Economies prior to the late 20th Century

Before encounters with Europeans became frequent and lasting, the Indigenous people of Turtle Island sustained themselves through what Europeans would understand as hunting, gathering, production, innovation, and trade. Indigenous peoples themselves understood their way of life holistically; economic activity was not something done for its own sake. Economic activity was part of living in relationship with human and non-human entities past and present. The Land and its inhabitants furnished human beings with what human beings needed, and human beings in turn respected and cared for the Land.

In this chapter we focus on the material lifestyles of six broadly-defined cultural groups: Pacific First Nations, Plateau Peoples, Bison-Hunting Peoples, Woodland Hunting Peoples, Arctic Peoples, and the Iroquois. Each cultural group developed production methods and economic norms in harmony with the Land to which they were related.

The map below gives an approximate indication of the traditional territories of these cultural groups. One thing all these groups had in common is that their technologies were simple. Using those simple technologies they survived and often thrived across a wide variety of landscapes and climate zones.

Indigenous Technologies

Everywhere in present-day Canada, First Nations and Inuit relied heavily on stone and bone tools. Copper, however, was collected from various sites, heated, and worked into items such as ornaments and the arrow tips shown in the photo below.

There were iron tools among the Inuit at least since the thirteenth century, having been cold-forged from a meteoritic deposit in Greenland (Culligan, 2016) or being the result of trade between Inuit and others in the Far North, for example Norse colonists in Greenland. Yet rock, bone, and wood were the most important materials for making tools. Rock was used for knives, arrowheads, spear tips, even bowls and containers in the Arctic. Bone was used for knives, scrapers, fish hooks, and sewing needles.

The tools which are still with us today are respected as ancestors according to some Indigenous traditions, since they are made of natural materials.

![This arrow made of antler and tipped with 99.9% pure copper, is estimated to have been manufactured around 1080 AD. It was found in melting ice in 2016 on the traditional territory of the Carcross/Tagish First Nation south of Whitehorse, Yukon. Photo Credits: Government of Yukon [20]](https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/sites/1088/2021/02/5.jpg)

Before European contact, there were no cart wheels, pottery wheels, or modern horses. The most important non-solar energy sources were fire, manpower, and dog power. In hunting, the prey animal’s own energy could be used, as when bison were frightened into stampeding over a cliff.

The only fabric was found on the West Coast, woven from dog wool or cedar bark and other plant fibers. Clothing was usually made of leather and fur. Beads were made of shell. Porcupine quills as well as shell beads were used to decorate clothing.

![This wampum belt, known as the Hiawatha belt, represents the coming together of the Seneca, Cayuga, Onondaga, Oneida and Kanien’kehá:ka (Mohawk) to form the Haudenosaunee. The first example, no longer surviving, would have been made at the time of this treaty, perhaps 1450 AD. Photo credit: CUPE Ontario [21]](https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/sites/1088/2021/02/hiawatha_belt_purple.jpg)

Beads were important. In the west, dentalium shells were used as money. In the east, whelk and clam beads were woven into purple and white wampum belts which served either as precious gifts or records of treaties. Across the continent, most trades did not involve the exchange of money, but were bartered.

The cultures of Indigenous Canada were oral cultures, relying not on writing but on storytelling to pass on knowledge and values. Words spoken in treaty-making processes were taken as seriously as a written contract would be today.

Numeracy and math were not advanced. However, Indigenous people were able to keep track of trade deals and borrowing obligations. The ceremonies which accompanied trading helped cement transactions in the participants’ memories.

Trade between First Nations was extensive. Without that trade, survival might not even have been possible for many groups.

Trade

- Gives a community access to goods not available locally

- Gives a community a source of goods in bad years (drought, bad hunting outcomes, disease)

- Gives all participating communities some of the extra that can be produced when communities specialize

From early on, corn and fishing nets were exchanged for fur and fish around the St. Lawrence and Great Lakes. Soft pipestone from Minnesota was used throughout present-day Canada. Flint from northern Labrador and copper from Lake Superior were brought to the St. Lawrence River valley. Fish oil was traded up and down the west coast and into Alberta and Montana. And eventually, horses from the Spanish in Central America found their way to the Prairies through the Indigenous trading network.

An axe traded by American explorers Lewis and Clark made it to the west coast before they did (1806). In fact, it appears that goods were traded from northern Asia across the Bering Strait as recently as 1440-1480 CE. In 2021, American archeologists announced finding glass beads from Venice in three Alaskan sites dating to that period.

On Specialization:

Note that, of the 26 entries in the previous table, most are Pacific Coast societies. Trade and specialization flourished along the resource-rich Coast, fueled by prosperity and fueling prosperity. In less prosperous, more isolated areas, trade was less of an engine for growth. Is that true today also? Why?

While economists usually assume that specialization is efficient, yielding more output to be divided between participants, diversification can be the more efficient choice when production is precarious and outcomes are uncertain. For example, when the environment provides only scanty biomass, and hunting and gathering is often unsuccessful, everyone needs to be on the lookout for edibles. No member of the tribe can be spared from this basic task.

Resource-poor areas had a triple disadvantage economically. First, they had fewer resources with which to work. That likely included a smaller “labor force” as well. Second, they could not risk specialization, so their trading opportunities were limited. Finally, lack of trade would negatively impact their ability to discover new ways of doing things.

Let’s now focus, one by one, on specific cultural groups and their material economies prior to European contact. We begin with the Peoples of the West Coast.

Let’s now focus, one by one, on specific cultural groups and their material economies prior to European contact. We begin with the Peoples of the West Coast.

People of the Pacific Coast

Half of Canada’s Indigenous language families are found on the Pacific Coast, suggesting that the Pacific Northwest has been inhabited for a longer time than anywhere else in Canada, and that this area could have been the cradle of nations that eventually migrated east and south. The first people on Turtle Island are thought to have come from Siberia over a land bridge exposed during the last great ice age. Another possibility is that Polynesians came to the Pacific Coast on boats carried by ocean currents and trade winds.

The recent discovery of a stone fishing weir, about 14,000 years old, under the waters around Haida Gwaii (Queen Charlotte Islands, BC), attests to millennia of human habitation on the Pacific Coast.

Although the First Nations along the coast of present-day British Columbia differ in significant ways, they all share a connection to the ocean or ocean-feeding rivers. Their lifestyles were similar and their economies were integrated. In what follows we will consider them a single cultural group.

Pacific Coast societies were blessed with a gentle climate and with rapidly renewing resources such as lumber, sea mammals, fish, and shellfish. Cedar and salmon were the two most important resources. Red cedar (thuja plicata) is lightweight, strong, rot-resistant, and easy to split into planks, or carve. No sawing was necessary. Its trunks were used for dugout canoes, its bark and roots for baskets and clothing, and its branches for rope.

Salmon, a large, nutritious fish which breeds in rivers, swims out to sea, and returns to rivers to spawn, was the other great boon. As McMillan and Yellowhorn (2004) explain, salmon arrived at predictable times and locations, and was abundant, easy to catch, and easy to preserve. Surplus salmon was dried for year-round use. The ocean and rivers provided a variety of other fish, sea mammals, and shellfish. Of special note is the eulachon, a fish that was fermented, then cooked to release a valuable oil used for food, medicine, lubrication, and fuel. Eulachon oil was traded extensively along the coast and into the interior of the continent. The language of commerce was based on Chinook, the language of a people living in present-day Oregon and Washington State.

The Prosperity of Pacific Culture:

The prosperity of Pacific Coast Nations prior to European contact is evidenced by extensive arts and crafts, including highly ornamented everyday objects, many of which have survived. These imply leisure time, tools, and the uninterrupted intergenerational transmission of specialized skills.

Another indication of prosperity is the survival of villages at particular sites for hundreds of years. Communities tended to split up during the warmer months to visit prime fishing and sea mammal hunting places, returning in winter to their communal houses. Summer camps and winter houses persisted in the same locations.

Other signs of prosperity are the production of luxury goods and their distribution during feasts, extensive travel for social and diplomatic purposes, the production of goods for export, and innovations in production and finance.

Technical innovations include the intentional placement of fertilized salmon eggs in selected rivers and streams; extraction of fish oil; farming clams, crabs, urchins, kelp and fish by building rock walls near the low tide line; and not fishing for salmon until two weeks after the first salmon arrived at freshwater streams from the ocean. This last custom would select for early-arriving salmon. (Anderson, 2016).

The poverty trap is the condition where a society is too poor to save. This was not operational here. Houses, boats, and even slaves were accumulated. After contact with the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC), homes across the region featured chests for storing HBC blankets. The blanket became the standard unit of money. Five-blanket cedar chests were used to store this currency.

Recall that economic growth requires inputs, efficiency, and trade. In terms of increasing inputs, these societies invested in the production of tools such as canoes, hooks, and fishing traps. We call such things capital because they provide services time and again. Tools, equipment, houses and boats are physical capital. There are also other kinds of capital such as human capital (knowledge, skills, experience) and natural capital (stocks of salmon and cedar).

West Coast Peoples took steps to selectively improve the salmon stock as explained earlier. There is no evidence that they overfished or overhunted marine stocks. Thus, their natural and physical capital stocks improved, providing a larger annual flow of inputs than before.

Fractured Land Hypothesis:

Efficiency in production was likely fueled by competition – both economic and military – along the Coast. According to the Fractured Land Hypothesis, described by Jared Diamond in his book Guns, Germs, and Steel (1999), a jagged coastline fosters economic growth. Diamond contrasts the relatively smooth coast of China with the irregular coasts of Europe, arguing that the nooks and crannies in the European coastline made possible the proliferation of many competing city-states.

With many coastal fjords, bays, and islands offering safe havens and protected access to streams and rivers, the Pacific coast offered plenty of nooks in which a diversity of communities and an extensive network of trade could develop.

Production, specialization, and trade were promoted by the celebration of potlatch. This traditional feast served many functions, from peacemaking to money creation.

The Potlatch – A many-splendored thing:

The potlatch is a multi-day feast hosted by one community for its own members or for a visiting group. The potlatch may mark an important milestone such as a marriage, inheritance of a leadership position, or erection of a totem pole. All members of the community are invited, and all who attend bring items to give away. Traditionally, the host community’s Chief would attempt to outdo himself and previous hosts by giving away more than was previously given and more than anyone else in attendance. Prestige was and is correlated with the amount given away. There is an expectation, however, that the recipient community will in future hold a potlatch of its own, where they will attempt to return and outdo the generosity they have just experienced. And recipients within a community will in future give back at least as much as what they have received.

![Modern Potlatch - Chief Alan Hunt’s Potlatch Ceremony (people surrounding a fire and food), Kwakwaka’wakw First Nation. Photographer: Gregoire Dupond/BC TimeSlip, With permission from: Alan Hunt [29]](https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/sites/1088/2021/02/DSC1113-copy-1200x801-1.jpg)

Let’s pause for a moment and imagine Canada or the international community following this principle – prestige from giving away. It is breathtaking.

Meanwhile, this principle might have led to some confusion at the point of European contact. A gift given by a Haida chief to a British official, for example, might have been interpreted by the British official as tribute, as the chief acknowledging the official’s power. But the gift might have been intended by the chief to awe the official, by demonstrating the chief’s wealth and power. The chief might interpret the official’s acceptance of the gift as the official acknowledging the chief’s dominance.

Economics of the Potlatch:

Carlos and Lewis (2016), and Johnsen (2016), explain that the potlatch was not only an expression of the community’s deepest values but also a vehicle for several economic and financial outcomes.

- Redistribution. Kwakwaka’wakw leader Jody Wilson-Raybould writes that the accumulation of wealth by individuals was considered morally wrong in her own and other Indigenous societies. The potlatch served to redistribute wealth.[1]. Since no one was forced to return or pay for what they received, those who truly needed the gifts could hang on to them. The only cost was to your reputation, which served as your credit score.

- Allocation. There is evidence that potlatches reinforced property rights to salmon streams and compensated those without ownership. During potlatches among the Southern Kwakiutl of BC, a chief asserted various privileges, and acceptance of his gifts implied that recipients had no objections to his claims.

- Resolution of conflicts. As above, the potlatch provided an opportunity to compensate less privileged people or bands who might otherwise be upset by unequal distribution of assets and privileges.

- Conservation. By confirming the right of certain individuals or families to particular streams, the potlatch helped prevent those streams from being over-exploited.

Another way the potlatch promoted conservation was that the prospect of attending another community’s potlatch, or the ability to delay hosting a potlatch, could allow a community to refrain from overharvesting the few salmon that had arrived during a bad year.

- Borrowing. If one person receives something from another, with the expectation that they will give back something at least as valuable in the future, we have a system of borrowing at a rate of interest. Large loans were made at potlatches using meter-high copper plates engraved with the family crest of the first person to sell the copper plate.

![Haida Nation copper plate. Credits to: Canadian Museum of History Archives (CC BY-NC 2.0) [28]](https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/sites/1088/2021/02/haacp14b.jpg)

Each “copper” represented more money than what the copper itself was worth. The copper was like a bond, a statement of accounts receivable. The holders of these copper plates could ask for the money back at any time. More money, specifically HBC blankets, would have to be returned than what was last “paid” for the copper.

- Implicit Money Creation. Not only were copper plates created to represent more blankets than the copper content was worth, but also, as the same blankets were borrowed and leant out again after the borrower used them to buy something, and as the copper plates themselves might be sold or loaned, the total amount of debt in existence would exceed the physical number of blankets.

- Saving. The one who lends to the borrower is the saver. I give now, perhaps only for the assurance that I will receive, with interest, in the future.

- Accounting. The public witnessing of transactions eliminates the need for written contracts in a pre-literate society. The more elaborate the ceremony, the more likely it is to be remembered.

- Insurance. The growing stock of items which are created but never actually used serves as insurance for times when those items might actually be needed.

Leading anthropologist Franz Boas wrote about the Kwaikutl potlatch in 1897:

Leading anthropologist Franz Boas wrote about the Kwaikutl potlatch in 1897:

“The contracting of debts…and the paying of debts…is the potlatch….This economic system has developed to such an extent that the capital possessed by all the individuals of the tribe combined exceeds many times the actual amount of cash that exists….The sudden abolition of this system…destroys therefore all the accumulated capital of the Indians….”[2]

Boas also noted that blankets were lent out at high rates of interest among the Kwakiutl people, suggesting a shortage of credit. The rate of interest was around 25 blankets per year for every 100 borrowed. A person with a poor credit history could pawn his or her name and associated rights for one year in order to borrow a substantial number of blankets.

Credit scarcity has been associated with slavery by Fenske (2009), and there was indeed slavery among West Coast peoples. Pawning yourself or your children is a way to raise money. And enslavement is a way to resolve bankruptcy.

Slavery is also associated with places where there is little in the way of investment opportunities. The West Coast people seemed to have plenty of investment opportunities: they could build canoes and tools, fishing equipment and weirs, and they could manage rivers and streams.

But perhaps the investment opportunities were limited by the ability of the financial system to keep track of them and the limited amount of money to transact them. Potlatches may have been too infrequent to facilitate all the lending that was needed. Perhaps too many people were excluded from the investment opportunities associated with fishery management. Perhaps access to fishing grounds, sea mammal hunting grounds, canoes, equipment, and tools was very unequal.

Then common folk, as opposed to privileged members of society, would have few ways to acquire wealth other than to pawn themselves or their dependents for access to those capital goods. They might easily become slaves if they became unable to pay their debts.

The potlatch was practiced unchallenged for a long time after Europeans first penetrated the East Coast. For reasons which are unclear, an 1884 an amendment to the Indian Act outlawed the potlatch. Any person participating in, encouraging, or organizing a potlatch would be “guilty of a misdemeanor and shall be liable to imprisonment”. Not until 1951 could potlatches again be celebrated openly. [3] We see that West Coast society was complex and furnished a healthy standard of living, though not all members of society shared equally in its prosperity.

We see that West Coast society was complex and furnished a healthy standard of living, though not all members of society shared equally in its prosperity.

On the Great Plains, societies were less complex and less prosperous, but fairly nutritionally secure, thanks to vast herds of bison.

Before we move on to consider the Great Plains, we should note some unique features of a cultural group living between the Great Plains and the Pacific Coast, on the Interior Plateau of present-day British Columbia.

Peoples of the Plateau

Until 200 years ago, Plateau First Nations lived in villages of underground pithouses during the winter. While they hunted and fished, the most important components of their diet were salmon and starchy root vegetables such as balsam root, nodding onion, riceroot, biscuitroot, and glacier lily.

These tubers, rhizomes and bulbs of these plants were harvested, then intentionally exposed to sunshine to convert some of the starch to sugar. When fully ripened, these products were cooked between hot rocks and burning foliage in pits. This further converted their starches to digestible carbohydrates.[4]

The Plateau peoples tended and improved berry patches and the places where they collected the starchy roots. For details of these quasi-agricultural activities, see Ignace and Ignace (2017, pp. 190-1). As did First Nations elsewhere in Canada, the Plateau peoples used controlled burning to repel insects and weeds, and to create grasslands for deer and elk.

Bison Hunting Peoples

The Great Plains is a grassland two thousand kilometers across, from Alberta to Manitoba. This Prairie ecosystem continues into the United States all the way to Texas. Plains Nations who lived in present-day Canada at the time of European contact include the Assiniboine; Sioux Nations such as Blackfoot, Nakota and Lakota; Grosventre; Nêhiyawak; Plains Ojibwe; and Sarcee.

On the Great Plains roamed bison, as many as 30 million of them. For thousands of years the bison provided First Nations with meat, sinew, fat, hide, bone, horn, hair and dung. Even the hooves were used – boiled down to make glue.

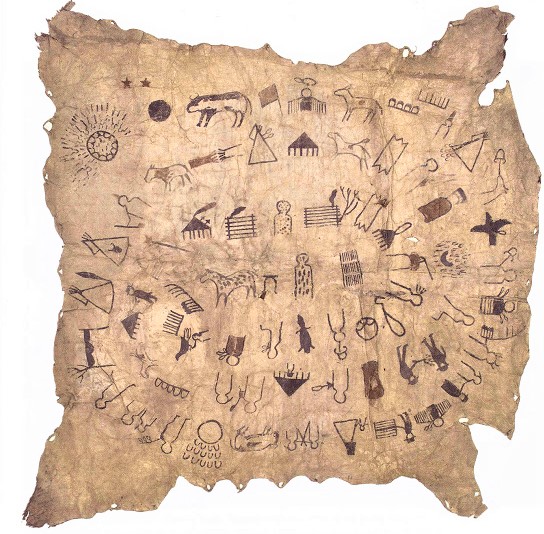

The dried meat of the bison was pounded, then mixed with dried berries and bison fat. The resultant “trail mix” called pemmican could remain edible for three years. Pemmican was widely traded. The hide of the bison provided warm blankets, clothing, footwear, tent materials, and snares. It was also used as parchment to make pictographic records of natural events, weather, and food supply known as “Winter Counts”.

Bison were stalked and assailed with arrows or spears, herded into corrals known as “pounds”, or chased off cliffs. The arrival of the horse, which was established on the Plains by 1780, made bison hunting more efficient, selective and safe. But guns were not preferred by First Nations in bison hunting because of their noise and their tendency to stampede the herds.

Carter (1990) describes the annual calendar of the Nêhiyawak (Plains Cree). They would gather in prime bison grazing areas, on the southern grasslands, in the early summer. While they decided on their hunting strategy, members of the Cree Warrior Society would police the camp and make sure no hunter or mischief-maker scared away the nearby herds. When the timing was right, the hunters would surround a herd and drive it into a pound for slaughter. After a few weeks of hunting and processing the meat, the community, like the bison herd, dissolved into smaller groups which gradually moved toward winter territories in river valleys and wooded hills where the snow would remain soft enough for bison to dig. As the Nêhiyawak migrated, plants were gathered, especially the prairie turnip, which was dried and pounded into a vitamin C-rich flour. In the autumn and winter the Nêhiyawak continued to hunt bison in small groups, again by driving them into a pound, sometimes by using smoke or imitating the cry of a frightened bison calf.

Note that bison were hunted collectively. One reason had to be that hunting these massive herding animals would be difficult without help. Also, hunters coming at the herd from uncoordinated directions would scatter the herd, making bison more difficult to find and causing the bison more distress. Another reason, posited by Carlos and Lewis (2010), is that collective ownership with central decision-making minimizes overhunting.

![Plains Bison. Photo by: Daoud Alahmad (Public Domain) [31]](https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/sites/1088/2021/02/28960251194_1693235572_k.jpg)

In addition to bison, winter hunting bagged moose, elk, deer, and smaller animals. In the spring, fish were trapped in weirs, geese and ducks were hunted, and maple syrup was processed into sugar. The Plains peoples were among the tallest in the world (Feir, Geillizeau and Jones, 2017). This attests to the nutritious and plentiful bison meat available. The selective effect of war, hardships, and infanticide could also be part of the explanation.

There is evidence that intertribal conflict was frequent among the Nations of the Plains, even before contact. Treuer (2014) writes, “The Lakota and Nêhiyawak (Plains Cree) assumed powerful military positions. But it came with a price. The Plains offered very little geographical separation between tribal areas and very little natural protection for tribal populations. Everyone was vulnerable in times of war.”

Plains people were not able to live in permanent settlements, nor to devote as much time to artistry, nor to leave behind as many lasting artefacts as were Pacific Coast Peoples. We can conclude that their material standard of living was not as high. The same can be said of pre-contact Woodland Hunting Peoples. Some in the more southerly, biodiverse forests would have had standards of living similar to or better than the Bison Hunting Peoples, while others in more northerly forests would not.

Woodland Hunting Peoples

Like the Great Plains, the forests of Canada are more contiguous and open than Pacific Coast habitats, more exposed to rivals and less conducive to independent political and economic development. Resources are less abundant. While hunting, fishing, and gathering conditions are better in more southerly areas, such as the Maritimes, the St. Lawrence River Valley, and the vicinity of the Great Lakes, most of Canada’s woodlands lie above the 49th parallel and present considerable survival challenges.

According to Professor Kenneth Hare, “In the north, there is only a very limited number of species… and most of them are highly specific. They have exact requirements and they are adapted to a specific environment.”[5]

Not only is there a limited number of species, but animal and plant growth is limited by the cold climate and short growing season. Thus the density of game animals is low. It has been estimated by Carlos and Lewis (2012) that a population of 1000 moose is needed to provide enough meat to feed 83 human beings during the coldest six months of every year on an ongoing basis. 1000 moose in the Hudson Bay lowlands require two thousand square kilometers of habitat. Hence two thousand square kilometers for 83 people to live sustainably – one person per 24 kilometers squared. In the 1850s, an area of hundreds of thousands of square kilometers in present-day northern Quebec was estimated to be home to 135 hunters and their extended families.[6]

Many of the game animals, such as moose and deer, travel alone, so that a hunter cannot take more than one at a time. The long distances traveled, and the great exertion required for hunting, made hunting more dangerous, especially when hunters had to travel over ice. The Cree living in the hinterlands of Hudson Bay and James Bay were one of the peoples mastering this lifestyle. Within their tribes, each family or group of families had territories they considered their own, to which they returned seasonally.

The Cree living in the hinterlands of Hudson Bay and James Bay were one of the peoples mastering this lifestyle. Within their tribes, each family or group of families had territories they considered their own, to which they returned seasonally.

In addition to hunting, trapping and gathering, they shaped their environment by selectively burning forests to create grazing land for deer, caribou, and other ruminants. As in other regions of Canada, woods were managed with fire to create a mix of old and young forest, woodlands and meadow (Regan (2022)).

Carlson (2008) describes how Cree bands came together in the summer for fishing and socializing at particular locations, but in the autumn, they broke into groups of 2 or 3 families. After hunting geese along the shore of Hudson Bay or James Bay, these small hunting parties would travel to winter campsites while collecting fish and meat to dry for winter.

After a month at the first hunting site, the group would take advantage of waterways not yet frozen to travel to a new site, close to fur-animal hunting areas. Here they would build a communal lodge instead of tents or migwams. Late fall is the best time to hunt for fur, before animals’ fur becomes thinner and looser towards the end of winter.

In the middle of winter, the group would move again to a new site best for hunting large animals for meat. Deep snow makes game animals easier to track and chase. Snowshoes were developed for this purpose. Once spring arrived, it was important to get back to the canoes before the ice melted; otherwise walking would be muddy and slow. Once at their canoes, the group had to wait until the rivers were safe to travel back to their summer campsites. All in all, the distance traveled from winter camp back to summer camp could be more than 50 km. Indeed, much further distances were sometimes traveled for various reasons including finding husbands for daughters, trading, or giving one’s hunting territory a rest.

Like the Cree, other woodland hunting peoples also alternated between intervals of “compact time”, when bands or tribes came together at traditional locations to harvest seasonally abundant fish, geese, or caribou, and “diffuse time”, when families struck out on their own.[7]

In the Arctic

In the Arctic, the hunting of sea and land mammals was the basis of the economy. At peak harvesting times, Inuit people, and the Thule people who preceded them, came together to hunt caribou, seals, geese, whales, and fish. At other times, groups split up, with several families of related men remaining together. To cope with the challenging climate and terrain they developed the winter igloo, the kayak, the dogsled, warm and waterproof parkas, sun goggles, and other inventions.

In general, populations were small and the quest for food imperative, offering little scope for specialization. The distance between communities limited trade. Oral and written histories of imperilment on the breaking ice and of starvation abound, attesting to a precarious existence, at least after the climate began to cool in 1200 CE. McMillan and Yellowhorn (2004) explain that this “Little Ice Age”, which lasted until 1850, caused sea ice to build up to such an extent that whale migration along the north coast was inhibited. There is evidence that Inuit communities became more isolated during the Little Ice Age.

Farming and the Iroquois

In southern Canada, Iroquoian peoples enhanced their food security by growing crops. These peoples included Petun, Neutral, and Wendat (formerly called “Huron”) living along the North Shore of Lake Ontario and between the Great Lakes, and other groups such as the Stadacona living along the shore of the St. Lawrence River. Before European contact, the Haudenosaunee, also farmers, were all living in present-day New York State.

The Iroquois were the only Indigenous people in pre-contact Canada to make farmed goods the mainstay of their diet: corn, beans and squash accounted for about three-quarters of the calories they consumed (Tremblay, 2006). They also grew other plants including sunflowers and tobacco. After the land was cleared by girdling trees and burning the undergrowth, women managed the planting and did most of the farm work.

The Iroquois used the Three Sisters planting technology in which corn, beans, and squash are planted together: the corn acting as a support for the beans, the beans adding nitrogen to the soil, and the squash shading the ground, conserving moisture and retarding weed growth. The corn kernels were pre-soaked in an herbal mixture to make them sprout more quickly; then they were planted in mounds among burnt trees and stumps. These mounds improved drainage and provided a greater surface area, as well as higher elevation, for capturing the sun’s rays. Using the same mounds every year reduced soil erosion.

The Iroquois traded their crops for meat, furs, shells, flint and other goods. They also hunted and fished.

Communities were semi-permanent; summer villages persisted until the cultivated land became depleted of nutrients. In winter, hunters and those family members able to travel would leave the village to hunt for meat and fur.

Oral history and post-contact written records attest to violent raiding among Iroquoian tribes and with other cultural groups; however, the Iroquois also signed treaties and left the legacy of the “Great Law of Peace”, the organizing principles of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy.

We have now familiarized ourselves with the basic features of the economies of West Coast Peoples, Bison Hunting Peoples, Woodland Hunting Peoples, Inuit, and Iroquois. We observe some similarities among them – simple technologies, reliance on natural resources, seasonality of activity and residence, and adaptation to the environment at hand. In our next Chapter we will look at how fertility, mortality and population growth might have been affected by this way of living, and how fertility, mortality and population growth might have affected the standard of living.

- Wilson-Raybould (2022) p. 218 ↵

- Franz Boas, "The Social Organization and Secret Societies of the Kwakiutl Indians. Washington, D.C: Government Printing Office, 1897. ↵

- ICT (2012) ↵

- For details, see chapters 3 and 5 of Secwépemc People, Land, and Laws (2017) ↵

- Library & Archives Canada, Kanatewat, Hare, AA-20, vol. 10, 42, 55. ↵

- Ibid, p. 112 ↵

- 19 Bock, Philip K., “Social Time and Institutional Conflict”, in H.F. McGee (1983) p. 153. ↵

Traditionally practiced most completely among the First Nations of the Pacific Coast, the potlatch is a community feast where status and privilege are correlated with the value of gifts given. See Chapter 3 for details.