Economies prior to the late 20th Century

Traditional Indigenous spirituality is rooted in the Land. It always seems to come back to the Land and “Mother Earth”. In Indigenous spirituality, the Land is not real estate, is not only territory, not only a source of vital resources: the Land is all of life on earth. The Land is the waters, the soil, the creatures, the winds, the stars, and what binds them together in relationship. All natural things have their own lives, feelings, choices, and purpose; like humans, they are represented and animated by spirits from the Spirit World.

Because of this, all natural things have a “sacred dimension,” in the words of Kwakwaka’wakw leader and prominent Canadian Jody Wilson-Raybould (2002, p. 104). “It is vital,” she writes, “in determining how we act in our lives, to recognize this spiritual dimension to all things, respect it, and see our connection to it.” A Cree elder has explained: “We didn’t worship the Land; we honoured it.”[1]

To honour the Land and acknowledge our connectedness to it the Kanien’kehá:ka (Mohawk) people begin and end each ceremony with the Ohén:ton Kariwatehkwen, the “Words Before All Else” which is a shout-out of greetings and thanks to all beings, to “all my relations”.  Innu writer and poet Rita Mestokosho describes the Magpie river in her people’s traditional territory as her sister. “When I am close with her, I feel like I am with my ancestors. She’s alive and I’m alive.”[2]

Innu writer and poet Rita Mestokosho describes the Magpie river in her people’s traditional territory as her sister. “When I am close with her, I feel like I am with my ancestors. She’s alive and I’m alive.”[2]

The Land is complemented by spiritual guardians overseeing the weather, the animals, water, the medicine plants, the very soil. Spirits take on physical bodies and offer themselves to one another in a cycle of living and dying. What you eat gives itself to you; its sacrifice you must honour.

The Stó:lö tell how Xa:als the Transformer turned some of their early relatives into Salmon because they were so generous; as Salmon, they could continue to give to their people.

The Stó:lö tell how Xa:als the Transformer turned some of their early relatives into Salmon because they were so generous; as Salmon, they could continue to give to their people.

Gratitude is the appropriate response. Still today, First Nations and Métis throughout Canada preserve the custom of placing a gift of tobacco on the soil when harvesting plants. Scholars Marianne and Ronald Ignace state that xyemstém, being respectful, is at the core of Secwépemc beliefs about humanity’s relationship with the Land. People, including ancestors, animals, plants, land, sky, and waters are “reciprocally accountable.”

Vancouver community Elder and Anglican priest Vivian Seegers spent her early childhood years in the bush near Uranium City, Saskatchewan during the 1970s. One of the first instructions from her father was to walk without flattening plants or breaking twigs. He told her she was in the animals’ house, and she shouldn’t make it untidy. She also recalls her mother and aunts competing as to which one of them would leave her family’s campsite most pristine. Each of them collected twigs, pinecones and pebbles to scatter over the campsite upon departure. Since animal spirits take flesh and sacrifice themselves to people’s needs, hunters must show respect and gratitude. Beardy and Coutts (2017, p. 123) record that among the Cree, it is wrong to light a fire at night, when geese might be irresistibly attracted. It is unfair to hunt geese when the air is calm and they cannot easily take off into the wind. Also, hunting in the dark is wrong because wounded or dead animals might not be found, thus their sacrifice would be wasted.

Since animal spirits take flesh and sacrifice themselves to people’s needs, hunters must show respect and gratitude. Beardy and Coutts (2017, p. 123) record that among the Cree, it is wrong to light a fire at night, when geese might be irresistibly attracted. It is unfair to hunt geese when the air is calm and they cannot easily take off into the wind. Also, hunting in the dark is wrong because wounded or dead animals might not be found, thus their sacrifice would be wasted.

Recording the teachings of the Cree living on the western shores of James Bay, Hans Carlson (2008) writes:

“The real hunt happened long before the hunter picked up his snowshoes to go to the bush. It happened when he communicated with the animals and asked for their help in feeding his family; their answer would be based on their knowledge of whether he had been grateful for what they had given in the past. Going out and killing an animal was the consummation of a covenant that had already been made.[3] This is the reason a Cree would stoically go without food for days, and would not rely on large stores of dried food. His or her patient abstinence was a token of faith in the spirit world.”

After the hunt, meat must be shared according to norms of generosity. Stingy people should not expect nature to be generous with them.[4] The remaining carcass is not discarded with indifference. As a sign of respect and thanks, fish remains are thrown back into the water, speeding the fish spirit back to its home; animal remains may be decorated or wrapped in cloth, then placed on racks or hung in trees. Another way of showing thanks for a very successful hunt is to feast and share food. Consider that storing food could be insulting to the spirit world. “Too large a store implies a loss of hope for the future of the human/other-than-human relationship, thereby jeopardizing the hunter’s luck.”[5]

Consider that storing food could be insulting to the spirit world. “Too large a store implies a loss of hope for the future of the human/other-than-human relationship, thereby jeopardizing the hunter’s luck.”[5]

We see that these hunting norms fit well with the material realities faced by hunters: a possible scarcity of prey; difficulty storing or transporting food; and needing to keep scavengers away from campsites. But instead of concluding that material realities shaped spiritual beliefs and practices, traditional Indigenous teachers would understand both the material and the spiritual to be manifestations of the same underlying reality.

In keeping with the non self-centered view of nature in Indigenous tradition, the rights to the things of nature are not considered personal. This is implicit in the Kanyen’kehá:ka language, where you cannot say “my dog” in the same way as you say “my house”. The creatures found in the natural world do not exist for your pleasure.

The spirit world can be a dangerous world. There is hostility from offended spirits. There can be people who want or who are merely suspected of wanting to use spiritual power to harm others.[6] So communities had and some still have their shamans who will enter trances in order to visit the spirit world and intervene on behalf of the living.

Traditional Values

Generosity and selfless action are values strongly encouraged in traditional Indigenous culture. For example, Carter (1993) describes the Worthy Young Men society of the Nêhiyawak, membership in which was earned by daring exploits. Once worthy young men had acquired enough possessions, they would be invited to join the Warrior Society or Okihcitaw, which, when translated, refers more to honourable actions than to fighting. Warriors were expected to give up their possessions for the community and to provide for the poor and for visitors.

Among the Inuit “When a man killed a seal it was taken to his igloo, where his wife butchered it, giving different portions to the wives of the other hunters according to their specific relationship. The hunter kept little for himself but would share in all his partners’ future kills.” (Macmillan and Yellowhorn, 2004).

Ann Carlos and Frank Lewis (2010) describe the generosity prevalent among First Nations of the Hudson Bay and James Bay hinterlands in the eighteenth century. Generosity means that you will feed and house visitors. From an economic point of view, this norm provides a kind of insurance. When you are in need, someone will help you, perhaps even the same person whom you have helped.

From a spiritual point of view, you take your turn sacrificing for another being who has no less a right to exist than yourself. Generosity may be implicit in the fact that several Indigenous languages, such as Anishinaabemowin (Ojibwe), Kanyen’kéha (Mohawk), and Nêhiyawêwin (Cree), have no word for “please”. How would you interpret this?

Norms of generosity, and of reciprocity for generosity, in some cases made Indigenous societies vulnerable to exploitation by European newcomers.

“They say the Indians know nothing, and own nothing…This is how our guests have treated us, the brothers we received hospitably in our house.” (Chiefs of the Secwépemc (Shuswap), Okanagan, and Couteau Tribes, 1910)

In traditional and present-day Indigenous communities, relatives are not turned out onto the street, and children are informally adopted as needed.

Good Samaritan Principle:

Related to generosity is what Carlos and Lewis call the Good Samaritan Principle. This is the principle that people who are hungry are allowed to enter your territory to hunt for food. This makes economic sense, because large game animals wander (moose, elk) or migrate (caribou, bison) over vast distances. Additionally, a wounded animal can cross territorial boundaries as it flees the hunter. You cannot keep wild game animals on your own territory.

Carlos and Lewis assert that the Good Samaritan principle allows neighboring First Nations to view the game animals as a shared resource, one that is a collective responsibility, rather than something for which to compete. On the other hand, knowing that you can cross boundaries to find food might incentivize you to take less care in your own domain. What do you think about this?

It has to be noted, however, that there were at times fierce rivalries and terrible hostilities among Indigenous peoples, between Cree and Inuit, for example. The Good Samaritan Principle had its limits. Many First Nations glorified war and raiding, courage, deceit, and the ability to undergo deprivation.

In his book, “The World Until Yesterday (2012)”, geographer Jared Diamond asserts that tribal societies typically engage in more warfare than state societies:

“…the mass of archaeological evidence and oral accounts of war before European contact…makes it far-fetched to maintain that people were traditionally peaceful until those evil Europeans arrived and messed things up. There can be no doubt that European contacts or other forms of state government in the long run almost always end or reduce warfare, because all state governments don’t want wars disrupting the administration of their territory. [But] Studies of ethnographically observed cases make clear that, in the short run, the initiation of European contact may either increase or decrease fighting for reasons that include European-introduced weaponry, diseases, trade opportunities, and increases or decreases in the food supply.”

Other reasons that a smaller, less economically complex population might be more inclined to warfare include the facts that the group has fewer material goods to lose from warfare, is more desperate for food, women, and children at times, and has less capacity to organize peacekeeping or to restrain rogues.

According to Diamond, traditional tribal warfare from around the world and throughout human history consists mostly of raiding, motivated by retaliation, procurement of women, children, slaves, and livestock, and access to territory for hunting and trapping. This is consistent with Indigenous oral history.[7] Indigenous oral history also attests to peacemaking through diplomatic ventures, treaty-making, intermarriage, and adoption.[8]

Trading and Profit:

We have earlier noted the existence of extensive Indigenous trade networks. Some individuals and some nations specialized in trade, acting as middlemen and looking for profit. For example, the Chinook people of present-day Washington State were so involved in trade that a version of their language became the language of commerce along the Pacific Coast and along the eulachon “grease trail”. Describing pre-contact culture among the Secwépemc (Shuswap), Marianne and Ronald Ignace explain that, “whereas the exchange protocols among [relatives] were based on the values of generosity, reciprocity and mutual support exemplified as knucwentwécw (helping one another)…, the protocols of eykemînem (trade something in payment for purchases) and eyentwécw (pay one another) involved barter or profit-seeking by individuals not closely related to the trader.” Profit could also be earned on the sale of fabricated items to people within the tribe.[9]

Jody Wilson-Raybould (2022, p. 219) writes, “Within this complex network [of individual, community, and tribal interconnections and interdependence], there was what we would characterize today as commercial and trade relations, but these were based on communal and collective understandings of prosperity and wealth rather than ideas of individual ownership.”

Property Rights

Generally speaking, clothing, tools, weapons, dogs, horses, temporary housing, and domestic goods belonged to individuals. This did not mean that they thought of these things, these animals as personal property in the western sense. But an individual had the right to not have these things taken away from them. An individual’s right to the meat or roots or produce they had obtained through their own labour was moderated by the tradition and expectation of sharing with others. Longer-lasting houses, such as those built on the West Coast or in Iroquoian villages, were communally owned.

Similarly, the territory of a band was collectively owned and managed, with the exception of high-maintenance fishing sites on the Pacific Coast and in the Plateau east of the Rocky Mountains. Boundaries with other Nations were well understood.

Who Were the Chiefs?

Public leaders were men[10] who had earned the community’s respect for skill in battle, trade, or hunting. Among the Nêhiyawak, a chief had to be wealthy and generous. “He freely gave his possessions to the needy, his wife distributed the choicest cuts of meat after a successful hunt to those short of food, and his household took in sons of the less affluent and orphans and treated them as members of the family. On occasions for ceremonial gift-giving and at a feast the chief was expected to donate the largest share… To ease tensions, he often had to bestow a gift upon the aggrieved person or replace from his own possessions an item an individual believed had been stolen.” (Carter (1990) p. 30)

Easing tensions in a small community is essential, since the breaking up of the community could imperil its survival. Consistent with the need to retain and empower each community member to take his or her place in society, traditional Indigenous legal systems emphasize restorative justice. Restorative justice is about reconciliation and rehabilitation rather than punishment.

Today, restorative justice is worked out using a “healing circle” in which offenders, victims, family members, community members and elders share their feelings and thoughts, coming to an agreement as to how the harmful behaviour should be remedied.

Consensus Decision-Making:

While one or more chiefs led each tribe within a nation, the authority of chiefs was not absolute, nor did chiefdom automatically descend to a man’s sons. Instead, chiefs depended for their authority on the community’s approval. Via a process of consensus decision-making, chiefs were to appear to “rubber-stamp” the community council’s decision.[11]

Consensus decision-making is a common feature of Indigenous organizations. This is illustrated today by the use of talking circles, where an entire group is seated in a circle. The circle represents equality and inclusion. As a feather or other sacred object is passed around the circle, the person holding the object has the opportunity to speak without interruption.

Consensus decision-making is also a feature of the Great Law of Peace[12], that is, the guiding principles of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy. According to the Great Law of Peace, 50 chiefs from the participating Nations meet around a central fire maintained by the Onondaga. Each Council session begins with the Ohén:ton Kariwatéhkwen referenced earlier, and then discussions begin. Decisions are made in a gradual process to maximize the possibility of reaching consensus. First the Mohawk agree among themselves on the issue at hand; they then come to agreement with the Seneca. Once the Mohawk and Seneca agree, the Cayuga and Oneida come to an agreement between themselves. If the Cayuga-Oneida decision conflicts with the Mohawk-Seneca decision, then the Onondaga leaders make the tie-breaking vote; however, the Mohawk, who were the first to adopt the Great Law, have veto power.

Indigenous Values Today

Having surveyed broad aspects of traditional Indigenous culture, we may have a sense that Indigenous communities today will be oriented somewhat differently than mainstream western ones. Much of the community spirit, ethic of generosity, and respect for nature continues.

At this point in our text we have not yet discussed the many experiences of Indigenous peoples after contact. Suffice it to say that much has been suffered. There has also been significant assimilation, by intermarriage, by cultural influence, and by government design. Indigenous populations have been split, scattered, joined, and forced together by disease, war, intermarriage and adoption, environmental degradation, land expropriation, and government-mandated relocations.

Yet much of the Indigenous cultural heritage remains. The Citizen Potawatomi Nation in Oklahoma, for example, continues to celebrate the minidewak, a ceremonial giveaway reminiscent of the potlatch. Robin Wall Kimmerer writes:

Often, if the giveaway is small and personal, every gift will be handmade. Sometimes a whole community might work all year long to fashion the presents for guests they do not even know. For a big intertribal gathering with hundreds of people, the blanket is likely to be a blue plastic tarp strewn with gleanings from the discount bins at Walmart. No matter what the gift is…the sentiment is the same. The ceremonial giveaway is an echo of our oldest teachings.[13].

Many Indigenous people, from the various First Nations, Métis, and Inuit communities, carry on these teachings and set goals for their communities which include more than just income and consumption.

For this the Medicine Wheel is a useful model. The Medicine wheel is a two-dimensional depiction of concentric circles radiating along and between the four directions. Progress is made by moving outward in all four directions at the same time. To judge progress, a 360 degree view of the situation is required.

Medicine wheels appear to originate in the cultures of the First Nations of the Plains. In Canada these arrays of stones laid on the ground are found across the northwestern Plains, especially Alberta. Some were built as recently as the twentieth century by the Blackfoot, who describe them as memorials to warrior chiefs. The inner circle represents the tipi where the dead chief was laid. The spokes radiating outward indicate his influence and accomplishments. It may be the case that some wheels were used astronomically, or religiously – for example to depict a Sun Dance.

A similar wideness of perspective exists in the concept of Etuaptmumk: “Two-Eyed Seeing” which has been described by Mi’kmaw Elder Albert Marshall.[14] Two-eyed seeing means that more than one point of view must be taken, for example the native and non-native points of view.

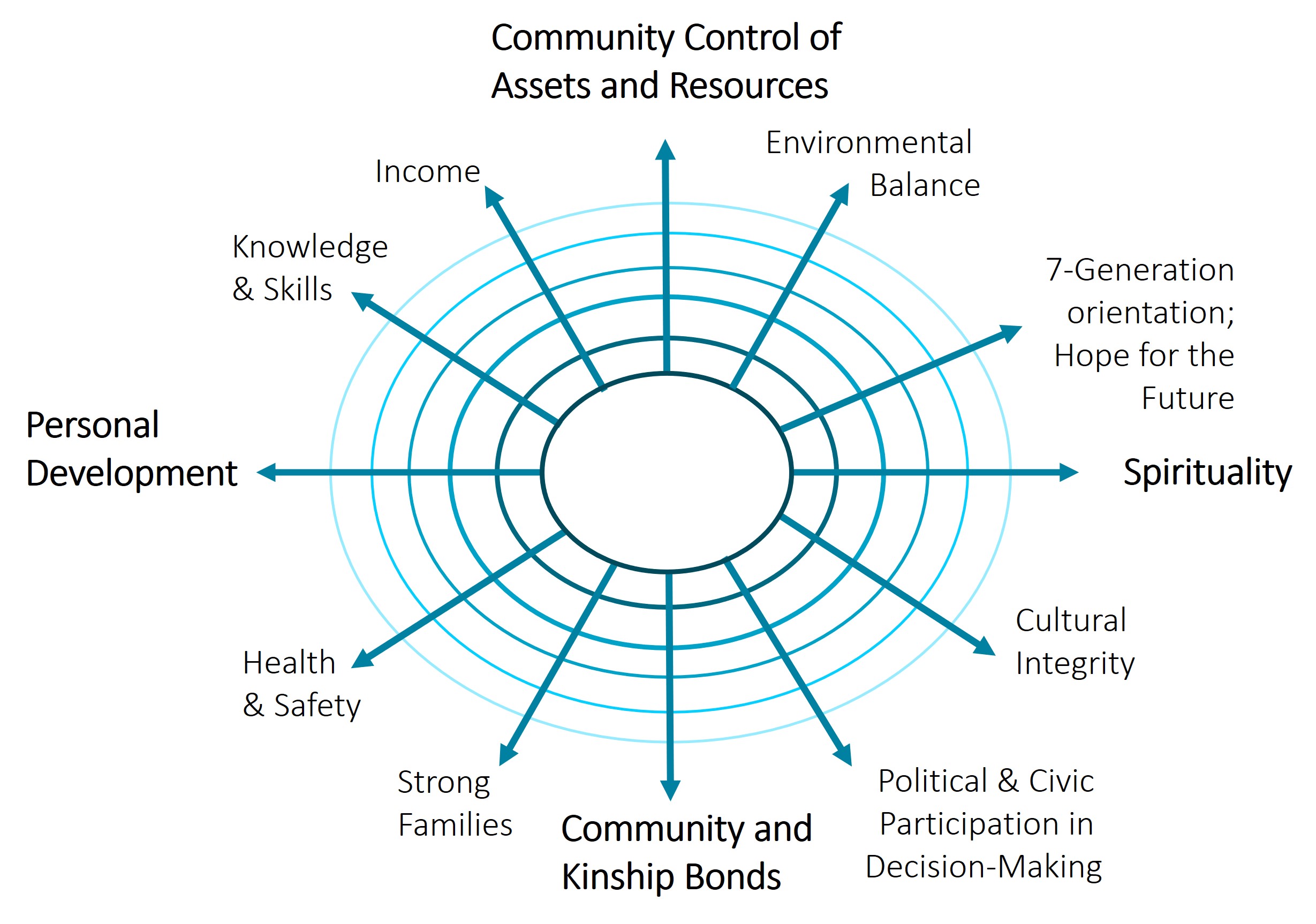

Medicine wheel diagrams are used today to represent the worldview indigenous to Turtle Island. They are often divided into four colours, symbolizing the Four Directions, four stages of life, four seasons, four elements, Body-Mind-Heart-Soul, and more. Songs may be sung four times, once for each direction. Here is an application of the medicine wheel to community goals, based on a wheel in Salway Black (1994) reported in Wuttunee (2004).

As portrayed in this medicine wheel, a community’s development goals are met by promoting individual accomplishment (west), community bonds (south), spirituality (east), and control of assets and resources (north), each of which is a ray moving from the centre of the wheel. When individuals are empowered and community ties are strong, there will be healthy families and safe neighbourhoods, as shown by a southwesterly ray. When community ties are strong, and spirituality is understood and practiced, there will be interest in and inspiration in decision making (southeast), and the culture will be preserved. When spirituality is strong, and there is control over resources, resources will be used in a responsible way to promote environmental health and sustainability (northeast): with faith and hope, individuals will not sell out now but invest for “7 generations”[15] into the future. When the community has control over resources, and individuals are empowered, skills and income will result (northwest).

The medicine wheel is about integrating multiple goals at the same time, rather than securing income first, subsequently protecting the environment, then later investing in community, which is more typical of mainstream priorities. Canadian federal and provincial elections are often focused on jobs, economic growth, and tax reduction to the exclusion of much else. And many models of economics used in research do not even consider environmental, cultural, or family conditions. Economic development reporting focuses on gross domestic product (GDP), a measure of the value of all the final goods and services produced within Canada’s borders during a year.[/footnote] or GDP per person.

Economists have developed measurements such as Green Net Domestic Product and Adjusted Net Savings/Genuine Savings, which adjust GDP and Investment, respectively, for changes in natural and environmental capital. But these measures are not commonly used.

Alternative Measures of Economic Development

We previously discussed the Community Well-Being Index which is computed every five years by the federal ministry responsible for Indigenous Services. The Community Well-Being Index registers income, housing, education, and employment status. An alternative is the Human Development Index, developed by the United Nations. It is based on life expectancy, education, and income.

A more comprehensive index is the Federation of Canadian Municipalities’ Quality of Life Index. This index is much more detailed, including statistics on voting, the natural environment, and the incidence of crime. A few of its indicators, like newspaper circulation and public transit costs, are more appropriate for cities than for smaller Indigenous communities, but it could be adapted and customized for smaller Indigenous communities. Some of its indicators are very relevant to Indigenous communities, particularly vacancy rates, water consumption, and suicides.

An index of wellbeing for an Indigenous community should include indicators for all the community’s highest priorities, possibly such things as the number of speakers of the community’s traditional language, the use of wild foods, the degree of income inequality, the number of Indigenous-owned businesses, the number of people living with diabetes, and the number of community service organizations.

Such indexes have been developed for urban settings as well as reserve settings. For a detailed list and description of various indices, see Bruce et al (2013).

All indexes are weighted averages formed by choosing different indicators, normalizing each of them to a common scale (for example to a value between 1 and 10), and then multiplying each indicator by a fraction between 0 and 1, called the “weight”. The weights must add up to 1.

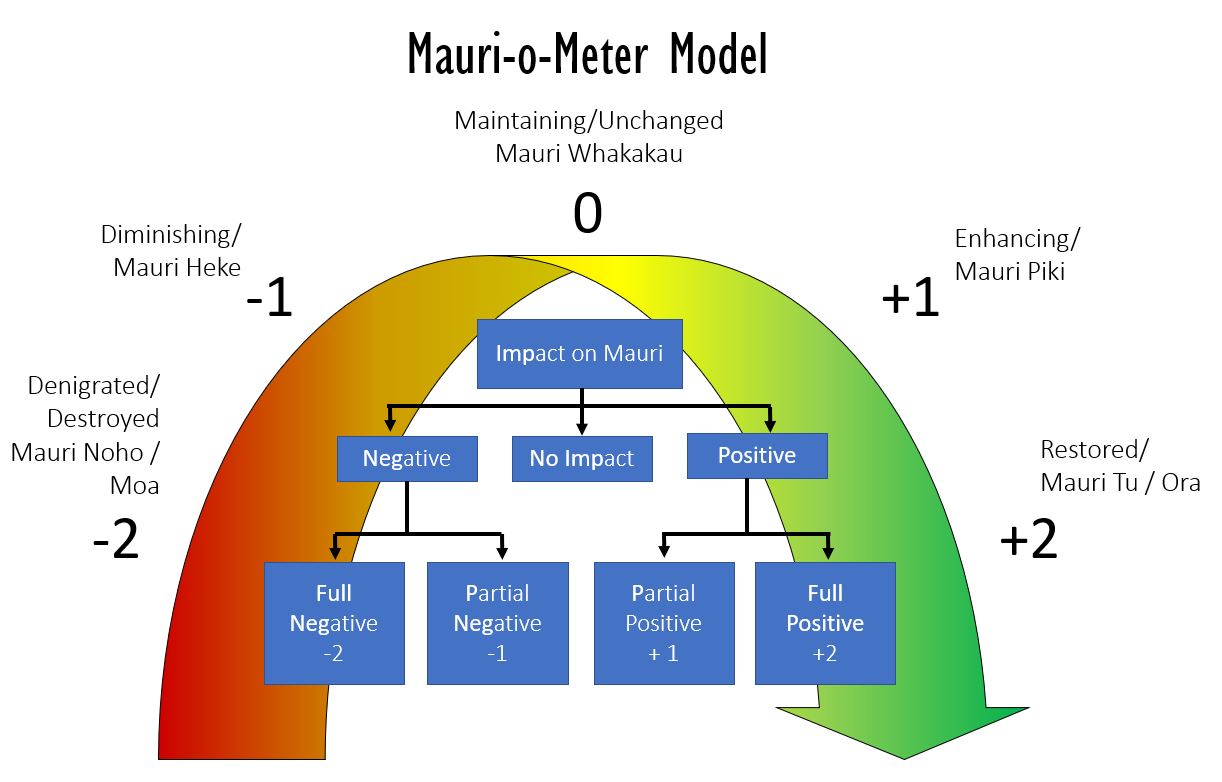

The Mauri-O-Meter is a tool developed by Dr. Kēpa Morgan to help users evaluate projects from the holistic point of view that is the cultural heritage of the Maori, the Indigenous People of mainland New Zealand. The mauriometer generates an index to give a project an overall rating. Users choose indicators and then measure those indicators on a scale of -2 to +2. The software weights each indicator equally to produce an overall project rating, but users can change the weighting scheme.

Wilson-Raybould writes

“…at the core of my Kwakwaka-wakw worldview is the belief that all things are in their greatest state of well-being when there is balance. This includes balance between humans and the natural world, between genders, between groups of peoples, within a family or community, or in how we live and organize our lives. Balance is viewed as the proper state of things, where conditions of harmony and justice flourish, while imbalance is what gives rise to conflict, contention, and harm….A society imblanced…is like a bird with an injured wing. It cannot fly, its purpose and potential cannot be met, and all are held back.”[16]

Any measure of Indigenous well-being should be holistic. The following quotations illustrate the holistic way of thinking:

“I am not against development or all construction over economic activity and all the rest. That is not the position of the Crees of northern Quebec. We know that some development is necessary, and we understand that there is value in progress and advancement. We are not attempting to avoid high technology, machinery, electricity, and other signs of progress. But I must ask if every project, if every new structure, every new highway, if every dam is really ‘development’.” ~ Grand Chief Matthew Coon Come, 1992

“And it’s so easy when you are a businessman. Cultural shock does not show on your statement of profit and loss. It’s so plain when you are a politician – you know what the voters want, you have your ears to the grass-roots and hear the voices from business, unions, political alliances.

But you do not hear the voices talking in a strange tongue in ways you have never really considered. It’s cut and dried when you are an economist – you can put it all down in black and white, prove just how beneficial it is and will be.

An abstraction such as “cultural genocide” belongs in the university – an academic question. As a priest, you are bound to see some things from a different angle…what is the real cost of the kilowatt of electric power; of a carload of newsprint or a board-foot of lumber; of a ton of copper-ore; ….not only what it will do for people, but also what it does to people.

You wonder, and you are glad when you hear people asking such questions as “Is it worth it? What’s more important, people or things?” for these should be asked.

And you wonder, too, why [western] society, which has created the bulldozer, so often has to act like one: why it all has to be so loud, overpowering, callous, heavy-handed, cold and impersonal…

You wonder if it all could not be humanized a bit, our politics, our business, our economics, if we couldn’t be a little more gentle – gentle as the people we meet in that land?”

~ Hugo Muller, a former Hudson’s Bay Company worker and later, an Anglican priest living in Northern Quebec, 1975.

An Indigenous understanding of development is multidimensional – empowering people, strengthening families, building community, honouring the Land, remembering traditions.

This is something to keep in mind as we study the economics of Indigenous communities past and present.

The Gift of Silence:

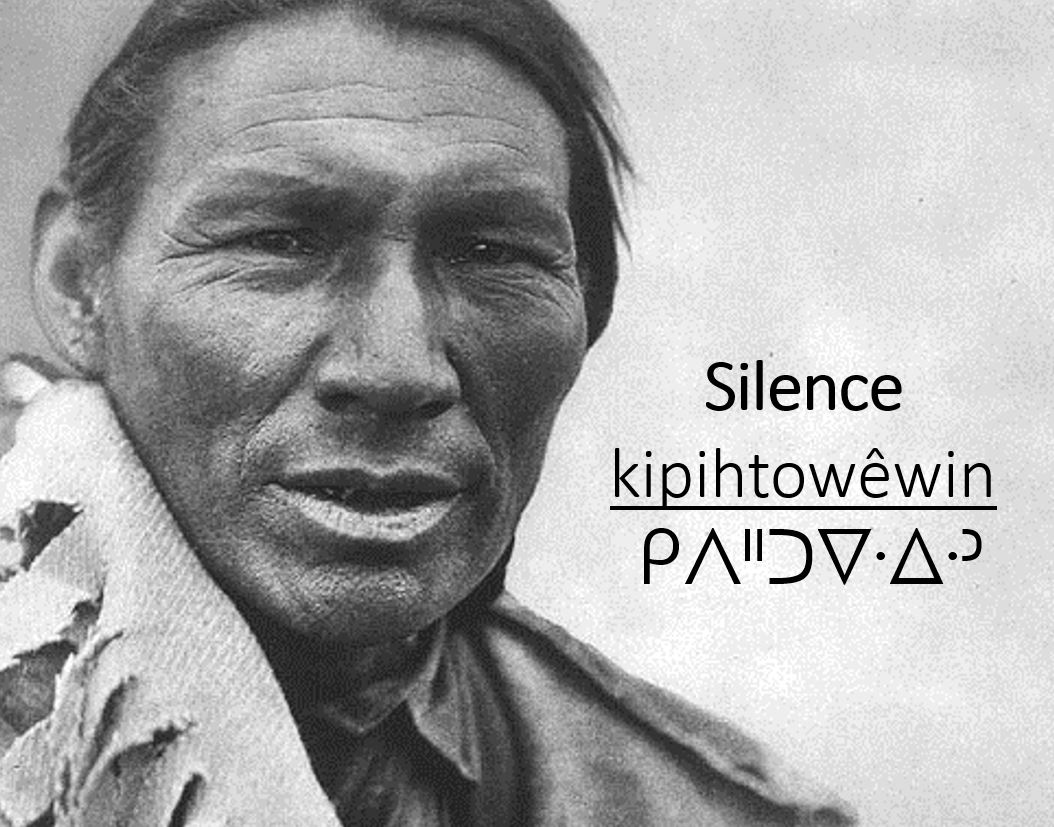

Indigenous communication styles are often different from what is mainstream in non-Indigenous culture. Often, Indigenous people are uncomfortable with self-promotion; with telling others what to do; with saying “no”; with explicitly explaining the moral of a story; and with continuous conversation.

“A blabbering hunter is a hungry hunter”[17] could be part of the explanation for a style of conversation that is quieter and more reserved. Another way that silence and discretion fit traditional Indigenous living is that, when people live and work closely together, it is necessary to respect personal boundaries to avoid misunderstandings, resentments, and conflict. Silence also makes room for the focused observation and listening that is vital to relationship with the Land.

Making Economics align with Indigenous values

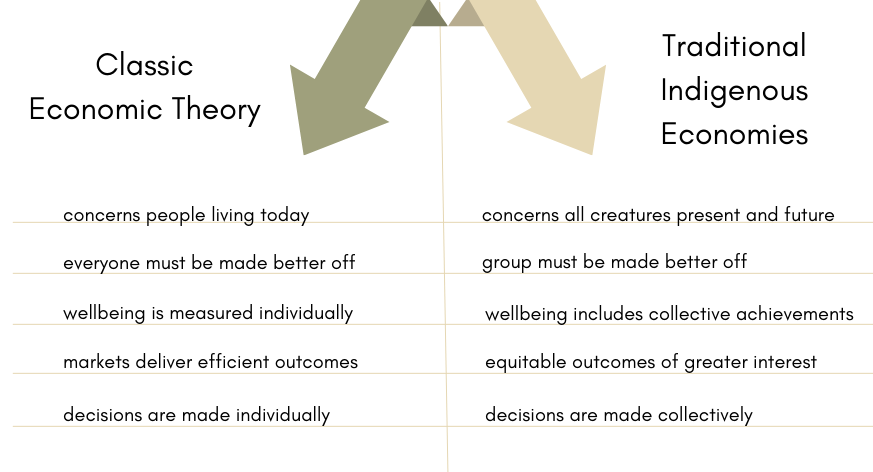

Classic and modern Economics clash with Indigenous values. Although Economics is socially-minded, and approves policies that increase social welfare (defined as the sum of everyone’s utility,) it is fundamentally more anthropocentric, present day-oriented, and individualistic, as shown in the Table below.

In Economics, everyone must be made better off by a new project or policy: those who gain must compensate those who lose. That is the theory, but in reality, compensation is incomplete.

Global warming, social harms as a result of rising income inequality, and other problems alert us to the desirability of incorporating Indigenous values into economic theory and policy.

The author attempted, as a young student of economics, to generate equitable outcomes from market-based processes. It did not seem possible except by giving everyone the income to participate equally in the market. Market-based processes are not the only way of organizing economic activity, however. Markets have been admired for their efficiency, and they have marvelously raised the material standard of living for almost everyone. But markets do not function for wildlife and many other marvels supplied by wilderness, sky, and sea, nor do they function for future generations.

If we model the everyday decisions people make in a richer way, we may be able to generate results that do not require markets. The model of Mukesh Eswaran (2023) is a step in this direction.

In his paper, “The Wrongs of Property Rights: the erosion of Indigenous peoples’ identity and its health consequences”, Esrawan provides a microeconomic model that embodies collective ideals and illustrates the possible negative consequences of privatizing Indigenous land.

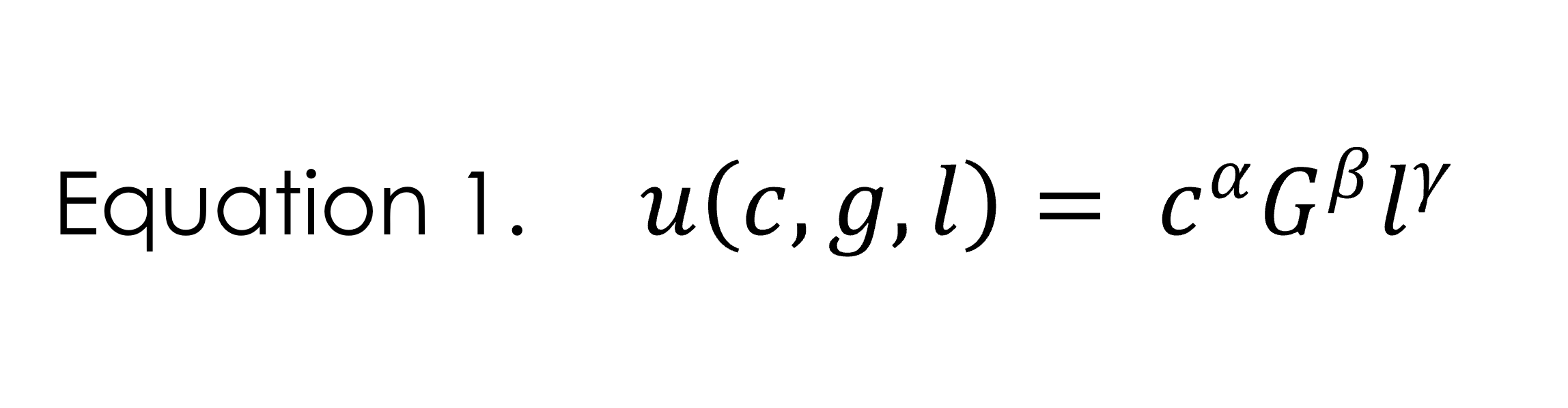

Eswaran begins with an egoistic model of utility maximization, where a community member’s utility depends only on the member’s own consumption of food (c), leisure (𝑙), and enjoyment of a group cultural activity G. Equation 1 proposes the following utility function for an individual band member:

Each of the exponents is a fraction, in keeping with diminishing marginal returns. Diminishing marginal returns means that the more of something you have, the higher your utility, yet each additional unit of the good or activity provides less of a boost to utility than the previous unit did.

Each community member has a limited amount of time and has to decide how much time to put into food production so as to achieve c, how much time g to spend in cultural activities, and how much leisure 𝑙 to enjoy. The level of group cultural activity is the sum of all the community members’ individual contributions of time gi.

Food is produced using time and land, either collectively owned land or privately owned land (where each individual has an equal share of the community’s land.) If the land is used collectively, individuals receive an equal share of the output they have worked together to achieve.

Solving for the individual’s optimal choice of time, Eswaran assumes that there is no strategizing about other’s actions. Each person behaves the same way and assumes their own choice will not affect others’ choices.

The result is predictable: the less someone cares about culture (signified by the level of β), the more time they spend on food production and leisure instead of cultural activity.

Other things being equal, the less the impact of a particular good or activity on utility, the less time will be spent producing that good or performing that activity, and the more time will be spent producing substitute goods and doing other activities.

We also find that, the larger is the community, the less the time spent on (communal) food production and the group cultural activity, and the more the time spent on leisure.

Other things being equal, the larger the community, the more shirking that occurs.

→ Can you intuit why this is the case? Have you ever decided whether or not to come to class based on the size of the class?

Collective activity typically suffers from inefficiency due individuals shirking and hoping to free-ride on others’ efforts. This is the classic public goods problem.

In Eswaran’s model, individuals enjoy the collective G, formed by the sum of each individual’s choice of how much time to spend in cultural activities. Individuals who shirk reduce G for themselves and everyone else, by the full amount they shirked. They have more of an incentive to shirk in food production, where they receive an equal share of collective output. Shirking results only in a partial loss in that case.

Working out Eswaran’s model, individuals shirk in cultural activity and especially in collective food production. The larger the size of the band, the more shirking will occur.

Though shirking takes place in collective food production, Eswaran shows that privatizing food production will not necessarily solve the problem.

When there are two public goods – in this case food production and cultural activities – privatizing one may make the shirking problem worse for the other activity. The Theory of the Second Best[18] says that when there is one distortion in an economy, social welfare may increase when you add another distortion. For example, a Pigouvian tax on a polluting activity can move the economy toward the socially optimal level of that activity, correcting the negative externality inherent in the polluting activity.

When land is divided up between individual community members, who then produce food on an individual basis on their private land allocation, community members spend more time on food production, which ceteris paribus increases their utility. However, they consequently spend less time on group cultural activities and less time on leisure. When the utility function has a high value of “β”, indicating that group cultural activities are important to community members, individuals will achieve less utility when food production is privatized than when it is a collective enterprise.

Privatized food production leads to more food production effort and results, but less leisure and less group cultural activity. If culture is important to a person’s utility, privatized food production leads to less utility overall.

The Dawes Act of 1887 began a process of privatizing reserve land in the United States. One privatization effort in Minnesota actually resulted in less agricultural output than before, according to Akee (2020). Land ownership and home ownership decreased over time, perhaps because of market disadvantages.

Similarly, Aragòn and Kessler (2020) and Pendakur and Pendakur (2021) show that in 2016, the extent of private property rights was not positively correlated with the average income of Indigenous communities. These results are discussed in Chapters 16 and 24.

This is not what Eswaran is predicting, however. Eswaran is not predicting that privatization of land will result in less food production and less income. Eswaran is predicting that privatization of land will result in more food but less utility.

This result becomes even stronger when individual band members are not egoistic but care about others’ welfare too. Let’s examine that case.

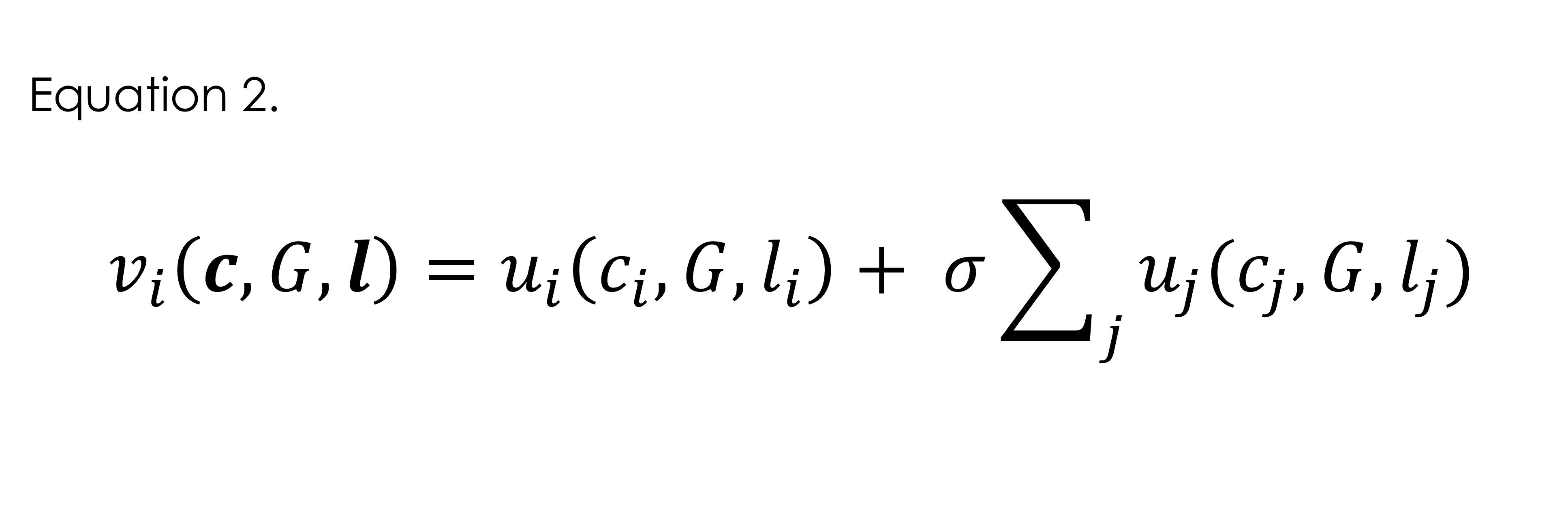

Since individuals are still making decisions for themselves, we use individual utility functions, but this time those individual utility functions depend not only on the individual’s own c and 𝑙 but also on the c and 𝑙 enjoyed by others, and on how many other people are enjoying G.

Individual i’s new utility function, vi, is the egoistic utility function from Equation 1 attached to an altruistic component weighted by parameter σ. The altruistic component is the sum of everyone else’s utility functions.

Eswaran calls σ the “belongingness” parameter.

The bold c and 𝑙 are vectors containing the c and 𝑙 of everyone in the community.

Eswaran shows that individuals will achieve higher utility the higher their sense of belonging, σ. Even the egoistic portion of an individual’s utility will be higher than before because all individuals are shirking less. Thus G, and C if food production is collective, will both be higher than without concern for others.

The less egoistic a person is, the higher the level of utility which can be achieved in a public goods setting, even if we focus only on the egoistic component of utility.

We can always imagine a person’s preferences changing so as to result in higher utility; for example, we can imagine a person ceasing to care about culture because it is technically easier to derive utility from consumption of food. That’s why it’s important that we consider what happens to the egoistic portion of utility, equation 1, when utility becomes more than just egoistic as per equation 2. The answer is that egoistic utility increases: the individual benefits from not shirking (given that everyone else behaves identically), and the individual will only stop shirking when they are non-egoistic.

This magnificent result, so sorely lacking in the conventional economics literature, clearly applies to all societies to some degree. Studying the economics of Indigenous communities is shedding light on general economic principles.

Eswaran goes on to show that as the sense of belonging (σ) increases, the egoistic utility achieved under collective food production dominates the egoistic utility achieved under privatized food production, even when cultural activities are not very important to utility (i.e. low levels of “β”).

If belongingness is sufficiently high, collective food production will provide higher overall utility than private food production, even if culture is relative unimportant to utility.

Although utility overall improves with a sense of belonging, the (theoretical) amount of food produced would still be higher under private property than under collective food production. Writes Eswaran, “The reason is that the private property equilibrium is not the correct benchmark of efficiency; in that equilibrium, there is overproduction.”

This sounds like a pretty good description of western consumerism. How much of the vast amount spent on consumption is compensating for a lack of a sense of belonging, or for reduced group cultural activities?

Let’s explain this “overproduction” some more.

A social planner would like to maximize the total utility or “social welfare” of the entire community. An egalitarian approach would be to weigh each person’s utility equally by maximizing the sum of individual utilities. This is equivalent to maximizing the utility of one person whose utility function is like Equation 2 and whose sense of belonging σ is set to its maximum value of 1, meaning that the individual cares as much for others as they care for themselves, the Golden Rule of morality.

Eswaran shows that the efficient choice of food production made by a social planner maximizing egalitarian social welfare would be less than the food production generated by the private property situation. Food is overproduced when land is privatized. Production and income may be maximized, but utility is not.

This illustrates the notion that Indigenous communities – if not all communities – have holistic preferences that depend on more than the consumption of goods.

Our next chapter will take us to a very different place, to a time with a very different mindset. In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, Europeans were searching the seas for new trade routes and new products to sell. Peoples, cultures, and ecosystems were to become collateral damage in the explorers’ search for wealth and the colonizers’ attempt to control it.

- Presentation to author by David Thunderbird Bear, Moose Cree First Nation, August 2018 ↵

- Balsam (2021) ↵

- Ibid, p. 49 ↵

- See the story told by Nellie Taylor in Ignace and Ignace (2017, p. 209) ↵

- Page 45 of “Home is the Hunter (2008)” by Hans M. Carlson ↵

- Oral tradition of Abel Chapman, Cree, recorded in Beardy and Coutts (2017). ↵

- See for example chapter 8 of Sewépemc People, Land, and Laws (2017) by Marianne and Ronald Ignace ↵

- Ibid (2017) ↵

- Secwépemc People, Land, and Laws (2017), pp. 222-3 ↵

- Among the matrilineal Iroquoian Nations, the male chiefs were chosen by female Clan Mothers ↵

- As relayed by Robert Manuel in Ignace and Ignace (2017), p. 370. ↵

- To read the Great Law, go to http://www.ganienkeh.net/thelaw.html ↵

- Kimmerer(2013), Epilogue.[/footntote] Traditional teachings, expressed in ceremonies like these, maintain a holistic view of life. Wealth among traditional people is measured by having enough to give away. Hoarding the gift, we become constipated with wealth, bloated with possessions, too heavy to join the dance. Sometimes there's someone, maybe even a whole family, who doesn't understand and takes too much. They heap up their acquisitions beside their lawn chairs. Maybe they need it. Maybe not. They don't dance, but sit alone, guarding their stuff. In a culture of gratitude, everyone knows that gifts will follow the circle of reciprocity and flow back to you again. This time you give and next time you receive. Both the honor of giving and the humility of receiving are necessary halves of the equation. The grass in the ring is trodden down in a path from gratitude to reciprocity. We dance in a circle, not a line.[footnote]Ibid. ↵

- Institute for integrative Science and Health (2016) ↵

- Both Mi’kmaw and Kanien’kehá:ka speakers refer to the 7-generations principle. ↵

- Wilson-Raybould (2022) pp. 189-190 ↵

- Bryan Simonee, quoted in Nerberg (2019) ↵

- Lipsey, R. G. and K. Lancaster (1956), “The General Theory of Second Best,” Review of Economic Studies, 24, pp. 11-32. ↵

Traditionally practiced most completely among the First Nations of the Pacific Coast, the potlatch is a community feast where status and privilege are correlated with the value of gifts given. See Chapter 3 for details.

As described in Chapter 2, the CWB is an index number that scores communities on their housing quality, educational achievement, employment, and income.

A utility function computes how much pleasure a person derives from any combination of various goods or activities under consideration.

The public goods problem is one reason that markets don't always work efficiently. Public goods, for example public television broadcasts, are things that anyone can access and enjoy. One more person using a public good doesn't make a difference to the cost of providing the public good. People are unlikely to voluntarily pay what public television is worth to them, as they feel that they are not making any difference and other people probably value public television more. Thus public television cannot be fully funded by donations. Governments and philanthropists have to step up if public television stations are to survive.