The Modern Treaty Era

We know that land is important for so many reasons. Looking at Land from a traditional Indigenous point of view, we would never consider it just an economic asset. But in this Chapter we’ll focus on land’s economic significance.

Economist André Le Dressay (2016 p.265) has proposed two main strategies for First Nations to become independent of government transfers. That is not to say that, in the meantime, government transfers are not necessary to lift people and communities out of crisis and to build their capacity for economic growth. But looking beyond that stage, Indigenous economies can grow by Strategy #1: expanding the land to which they hold legally established rights and expanding their rights over that land. Strategy #2 is to adopt laws and practices that promote business on those lands. These laws and practices can reflect the values of the community and its desire to develop in a holistic way; communities can adopt adopt a form of “community capitalism” where decisions are made at the community level rather than at the individual level (Flanagan 2019). Generalizing, we can write: This echoes what we learned about Economic growth. Economic growth can be generated by increased inputs, more efficient use of inputs, and more specialization and trade.

This echoes what we learned about Economic growth. Economic growth can be generated by increased inputs, more efficient use of inputs, and more specialization and trade. This last formulation is better. It’s not just land that matters: Indigenous economies can expand by increasing their labour force, improving the health, knowledge, education, skills, and experience of their members, adopting new technologies, and improving access to markets for example.

This last formulation is better. It’s not just land that matters: Indigenous economies can expand by increasing their labour force, improving the health, knowledge, education, skills, and experience of their members, adopting new technologies, and improving access to markets for example.

But in this chapter, we will focus on land.

When we think of the restoration of land to Indigenous peoples, we may think of their historic, cultural and emotional ties to the land, and of the justice in righting past wrongs. However, restoration of the land has economic significance as well. Land is an important form of capital, potentially generating income into the indefinite future.

One of the greatest impositions of the reserve system and the Indian Act is the way it has limited the land base of Indigenous peoples, and the way it has limited their ability to capitalize that reserve land.

As you know, First Nations were reduced to small reserves which would never grow in size no matter how quickly the band might grow.[1]

Furthermore, the protections against creditors found in the Indian Act, meaning that no person who is not a member of the band can seize reserve land if a band member defaults on a loan, render reserve land almost useless as collateral. Most Canadians are able to secure mortgages to buy houses or get loans to start businesses only because the bank can claim and then sell their house and property should they default on their loan.

Because creditors cannot claim reserve land, and also because reserve land is subject to regulations which are opaque and variable, reserve land is not attractive to creditors and cannot be used as collateral. This is an issue not only for Indigenous people in Canada but for less privileged people throughout the world.

However, giving creditors the ability to seize land belonging to Indigenous people creates problems of its own. We say that reserve land is “alienated” once it becomes owned by people who are not members of that Indigenous community. How much alienation of land could an Indigenous community incur before it lost its sense of identity and ability to shape its future according to its values? We return to this question at the end of the chapter.

Economist Hernando de Soto wrote an insightful book called The Mystery of Capital: Why Capitalism triumphs in the West and fails everywhere else (2003).

De Soto argued that the root cause of poverty in much of the world is the inability of the poor to leverage their land, talent, and savings into new investments. They cannot translate their capital into business opportunities because of a lack of certifications and rights. They have no title to the land they use, no personal identification documents such as a birth certificate, and often, no relationship with a bank.

Even in Canada, a lack of personal identifying documents prevents some people from participating in the larger economy. Without two pieces of photo identification, one cannot open a bank account. Without a credit card, one cannot rent a car, reserve a hotel room, or possibly even acquire a cellphone plan.

Clio Straram, Senior Regional Manager, Indigenous Banking at Toronto Dominion Bank in 2020, identified lack of identification, as well as lack of reliable and fast internet, as factors limiting the ability of First Nation individuals to open bank accounts and acquire loans.[2] Many people on reserve do not have or need driver’s licenses to operate vehicles. Many misplace and lose their birth certificates and Status cards. Straram envisions that these documents be stored in the Cloud and be accessible by cellphone.

To translate land into useful capital that generates income, documentation that outlines property rights must accompany the land.

What do Fully-Formed Property Rights Look like?

A property right to land is complete when it gives the owner the following rights:

- The right to use the land as the owner pleases, and to earn income from the land

- The right to exclude others from using the land

- The right to improve the land as the owner pleases

- The right to give, lease, or sell the land to anyone else

In Canada, most people living off-reserve own their land as “fee simple”. Fee simple is very close to a complete land right. However, it is slightly constrained by the right of government to control the use of the land. It is also constrained by civil and criminal law. So, for example, even if you own your house and land, you are not allowed to turn it into a marijuana grow-op. And the government has the right to buy your house and land from you if it wants to run a highway through your property.

Land Rights Under the Indian Act

Under the Indian Act, reversionary title to reserve land belongs to the province or territory where the reserve is located, so that if anything were to happen to the band, the land would revert to the province’s ownership and management. The band, and members of the band, cannot sell reserve land to non-band members. They can only lease the land to non-band members. The band as a whole has the right to exclude others from the land and the right to use and improve the land as it wishes, subject to the articles of the Indian Act. Those articles specify selling land only to other band members, allowing the government to buy the land for public purposes, and following federal regulations which may have been created for reserves regarding mining, logging, wastewater treatment etc. For individual band members there are:

- Customary Allotment:

This is the informal arrangement whereby an individual or family occupies a parcel of land because they have done so for some time and the community recognizes the place as theirs. Customary Allotments entitle holders to use and improve the land as they wish, subject to regulations imposed by the Band Council, and to exclude others from the land.

Limitations:

- Unless these are formally recognized by the band through a Band Council Resolution (BCR), federal and provincial courts of law will not recognize customary allotments

- The Band Council can override these allotments at will, reducing the incentive to improve these properties

- the lack of certainty regarding future use of these lands further reduces their value as collateral

- the lack of a right to sell or bequeath these lands, even to family members, further reduces the incentive to improve these lands or accept them as collateral.

- Certificates of Possession:

CPs are the strongest property right possible for band members under the Indian Act. They are approved by the Band Council and by Indian Affairs and are upheld in Canadian courts. They give the owner the right to subdivide and sell the land to band members, bequeath the land to band members, and lease the land to off-reserve residents or corporations. A lease based on a certificate of possession is called a “locatee lease”.

In a regression analysis with Katrine Beauregard (2013), Flanagan found that reserves where many CPs had been issued had better housing quality, even after accounting for other factors such as remoteness. However, Aragón and Kessler (2020) found that CP intensity did not improve household income for band members. We will discuss their findings later in this chapter.

Limitations of CPs:

- Applying for a CP has taken as long as 11 years

- Land cannot be sold to a non-First Nation member of the community

- Land cannot be held by a member of the community who leaves the reserve for more than six months

- Some lands covered by CPs have been subdivided by inheritance dozens of times so that they are tiny and effectively useless (Flanagan 2019)

Note that CPs limit the amount of land the Band can use for social housing or leasing to businesses. A reserve may look as though it has enough land for new housing or business, but many of the convenient roadside lots may belong to Band members with CPs.

- Leases:

Anyone, band member or not, Status or not, Indigenous or not, can lease land belonging to a reserve once the majority of members in the First Nation vote to “conditionally surrender” or “designate” the land to the federal government for leasing purposes.

If the land is not designated, and an individual wishes to lease out their land on the reserve, both the Minister of Indigenous Affairs and the Band must approve the lease. The revenue stream expected from the leasing agreement can be used as collateral. About 3.5% of reserve land was leased in 2011 (Flanagan 2019).

Limitations:

- in the past, the fate of land designated for lease was unclear. Did it still belong to the Band?

- leases take longer to arrange than leases on land which is not part of a reserve

- leases are managed by the federal government, whose interests have not always appeared to coincide with those of the band

- the revenue from the leases does not go directly to the Band but is deposited in their account at the Indian Moneys Trust Fund

4. Permits

The Band can issue permits for non band-members (or band members) to use reserve land, without having officially designated the land for leasing purposes. As explained by Aragón and Kessler (2020), permits allow a limited, specific use of the land, like livestock grazing or crossing the property with a road or pipeline. They do not give the permit-holder exclusive access, and they are usually granted for shorter periods of time than is a typical lease.

Permits may be issued to anyone, band-member or not. The Band and the Minister of Indigenous Affairs both have to sign off on the permit.

Aragón and Kessler (2020) found that, for one time period where data was sufficient, the percentage of reserve land covered by leases and permits issued on behalf of the community was positively correlated with water quality, total spending, and the salary of the Chief, suggesting that these forms of land tenure were providing significant revenue to the community.

So, the four forms of land ownership on reserve –customary allotments, certificates of possession, leases, and permits –all suffer from limitations in concept or implementation. The authors of Building a Competitive First Nations Investment Climate (2014) write:

“There is little evidence that the Indian Act property right system was intended to support economic growth. In fact, there is historical evidence to suggest the purpose of the Indian Act property right system was to prevent economic growth. First, individual property rights were not granted to First Nations because they were not considered responsible enough to use it in their best interest. Second, the land management intent was to maintain First Nations as wards of the state. Third, the land registry system was not intended to facilitate transactions or provide security to investors.”

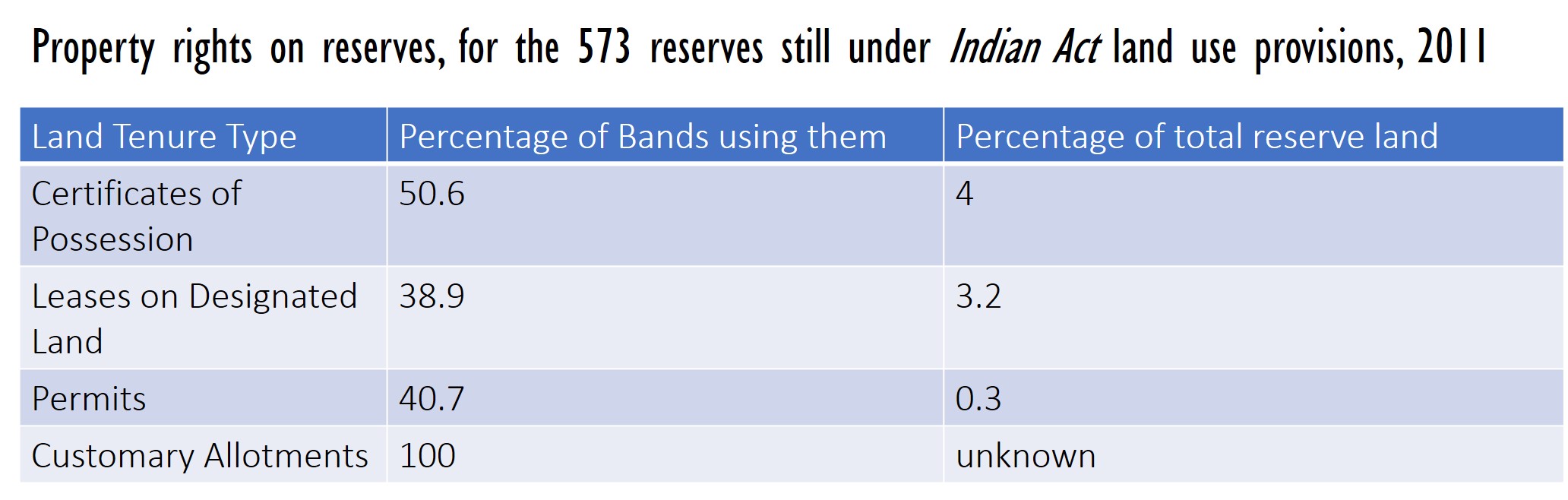

Not only do certificates of possession (CPs), leases, and permits have drawbacks, it is also the case that they are not much in use. As the Table below shows, in 2011 only four percent of reserve land was covered by CPs, among reserves still under Indian Act land use rules. Half of reserves did not have any CPs at all, and a majority had no lease and/or permit.

Creative Use of Certificates of Possession and Leases

Although CPs and leases offer incomplete property rights, they do offer some degree of property rights, and can be leveraged creatively to get commercial bank loans.

As we know, commercial banks are unlikely to be willing to accept a certificate of possession as collateral for a housing loan (mortgage); but they may be willing to lend to a Band member if the Band guarantees the loan. Many Bands guarantee their members’ mortgages if the member has a Certificate of Possession to offer as collateral. If the member defaults, the Band will assume ownership of the member’s Certificate of Possession.

In another formulation, a Band grants its member a Customary Allotment and offers its own expected revenues to a bank as collateral. The member pays 25% of the cost of the house they want to build and gets a mortgage from a bank for the remaining 75%. If the member defaults on the mortgage, the Band pays the bank, and the Band takes the member’s house and land.

Another creative idea is the “A-to-A lease”. In this case a band member leases their own land to themselves for a specified length of time, say 99 years. The band member uses the lease as collateral to get a mortgage from a commercial bank. Should the band member default, the bank will own the lease, and will be able to rent out the land for the remainder of the lease period. The title for the land stays with the First Nation. A commercial bank would probably not accept this arrangement unless the band member has a certificate of possession to the land being leased.

Remember that for a person to lease out their land they require the permission of the Band and of the federal government. Westbank First Nation, which has a self-government agreement, can avoid this red tape and is the only First Nation so far with an A-to-A leasing program.

Not all Bands dare to underwrite members’ housing loans. However, for Bands that do, their participation is in turn likely to be guaranteed under the federal government’s Ministerial Loan Guarantee program. Indigenous Services Canada can make itself liable for up to 2.2 billion dollars under this program and is currently liable for 1.82 billion. Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation, owned by the federal government, provides additional loan guarantees.

In our Housing chapter we found that the 2018 cost of 400 homes of mixed type ranged from 47 million in Eastern Canada to 64 million in the North. A mortgage might not be needed for the entire value of the home, so let’s use the lower number, 47 million, implying $117,500 per home. The 2.2 billion just identified would then cover roughly 19,000 homes, about one quarter the needed number.

The First Nations Market Housing Fund, established by the federal government with $300 million in 2007, also provides guarantees on Band-backed loans, for qualifying Bands. If Bands do not qualify, it trains the Band’s administration in best financial practices.

Alternatives to the Indian Act system of land rights

Since the property rights to reserve land under the Indian Act are limited, reducing the value of reserve land as collateral, and choking leasing arrangements with red tape and delays, First Nations leaders such as C.T. Manny Jules have spearheaded amendments to the Indian Act. These are championed by the Tulo Centre of Indigenous Economics in its online textbook and by Professor Tom Flanagan in his book Beyond the Indian Act: Restoring Aboriginal Property Rights (2011).

In particular, the First Nations Land Management Act (FNLMA) (1999) allows any First Nation, if interested, to develop its own land code. The First Nation will no longer need federal government approval to lease land or to designate land to particular individuals. Moneys earned from land will go directly to the Band without being deposited at the Indian Moneys Trust Fund.

The First Nations Land Management Board offers direction and templates for creating a land code and the accompanying regulations around land ownership rights, land ownership transfer, the land ownership registration system, land use regulations, and dispute resolution processes. The lands will be registered in the new federal First Nations Land Registry. A third party (not federal government, not First Nation) must approve the code, and the band members must agree to it. The federal government provides money for setting up the new system, and for future victims of fraud.

Under the new land code, legal documents can be issued to holders of customary allotments, which certify that the allotments cannot be annulled by the Band Council. Different kinds of land ownership and usage rights can be created, with one key exception: land cannot be held in fee simple. The provision of the Indian Act that forbids the possession of reserve land by non Band members remains in effect.

As of 2018, 78 First Nations had passed land codes and 53 more were in the process of so doing.[3]

Knauer (2010) studied forty First Nations, 8 of which had adopted a new land code, and 32 of which had not (four from the same province as each of the 8 adopters) and found that the adopters had statistically significant higher income, average earnings, and growth in available housing.

To help develop land codes, First Nations can make use of the First Nations Lands Advisory Board (1996+) and its First Nations Land Management Resource Centre (1999+).[4]

Limitations:

- The process is costly

- Each First Nation develops its own land code, making it difficult for businesses to anticipate the rules

- Fee simple property rights are not an option; provincial governments still have reversionary title

To ease these limitations, a First Nations Property Ownership Initiative was proposed in 2010, but it has proved to be politically infeasible. This initiative would have allowed participating First Nations to issue fee simple property rights to band members. There would have been a First Nations land registry, and a ready-to-use legal framework for property tax.

A First Nation interested in going this route would have had to hold a referendum showing band members how existing property rights would or would not be converted to fee simple. The provincial government would no longer have retained reversionary title to the land.

Disadvantages of Fee-Simple ownership:

Fee-simple land ownership brings with it its own issues. First, there is likely to be an increase in wealth inequality since people who already own certificates of possession are the ones most likely to be granted fee simple title, and they will experience an instant increase in the value of their land holdings.  Another issue with fee-simple land ownership is the “alienation” of reserve land through sale: If more and more land is sold to, or repossessed by, non-First Nation people, can the community’s culture and spirit survive? Note that the First Nation will still have regulation and taxation powers over that land, no matter to whom it is sold or transfered.

Another issue with fee-simple land ownership is the “alienation” of reserve land through sale: If more and more land is sold to, or repossessed by, non-First Nation people, can the community’s culture and spirit survive? Note that the First Nation will still have regulation and taxation powers over that land, no matter to whom it is sold or transfered. Relevant to this discussion, Aragón and Kessler (2020) found that the benefits of certificates of possession were going primarily to non-band members. They studied 103 First Nations bands which used CPs between 1991 and 2011. The results were disappointing. The percentage of reserve land covered by CPs was not positively correlated with household income for band members. Neither labour income nor social assistance income changed significantly. Rather, the percentage of reserve land covered by CPs was correlated with economic opportunities for non-Indigenous people. CPs were also correlated with the number of non-Indigenous people on reserve. The authors believe that wealthier outsiders were attracted to the reserve by the new land tenure arrangements. An inflow of wealthier residents would explain why CPs were correlated with an increase in housing construction and housing quality.

Relevant to this discussion, Aragón and Kessler (2020) found that the benefits of certificates of possession were going primarily to non-band members. They studied 103 First Nations bands which used CPs between 1991 and 2011. The results were disappointing. The percentage of reserve land covered by CPs was not positively correlated with household income for band members. Neither labour income nor social assistance income changed significantly. Rather, the percentage of reserve land covered by CPs was correlated with economic opportunities for non-Indigenous people. CPs were also correlated with the number of non-Indigenous people on reserve. The authors believe that wealthier outsiders were attracted to the reserve by the new land tenure arrangements. An inflow of wealthier residents would explain why CPs were correlated with an increase in housing construction and housing quality.

K. Pendakur and R. Pendakur (2021) found that subscribing to the First Nations Land Management Act prior to 2015 did not result in a First Nation or Inuit community having a higher average income than other First Nation or Inuit communities in 2016; however, income inequality within the community decreased by about 2% as measured by the Gini coefficient. This seems to be at odds with Aragón and Kessler’s report of wealthy newcomers. The newcomers must be a small minority. Pendakur and Pendakur (2017) also reported falling inequality, even as income increased much more for non-Indigenous than Indigenous within the same community.

Why are CPs not more strongly associated with rising incomes for Indigenous people? Aragón and Kessler caution that certificates of possession are still incomplete property rights compared to fee simple rights. They also point out that, even if reserve land could be fully “capitalized” – not that many Bands would desire this – translating this capital into rising household income would be hampered by the lack of business opportunities on reserve. We discuss how to create a positive business environment in Chapter 28.

In Chapter 27 we will explore some ways to help Indigenous people borrow despite the fact that their land may be unattractive as collateral. In the meantime, Chapter 25 describes how Indigenous communities have been able to add to their land base.

engagement with the mainstream economy as a group rather than as individuals

A mortgage is a loan issued to help someone buy a house or condominium.