The Modern Treaty Era

In our previous chapter, we learned how Indigenous businesses and communities can access money. But money isn’t everything that business needs or that economic development requires. Flanagan and Johnson (2015) found that Community Well-Being Index scores were correlated with a community’s Own Source Revenue, but not with a community’s per capita financial assets. Money needs to be put to work.

Think of money and other assets like wood, and business like flame. But flames need oxygen as well as wood. The oxygen is a supportive, business-friendly environment based on good governance. This is essential to business and economic development.

Aspects of a supportive business environment

A business-friendly environment has reliable leadership, complete legal frameworks, quality infrastructure, and prudent taxation. Says the Tulo Institute:

“…possessing access to resources or having a good location is important, but it is not enough to create economic growth. Both Russia and Peru are well endowed with natural resources; indeed, Russia is also well-endowed with technology and human resources. However, neither country provides a high standard of living because they have been unable to offer the supportive public sector input that is also required. By contrast, countries such as Singapore and Japan have achieved very high standards of living with relatively poor natural resources…The barrier to prosperity on First Nation and tribal lands is an inability to provide sufficient certainty to investors. [First Nations and Tribes] must use the powers available to them now to lower the transaction costs of investment.”[1]

This quotation is from Building a Competitive First Nation Investment Climate, the free online textbook of the Tulo Institute[2]. Many of its lessons are reproduced in this chapter.

The Tulo text tells us that in one 1999 comparison, it cost developers an average of 11 months to get the necessary approvals for projects in Calgary/Vancouver/Kamloops versus 48 months on Siksika/Squamish/Tk’emlups reserves. The financial costs differed by approximately the same proportion.[3]

The Table below shows many of the transaction costs and uncertainties that investors face when considering a First Nation site for their business or project.

![Development Stages and Transactions Costs, Tulo (2014) Chapter 2. [171]](https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/sites/1088/2021/04/nnytbrvecwx-1-scaled.jpg)

How can these uncertainties be resolved, and transaction costs be minimized? Communities must provide quality infrastructure, reliable leadership, reasonable taxation, and a complete legal framework. In a word, good governance, as discussed in chapter 19, is essential.

Quality Infrastructure:

Investors like good infrastructure – roads, parking, water pressure, internet; and they need good services – mail delivery, waste removal, and policing. All of these things improve productivity, reduce the costs of business and attract customers, suppliers, and business partners. Good infrastructure promotes business and economic growth while, in a positive feedback loop, business can be taxed or charged fees to fund infrastructure.

Prudent Taxation:

Communities are better able to supply good infrastructure when they have tax revenues to spend.

Because of amendments to the Indian Act, First Nations have the right to impose property taxes on residents (1988), charge sales tax (2003), and charge fees for services provided to residents (2005).

Would-be investors need to know what these taxes, or any service charges, will be. Taxes, fees, and licenses should be transparent[4], be applied fairly, be predictable, and be reasonably low.

The First Nations Financial Management Board and the First Nations Tax Commission, instituted by the First Nations Financial Management Act (FNFMA), offer sample financial administration laws and tax laws (property tax, service charges, development cost charges, business activity taxes).

As of December 2017, 113 First Nations had developed property assessment and taxation bylaws bylawsunder the FNFMA, and 154 Nations, about a quarter of all First Nations, were collecting property tax;[5] however, the word on the street is that the tax is usually applied to non-member leaseholders, not band members, due to its inherent unpopularity.

Hillel (2019), in a sample of 38 Albertan reserve communities, found that the presence of a property tax in 16 of the communities in 2006 was correlated with income growth, the probability that the correlation was spurious being 22%. She observed that the communities having a tax tend were either the wealthiest or the poorest. She reckoned that was because the wealthiest could afford it, and the poorest would have fewer people liable to tax and upset about it. Keep in mind, though, that the property tax may in many cases apply only to non-member, non-voting leaseholders.

Reliable Leadership:

Leadership needs to be unified, so as to better make the case for investment to community members, and to better communicate with potential investors. Leadership needs to make decisions in a timely manner. There must be regulations in place to protect investors as administrations come and go. Investors need to be confident that the next local election will not reverse the decisions of the present administration.

Complete Legal Frameworks:

Potential entrepreneurs and investors need to be given all relevant information regarding land use and building codes. How high can an office building be built? What standards must be met for septic tanks? The rules must exist, and community leaders need to have those rules at their fingertips. Entrepreneurs and investors want to know that the arrangements they make with the community are rock solid and legally defensible.

Unfortunately, the legal framework around reserve land is incomplete. When it comes to building regulation, health and safety, drinking water, environmental protection, and resource exploration and development, provinces have detailed laws but First Nations typically have only a limited set of federal laws.[6]

There are reasons for the lack of federal regulation. One is that creating and updating laws is an onerous task requiring expertise not usually found at the federal level because these matters (building standards, health and safety, etc.) are usually regulated at the provincial level. Second, the process would have to involve the reserve community, in recognition of the Aboriginal right to self-determination. The new laws created are not necessarily going to be appropriate for all reserves or acceptable to all reserves.

Meanwhile, the Indian Act already allows First Nations to make local regulations concerning zoning, building construction, water services, and other matters, but many First Nations have not developed these regulations.

There is, then, a need for standardized regulations, or a palette of well thought-out regulations from which First Nations might choose. It will be beneficial for First Nations to harmonize their bylaws with those of neighbouring communities.

Bylaws on Reserve

Former Siksika Head Chief Leroy Paul Wolf Collar believes that lack of community laws (“bylaws”) and lack of resources to enforce existing bylaws is a major impediment to First nations’ self-determination. We draw heavily from a chapter of his 2020 book in what follows.

All reserves are subject to the Criminal Code, a federal code. Provincial laws may also apply, but only where the province has jurisdiction, for example on highways and county roads which pass through reserves. The Band itself is responsible for policing reserve-only roads.

The Band can make its own bylaws concerning hygiene and disease prevention, domestic violence and abuse of any kind. The Indian Act section 81 gives a Band Council this right, so long as its laws do not clash with federal or provincial law. The Band must deal with trespassing, evictions, noise, nuisance, fights, and stray animals. In these cases, the Band may sometimes wish for more provincial police or RCMP (federal police) intervention. But the community may also fear provincial police or RCMP intervention, which, as recently publicized incidents attest, has sometimes been brutal.[7]

Wolf Collar recommends that a Band create bylaws around construction and land use as we previously discussed. He also recommends bylaws to protect historic sites and signage, and to discourage property damage, dumping, and parking dilapidated furniture and vehicles. He makes special mention of animals. Grazing animals are sometimes neglected. Packs of homeless dogs are known to be a problem on a number of reserves.

The Benefits of Bylaws:

The benefits of a complete system of bylaws on reserve would include not only an improved business environment but moreover enhanced safety of elders, spouses, children, and animals; a more peaceful and attractive physical environment; and preservation of historic and culturally significant sites and buildings.

To resolve violations of local bylaws, a traditional court system could be developed, allowing the community to follow Indigenous legal traditions such as restorative justice. Any fines or community service could benefit the local community. The community could also benefit from training and employment in law enforcement.

What needs to happen?

For more than a century, the paternalistic attitude and interference of the federal government discouraged Indigenous communities from believing they could lead, innovate, and determine the laws governing their communities.

Today, Indigenous communities may need legal and financial assistance to draft bylaws.

Once bylaws are in place, they must be enforced. In an interview with Chief Administrative Officer David Soulière in Tyendinaga in March 2019, he said that his number one wish for the Mohawks of the Bay of Quinte was the ability to enforce existing bylaws[8].

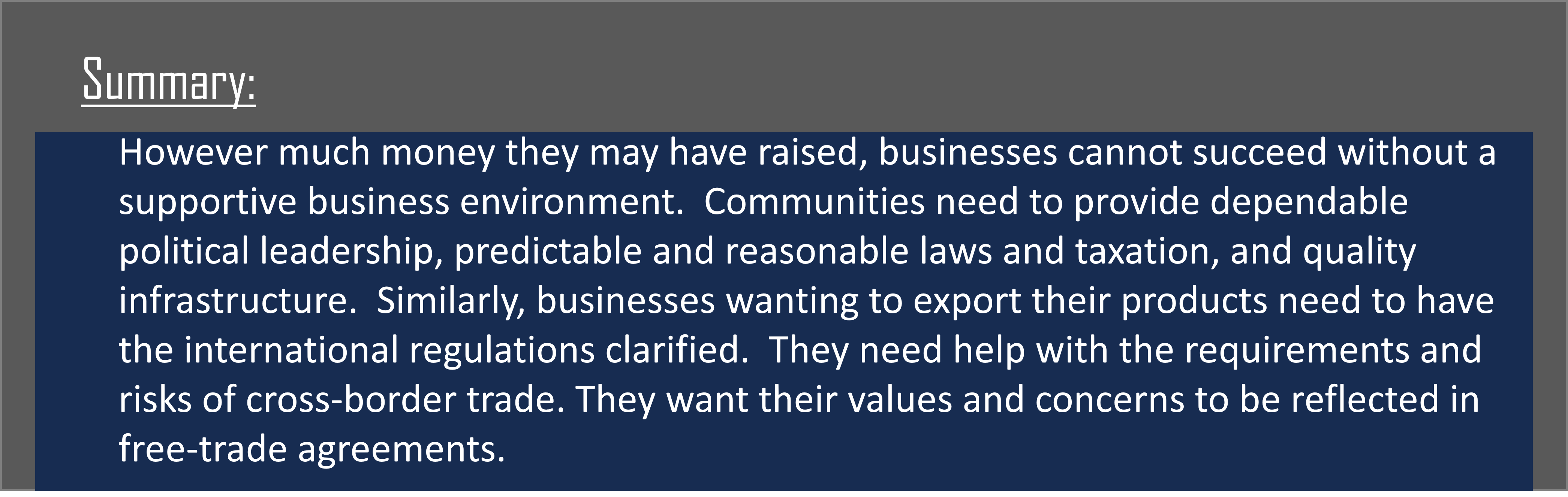

Public Safety Canada provides funding to support police services in cooperation with federal and provincial/territorial governments, but this funding may not be sufficient.

Perhaps a regional approach would be more affordable: the Mohawks of the Bay of Quinte, for example, might team up with Curve Lake, Alderville, and Hiawatha First Nations not too far away. A regional force would present a more detached and anonymous face to a community, deflecting angry push-back against bylaw officers and police chiefs from band members who take arrests and fines personally.

Gladue Courts:

At present, Indigenous police forces do not have their own courts. However, there are the “Indigenous Peoples’ Courts” or “Gladue Courts”. These statutory courts have full jurisdiction over Canadian law.

Gladue courts specialize in applying the principle affirmed by R. v. Gladue (1999), a principle incumbent on all courts in Canada, that judges should consider a person’s Aboriginal identity when sentencing. Judges should be aware that, because of systemic factors, Indigenous people are more likely to appear in court.[9] They should also honour the Indigenous tradition of restorative justice, attempting to find alternatives to imprisonment of an offender.

![Gladue Courthouse in Wagmatcook First Nation. Members of the court team and First Nations leaders gather in the new courtroom in Wagmatcook on the first day of operations (April 4, 2018) Credits to: Provincial Courts of Nova Scotia/Wagmatcook First Nation. Used with permission from: Wagmatcook First Nation [173]](https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/sites/1088/2021/04/uyntbrvfecd.jpg)

There are currently fifteen Gladue Courts, five of which are located in Toronto. The Gladue Court in Thunder Bay serves the Nishnawbe Aski Police Service region. There are also four national restorative justice programs, and dozens more at the provincial or territorial level.

We have seen that laws, leadership, reasonable taxation and quality infrastructure make a community a better place to live and a better place to do business. What about international business?

International Business

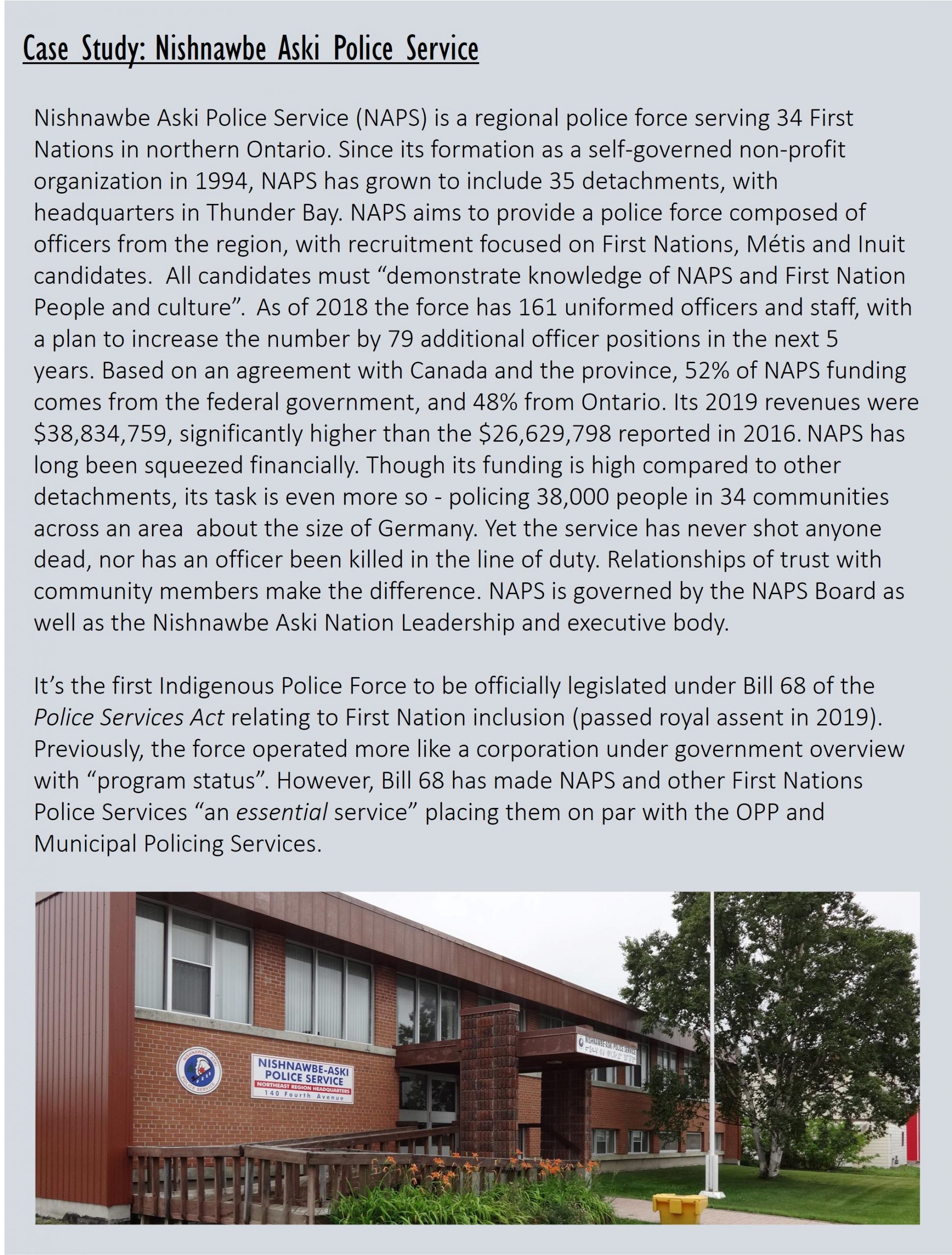

As the graphic below shows, Indigenous businesses are active in transnational trade.

It was has been natural for First Nations and Metis in Canada to do business with Americans; in the centuries preceding European contact and right up to the American Revolutionary War, the current Canada: US border was irrelevant. Many First Nations in particular aligned themselves with kin in territories on both sides of today’s border.

After the American Revolutionary War, Britian was worried about losing access to fur in the United States. Conseuqently Jay’s Treaty (1795) between Britain and the United States was signed, It allows for Indigenous people to travel freely across the US:Canada border and to bring items with them duty-free.

However, while the United States continues to allow people of at least 50% Indigenous ancestry to cross the border from Canada to live and work in the US, Canada no longer reciprocates. Neither country allows commercial goods to cross duty-free anymore. The Supreme Court has backed this position on the basis of legal technicalities.

The 2022 National Indigenous Economic Strategy for Canada (NIEDB et al., #104) calls on Canada to implement Jay’s Treaty. Its provisions would give Indigenous businesses an advantage over non-Indigenous businesses in importing and exporting, but it is an advantage that was promised to them after their interests were otherwise ignored during the American Revolutionary War and the subsequent creation of the Canada:US border.

Until Jay’s Treaty rights are restored, Indigenous leaders would like to see the creation of Indigenous free-trade zones, which are geographic areas where commerce can take place without import or export tariffs being charged.

A free-trade zone already exists by default at the Akwesasne Mohawk reserve on the Canada:US border near Cornwall, Ontario. Members of the community there has threatened to fight for their right to bring American products like cigarettes into Canada, and the federal government has closed its customs office on the reserve. Prior to this, the government’s attempt to collect tariffs drove much of the trade underground, and criminal organizations developed which bring drugs, firearms, and people across the border.

NAFTA, CUSMA, and other trade agreements have had little to say about Indigenous peoples. The National Indigenous Economic Strategy calls for that to change. Free trade agreements could include provisions regarding Indigenous Peoples and Indigenous businesses, negotiated in consultation with Indigenous leaders (#107). This could exceptions allowing governments to reserve some procurement contracts for Indigenous businesses. Free trade agreements could also prioritize Indigenous peoples’ environmental and conservation concerns.

The Strategy also calls for the creation of an Indigenous Export Development Corporation, like Export Development Canada (EDC). EDC provides insurance against cancelled contracts, provides guarantees sought by international partners, gives guidance for managing exchange rate risks, and offers loans and partnerships.

In our next chapter we will look at the economies of remote communities, where trade outside the community is expensive.

- Tulo (2014) Chapter 2. ↵

- https://www.tulo.ca/textbook ↵

- Fiscal Realities Economists (1999) ↵

- “Transparent” means that the information is publicly available and easy to understand. ↵

- National Indigenous Economic Development Board (2019), Annex A, Table 23. ↵

- Tulo (2014), pp. 120-2 ↵

- See for example this video of an intoxicated man being hit by an RCMP vehicle https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yanXOlXNw5s ↵

- Group discussion with author and students ↵

- Public Safety Canada (2020) ↵

Bylaws are laws a community or corporation develops for itself. They are not imposed by a higher level of government.