Economies prior to the late 20th Century

In this Chapter we’ll discuss the early years of contact and move all the way through the eighteenth century to cover trade, conflict, and treaty-making.

The very first contacts between the Indigenous Peoples of present-day Canada and Europeans were probably sporadic and tentative. The Inuit traded iron with the Norse in Greenland. Vikings lived briefly in what is now Newfoundland before apparently being driven away by the Inuit or Innu.

In the fifteenth century, Europeans began to venture further from home. By 1500, Columbus had landed in the Bahamas and various Europeans – Basque, Bretons, Normans, English, and Portuguese – were fishing for cod in Newfoundland’s waters. No settlement on Turtle Island had yet been established.

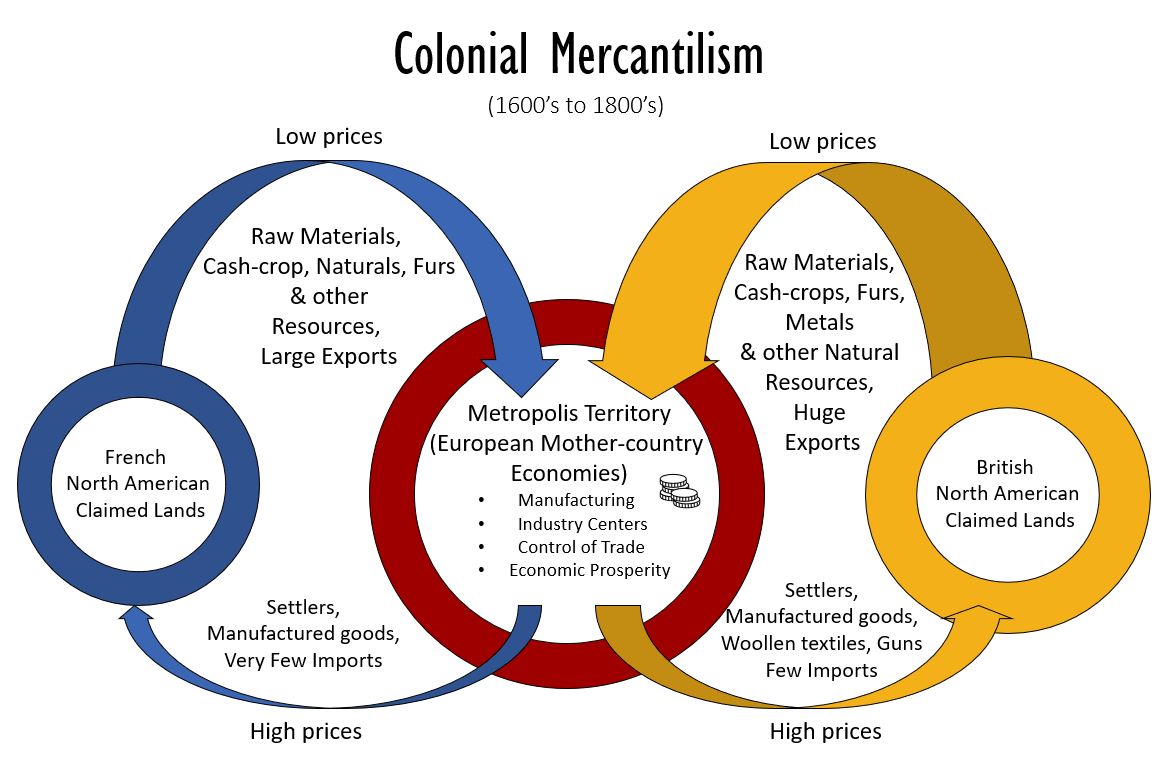

That would soon change as European states continued to fund explorations with the goal of expanding trade routes and establishing colonies. They were driven by Mercantilism, so named by the first academic economist, Adam Smith. Mercantilism is the belief that there is one winner in every transaction: the seller. The goal of trade is therefore to acquire the most money. What do you think is the goal of trade?

According to the mercantile way of thinking, a nation wants its terms of trade (the value of its exports divided by the value of its imports) to be as high as possible. Thus, each colonial power attempted to be the exclusive purchaser of raw materials from its colonies and the exclusive seller of finished products to its colonies. This led to intense conflict between the French and British on Turtle Island, into which conflict Indigenous people were recruited. First Nations themselves understood the value of trade routes and monopoly power and vied with each other to control access to trading opportunities.

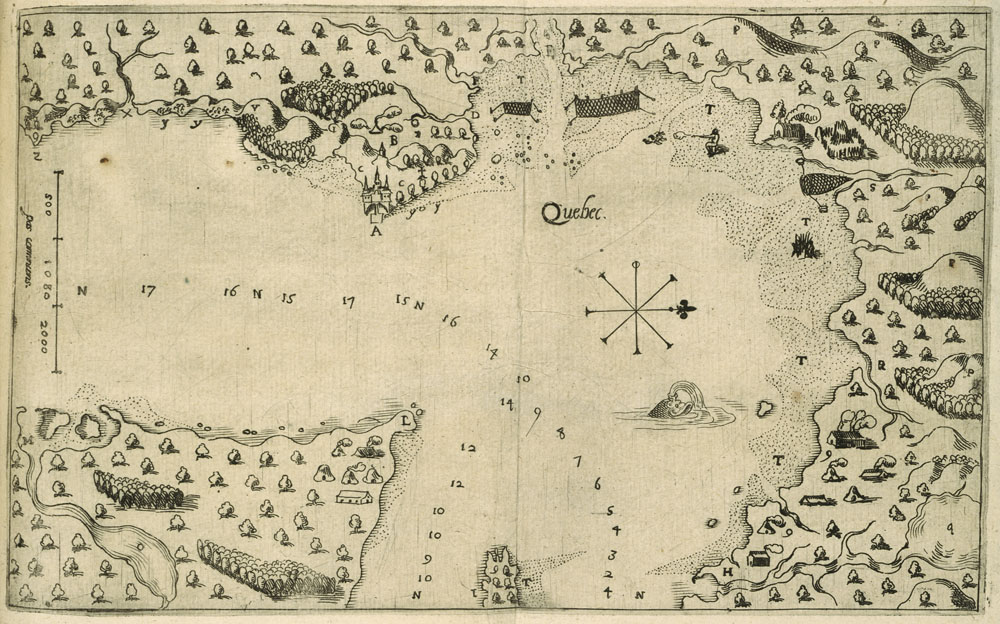

In 1534, Jacques Cartier of France entered the Gulf of St. Lawrence. He and his companions met members of the Wabanaki Confederacy, which comprises the Mi’kmaq, Maliseet, Passamaquoddy, Penobscot and Abenaki, traditional inhabitants of the Gulf of St. Lawrence. He also met the Stadacona, an Iroquoian people living further west along the St. Lawrence River. He annoyed the Stadacona by setting up a large cross in the name of the King of France.

That the King of France would feel entitled to a foreign, inhabited land is explained by the Doctrine of Discovery, the then-prevailing legal opinion that Christian nations could claim newly discovered lands as their own even if inhabited, so long as the inhabitants were not also Christian. Based on papal pronouncements such as Inter Caetera (1493), the Doctrine of Discovery rationalized Europeans’ rivalrous acquisition of colonies.

Cartier came back a second time, admiring farms at the Stadacona base (now Quebec City) and at Hochelaga (now Montreal). He kidnapped several Stadacona and took them to France, where most died. When he came back for a third time, the Stadacona were no longer friendly – surprise, surprise – and sabotaged his attempts to establish a French settlement at “Kebec”.

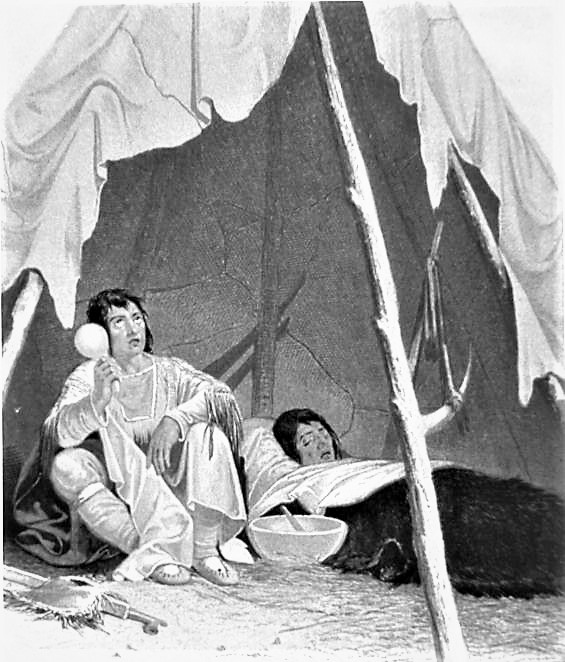

By this time European diseases may have taken hold of the Stadacona. About 70 years after Jacques Cartier, Samuel de Champlain of France would explore the St. Lawrence River and find no Iroquoian people whatsoever. Let’s pause to consider the terrible toll that contagious disease took on Indigenous peoples.

Disease from Europe:

Diamond (2012) explains that Europeans carried a particular class of diseases that can only be sustained by large populations. A “Crowd Disease” or “Acute Immunizing Crowd Epidemic Infectious Disease”, such as smallpox and measles, survives only in human bodies. Victims either rapidly die or acquire lifetime immunity, so the pathogen must stay alive by moving from one area to another searching for new victims. That is why the pathogen can only survive in large populations. Do you think COVID-19 is such a disease?

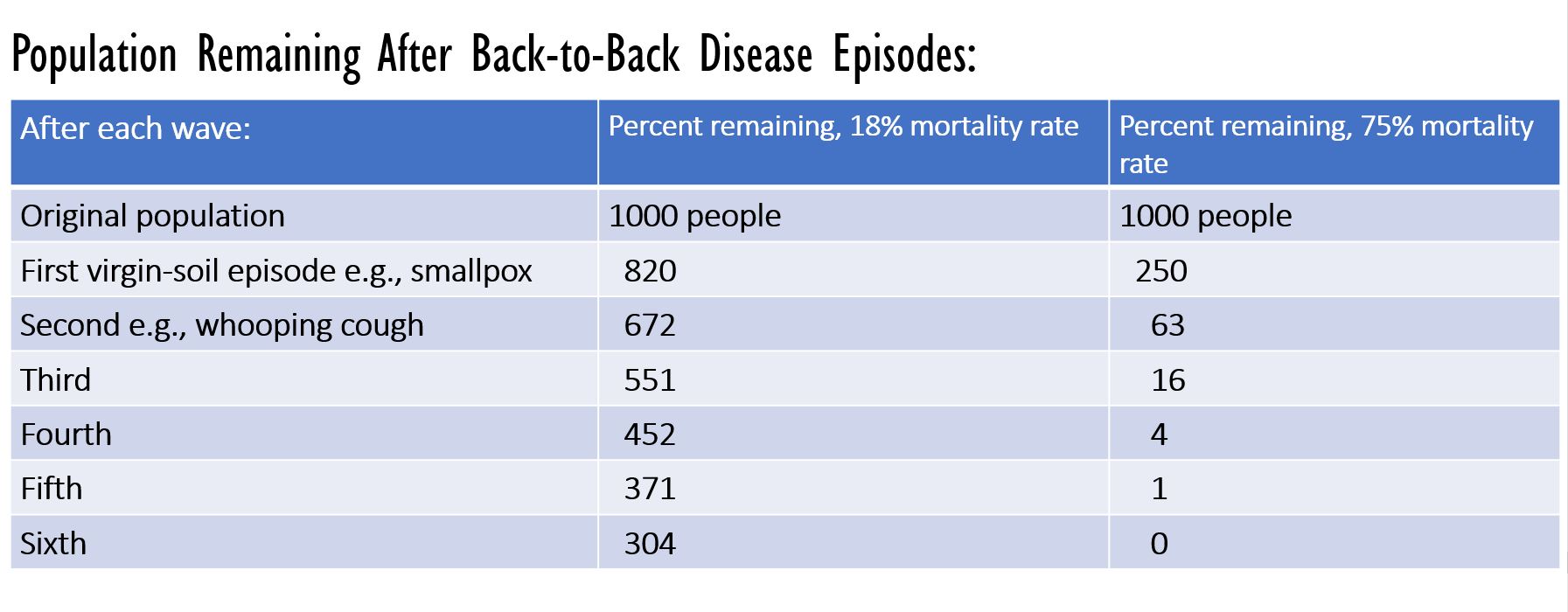

Cobb (2016) and others claim that some epidemics triggered by newcomers to Turtle Island resulted in mortality rates as high as 75%.

But such high mortality rates have never been officially documented anywhere in the world and would leave so few survivors that most communities would rapidly disintegrate. A more reasonable estimate can be found in Carlos and Lewis (2012), who use four different techniques to conclude that roughly 18% died during a virgin soil[1] smallpox episode near Hudson Bay in 1781.[2] Wave after wave of 18% mortality – first from smallpox, then from whooping cough, then from measles for example – could do enough damage to explain rapidly declining Indigenous populations. A calculation, assuming no breaks between epidemics, illustrates this:

Ignace and Ignace (2017, p. 457) record an account of 59 deaths from the Spanish flu (1918) in a Secwépemc village of about three times that many people, implying a 33% death rate. That very large mortality rate could be accurate; factors such as poverty, treatments, or concurrent crises may have compounded what otherwise would have been a lower mortality rate.

Ignace and Ignace (2017, p. 457) record an account of 59 deaths from the Spanish flu (1918) in a Secwépemc village of about three times that many people, implying a 33% death rate. That very large mortality rate could be accurate; factors such as poverty, treatments, or concurrent crises may have compounded what otherwise would have been a lower mortality rate.

The successive waves of epidemics did indeed lead to terrible population losses. For example, the Secwépemc population declined by 67% between 1850 and 1900, according to a careful study by ethnographer James Teit (1909, pp 464-6).

First Settlements:

The seventeenth century was the century of permanent European settlements on Turtle Island. In 1604, Samuel de Champlain of France began to establish French settlements, first at “Acadia” (Nova Scotia) and then at “Kebec” (Quebec City).

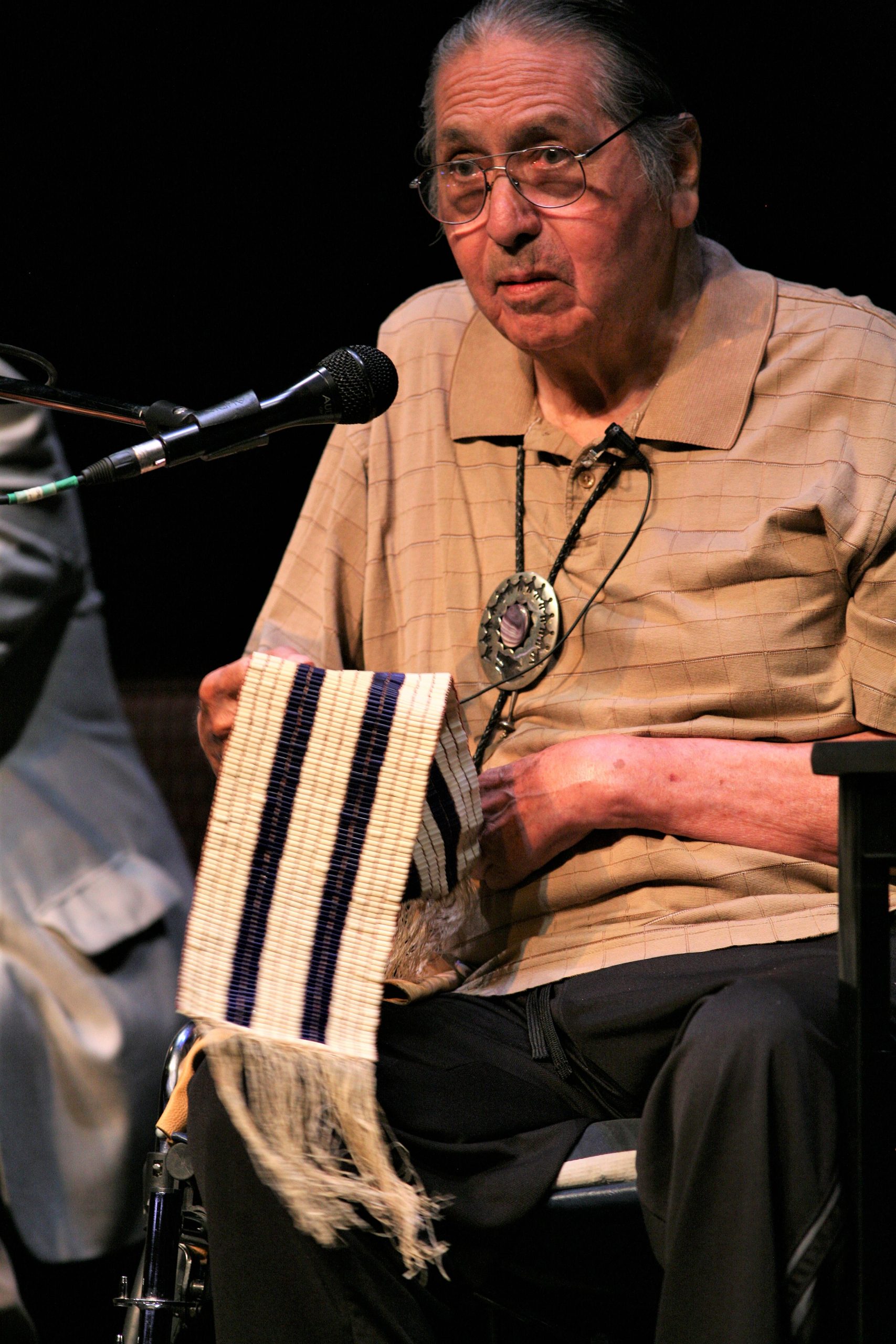

In 1609 Henry Hudson (working for the Netherlands) landed at what would be called first Nieuw Amsterdam, then later, New York City.[3] The Dutch negotiated the first European-Indigenous treaty in North America. This, the Two-Row Wampum Treaty of 1613, was a treaty of non-interference with the Kanienkehá:ka and their allies within the Haudenosaunee.

The wampum belts made for the occasion depict two nations, each going down its respective path, side-by-side, but separate. The Haudenosaunee became trading partners of the Dutch. When in 1667 the Treaty of Breda gave Dutch territory on Turtle Island to the English, the Haudenosaunee became English allies. The English gave the Haudenosaunee three silver links representing Peace, Friendship, and Respect, and a wampum belt known as the Covenant Chain.

With guns obtained first from the Dutch and then from the English, the Haudenosaunee began a period of territorial expansion at the expense of First Nations allied with the French, who were based at Kebec. Though the French eventually armed their First Nations allies with guns as well, the Haudenosaunee were able to push the Ojibwe, Odawa and Potawatomi from the area south of Lake Michigan. They attacked Anishinaabe peoples along the St. Lawrence. And they pulverized the Wendat Confederacy occupying the area between Lake Ontario and Georgian Bay. Dutch, English and French representatives were supportive of these conflicts as they wished to secure the lucrative fur trade for their home countries.

A Note on Trade:

As soon as the Dutch, French, and English began trading with First Nations along the Atlantic coast of Turtle Island, European goods began to make their way to the Pacific coast along cross-continental Indigenous trade networks. Many of these were paid for with fur.

Besides fur, many other valuable commodities were traded from present-day North and South America to Europe. Corn, potatoes, tomatoes, tobacco, peanuts, squash, and cocoa were some of the items never before seen in Europe.

Meanwhile Turtle Island received new species from Europe, including wheat, rice, apples, lettuce, dandelions, turf grasses, cotton, cattle, sheep, chickens, rats, honey bees and earthworms.

The Beaver Wars:

Between 1650 and 1701, the conflict between the Haudenosaunee and the Indigenous allies of the French was intense. The Great Peace of Montreal (1701) mostly ended these “Beaver Wars”; however, Britain recruited Kanien’kehá:ka warriors to subdue the Mi’kmaq in Nova Scotia as late as 1711-1712.[4]

The Beaver Wars were not just about competition over beaver fur supply chains, but also about replacing friends and family who had succumbed to European diseases. “Mourning Wars” were low-casualty, precision raids intended to acquire captives.

By 1701, the Kanien’kehá:ka lifestyle was very much changed from its traditional mode. Most Kanien’kehá:ka, still based in what is currently New York State, were living as nuclear families in individual houses, whereas they had traditionally lived in clan-specific longhouses. Hunting and trapping for fur locally was no longer possible, because the beaver stock was so depleted. Many Kanien’kehá:ka were Christians. Many could speak English. Such changes had also occurred among Maritime First Nations who had signed “Peace and Friendship” treaties with Britain, similar in implication to the Two-Row Wampum.

Kanien’kehá:ka living in the New York area who converted to Catholicism were convinced by Jesuit priests to settle along the St. Lawrence River near present-day Cornwall and Montreal. These communities are now Akwesasne (Ontario), Kahnawake (Quebec), Kanesatake (Quebec) and Wahta (Ontario). The rest of the Mohawk Nation stayed in the Mohawk River valley, from which they had driven the Mahican. They enter Canada’s history later on.

Sadly the Beothuk, off the imperial radar, were being killed by British colonists in what is now Newfoundland, and would eventually disappear as a distinct community.

Whalers had entered Arctic waters, but not until 1850 would they set up on shore.

The English were active in Hudson Bay, where the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) had set up shop in 1670. HBC traders gradually moved inland, south and west, competing with voyageurs sent across the Great Lakes from Montreal and Quebec City.

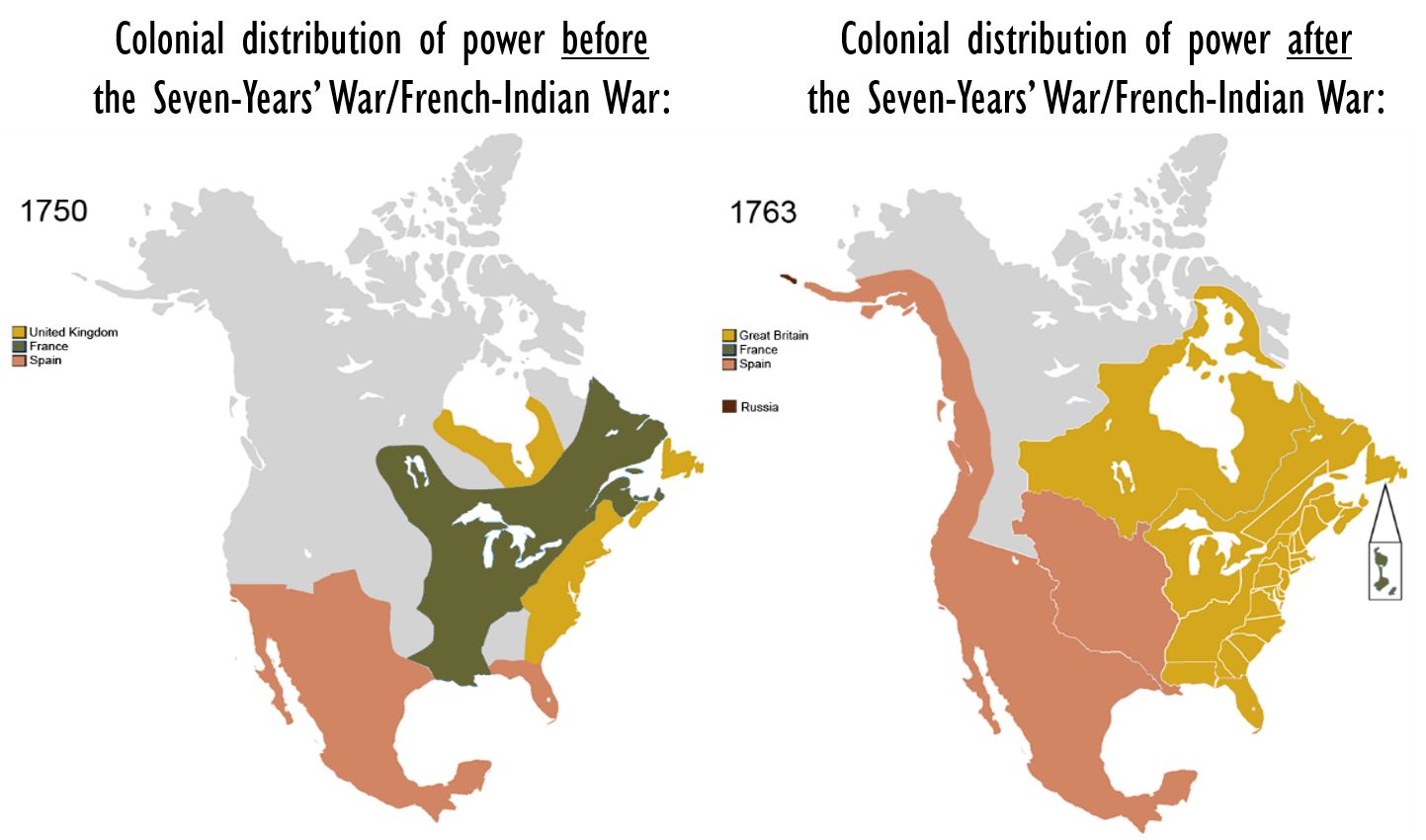

So British and French rivalry in the Fur Trade continued after the Great Peace of Montreal, coming to a head in the so-called French and Indian War (1754-1763), which corresponded to the inter-European conflict called the Seven Years’ War. Its conclusion, a decisive British victory, was a momentous event for the future of Canada and for Crown-Indigenous relations.

Consequences of the Seven-Years’ War/ French-Indian War:

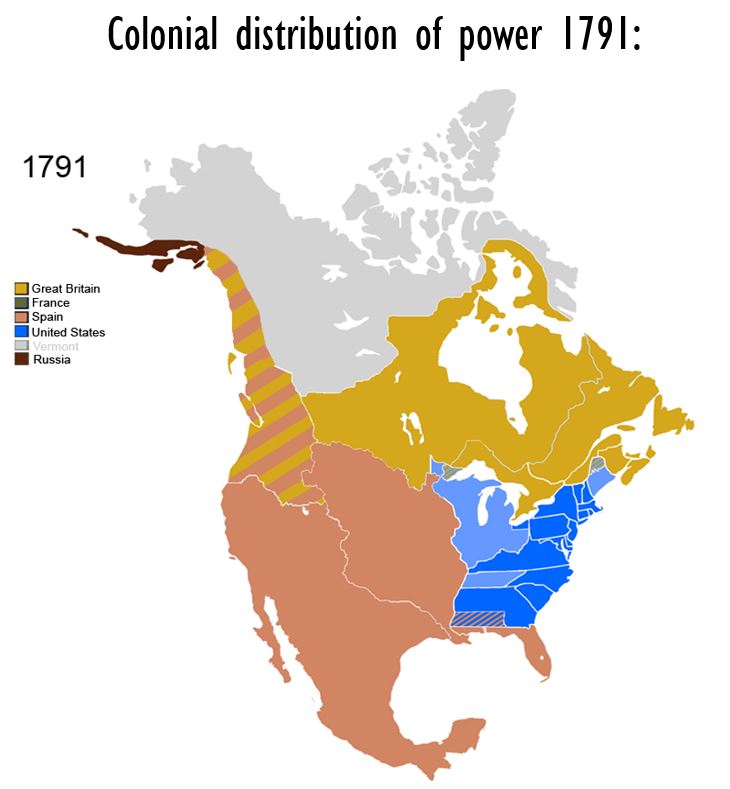

Both the Seven Years’ War and the French and Indian War ended in 1763 with Britain obtaining all of France’s colonies on Turtle Island. Some Indigenous French Allies, led by Pontiac, Chief of the Odawa, refused to accept defeat and continued to fight after 1763, extending the French and Indian War. However, France did not send reinforcements.

To better understand why Britain was able to negotiate a takeover of all French possessions on Turtle Island, consider that Britain was more heavily invested in Turtle Island than France. In 1730, 9% of British imports came from (mainland) North America compared to 5% of French imports coming from mainland North America. By 1760, 1 in 6 British people was living on Turtle Island, compared to 1 in 285 French.[5]

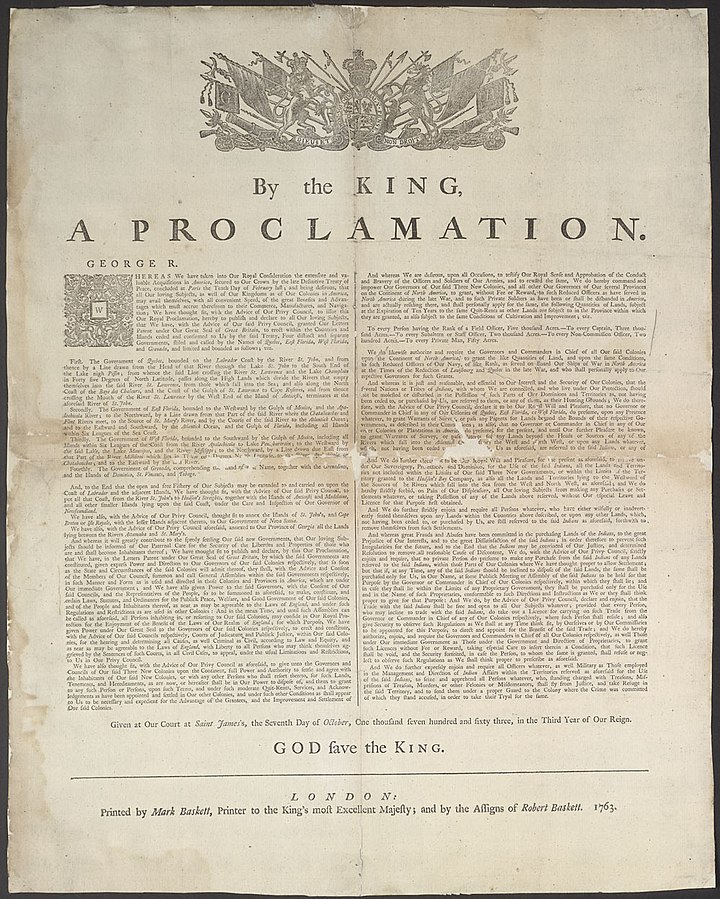

It may surprise you to learn that one of the first acts of the British government after the Seven Years’ War was to issue a Royal Proclamation (described below) concerning Turtle Island’s Indigenous people. Their interests had not escaped the attention of Britain; moreover, Indigenous leaders had visited England to protest what was happening to their traditional territories and freedoms.

In 1711, three Kanien:kehá:ka leaders and a Mahican leader had traveled to England to ask Queen Anne for military aid and a missionary. The Queen treated the visitors with great respect and authorized the building of a Royal Chapel in the Mohawk Valley. She also gave a gift of silver communion dishes which are still used today by the Mohawks of the Bay of Quinte (Tyendinaga, Ontario) and the Six Nations of the Grand River (Brantford, Ontario).

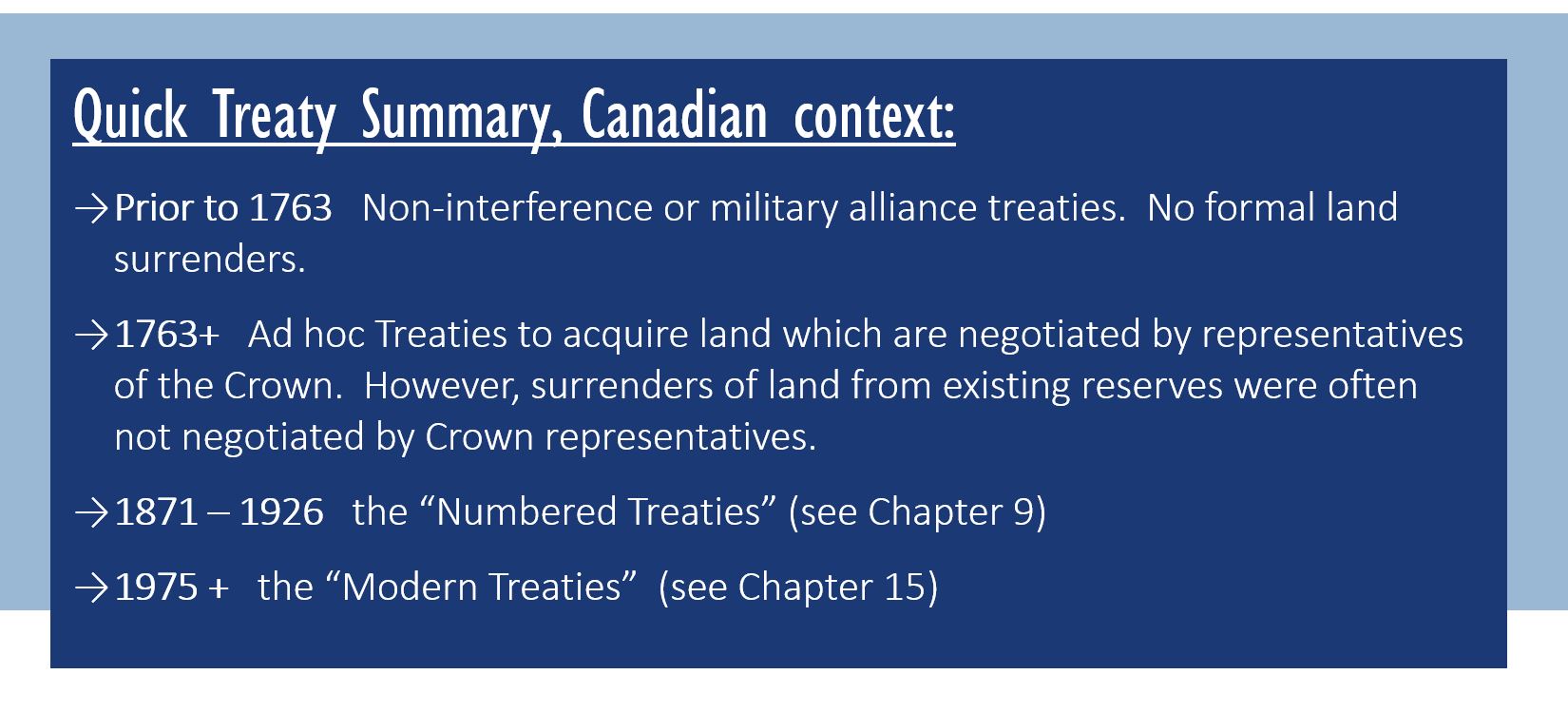

The 1763 Royal Proclamation, issued by King George the Third, instructed settlers to desist from staking out territory west of the Appalachian mountains. It asked any settlers already west of this line to move back east.

Any Indigenous land desired for settlement would now have to be purchased from the (British) Crown. The Crown would be the only party with the right to purchase lands from Indigenous Peoples:

“And We do further declare it to be Our Royal Will and Pleasure… to reserve under our Sovereignty, Protection, and Dominion, for the use of the said Indians, all the Lands and Territories not included within the Limits of Our said Three new Governments, or within the Limits of the Territory granted to the Hudson’s Bay Company, as also all the Lands and Territories lying to the Westward of the Sources of the Rivers which fall into the Sea from the West and North West as aforesaid.

And We do hereby strictly forbid, on Pain of our Displeasure, all our loving Subjects from making any Purchases or Settlements whatever, or taking Possession of any of the Lands above reserved, without our especial leave and License for that Purpose first obtained.”

“And whereas great Frauds and Abuses have been committed in purchasing Lands of the Indians, to the great Prejudice of our Interests and to the great Dissatisfaction of the said Indians: In order, therefore, to prevent such Irregularities for the future, and to the end that the Indians may be convinced of our Justice and determined Resolution to remove all reasonable Cause of Discontent, We do, with the Advice of our Privy Council strictly enjoin and require, that no private Person do presume to make any purchase from the said Indians of any Lands reserved to the said Indians, within those parts of our Colonies where We have thought proper to allow Settlement: but that, if at any Time any of the Said Indians should be inclined to dispose of the said Lands, the same shall be Purchased only for Us, in our Name, at some public Meeting or Assembly of the said Indians, to be held for that Purpose by the Governor or Commander in Chief of our Colony respectively within which they shall lie….”

This document is significant for several reasons. First, the Crown appears to have good will and a sense of responsibility toward Indigenous People. Second, it sets the precedent of the Crown reserving lands for First Nations. Third, it requires that formal treaties be made before Indigenous land can be settled. This will not always happen going forward, but it is the law.

After the Royal Proclamation, representatives of the British colonial government began to make treaties with various Indigenous groups for specific tracts of lands desired by settlers. This kind of piecemeal treaty-making went on until the late nineteenth century. Britain was able to secure land very cheaply, partly because Indigenous groups felt there was vacant land elsewhere for them to occupy. But the land base was shrinking deceptively quickly. It seems likely that many groups did not realize how soon they would be trapped on the least desirable land available, or that they had effectively surrendered forever the ability to hunt and fish in a certain areas. Loft (2019) writes:

“Canada was and continues to be in a state of conflict of interest: on one hand to protect Indians and land reserved for Indians [the terminology of the Constitution Act], while at the same time negotiating treaties and the sale of Indian land for the Crown.”

Only 11% of land in Canada is privately-owned; the rest is Crown land, which may or may not be part of a Treaty arrangment. Meanwhile, many settlers were unhappy with the message of the Royal Proclamation. This was one of the triggers of the American Revolution.

Meanwhile, many settlers were unhappy with the message of the Royal Proclamation. This was one of the triggers of the American Revolution.

The American Revolution and its Aftermath:

The American Revolution (1775-1783) resulted in Britain losing control of its colonies south of the Great Lakes. It also resulted in losses and expulsion for those Indigenous peoples who had been living in what is now the United States but who had fought for Britain. Loyalist Kanien’kehá:ka (Mohawk) and Wolastoqiyik (Maliseet) moved north to what is now Canada. The Kanien’kehá:ka were awarded lands of their choosing for resettlement.

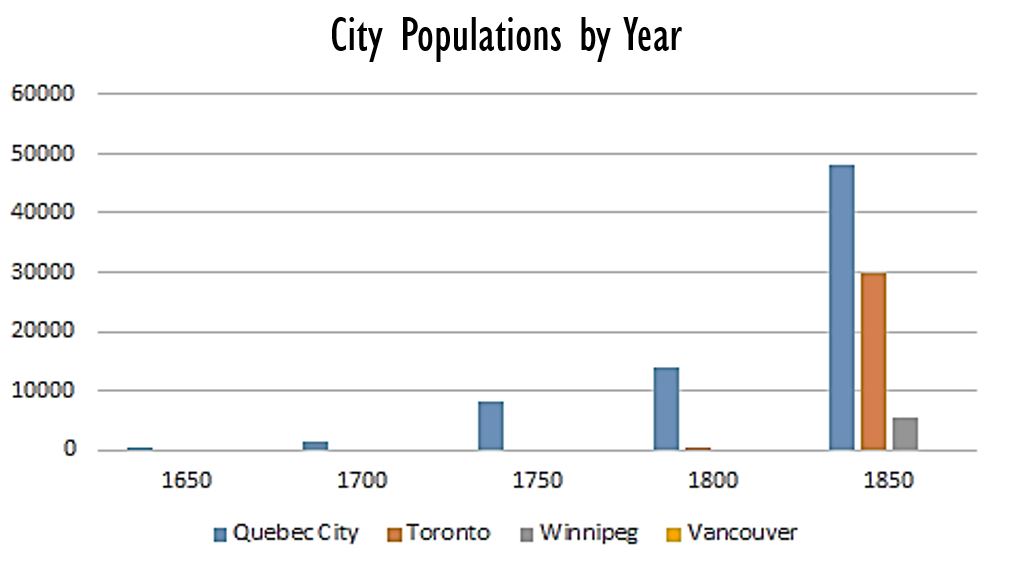

At the end of the American Revolutionary War, European territorial expansion on Turtle Island continued where it had left off, if indeed it had left off. The Americans, no longer impeded by the Royal Proclamation, continued to move West. In Canada, the Hudson’s Bay Company to the north and the voyageurs out of Montreal cultivated their Indigenous fur-trading networks in the West, but European settlement was still pretty much confined to the East. Consider that in 1800, Toronto was the settlement furthest west, with fewer than 300 people! Kingston came in at 500 people; Montreal at 8,000; Quebec City at 14,000; and Newfoundland at 14,000.[6] Acadia (Halifax), which had had more than 15,000 inhabitants in 1750, might not have had any more than that in the year 1800, due to the loss of 8000 Catholic persons deported by the British in 1755.

The Historical Atlas of Canada estimates that the settler population of “Eastern Canada” was 340,000 total in 1800. The population table above shows that, west of the Atlantic provinces, the population of Canada was largely Quebecois until after the American Revolution.[7]

The War of 1812 and its Aftermath:

The United States faced off against Britain, with its Canadian and Indigenous allies, one more time. This collection of battles, lasting almost three years, and known as the War of 1812, ended with the US- British North American border remaining more or less unchanged. Geopolitical matters between the US and Britain were wrapped up. But this had serious consequences for First Nations and Métis, as Poelzer and Coates (2015) emphasize.

First, the role of First Nations and Métis as military allies to the British became obsolete, notwithstanding their valiant service during the War of 1812, where 1,000 died in combat and a further 9,000 died of related causes.[8]

Second, the British felt that the borders were settled and it was now time to consolidate administration of Indigenous Affairs and other colonial business.

Third, the apparent geopolitical stability encouraged a tidal wave of British immigration. Between 1815-1850, eight hundred thousand people entered British North America on a base population probably half that size, so that, by 1851, with babies being born all the while, the total population was 2.4 million. Many immigrants came out of need, impelled by Highland Clearances (Scotland) or the Potato Famine (Ireland). This immigration period became known as the “Great Migration”. But for Indigenous Peoples, it was not so great.

With increasing pressure from settlers, and less interest in military assistance from First Nations, the colonial government made the protection of First Nations rights less of a priority.

Moreover, the presence of so many British, especially British women, likely changed the culture of anglophone Canada, substituting more refined Victorian manners for more relaxed, mixed-heritage traditions. In particular, the custom of having Indigenous wives and girlfriends was pushed out of polite society. First Nations and mixed-race people were marginalized and moved westward by social and economic pressures.

At this point in time the Fur Trade was no longer the most important commercial activity in the East. Lumber and farming were ascendant. Montreal was still an important depot for fur sales to Europe, but the fur was coming from what was then called “the West” – what is now central Canada.

The far West of present-day Canada was just a small part of the European fur trade, except on the Coast. Since 1770 British and Spanish ships had been visiting the Pacific Coast. Their quest: sea otter fur pelts, for sale to China. The Russians had been establishing a series of forts, colonies and trading posts north of the Haida Gwaii. Treuer (2014) describes the Russian presence as brutal, driving the Tlingit people of Sitka to rebel against forced labour and forced marriage at the Battle of Sitka (1804). Later (1867), the United States would purchase Russia’s holdings on the Pacific Coast, and that is why today the boundaries of Alaska extend part way down the west side of British Columbia. By 1812 the North West Company had a trading post near present-day Kamloops, British Columbia.

In our next chapter we will pause to take a detailed look at the fur trade.

- A virgin soil epidemic is one that takes place in a population that has never previously been exposed to that pathogen ↵

- Carlos, Ann M. & Lewis, Frank D., 2012. "Smallpox and Native American mortality: The 1780s epidemic in the Hudson Bay region," Explorations in Economic History, Elsevier, vol. 49(3), pages 277-290. ↵

- He would explore Hudson Bay the following year, and be left to die by his crew in 1611. ↵

- Wallis, W.D. and R. S. Wallis, “Culture Loss and Culture Change among the Micmac of the Canadian Maritime Provinces, 1912-1950,” in McGee (1983) p. 143”, Also MacFarlane, O., “British Indian Policy in Nova Scotia to 1760”, in McGee (1983) pp. 51-52 ↵

- Statistics from Canada: A People’s History (2006); The Canadian Encyclopedia www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca; the Historical Atlas of Canada (1987); and Le Commerce à Place Royale sous le Régime Françe;ais (1984). ↵

- Population statistics from Canada: A People’s History (2006); The Canadian Encyclopedia www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca; the Historical Atlas of Canada (1987). ↵

- This includes population increase due to births net of deaths. Concise Historical Atlas of Canada (1998), pp.3-4. ↵

- Clodfelter (2017) ↵

Ceremonial belts of woven shell beads, in purple and white. The pattern woven may symbolize a treaty.

The term "Crown" refers to the British monarch and later, after Canada became a nation rather than a British colony, to the Canadian government or to the government of one of Canada's provinces, whichever has responsibility over the matter at hand. The federal government, not the provincial governments, has responsibility for Indigenous concerns according to the Canadian Constitution.