The Modern Treaty Era

Thus far in our journey we have not specifically considered the situation of Indigenous people living in the city, though many of the issues we discussed – discrimination, the need for investment, the importance of connectivity –are relevant for city-dwellers.

Thus far in our journey we have not specifically considered the situation of Indigenous people living in the city, though many of the issues we discussed – discrimination, the need for investment, the importance of connectivity –are relevant for city-dwellers.

The 2021 Census reported that about 44% of Indigenous people were living in large urban centers – 40% of First Nations, 55% of Métis, and 15% of Inuit[1]. Among cities, Ottawa-Gatineau had the highest number of Inuit.

In 2016 the city with the most residents identifying as Indigenous was Winnipeg (92,801), followed by Edmonton (76,205), Vancouver (61,460) and Toronto (46,315). While Winnipeg had the most self-identified Métis, over 50,000, most people who identify as Métis lived in Ontario.

The greatest concentration of Indigenous people was found in Thunder Bay, where about 13% of the population was Indigenous, followed by Winnipeg at 12%, and Saskatoon at 11%.

The Diaspora:

As described in Lawrence (2004, ch. 11), urban Indigenous communities are [predominantly] made up of people who have left their home communities, either recently or generations ago. Some chose to move in the spirit of adventure and economic opportunity. Others were pushed to the city by enfranchisement, loss of livelihood, or poverty. Deseronto, Ontario is home to many Kanien’kehá:ka who left the reserve because they could not obtain mortgages.

One challenge for Indigenous people living in the city can be disconnection – disconnection from people who share the same cultural background and same lived experience. This means that emotional support and social networks may be lacking, a lack which is made more problematic by any discrimination or exclusion they may be facing, and any inherited trauma they may be dealing with.

Additionally, Lawrence (2004) believes that the urban lifestyle itself, having a distinct separation between home life and work life (at least prior to the Covid-19 pandemic), encourages individualism and the erosion of traditional Indigenous culture.

On the other hand, urban Indigenous communities can provide safe spaces and cultural renewal for people coming to the city from reserves or rural areas. Cities can offer a broader perspective of what it means to be Indigenous than might exist at some reserves, providing examples of the diversity of beliefs, political orientations, careers, and lifestyles of Indigenous people. Pan-Indigenous social and political alliances can be established in cities. Lawrence (2004; Ch. 12) describes these opportunities, noting that urban environments are the only places where Status and non-Status First Nations can work together in the same organizations.

Young Newcomers to the City:

Many Indigenous youth leave remote areas to attend high school in urban centers. This can open up a new, empowering chapter in their lives. But it also exposes them to stresses and risks. They may be hosted by families or schools which lack appropriate cultural understanding. And even the friendliest and best-equipped hosts may be unable to quench homesickness or prevent youth from going out and engaging in risky behavior in the new, unfamiliar milieu.

Other Indigenous youth come to the city for excitement and freedom. Some are escaping poor living conditions or abuse at home. Home might be a foster home or a group home. These youth are at special risk of coming under the control of pimps.

Human trafficking no doubt accounts for many of the Indigenous girls and women making up the 1,181 recorded by the RCMP as having gone missing or having been murdered between 1980 and 2012.[2] Some of them were hitchhiking to the city. Highway 16 in British Columbia is now called the Highway of Tears because of the many who have disappeared along it.

Push factors creating the supply of trafficked individuals – and also of criminals – include unemployment and poverty, abuse in the home or home community, lack of credit or educational opportunities, ignorance on the part of the new, host community, and indifference on the part of the new, host community.

The major pull factor creating demand for trafficked individuals is the profit which can be earned from forcing people to work unpleasant jobs in gangs, round the clock, at low or no wages. This kind of labour is a feature of many occupations including prostitution, agriculture, construction, sweatshop manufacturing, and live-in caregiving.

Part of the fight against human trafficking is education about the risks, directed at potential victims and potential host communities. We should also invest in safety and support for people coming to cities. One example would be subsidizing bus services between cities and towns. Greyhound Canada cut all but one of its bus routes west of Sudbury, Ontario, in 2018, and in 2021 announced the elimination of all Canadian routes.

It is also important that remote and reserve communities become more attractive places to live.

Indigenous Rights in the City

Recall Tom Courchene’s comment that the federal government has typically believed itself responsible to “Indians on land reserved for Indians” rather than “Indians and land reserved for Indians.” This is true of the voting public as well. Even the Supreme Court of Canada, in rulings such as R. v. Van der Peet (1996) and Delgamuukw v. BC (1997), has codified the sentiment that Indigenous people have rights so long as they are on their pre-contact territories following their pre-contact way of life.

Since Indigenous rights are usually understood as land rights, or rights exercised on reserve, many Canadians assume that Indigenous people who move to the city are giving up their Aboriginal rights and adopting mainstream, western values[3]. Little attention has been paid to what Indigenous rights in the city might look like.

Friendship Centres:

Into this vacuum, Friendship Centres arose in the 1950s. They are still important community hubs today. Many colleges and universities now have similar facilities in place, offering Indigenous students counselling, the perspective of visiting elders, ceremonies, social events, job boards, information about scholarship and employment opportunities, and more.

The contributors to Evelyn Peter’s 2011 study of urban Indigenous policy agree that Friendship Centres have been the principal agents of positive change in urban Indigenous life, and have represented the concerns of urban Indigenous people better than have Indigenous political organizations. Indigenous political organizations, such as the Assembly of First Nations, the Congress of Aboriginal Peoples, the Métis National Council, and their provincial counterparts have at times been less sensitive to urban issues. They have, however, provided a useful emphasis on rights.

The Indian and Métis Friendship Centre in Winnipeg developed the first Indigenous Social Housing program in Canada, Kinew Housing. Kinew Housing (established 1970) is still in operation today.

Indigenous-specific social housing can:

- Bypass racism in the housing market

- Provide space for group activities and decision-making

- Provide access to counselling and services

- Celebrate Indigenous identity through building design and décor

The need for housing assistance is real. Anderson (2019), using data from the 2016 Census for Indigenous people living in cities, concludes that Indigenous people are more likely to be renting rather than owning, and to be living in subsidized housing. Home ownership rates have been increasing since 2006, though, from 40 to 43% for First Nations people, from 45 to 48% for Inuit, and from 57 to 61% for Métis. Indigenous people are still more than twice as likely as non-Indigenous to live in a home requiring major repair, though gains have been made since 2006. On a brighter note, Indigenous urbanites are actually less likely to live in crowded housing than non-Indigenous. The rate of crowding has been falling also.

The geographic distribution of Indigenous people has become less concentrated. Anderson (2019) computes a “dissimilarity score” from 0 (evenly distributed) to 1 (living completely separate) for 49 cities in Canada. Only Toronto (score = 0.36) and Regina (0.31) have scores indicating a moderate degree of geographic dissimilarity. Within neighbourhoods having a concentration of Indigenous households, Indigenous households are more likely to be low income and their homes are more likely to be crowded and in need of major repairs.

Government Funding

Not until 2016, with the Supreme Court’s Daniels v. Canada ruling, did the federal government have to accepts its responsibility towards non-Status First Nations and Métis people. But the government had for some time been considering what self-determination rights non-Status people might have, as per the 1982 Constitution Act.

In 1998 the federal government launched its Urban Aboriginal Strategy (UAS), ostensibly to address the socio-economic gaps between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people in cities. UAS offered federal funding for Indigenous programs in cities having at least 5% Indigenous population. Some of this funding required the respective province and city to contribute as well.

The UAS donated to Friendship Centres, and used Friendship Centres to call for proposals and distribute money to programs. In 2013, the National Association of Friendship Centres reported that it had received $16.1 million of federal money and that it had channeled to other Indigenous programs around $37 million of federal money, $39 million of provincial or territorial money, $4.5 million of municipal money, and $4 million from non-governmental and other Indigenous organizations.[4]

Funding to urban Indigenous people, like funding to reserves, has tended to be project-based. It requires applications and tends to be short-term. This creates burdensome paperwork, an inability to plan long-term, and unnecessary rivalry among Indigenous organizations applying for the funds. In its 2017 review of the Urban Aboriginal Strategy[5], the federal government agreed that the funding needs to be more flexible, predictable, and timely.

Like Wolf Collar’s recommendation that Band Councils focus on strategy, not service delivery, Hanselmann (2002) has recommended Indigenous political organizations be consulted by the federal and provincial governments on issues and policy, and that Indigenous community service providers such as Friendship Centres be consulted about service delivery.

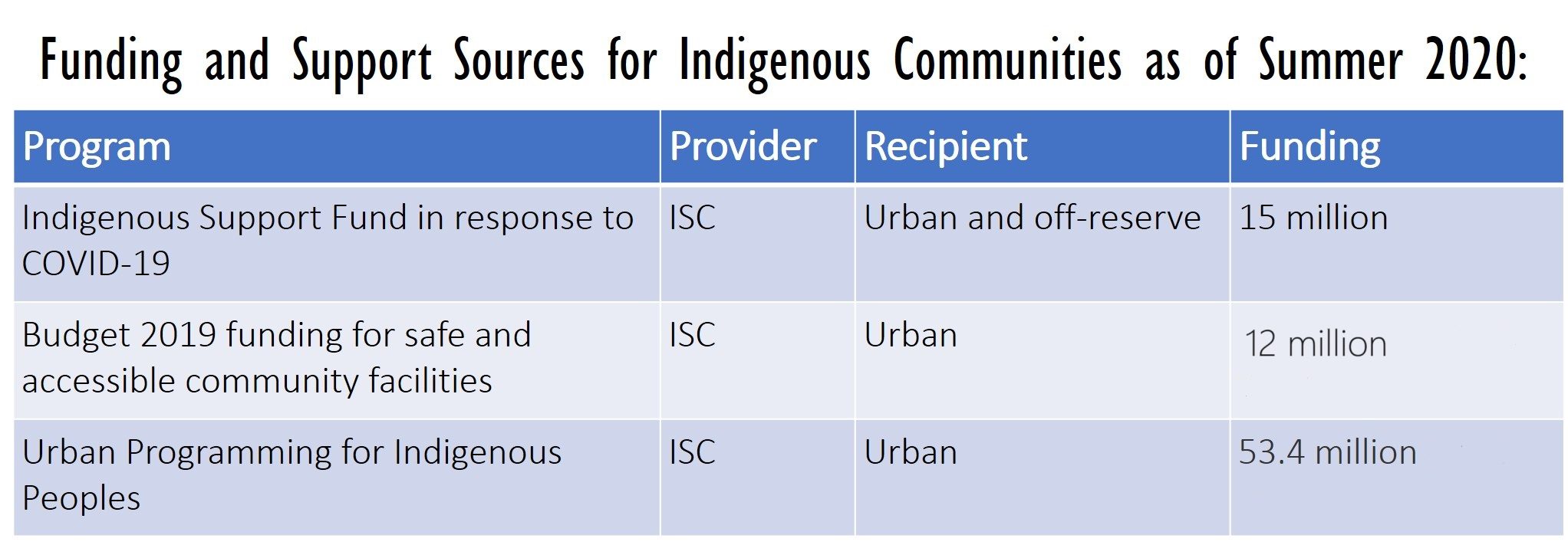

The Urban Aboriginal Strategy was revamped in 2017 and renamed UPIP, Urban Programming for Indigenous Peoples. It was set to distribute about $53 million dollars per year. While much of this money would eventually be matched by provinces, territories, and cities, I think we can agree that this is not a lot of money to be spread among all the cities in Canada having at least a 5% Indigenous population. As the pie chart on the next page shows, federal government spending on off-reserve Indigenous programming was less than 1% of the total amount spent on Indigenous services in 2018-9.

![Spending on Urban and Off-Reserve Indigenous Communities in Comparison to Total Government Expenditures (By GC InfoBase Expenditures in 2018-2019). Graph consolidated by: Pauline Galoustian, 2020. [181]](https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/sites/1088/2021/04/adfghjk-scaled.jpg)

Some 2020 numbers are shown below.

Community Services:

Here are some examples of services available to Indigenous people in the Toronto area.

Council Fire Native Cultural Centre began in 1976 as a small group, gathering for a weekly potluck dinner. It is now a large community center serving over 200 people daily. The Centre has an open “Gathering Place” for people to drop in and receive assistance of any kind – food, housing assistance, friendly companionship etc. A big part of the vision and mission of the Cultural Center is reconnecting Indigenous people with each other and their shared culture.

Anishnawbe Health Toronto, incorporated in 1984, is funded by Ontario’s Ministry of Health and supported by the Anishnawbe Health foundation. It offers more than 60 programs and services including access to elders and traditional healers, training in traditional healing, sweat lodges and other ceremonies, dental care, diabetes prevention, counselling, and mental health care, all according to Anishinaabe vision and principles.[6]

According to its website, Anishnawbe Health Toronto serves over 27,000 clients each year, with nearly 20% of clients being under 21 years of age.

Native Child and Family Services. Serving children and families since 1986, NCFS began taking responsibility for child welfare in 2002. It became an official “Children’s Aid Society” in 2004 after a court battle. NCFS emphasizes holistic preventative care based on best practice, Indigenous values, the right to self-determination, and the importance of extended family and community.

Aboriginal Legal Services was established in 1990 in order to provide culturally appropriate legal alternatives. Among other things, ALS staff prepare Gladue Forms and reports for 22 different Gladue courts (as referenced in Chapter 28), host talking circles for families in crisis, and advocate for changes to Canadian law. They also hire Indigenous legal workers to make clients aware of their rights and help them to find legal counsel.

Bear Clan Patrol Inc. Community Initiative:

The Bear Clan Patrol Inc. is an Indigenous volunteer organization with chapters in 13 cities and more than a dozen other communities across Canada. Inspired by the traditional role of the Bear Clan in Anishinaabe society, a role which includes protecting the community, Bear Clan patrollers walk the streets at night. Their motto is “Community People Working with the Community to Provide Personal Security”. By being physically present in the neighborhood, Bear Clan patrollers are able to provide safe escort for people who need to be outdoors at night. Their presence deters crime, and helps resolve conflicts. They can also refer people on the street to social programs. Bear Clan Patrol offers “Youth Mock Patrol” on select days, which allows the youth in the community to get involved and learn to keep the streets safe.[7]

Founded in Winnipeg in 1992, the Bear Clan Patrol eventually went through a hiatus, but resumed in full force after the 2014 murder of Tina Fontaine, an Ojibwe-Saulteaux teen, in Winnipeg. The murder of this young woman also catalyzed the establishment of Canada’s National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls beginning in 2016.

Leadership:

Indigenous people in the city have no specifically Indigenous political representation. Those leaders who arise to speak for Indigenous people in the city are not elected, and may be self-appointed individuals with their own agendas. However, great good has been done by many selfless urban leaders. One such leader was Vern Harper (b. 1936), Toronto’s “Urban Elder”.[8]

Elder Harper, whose Cree name was Asin, was politically active, organizing a cross-Canada trek to highlight broken treaty promises, and taking on the role of Vice President of the Ontario Métis and Non-Status Indian Association. He also served the Toronto Indigenous community in many concrete ways: co-founding the First Nations School of Toronto, working as youth court worker with Aboriginal Legal Services, and becoming Resident Elder at Toronto’s Centre for Addiction and Mental Health.

As we reflect on a leader like Elder Harper, we are in a good frame of mind to wrap up what we have learned in this course. Concluding thoughts are in the next and final chapter.