The Modern Treaty Era

Indigenous communities have many reasons to claim ancestral lands. The land may have significant spiritual and cultural value. Its location may provide better opportunities for ceremonies, recreation, education, or business. Finally, the land itself can provide income or business opportunities.

Preserving Land for its Own Sake

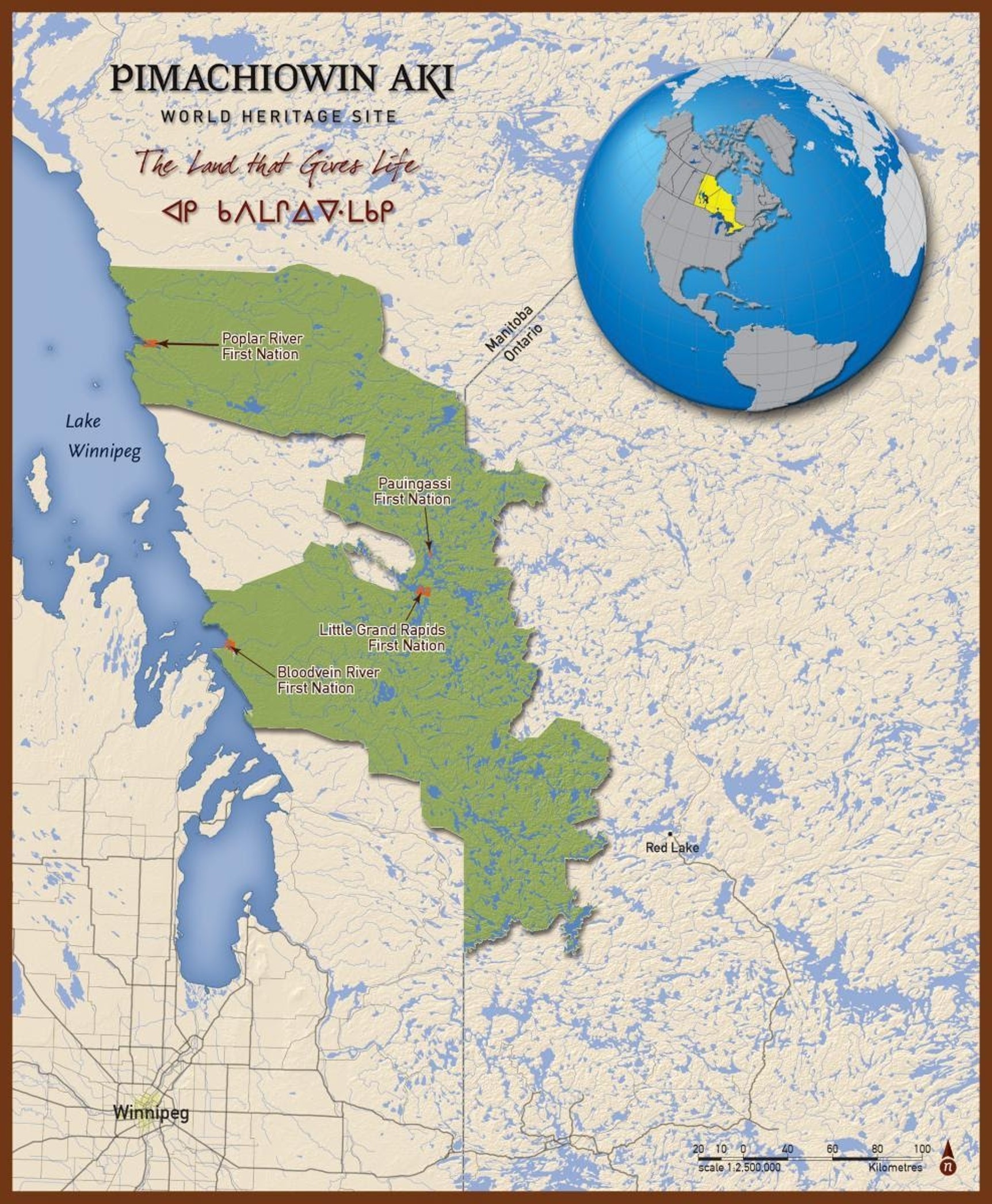

There are many examples of Indigenous communities acquiring land rights not to use the land for business purposes but to protect it from commercial exploitation. One example is that of four Ojibwa communities close to the Manitoba-Ontario border. Concerned about a proposed electric grid to be built through their traditional territory, the First Nations – Bloodvein River, Little Grand Rapids, Pauingassi, and Poplar River – joined together to nominate it for UNESCO World Heritage Site status. The federal and provincial governments came on board to support this effort. In July 2018 UNESCO approved the bid, effectively protecting an area the size of Vancouver Island from commercial development. The process took 16 years and cost the First Nations about six hundred thousand dollars; the governments of Ontario and Manitoba paid about five million.

The newly protected area is named Pimachiowin Aki, which means “the land that gives life” in Anishinaabemowin. Pimachiowin Aki is just one of many newly protected Indigenous lands which will help Canada meet its target of having 30% of Canadian lands and water under conservation by 2030. Another example is Qat’muk, consisting of the Jumbo Valley in British Columbia and adjacent watersheds. The Ktunaxa are partnering with the Nature Conservancy of Canada to have Qat’muk declared an IPCA (Indigenous Protected and Conserved Area). For more on protecting lands with Indigenous cooperation, go to https://conservation-reconciliation.ca

In another example of conservation, the Innu of Ekuanitshit and the municipality of Minganie in Quebec declared the Magpie River to be a legal person with 1) the right to flow; 2) the right to cycle between periods of high flow and low flow; 3) the right to evolve naturally; 4) the right to maintain its natural biodiversity; 5) the right to fulfil its essential functions within its ecosystem; 6) the right to maintain its integrity; 7) the right to be safe from pollution; 8) the right to regenerate and be restored; and 9) the right to sue.[1]

This was the first time in Canada that a natural feature was declared a person. The strength of its personal rights have not yet been tested in a lawsuit.[2]

Earning income from the Management of Protected Lands

Conservation lands can be income-generating, if Indigenous peoples are paid for their insights or stewardship of the land, or if they can offer eco-tourism of some kind.

The federal Impact Assessment Act (2019) concerns the environmental research and reporting that must be done whenever major public works projects are considered. The Act allows for some of this work to be done by Indigenous governments, presumably for compensation.

Muller (1975) suggested that Indigenous communities could be given the right to collect tolls on roads in exchange for their responsibility to monitor traffic, watch for fire, patrol drunk or other problem drivers, and assist stranded motorists.

Nuxalk knowledge keepers have been patrolling the mouth of the Bella Coola River in BC as volunteer “Guardian Watchmen”. They take note of illegal hunters and fishers, boaters in distress, and rogue grizzly bears. It would make sense for this very real service to be compensated. Such compensation would not be new. Recall that Cree monitored the beaver reserves set up in the 1930s. Today, Cree in the Moose River area are employed to monitor goose hunting. Inuit are being paid to collect polar bear scat and provide information on the bears and their habitat in the BEARWATCH program.

The 2022 National Indigenous Economic Stategy calls on government to affirm Indigenous rights as stewards and protectors of lands, especially publicly-owned lands. (NIEDP et al, Call #48). It also calls for the hiring of Indigenous companies to clean up contaminated areas (#54).

One approach to conservation is to pay local communities for the number of animals or plants which are preserved, instead of banning hunting and then searching for and punishing poachers. Community Based Resource Management could give nearby communities the right to profit from the existence of the species of concern, polar bears for example.

The community would be able to hunt the bears for personal use or sale or make money by allowing others to hunt the bears. The government would pay the community each year for the number of polar bears in its vicinity, on behalf of Canadians who value the polar bears’ continuing existence.

The local community now would have a clear interest in growing the polar bear population, discouraging poachers, and finding ways to identify and isolate problem bears. In Community Based Resource Management, locals are given the property rights to an animal population rather than to a parcel of land. It would probably be even more efficient to give rights to both land and animals to the local Indigenous community, since habitat is critical to the animals, and animals can provide revenue with which to improve and protect habitat.

In Community Based Resource Management, locals are given the property rights to an animal population rather than to a parcel of land. It would probably be even more efficient to give rights to both land and animals to the local Indigenous community, since habitat is critical to the animals, and animals can provide revenue with which to improve and protect habitat.

The Case of Wood Buffalo National Park:

The history of Wood Buffalo National Park serves as an example of what can go wrong when the local community is not included in conservation. Wood Buffalo National Park, which is about the size of Switzerland, straddles Alberta and the North West Territories.

As described by Indigenous Circle of Experts (2018), this park was established in 1922 on Treaty 8 land used by the Mikisew Cree, with the understanding that the Cree would be able to harvest the bison once the population of bison was safely established, and that the land would be returned to the Cree in 100 years. Any guesses as to what happened?

Not only does it appear that the land will not be returned, not only were the bison kept off-limits to the Mikisew, but also the hunting, trapping and fishing activities of the Mikisew were limited or prohibited depending on the species. Mikisew who broke the new laws were fined, incarcerated, or banished from the park. Many left the area.

Because of limits on traditional food-gathering activities, migration away from the area, and environmental degradation, valuable knowledge of the species living in the park has been lost.

Moreover, the biodiversity of the Park has been affected by two projects outside the park: the Bennet Dam (opened 1968), with the attendant problems related to damming described in Chapter 15; and the Athabasca Oil Sands development.

“To show them how we used to do our trapping and hunting, and where, —where we used to pick rat root, pick up eggs, when the birds come out in the spring, annual egg picking—we can’t do that anymore. We can’t teach anybody these things because we don’t have the birds that used to lay the eggs, or most of the animals we used to hunt. It’s the same with trapping, you know. There is very little left that you can pass on to the younger generation. I take my grandkids down the river and all I can say is ‘This is what used to be there.’” ICE (2018) p.30

The people most sensitive to the Park’s well-being, whose activities were an integral part of the Park’s ecological balance, were kept out.

A program of Community Based Resource Management, on the other hand, would have involved the local Indigenous community in monitoring species, maintaining trails and nesting areas, reforestation, setting hunting quotas, selling hunting licenses, supervising hunting and fishing, and guiding tourists and hunters.

Income Possibility: Clean Energy

The Spring 2019 edition of Corporate Knights, published by the Globe and Mail, noted that in the next five years, 175 northern communities – presumably mostly Indigenous – would be transitioning away from using diesel-fueled generators for the community’s electricity. This represents an opportunity to invest in clean energy projects. Energy and other “utilities” represent infrastructure that is constantly used and generates reliable revenues from mostly predictable costs. According to Corporate Knights, clean energy projects generate returns of 10% or more.

Already, about 20% of Canada’s green energy production comes from installations that have Indigenous ownership, usually about 25% ownership. This includes 152 installations generating at least 1 megawatt per hour at peak.

Income Possibility: Natural Resources

We have just discussed the possible benefits to Indigenous peoples of managing wild lands for conservation or energy collection purposes. What about commercial use of wild lands? For many Indigenous peoples living in remote areas, ventures like forestry, mining, petroleum, and hydroelectricity projects offer an obvious way to earn income.

Hunting and Trapping:

Hunting and Trapping is regulated at the provincial or territorial level. Indigenous communities with self-government agreements have worked out arrangements with the province or territory to regulate hunting and trapping on their own lands.

During the time of treaty making, First Nations understood themselves to have the right to hunt, trap and fish on any unoccupied lands within their traditional territories. However, these rights were greatly restricted during the early nineteenth century, when Indian Agents could prevent people from leaving reserves, and when the Indian Act contained clauses prohibiting the sale of meat and hides.

In response to Indigenous activism, a series of Supreme Court rulings affirming Aboriginal Rights, beginning with R. v. Calder in 1973, have led gradually to increased freedom for First Nations to hunt, trap, and fish on their traditional territories. The R v. Powley decision in 2003 extended these privileges to Métis, simultaneously establishing the legal definition of Métis.

First Nations reserves are typically too small for any hunting or trapping to take place, but today, Status Indians have the right to hunt and trap off reserve on unoccupied lands within their Treaty’s boundaries. If they wish to hunt or trap in another Treaty area, they can present a letter of permission from a First Nation within that territory, called a Shipman letter.[3]

However, since hunting meat to sell to others has been deemed not to be a traditional activity, First Nations and Métis hunters do not have the right to sell their meat. They do have the right to sell fur but may have to abide by provincial or territorial limits on method of trapping and number and type of pelts collected.

Muller (1975) recommended subsidizing fur trappers the way that provincial governments subsidize dairy farmers.

“This would protect employment, prevent the loss of specialized knowledge, provide connection to elders and to the land, and possibly restore ecological balance.”

This piece of advice has been acted upon: in certain regions hunter and trapper support programs do exist, financed by provincial governments or local Indigenous governments.

Fisheries:

In Canada, the federal government regulates saltwater fisheries and salmon fisheries, while the provincial and territorial governments regulate the freshwater fisheries within their own borders. Self-governing Indigenous communities with modern treaties have agreements with federal and provincial governments about how to use the fisheries within their territories.

Historically, Indigenous people have been crowded out of fishing opportunities. Treaties usually implicitly or explicitly guaranteed Indigenous people the right to fish on unoccupied lands within the treaty area, but over time, settlers took over more and more of the fisheries. The suppression of Indigenous fishing in Georgian Bay and Lake Huron is well-documented in “The Fishing Chiefs”, a 2018 television documentary, part of the Bruce Documentary Series.

In response to Indigenous activism, Supreme Court Rulings such as R. v. Sparrow (1990) have restored the right to fish – within an Aboriginal community’s traditional territory.

“An Aboriginal person who is not a member of the treaty group can no more participate in a treaty fishery without permission than a non-Aboriginal person can,” explains Professor Hamar Foster of the University of Victoria.[4]

The Aboriginal right to fish does not include the right to sell fish commercially, unless that Aboriginal community has negotiated an agreement with the government, has negotiated a side agreement to its Treaty, or has a court ruling determining that commercial fishing is part of their community’s traditional practice.

The Heiltsuk in British Columbia have such a ruling (R. v. Gladstone), and on that basis they and seven other nations have won the right to fish commercially for several species, “close to home in mid-sized and small vessels.”[5]. In Atlantic Canada, the Mi’kmaq, Wolastoqiyik (Maliseet) and Peskotomuhkati (Passamaquoddy) have the right to earn a “moderate livelihood” from fishing (R. v. Marshall).

Without such a ruling or a legal agreement with the Crown, Indigenous fishers who want to sell fish must obtain a fishing license from the Crown.

In the spirit of the United Nations’ Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, the federal government’s Department of Fisheries and Oceans has created a “Reconciliation Strategy” listing dozens of actions to be taken. These actions can be summarized as involving Indigenous knowledge keepers and communities in fisheries decision-making and management, and increasing Indigenous participation in the industry by training and hiring Indigenous people. The federal government has also secured fishing licenses and quota for Indigenous groups. For example, in 2022 the government announced that, through its Pacific Integrated Commercial Fisheries Initiative, it would

- help A-Tlegay Fisheries LP purchase herring seine net licenses

- purchase sablefish quota for Salish Seas Fisheries LP

- help Nuu-chah-nulth Seafood purchase canning equipment

- help T’Sou-ke First Nation purchase oyster aquaculture equipment

among a total of 52 projects costing 11.8 million dollars.

Provincial and territorial governments may also have such programs. British Columbia partners with the federal government to support Indigenous firms to conserve fish habitat through its BCSRIF program.

The National Indigenous Fisheries Institute is an Indigenous-led organization that promotes best practices in fisheries management.

Forestry:

Seventy percent of Indigenous communities are located in forested areas.[6] Indigenous people have long worked in forestry; in 2011, nine thousand did.[7]

Rolf Knight (1978) tells the story of a steam-powered sawmill set up by the Hudson’s Bay Company on Vancouver Island in 1856. Local Indigenous men cut trees by hand to bring to the sawmill and were paid one HBC blanket for eight large logs or 16 small ones. He describes the expansion of the forestry sector in British Columbia and how Indigenous men and women were migrating to the sawmills around Victoria by the 1870s. Indigenous “longshoremen” acquired an excellent reputation for loading and unloading boats. “Both they and employers recounted tales of the unusual skill, stamina, and knack of Indian crews.” (Knight p. 126). These longshoremen were instrumental in unionizing dock workers. Some Indigenous communities bought their own sawmills, for example the Gitxsan at Kispiox in 1898, who issued shares to Band members to fund the purchase.

On the other hand, some communities were discouraged from buying sawmills, for example the Mississauga at Hiawatha First Nation (Ontario), whose plans to build a sawmill that same year were thwarted by an Indian Agent who was annoyed that the Band had not asked permission first.[8]

In British Columbia, “a steady alienation of the most accessible and valuable Crown timber land to sawmills and speculators, at give-away prices, occurred in the two decades before 1900,”writes Knight (p. 262). This is what had been going on in the eastern provinces earlier. During the twentieth century, logging licenses were granted or sold to non-Indigenous people on traditional Indigenous lands, while First Nations might be fined for logging without a license. These injustices prompted Indigenous activism and legal challenges.

Over the last forty years, Supreme Court rulings around treaty rights and Aboriginal title have gradually enhanced the ability of First Nations and Métis to regulate logging on their traditional territories and to manage their own forestry operations. It was a dispute about logging on ancestral Haida lands that led to the Supreme Court ruling Haida Nation v. BC (2004), establishing the Duty to Consult.

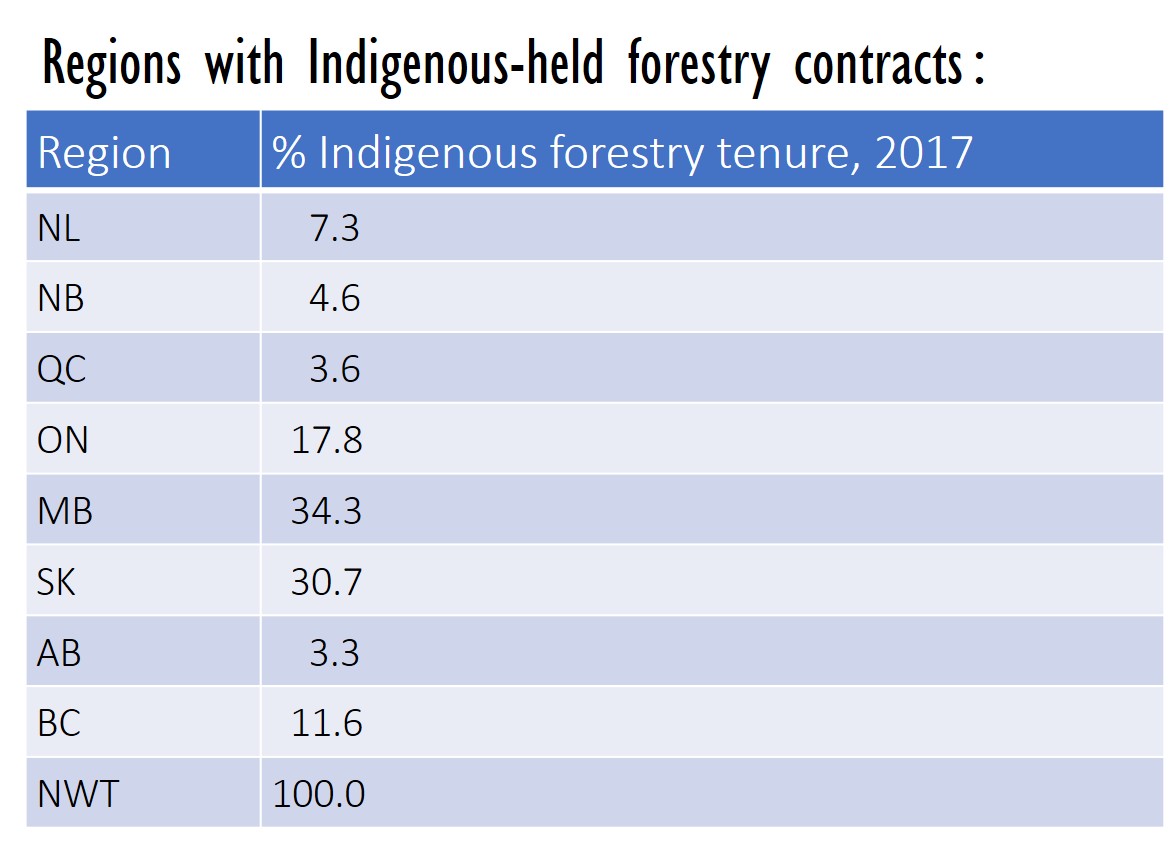

In the early 1980s, only half a percent of the forest available to be harvested was Indigenous-owned, but by 2017 the number was 10.5%.[9]

Since 2011 the Indigenous Forestry Initiative, paid for by the federal Department of Natural Resources, has helped fund Indigenous forestry projects, though not at the level of the individual entrepreneur. Other branches of federal and provincial government have also assisted. Over the period between 2017 and 2020, in partnership with Indigenous Services Canada, the IFI has granted over $12.7 in funding for forestry ventures.[10]

In the Table above we see the Indigenous share of forestry tenure. Forestry tenure is the forested area for which the Crown has issued licenses or other permissions.

The Huu-ay-aht First Nations on the west coast of Vancouver Island, who have a modern treaty, are partners with Western Forest Products in a forestry business called Tsawak-qin Forestry Limited Partnership. About forty band members are directly employed in forestry. [11]. Tsawak-qin is striving to exceed the province’s 2021 protections for old-growth forests while attempting to build up its business..

The National Aboriginal Forestry Association (NAFA) exists to promote and support Indigenous forestry that is holistic and fosters sustainable Indigenous communities. NAFA collaborates with governments, forestry industry associations, academic institutions and other groups.

Forestry Revenue Sharing

The province of Ontario now has an Resource Revenue Sharing(RRS) program for forestry. The province collects stumpage fees, a tax per cubic meter of wood charged to forestry companies for the privilege of logging on Crown land. As of 2018, Ontario shares 45% of stumpage fees with First Nations of Treaty #3, First Nations of the Wabun Council, and Cree Nations on the west side of James Bay.

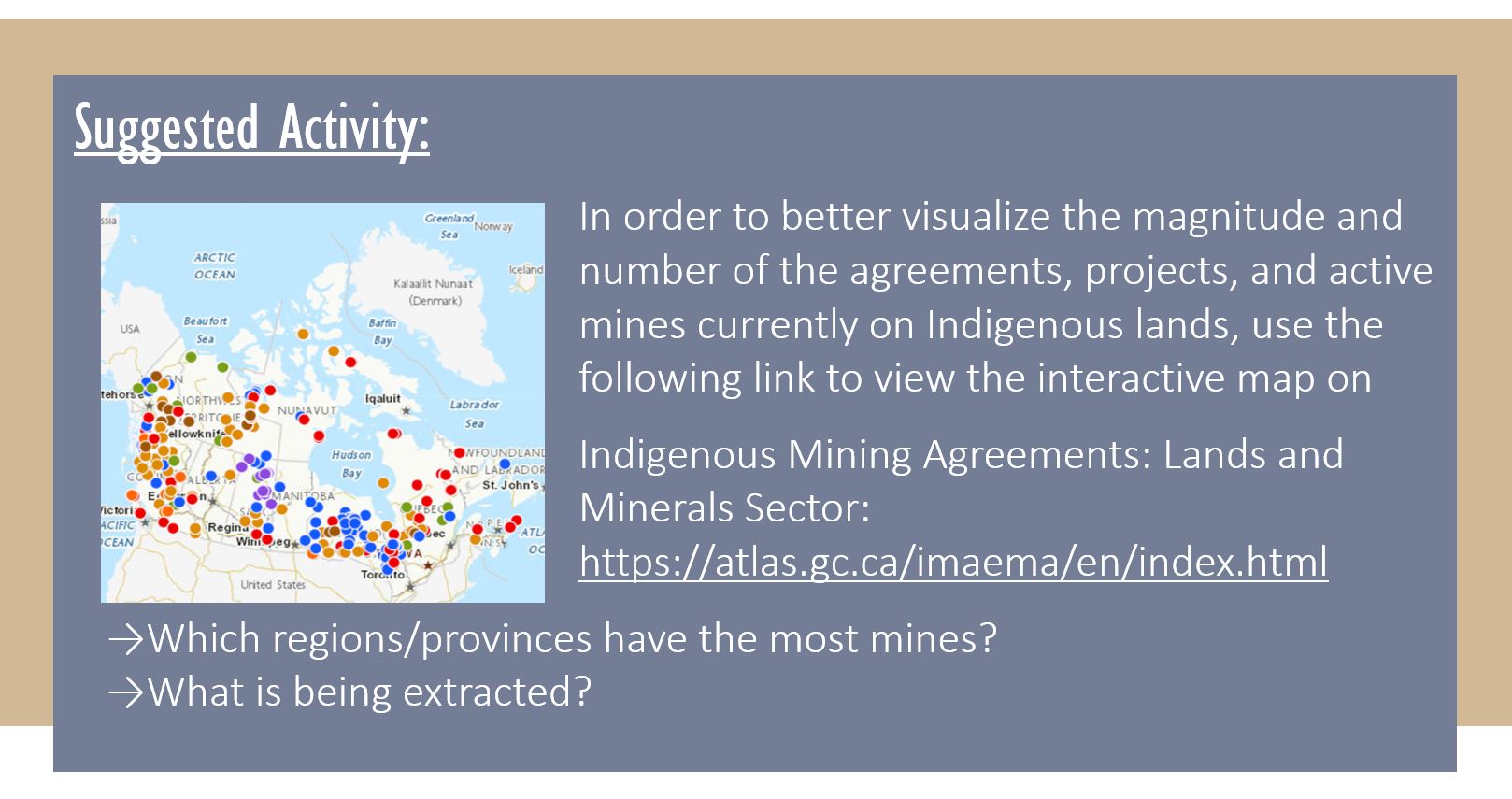

Minerals:

![Copper Mining in Canada. Photo credits to: Gord McKenna (CC BY-NC 2.0) [164]](https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/sites/1088/2021/03/5608019388_6ba51600ec_o-1.jpg)

Since 1930, provinces and territories have owned and regulated all subsurface resources. However, First Nations believe that, when they agreed to the Numbered Treaties, they were allowing settlers to use the land only “to the depth of the plow”. At that time, no one was imagining that Prairie lands would be rich in potash, uranium, or oil. Settlers eventually mined and drilled on ceded land without compensating First Nations.

All over present-day Canada, First Nations were pushed off lands that were mineral-rich, for example during the Klondike Gold Rush (1897). The Klondike Gold Rush precipitated Treaty 8, which also does not include subsurface mineral rights for First Nations, nor any revenue sharing.

For more than 100 years there was no sharing of mining profits with Indigenous people in Canada. While Sudbury, Ontario became world famous for its nickel, the local First Nations continued to receive just $4 a year per person.

Ontario now has a program to share its mining revenue with local First Nations. , just as it is doing with forestry revenue. Beginning in 2018, Ontario will share 40% of the income taxes and royalties it collects from mining companies working existing mines, and 45% of its revenues from new mines, with First Nations of Treaty #3, First Nations of the Wabun Council, and Cree Nations on the west side of James Bay. (Royalties are an extraction-based tax paid by resource companies to the government).

Since 2011, British Columbia has implemented some mining revenue sharing agreements, called Economic and Community Development Agreements, with First Nations living in the vicinity of new or expanding mines. First Nations receive 2% of net revenues initially; then, once certain fixed costs have been paid off, 13% of net revenues. (NIEDB et al., 2022).

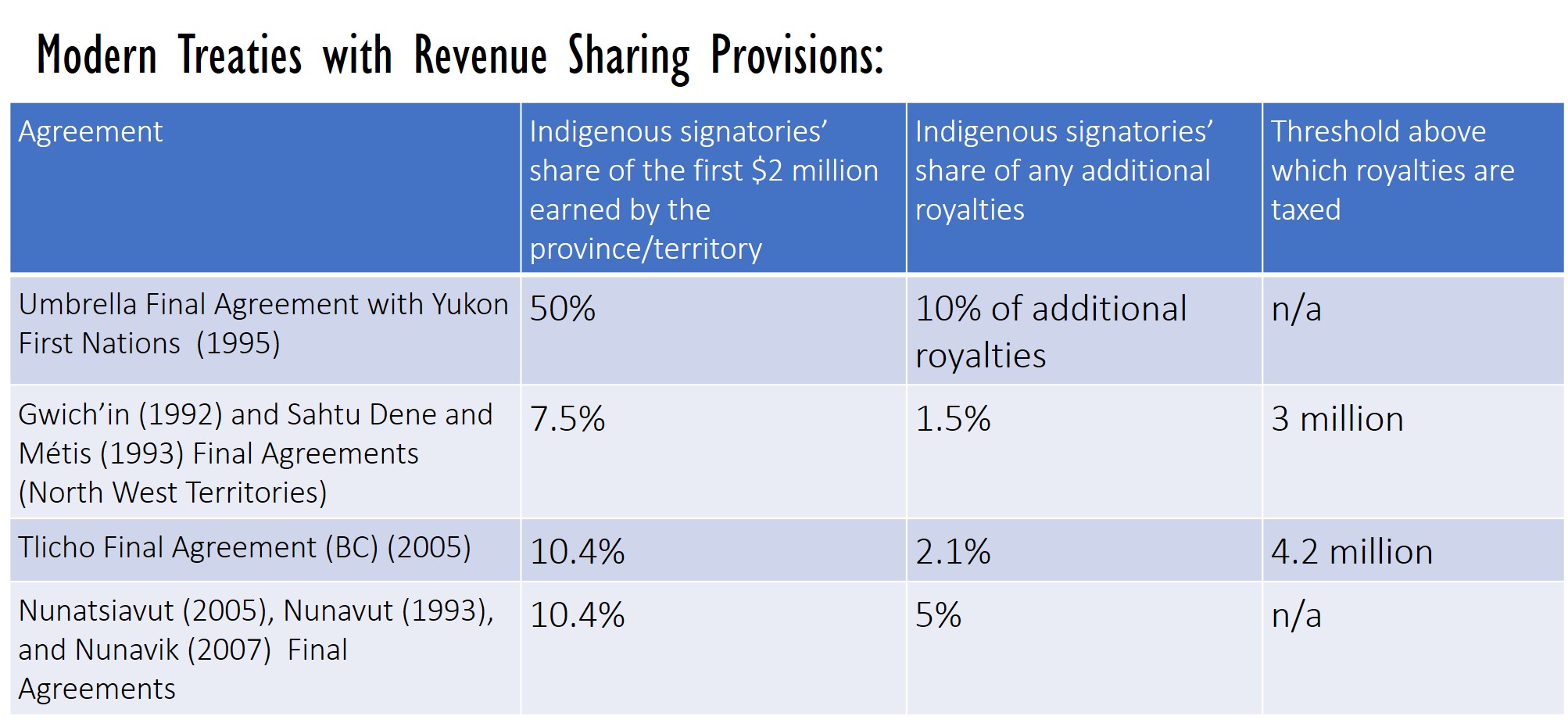

Modern Treaties typically contain provisions for revenue sharing from mining. Some of these are shown in this table from Coates (2015):

Oil and Gas development on reserve lands is regulated by the 1985 Indian Oil and Gas Act. A First Nation’s share of revenues from an oil and gas project, resulting from its ownership of the project or from an Impact Benefit Agreement, is deposited in the Indian Moneys Trust Fund with the federal government. Bands must apply to withdraw this money.

Under the Indian Oil and Gas Act, the Minister of Indigenous Services has the right to regulate oil and gas exploration, the terms of oil and gas extraction contracts, the determination of royalties, the amounts extracted, and environmental precautions, and also has the right to inspect facilities and operations for compliance with the Act.

The Indian Resource Council (IRC) represents more than 130 First Nations who produce oil and gas or who directly benefit from oil and gas production.

In an advertisement in The Globe and Mail June 20, 2020, the IRC asked for financial support from the federal government due to declining sales of gas during the COVID-19 pandemic.

It noted that together, member First Nations had made 256 million dollars a year at the market’s peak (presumably meaning 2018), and that they depend on these oil and gas earnings to fund programs and services on reserve.

The IRC appealed to Canada’s fiduciary duty toward oil and gas producing First Nations, a duty that arises from the fact that Indigenous Services Canada and its agency, Indian Oil and Gas Canada, manage First Nations’ business and money. It stated that the federal government’s management of First Nations’ oil and gas has left First Nations “extremely vulnerable to market turbulence.” How might this be?

Opposition to Pipelines

First Nations have not typically objected to oil and gas projects on their traditional territories, but many have objected to pipelines passing through their territories. The reasons are environmental but also strategic: the more one complains, the more compensation one may receive. The protests often divide Indigenous communities and pit some Bands against others.

The First Nations LNG Alliance is a group of First Nations who want liquefied natural gas (LNG) infrastructure on their traditional territories. As of 2023 it included nine First Nations in British Columbia, one in Saskatchewan, and one in Newfoundland and Labrador. One of the BC First Nations, Wet’suwet’en Nation, is divided; its elected Chief and Council are in favour, but its hereditary Chiefs are not.

In 2023 the Alliance was promoting the completion of the controversial Coastal Gaslink pipeline running from Shell’s fracking operation in northeast British Columbia to the coastal town of Kitimat, BC. Sixteen First Nations along the route have the option to (jointly) purchase a 10% stake in the business once the pipeline begins its operations. The Alliance was also in favour of the construction of a facility at Kitimat to cool and liquefy the gas, co-owned by the Haisla Nation and Pembina Pipeline Corporation. The facility would run on electricity generated by local hydroelectric projects. A Shell export terminal would store the gas. The Haisla Nation would provide battery-powered tugboats to assist with docking.

Impact Benefit Agreements

Impact Benefit Agreements are normally negotiated when a non-Indigenous company seeks to extract resources on lands claimed by an Indigenous community. These agreements can mitigate the downsides of resource extraction by guaranteeing hiring and training of Band members, use of Band businesses to provide services like food, accommodation, and trucking, investment in the Indigenous community, and environmental cleanup.

Impact Benefit Agreements have not usually, but could include the provision that the company will share profits with the Indigenous community.

Existing shareholders would likely object to giving the Indigenous community an equity share of the company, but sharing profits does not rise to that level.

At the time of writing this text, companies must report payments over $100,000 made to First Nations, but not the details of any Impact Benefit Agreements, and First Nations do not have to label Impact Benefit Agreement revenues as such in their financial reporting[12].

Companies often ask communities to sign non-disclosure agreements. They do not want the details of the IBA known.

Unfortunately, Indigenous groups are at somewhat of a disadvantage in bargaining unless they spend a great deal of money on legal, engineering, and environmental experts.

IBAs are costly to negotiate and can vary wildly from one community/industry partnership to the next. We might conceive of an umbrella organization, representing Indigenous interests, to craft a set of best-practice principles and guidelines for Impact Benefit Agreements.

Resource Revenue Sharing (RRS)

We referred earlier to Ontario’s new practice of sharing mining royalties and stumpage fees with local First nations. Indigenous communities may prefer this to having to negotiate Impact Benefit Agreements on their own.

Flanagan (2019) cautions that money earned from revenue sharing should be tied as much as possible to a Band’s own lands and decision making, so as to encourage Bands to take the initiative to promote economic activity on their lands. He figures that “increased resource revenue will be associated with a higher [Community Well-Being Index score] to the extent it makes the First Nation an active partner in the enterprise through management, investment, ownership, and job creation.”

The Resource Curse

Nations which are well-endowed with natural resources have not always grown as quickly or offered as high a standard of living to their citizens as nations which lack natural resources. The term Resource Curse has been used to describe some of the reasons why that may be.

Flanagan (2019) writes that not many First Nations which earn royalties from oil and gas have high CWB scores. Flanagan believes this is because the mining is often managed by Indian Oil and Gas Canada, a top-down approach that does not stimulate as much entrepreneurship at the band level.

Hillel (2019) compares reserve and non-reserve communities in Alberta between 2006 and 2016. She finds that communities which had oil or mining agreements in the vicinity experienced more rapid growth in median earnings and in an index of well-being for 2006 which she created.

However, the fraction of the working age population employed in the primary sector was negatively correlated with earnings growth and wellbeing, a “resource employment curse”, even after accounting for the negative correlation between resource employment and educational achievement. A depressing effect of resource abundance on educational attainment is one possible driver of the Resource Curse.

Parlee (2005), citing Bowlby (2005), suggested that Alberta’s relatively low rate of high school completion was related to the availability of resource jobs for youths without a high school diploma. However, in 2016 Alberta had the highest rate of high school completion in the West and the second-highest rate in the country.

Another driver of the Resource Curse is that resource companies are vulnerable to major swings in the price of what they sell. They typically have decades of boom and bust. This can be very destabilizing. There are many ghost towns in Canada’s north.

Resource companies often come from elsewhere and hire people from elsewhere. The resource is often exported in raw form. Thus, there are not many backward or forward linkages, making resource staples perform poorly in terms of delivering economic development.

In Canada’s north, companies have usually been owned by southern Canadians or Americans. Companies from elsewhere are not as invested in the local environment. They may think little of leaving tailings ponds and stumps behind when the business is ended. In Alberta and Saskatchewan in 2020 there were more than 10,000 abandoned oil wells for which there was no known owner who could afford to perform the needed closure and environmental clean-up.[13].

Local hiring has been limited, though this is rapidly changing due to the improved bargaining power of First Nations and Inuit since the Duty to Consult was established.

Sometimes companies have neglected to hire locals because the companies are not familiar with local norms. They may not understand the importance of taking several days off for funerals. They may not understand that a Christmas break might not be as important to locals as the spring goose hunt. They may judge people with records for drug possession or domestic violence as not suited for employment.

Many of the men (for it has been mostly men) that are hired are from away. Right from the time of the first fur traders, the non-Indigenous men who show up in Indigenous communities are adventurous young-to-middle-aged men. Speaking frankly, and generalizing wildly, these concentrations of younger men have tended to leave behind a lot of empty beer bottles and single mothers, rather than amateur orchestras and vegan recipes.

The same could be said even of many tourists who visit the North. In 1975, Hugo Muller, the quotable former HBC employee and Anglican priest, writing to a non-Indigenous readership, urged:

“Look into the average station wagon of the tourist (American or Canadian) which is parked somewhere on a northern main street. Half of it is filled with fishing gear. The other half with beer or liquor. Surely our civilization [sic] has better things to bring than beer. The only kind of entertainment our [sic] native peoples are familiar with is the local hotel – generally the worst hotel in town…The reading material one finds in construction camps – the cheap pornography – finds its way into Indian homes.”

Recently, Indigenous voices have been heard speaking forcefully against so-called “man camps” and linking them to missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls. The 2018 documentary film Nuuca tells the story of the Fort Berthold reservation in North Dakota, correlating the oil and gas fracking boom with an increase in sexual violence. A letter by a member of the O-Pipon-Na-Piwin Cree Nation, circulated by Amnesty International in April 2020, called on Manitoba Hydro to close the Keeyask Dam construction camp because of danger of harassment and sexual violence.

“When you’re walking around in your community and there’s men driving around looking for a woman, it’s scary. I wouldn’t send my grandchild to work there because it’s not safe.” – Cree elder from northern Manitoba[14]

A resource company in a small town has a big impact, with its employees possibly doubling the population. Not only that, but as the largest employer in town, the company has the power to influence the going wage, and the power to offer workers less than the value of their marginal product.

Another aspect of the Resource Curse is political problems. One political problem that you find in resource-rich regions is that governments in a sense buy the loyalty of citizens by providing perks like:

- no consumption taxes (Alberta)

- cheap gasoline (Venezuela)

- cheques to help with living expenses (Saudi Arabia)

Consequently, citizens are less motivated to get involved in politics, less interested in holding the government to account for its spending decisions. This gives the government more scope to be incompetent or corrupt.

On reserves, Chief and Council are allowed to spend money not designated for service delivery on “per capita distributions”. Money from band-owned businesses, from resource extraction, or from land claims settlements can be used in this way. Per capita distributions are gifts of money, no strings attached, equal in size for each member of the community. Per capita distributions are very popular and can be used to sway voters.

Wolf Collar (2020) warns that per capita distributions are often used for spending on consumer goods sold outside the community, and that a significant amount is spent on drugs and alcohol. The money could be better used by a Band in housing or job creation. He would like to see children’s per capita distributions held in trust until they reach twenty-one years of age. In Miawpukek First Nation, children’s distributions are held in trust until age 19.

Interviews with Miawpukek band members in 2010 indicated a need for young people to receive advice about investments prior to receiving their trust funds. Many young people were pressured by family to hand over the money, and were having to deal with fake friends hoping to share the wealth.[15]

Corruption is the second political problem. When there is money to be made from the Nation’s resources, expect politicians to try to get a cut. Expect attempts to manipulate elections, even attempts to bully rivals, by politicians wanting power.

As Indigenous communities secure land title to resource-rich lands and seek to develop these lands, and as they secure revenue-sharing agreements for use of their traditional lands, Indigenous communities need to have strong governance structures in place, such as we discussed in Chapter 19, so as to minimize corruption and social tension, and to maximize the prudent management of these resources.

Various papers, such as “Institutions and the Resource Curse” by Mehlum, Moene, and Torvik (2006), have shown that countries with better institutions benefit from having abundant natural resources, whereas countries with poorer institutions are worse off for having abundant natural resources.

Good Stewardship of Resource Earnings

Good institutions are needed so that the natural resources are extracted responsibly, and the profits used wisely. Here are three pieces of advice that will help any community steward its resource advantages.

- Harvest renewable resources sustainably, so as not to deplete the stock. Mathematical modeling can help you estimate the optimal sustainable yield, which depends on prices, costs and the interest rate, as well as on the biology and ecology. Of course, random events like weather can throw things off, so do not depend too much on any estimate.

- Extract non-renewables like minerals and oil at the optimal rate, which depends on the interest rate and present and future prices and costs, as well as the price at which no one would buy your product any longer. Again, precision is impossible because of unpredictable changes in these parameters.

- Save part of your profits from non-renewable resources for the day they are depleted or become uneconomical to mine any further. Re-invest those savings in another form of capital like infrastructure or education. Then, when the mine or oil well closes, the community can earn income from the other capital. This is known as Hartwick’s Rule. One Indigenous community that successfully followed Hartwick’s rule is Samson Cree First Nation, which built up a trust fund of more than 450 million dollars during the years its oil production was high.[16]

A fund built up by resource earnings can be a useful source of loans to new or expanding businesses. Business finance is the subject of our next chapter.

- Stuart-Ulin (2021) ↵

- Balsalm (2021). ↵

- White, (2017). ↵

- First Nations Study Program (2009). ↵

- Heiltsuk Chief Councillor Marilyn Slett, quoted in Bennet (2021) ↵

- Government of Canada (2016b). ↵

- Ibid, (2016). ↵

- Shpunisarsky et al., 2016. ↵

- Bickis (2019). ↵

- Government of Canada, (2020d). ↵

- Stueck (2022) ↵

- Flanagan (2019) ↵

- Parliamentary Budget Officer (Jan. 2022) ↵

- In Amnesty International, (2020). ↵

- Orr (2013). ↵

- Flanagan (2019). ↵

Provincial governments tax resource extracting companies doing business in the provinces, and the federal government taxes resource-extracting companies doing business on Crown land in the Yukon, Northwest Territories, or Nunavut. RRS occurs when these non-Indigenous governments share resource tax revenues with the Indigenous groups claiming the land on which the extraction is taking place.