communities earned approximately 30% less GDP per person than other Indigenous communities.

- Using satellite night-time light data to proxy GDP for small communities (which do not publish GDP data) yields the same conclusion.

- Even individuals identifying as members of formerly bison-dependent tribes who are no longer living on reserve have lower incomes than other Indigenous individuals.

- Nations that lost the bison slowly had lower occupation rankings in the 1910 and 1930 censuses than other Indigenous nations, but by the 1990s had rankings similar to the US national average.

- Nations that lost the bison quickly had lower occupation rankings in the 1910 and 1930 census than other Indigenous nations and still have lower occupation rankings, though the differences have moderated over time.

- Nations that lost the bison quickly were more likely to be in the news between 1991-2000 for social conflict and/or corruption in the community

The authors conclude: “This finding suggests that the rapid loss of the bison acted as an immediate shock to well-being and that this shock was transmitted intergenerationally”. Evidence of past and ongoing problems on the Canadian Prairies is found in the lower Community Well-Being scores of Prairie First Nations. In 2016, Prairie First Nations had the lowest CWB scores in all of Canada, and the highest gaps vis-à-vis non-Indigenous communities.[7]

Evidence of past and ongoing problems on the Canadian Prairies is found in the lower Community Well-Being scores of Prairie First Nations. In 2016, Prairie First Nations had the lowest CWB scores in all of Canada, and the highest gaps vis-à-vis non-Indigenous communities.[7]

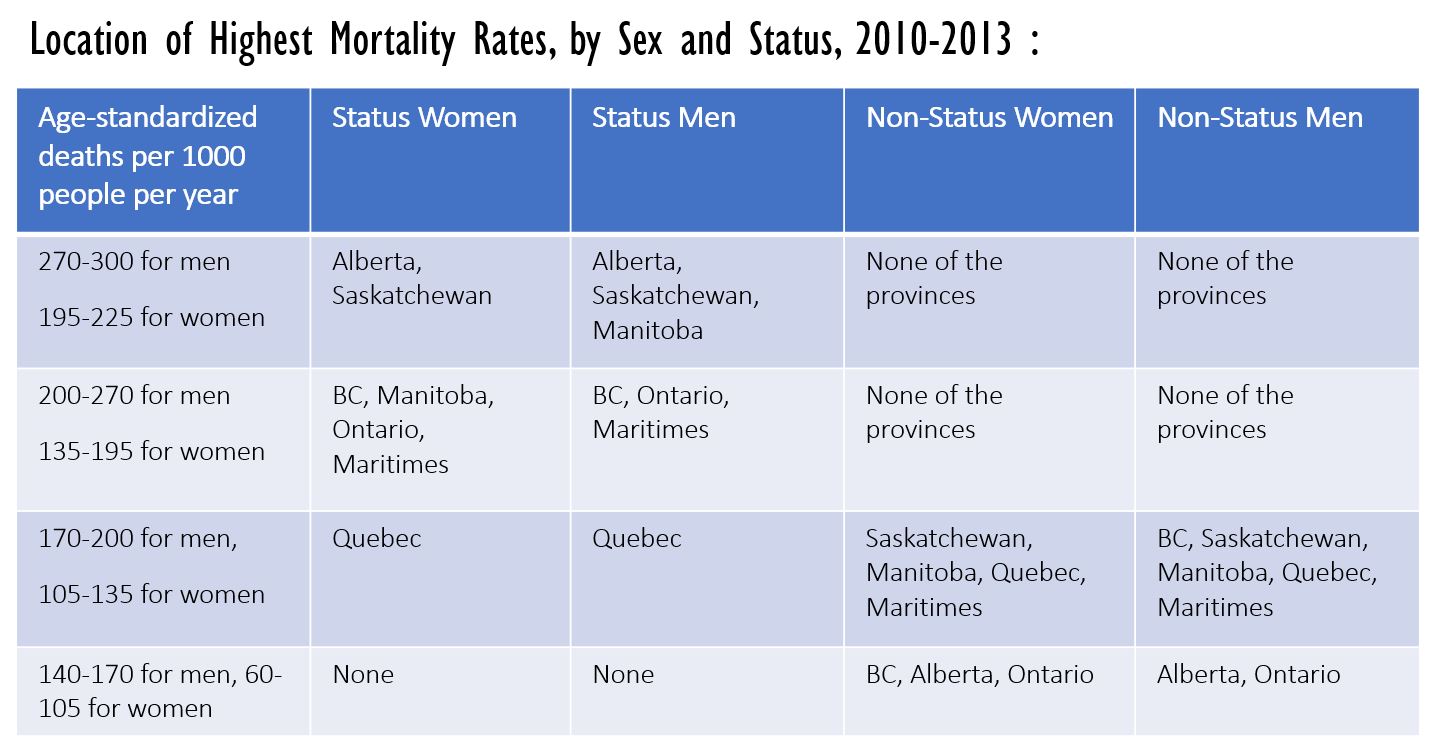

The Prairie disadvantage also shows up in the mortality rate research of Akee and Feir (2018). The chart on the next page, based on their data, shows mortality rates across Canadian provinces, for ages 5-64. The mortality rate has been age-standardized to account for the fact that some provinces have fewer young people and more older people than other provinces. The highest mortality category is between 270 and 300 deaths per 1000 per year. Only Status men living in Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba have rates that high.

The highest mortality category is between 270 and 300 deaths per 1000 per year. Only Status men living in Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba have rates that high.

The next highest category is between 200-270 for men and 195-225 for women. That only occurs for men in BC, Ontario and the Maritimes, and for women in Alberta and Saskatchewan. Akee and Feir show that economic and social conditions explain the mortality issues in Alberta and Saskatchewan for Status women, but cannot explain the high mortality for Status men in Alberta. Alberta is one of the safest provinces for non-Status men.

Status men and women are doing better in Quebec, the only province where they have death rates similar to non-Status men and women. Akee and Feir find that Quebec mortality rates are lower for Status people even after adjusting for social and economic conditions. Similar to these results are those of Beedie, Macdonald and Wilson (2019), who find that 2015 Indigenous child poverty rates are highest in Saskatchewan and Manitoba, and lowest in Quebec.

About forty per cent of Canada’s First Nations live on the Prairies. When we think about intergenerational trauma, we usually think of something bad happening that affects parents, who therefore are less able to provide a positive experience for their children, who grow up to be parents with less to offer, and so on. We sometimes forget that subsequent generations may be experiencing new shocks of their own. This was indeed the case on the Plains. The extirpation of the bison was followed by policies which served to lock subsequent generations into poverty. These will be the subject of our next chapter.

As described in Chapter 2, the CWB is an index number that scores communities on their housing quality, educational achievement, employment, and income.

A legal status identifying someone as being descended from First Nations who made a treaty or some other agreement with the government of Canada.

Intergenerational trauma is harm that is experienced by the descendants of someone who has been harmed, as a consequence of that first harm.