The Modern Treaty Era

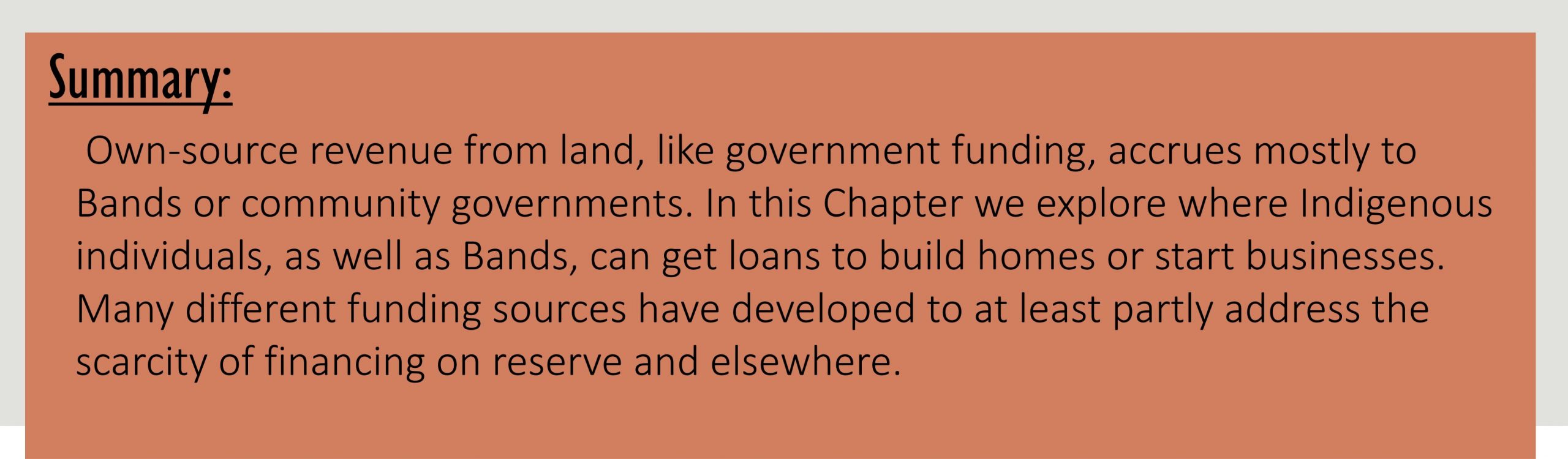

We have just discussed land ownership and the revenues that can be earned through environmental services, tourism, and resource extraction. Other potential sources of own-source revenue (OSR) come from interest on trust funds and savings, leases, property taxes and fees, and business profits.

As you may have noticed in this pie chart from Chapter 16, own-source revenue contributes 36% of revenue for the average First Nation; most of this is from the oil and gas earnings accruing to a minority of First Nations.

As the diagram below indicates, Indigenous businesses are an important engine for the Indigenous economy and the overall economy, primarily because businesses can become a source of funds – to the Band or other government as taxpayers, to the public as donors and employers, and to themselves as they fund their own expansions. Additionally, the savings of businesses and their employees give banks new funds for lending.

Another critical feature of business is that it exists to recognize and meet current consumer needs, identifying them with a level of accuracy and detail not possible for government. In the course of their operations, businesses create goods and services which were not previously available so conveniently or affordably.

![Financial Flow to and from Business. Flow built by: Anya Hageman, Graphic design by: Pauline Galoustian [168]](https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/sites/1088/2021/04/pkn-jhvgfcxd.jpg)

Businesses also enhance the productive capacity of a community by training employees, providing expertise, improving lands, providing products which are inputs for other firms, buying the products of local firms to use as inputs, providing scrutiny and criticism of governments, and adding to the case for improved infrastructure in the community. In short, they may provide a variety of backward linkages and forward linkages.

Indigenous Business Generally:

According to reportage in the Spring 2019 edition of Corporate Knights, Indigenous business represents about 1.4% of the Canadian economy. This falls short of the number it should represent if it were proportional to population, but is still quite an accomplishment considering the history. Indigenous business comprises about 45,000 firms generating 30 billion dollars.

The Corporate Knights estimate roughly agrees with the Canadian Council for Aboriginal Business’s 2020 estimate of 50,000 Indigenous-owned businesses generating 12 billion dollars annually. Among Ontario Indigenous-owned businesses, more than half are unincorporated and have no employees; yet two-thirds of these mostly small businesses have sales over $100,000[1].

In terms of businesses located within Indigenous communities, in 2017 there were “over 19,000 businesses located in Indigenous communities (17,000 on First Nations territory and 2,000 on Inuit lands) generating over $10 billion in revenue”[2].

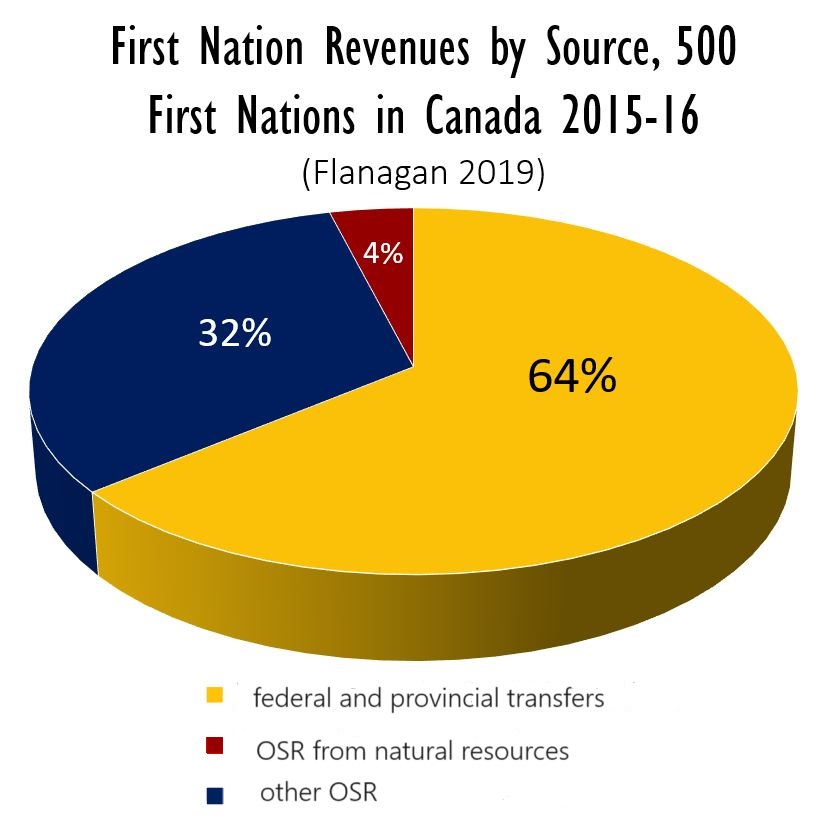

The Canadian Council for Aboriginal Business’ 2016 Aboriginal Business Survey indicated that, for 68% of Indigenous business owners, attracting or finding qualified employees is the biggest challenge. For 31% of Indigenous business owners, the most pressing challenge is finding money. In this Chapter we focus on finding the money needed to start and run a business.

Sources of Money for Indigenous Businesses

Only a small fraction of the lending available to Canadians is currently loaned to Indigenous businesses. In 2013, First Nations and Inuit businesses were accessing only one-tenth of the money that the average Canadian business was able to access [3].

1. Own Savings

On a field trip to Tyendinaga Mohawk Territory in 2019, the author was startled to learn that the community’s largest cannabis retailer had funded his lab and his shop using his own personal savings. This is common. Since reserve or remote homes and land are not attractive as collateral, and because income and population on reserves is low, reserve-based businesses have difficulty getting loans form commercial banks. Even in cities, loans may be difficult to secure because Indigenous people are less likely to own their own home or have paid off as much of their home as are non-Indigenous people. Other issues include low rates of financial literacy and lack of credit history. (NIEDB et al. 2022 p. 83).

2. Financing from the Band or Community

As shown in the diagram above, a community’s own revenues can be used to fund businesses run by the community or individual community members. These revenues can come from a Band’s own-source revenues or from federal or provincial grants not tied to particular purposes such as education or health care.

Bands have a fair amount of experience lending to Band members for home construction or home purchase, as discussed in Chapter 24. If the member defaults, the Band can take the house, which it no doubt can use for other Band members. It’s less likely the Band could use a defunct business, so we haven’t seen much business lending by the Band to Band members. Business loans are considered much riskier than housing loans.

Indigenous communities can organize investment pools, with different community organizations contributing money to the pool. The interest earned by the pool can be used each year to fund particular projects. When the principal is paid back, the money can be loaned out again. In many cases the federal government has contributed to the establishment of these funds. For larger loans, the government prefers to work with Aboriginal Financial Institutions.

3. Aboriginal Financial Institutions (AFIs)

Beginning in the late 1980s Indigenous leaders, the Native Economic Development Program, and the federal government cooperated to create various lending institutions focused on Indigenous businesses. One important second-generation AFI is the First Nations Bank of Canada.

Based in Saskatoon, the First Nations Bank of Canada (est. 1996) is the first federally chartered bank majority-owned and operated by Indigenous Canadians. It began in collaboration with Toronto Dominion Bank. By 2022 it had twenty physical locations, most in remote areas; the most northerly is in Pond Inlet on Baffin Island. Five branches are on reserves. FNBC has many ATMs across Canada, usually hosted by local community credit unions.

FNBC offers chequing and savings accounts, US dollar accounts, RRSPs and term deposits, mortgages, other loans and credit cards, online and smartphone banking, trust services, and business planning tools. In 2023 it announced plans to expand into wealth management, helping wealthy clients, or clients who have received large financial settlements to compensate them for past harms, to invest funds safely and profitably.

Taking a look at its 2020 annual report, we learn that FNBC had $46.3 million of equity and almost a billion dollars of assets. Of the assets, more than 300 million was business loans and about 100 million was mortgage loans. (Loans are assets because the borrowers have to return the money to the Bank, and because they generate interest income for the bank.)

Government Funding for AFIs

Originally, the federal government provided $240 million dollars to be shared among the various AFIs for lending to clients. This amount has turned over many times: over 45,000 loans have been made, totaling 2.5 billion dollars.[4]. There are currently over 50 AFIs, and they are represented by the National Aboriginal Capital Corporations Association (NACCA).

NIEDB et al. (2022) reports that as of 2015/2016, just under 95% of the loans had been successfully repaid, meaning that 5.2% had had to be written off.

In 2019 the federal government provided an extra $150 million in funds for an Indigenous Growth Fund to be managed by NACCA. Interest and principal will be paid back to any private lenders who contribute to the fund. In June 2022 the fund attracted its first investor, Block Inc. Block’s investment of $3 million was small compared to what the federal government provided, but it is a start. It seems likely that commercial banks and other agencies will want to offer investments in the Indigenous Growth Fund to “Impact Investors [5].

The 2022 National Indigenous Economic Strategy for Canada (NIEDB et al. #91) calls on the government to offer tax incentives for private sector and social investors.

It also calls for the government to invest further in Aboriginal Financial Institutions and give them the opportunity to distribute stimulus funds (#92) and for the creation of an Indigenous Business Development Bank (#93) like the Business Development Bank of Canada, a bank “devoted to entrepreneurs”.

Separate from the National Aboriginal Capital Corporations Association (NACCA), the Canadian Council for Aboriginal Business (CCAB) is a major non-government, nonprofit organization formed in 1982 to help finance Indigenous enterprises.

CCAB focuses on connecting businesses which are least 51% Indigenous owned and operated to private non-Indigenous creditors. It supports day-to-day operational, financial, and managerial support for smaller startup Indigenous businesses, unlike the federal government which is more focused on large-scale industry and community enterprises.

CCAB conducts independent research projects, for example the 2016 National Aboriginal Business Survey mentioned earlier. This survey found that the average Indigenous business’s money came 65% through personal savings, 19% through business loans/bank credits, 14% through Aboriginal Financial Institutions (AFIs), 10% through personal loans/bank credits, and only 9% through federal grants and loans.

In addition, the survey found that 51% of business owners found it difficult to locate external sources of funding, and 45% found that it was difficult to meet the qualifications for borrowing.

4. The First Nations Finance Authority (FNFA)

The First Nations Finance Authority is an entity which borrows in the money market on behalf of First Nations. (It does not raise money for individual First Nation members.) Its bonds are purchased by life insurance companies, central banks, provincial governments, some Canadian commercial banks, and large companies.[6]

The Finance Authority’s good credit ratings are due to several things. One is the implicit backing of the federal government, which has offered a token amount, $30 million, to temporarily offset any revenue shortfalls. Another is the fact that the Finance Authority has the authority to commandeer not only the collateral (being the predicted revenue streams) of any First Nation that cannot repay its loans, but also the fiscal governance of said Nation. Moreover, every participating First Nation must regularly repay interest and principal into a “sinking fund”. Another safeguard is that the Finance Authority only lends out 95% of the money it has borrowed on behalf of participating First Nations.

The First Nation Financial Authority came into being in 2006 via the First Nation Financial Management Act (FNFMA). This Act has three components to set First Nations up for financial success:

-

- The First Nation Tax Commission to help a First Nation develop a tax program for its community. It is hoped that the stream of future tax revenues can be used by Bands as collateral.

- The First Nations Financial Management Board to train First Nations in financial management, and, after having them set up fiscal checks and balances, certify them as being financially responsible. As of January 2024, 63 First Nations had received full certification and 218 others were working towards this goal, according to the Financial Management Board’s website.

- The First Nations Financial Authority (FNFA) to use the expected revenue streams of participating First Nations as collateral to get long-term loans. The FNFA charges fees to member Nations.

The First Nations Finance Authority sold $250 million worth of 10-year bonds at 3.4% interest in June 2014, and in June 2017 sold $126 million worth of 11-year bonds at 3.05% interest.[7]

This borrowed money is used by member First Nations to do such things as repair and build houses, construct community buildings, fund green energy projects, and refinance existing, higher-interest loans. The First Nations Finance Authority helped Membertou First Nation finance its stake in Clearwater Seafoods.

5. Federal, Provincial or Territorial Lending Programs for Indigenous businesses

Besides funding AFIs and providing insurance for Band loans and the First Nations Finance Authority, the federal government lends to Indigenous-owned or Band-owned businesses directly.

In partial fulfilment of its stated goal to fund at least $1 billion of infrastructure for Indigenous communities, the federal government’s Canada Infrastructure Bank announced in November, 2023 that it would offer loans between $5 million and $100 million to Indigenous communities seeking to buy shares in companies working on their traditional territories.

The federal government also offers entrepreneurship loans and training, funding for innovation and research, legal and regulatory support, marketing and communications support, funding to promote economic development and development readiness on reserve, and funding for the Canadian Council of Aboriginal Business

The federal government also reserves 5% of its purchases (“procurement”) for Indigenous vendors/service providers, where possible.

Federal programs are focused almost exclusively on First Nations and Inuit communities, but some have become available to Métis businesses.

The Métis Nation of Ontario supports Métis businesses with training and access to affordable loans. However, Ontario Métis businesses must come to individual agreements with investors and business partners. This format is very similar across other provinces, meaning that Métis businesses are mostly excluded from being able to win large government contracts or become suppliers on a provincial scale.

Caveat:

Although the federal government offers many business assistance programs, the percentage of Indigenous businesses using such a program is only 43%. According to the 2016 Aboriginal Business Survey, 32% of Indigenous businesses were using government loans or grants, and 25% were using training and employment assistance programs. The survey pointed out that the bigger and more established companies, earning $100,000 or more in revenue per year, were the ones most likely to be using government programs. Larger companies are more likely to be able to handle the complex qualification requirements and procedures, and they are the ones able to fulfill government procurement contracts.

6. Commercial banks and other private-sector lending

Commercial banks have had a limited presence in small towns and reserves.

But even when banks are located nearby, Indigenous people may feel unwelcome, as mentioned in the 2022 National Indigenous Economic Strategy for Canada. The reason why is perfectly illustrated in the case of Maxwell Johnson, a Heiltsuk Nation man who was opening an account for his granddaughter at a Bank of Montreal branch in Vancouver in 2019. Staff were alarmed that the granddaughter’s Indian Status identification card number didn’t match a database, and by a recent deposit of $30,000 in Johnson’s account. They also thought that Johnson and his granddaughter looked more “South Asian” than First Nation. Suspecting fraud, they asked Johnson to wait and they called the police. After some time the police arrived. They arrested and handcuffed both Johnson and his twelve-year-old granddaughter. After Johnson’s son, who had been doing his own banking at the bank, contacted their First Nation’s Restorative Justice Department, Johnson and his granddaughter were released.

2019 research [8]commissioned by the Financial Consumer Agency of Canada found that racialized customers at Canada’s six largest banks were more likely to be offered overdraft protection, balance protection insurance, premium credit cards, and other products that they did not likely need. Bank staff were more likely to communicate unclearly.

Commercial banks have been reluctant to invest in Indigenous projects, especially projects located on reserves. This is because of the lack of collateral that Indigenous communities are able to offer, and because of uncertainties around land rights, service provision, fees, and regulations.

Since reserve land is not attractive as collateral to private lenders, First Nations and other Indigenous communities may offer expected streams of revenue as collateral to private sector lenders, as long as this revenue is not earmarked for particular programs such as health care. Undesignated federal or provincial transfers, money from Impact Benefit Agreements, and taxes and rents expected to be collected from leaseholders can be used as collateral.

In the case of Fort McKay First Nation and Mikisew First Nation, prosperous reserves in the vicinity of the Oil Sands, the Royal Bank of Canada was happy to issue and sell bonds on their behalf, helping them raise $545 million at 4.14% interest from the private sector.[9] The money was used to buy a 49% stake in an existing oil storage facility. Contracts for oil storage, cooling and mixing were already in place, virtually guaranteeing future revenues.

For communities which don’t have much in the way of expected revenue, Bridge Financing might be available. The bridge financing company offers temporary loans until a community qualifies for a loan from a conventional commercial bank such as the Royal Bank of Canada or the Bank of Montreal. The company lends the community more money than is needed for the project. The extra money is put in a separate account where it used to pay a high rate of interest to the company. Technically, the community is not paying any interest at all.

Once the project is up and running, a conventional bank becomes willing to lend to the community at a normal, moderate rate of interest. The community borrows enough money from the conventional bank to pay back what it borrowed from the bridge financing company, which was perhaps 10% more than it actually needed. It then repays the commercial bank loan, with interest, over time.

7. Microfinance

Microfinance is the provision of banking services to marginalized communities. There are two main forms of Microfinance: Credit Unions and Solidarity Lending.

Credit Unions:

Credit unions are cooperatives; they are member-owned and distribute all profits to their members. Clients who use the credit union’s banking services become members and receive dividends each year.

Historically, credit unions have provided financial services at lower cost and easier terms than conventional banks. DUCA Credit Union, formerly the Dutch Canadian Toronto Credit Union Ltd., helped author Hageman’s immigrant parents buy their first house in 1973.

There are already credit unions as far north as Puvirnituk, Quebec and Pickle Lake, Ontario. Perhaps credit unions can be encouraged to move further north and to other underserviced areas. As we shall detail in Chapter 29, retail and other cooperatives are widespread in Canada’s Far North. Attention should be paid to adding financial cooperatives to the existing mix.

Many Nations, an Indigenous-owned financial cooperative providing insurance, employee benefits, and pensions to Indigenous organizations across Canada, is based in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan.

Solidarity Lending:

In recent decades, a new wave of lending in developing countries using something called “Solidarity Lending” has become synonymous with Microfinance. In 2006, Dr. Muhammad Yunus and the Grameen (“Village”) Bank he founded in Bangladesh were awarded a Nobel Peace Prize for their Solidarity Lending.

Solidarity Lending works by lending money to individuals, each of whom belongs to a group of borrowers. The group members support each others’ economic achievements. If a member has difficulty repaying a loan, the rest of the group assists and/or pressures the member to make the payments. A group’s reputation and cohesion serves as collateral. The credit-worthiness of the entire group is at stake if one of its member fails to repay a loan.

Using Solidarity Lending, the Grameen Bank and its many followers lend small amounts of money to people who have no collateral and therefore no access to traditional banks. They may cooperate with intermediary organizations who recruit, vet, and instruct the would-be borrowers.

To see Solidarity Lending in action, go to kiva.org.

Solidarity Lending has not found a foothold in Canada. According to Frankiewicz (2001), this may be because of the high costs of doing business in Canada, the intense competitiveness of business, the low population density, and the availability of social assistance.

8. Social Development Bonds

Social Development Bonds, Social Impact Bonds, or Development Impact Bonds are a very new kind of financial instrument. There are four parties involved: the investor, the implementer, the evaluator, and the donor.

Here’s how it works: the investor gives money to the implementer for a program, by buying the implementer’s social development bond. After a set period of time, an evaluator judges whether the program has been successful. If the program has been successful, the donor pays the investor the face value of the bond, plus interest. If it has not been successful, the donor pays nothing or some fraction of the face value of the bond, so that the investor makes a negative rate of return on the investment.

“Restoring the Sacred Bond” is a program funded by a social development bond in August 2019. The program is run by the Manitoba Indigenous Doula Initiative and offers high-risk Indigenous mothers the support of doulas, people trained in prenatal, birth delivery, and post-natal care of mothers and infants.[10]

If the program results in babies spending 25 fewer days in foster care during their first year of life, compared to what might have been expected without the program, the program will be judged a success. Then the Manitoba government will repay the investors with interest.

The eight investors, which include the Children’s Aid Foundation of Canada and the Winnipeg Community Foundation, together paid 2.6 million dollars for the bond. The bond was organized and marketed by the MaRS network.[11]

Another example is a bond issued by Raven Capital Partners in Vancouver. In 2021, Raven Capital Partners was looking for investors willing to buy this bond, which finances diabetes reductions in six First Nations communities. The federal government was offering to pay a return of 5-9 percent, depending on results.

One advantage of social development bonds is that the implementer can access funding without having its work micromanaged by the donor, which is often a government agency. The implementer is free to innovate to meet the program objectives. The donor, meanwhile, is protected from having to pay for a program that is unsuccessful.

9. Angel Investors

Social Development Bonds work because there are donors willing to pay for the good social results. Government agencies often fill this role, as well as the role of investor in the social development bond. The investor is taking an above-average risk by buying the bond.

“Angel investors” provide loans or buy stocks and bonds for the impact their money will have, not to chase the highest possible financial return.

All over the world, people are lending to family members and friends. People are choosing fossil-free and ESG funds. Perhaps Indigenous funds will soon be added to the mix.

Raven Capital, which organized the diabetes bond mentioned above, takes an equity share in small Indigenous businesses; investors in Raven should be aware that small businesses will always be risky; high returns are not guaranteed.

RISE (risehelps.ca), funded by philanthropists, offers mentorship plus small loans at low interest rates to small business owners who have struggled with mental health, addiction, or intergenerational trauma.

Having explored many ways that Indigenous businesses can raise money, we turn to Chapter 28 to consider the other things businesses need.

- CCAB (2020) ↵

- Haaris and Alasia (2019) ↵

- NAEDB (Sept. 2017) ↵

- NACCA website, downloaded August 2019. https://nacca.ca/about/ ↵

- Impact investors are less concerned about rates of return than about the environmental, social, and governance consequences of their investments. ↵

- based on 2021 correspondence with Ernie Daniels, then President and CEO of FNFA. ↵

- Onoszko (2017). ↵

- FCAC (2022) ↵

- Onoszko (2017). ↵

- Onoszko (2017) ↵

- Jagelewski (2019). ↵

Money earned by the Band, for example from Band-owned businesses, from taxation, from leasing land to non-Band members, and from Impact Benefit Agreements.

Backward linkages, or upstream linkages, refer to the impact of an economic activity on suppliers of inputs, workers, communities, and environments.

Forward linkages, or downstream linkages, refer to the usefulness of an economic activity in providing materials, skills, and services for new products and economic activities.

The term "fiscal" is used to discuss the government's spending or tax revenue, the two key components of a government's budget.