The Modern Treaty Era

For millennia prior to European contact, during European settlement, and ever after, Indigenous people have been an indispensable part of Turtle Island’s labour force. They are needed more than ever as Canada’s labour force ages.

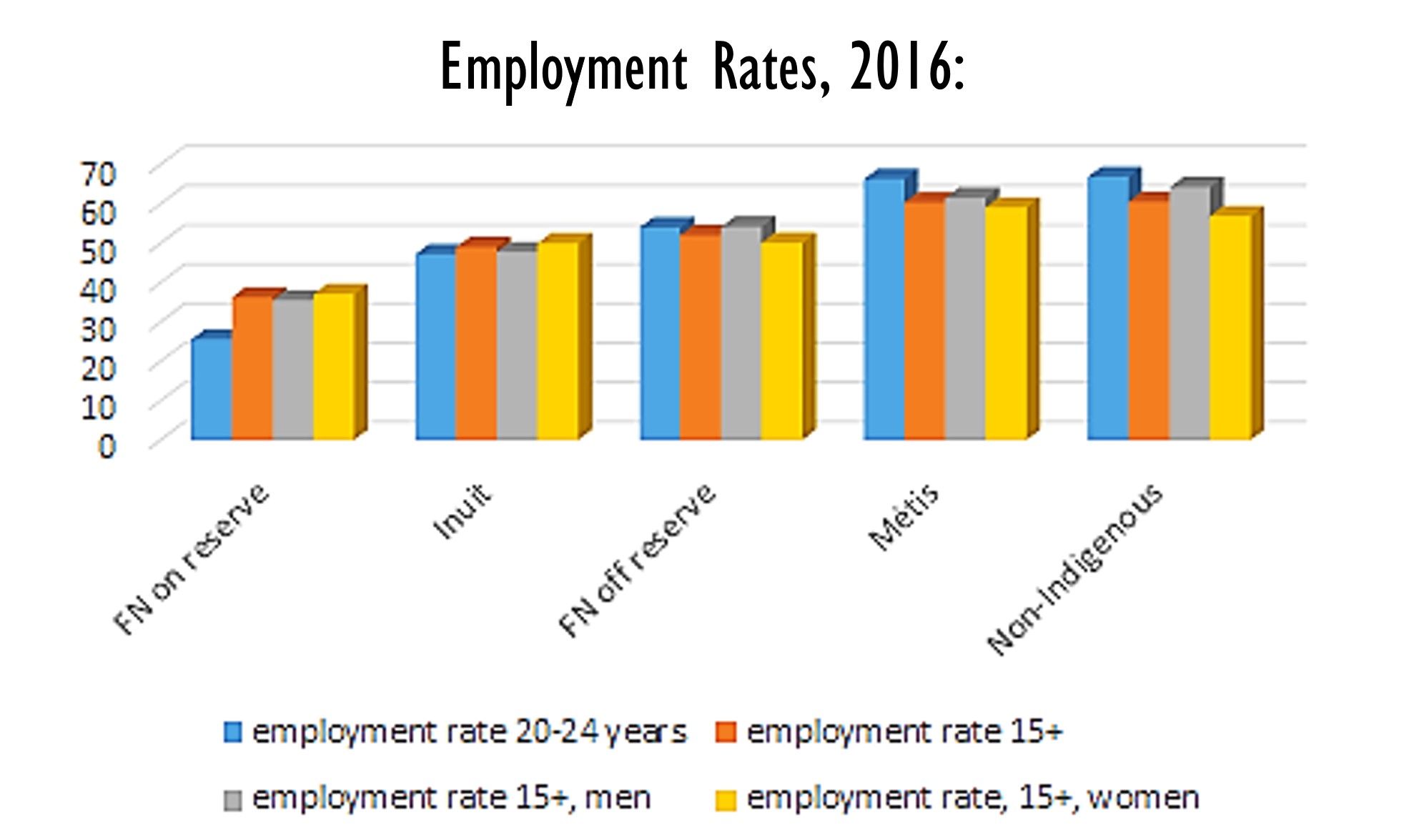

There is room to increase the Indigenous labour force participation rate, which is the fraction of the working age population that is either working or looking for work. The employment rate, which is the fraction of the working age population that is employed, is also lower for Indigenous than for non-Indigenous people, especially on reserve.

In 2016, Fiscal Realities Economists estimated that, if Indigenous people were employed at the same rate as non-Indigenous people, and if they earned the same amounts, Canada’s GDP would be 1.5% higher. 135,000 Indigenous people would no longer unemployed.[1].

Empowering Indigenous people will also add to the jobs created by Indigenous people.

The numbers in the graph below likely exaggerate the differences between groups, because they have not been adjusted for age. The Indigenous group likely skews younger within many age categories.

We should also keep in mind that not all work occurs in the marketplace. Traditional hunting, trapping, fishing, handiwork, childcare, and housekeeping are work but may not be counted as employment.

The gap between the non-Indigenous employment rate and the Indigenous employment rate varies by region. In the Maritimes it is low, ranging from 1.7 in Nova Scotia to 6.6 in New Brunswick. The gaps in Ontario (6.1), and Quebec (7.8), are substantially higher than those in the Maritimes but substantially smaller than those in Manitoba (13.5), Saskatchewan (19.9), and Alberta (11.6).

In the Yukon, North West Territories, and Nunavut, where the non-Indigenous employment rate is much higher than elsewhere in Canada, and where traditional economic activities are more likely to be pursued, the employment gap is much higher: 18.1 in the Yukon, 29 in NWT, and a whopping 43.7 in Nunavut.

Some reasons for an employment gap include distance from the home community to employment opportunities, roadblocks to economic development on reserves, poverty, and lack of formal education and training.

On-Reserve Employment

On reserve, most of the available jobs may be with the Band Administration, delivering services to the community. As many service jobs are traditionally held by women, this helps explain a higher employment rate, higher labour force participation rate and lower unemployment rate for women on reserve in 2016. We see in the bar chart above that in 2016, the employment rate for women was higher than the employment rate for men on reserve and in Inuit communities.

Besides service jobs administered by the Band, Band-owned businesses are another source of employment on reserve.

Because the Band is such an important source of jobs, it is critical that Band Administrations be fair and be perceived as fair in hiring.

Because many of the jobs in the Band Administration are funded by the federal government, there may be uncertainty as to when funding will arrive, how much there will be, and how long it will last. Wolf Collar (2020) writes that Employment Training Programs suffer from this funding unpredictability. They are often temporary and focused on short-term opportunities rather than careers. Much of the training programming is focused on getting people off social assistance rather than on building the career path of young people.

Wolf Collar would like to see the private sector and the government provide ongoing career training and support including daycare, transportation, counselling, mentorship, accommodation, and apprenticeship placements. These should be available to band members on reserve and off reserve.

Dear White Corporate America…

So read the full-page ad by Black marketing executive Omar Johnson in the New York Times on June 14, 2020, in response to weeks-long protest against the death of George Floyd and others at the hands of police.

Here are some of his suggestions for increasing employment rates and entrepreneurship among minorities, word-for-word, with “BIPOC” (Black, Indigenous, People of Colour) substituted for the word “Black”:

- Hire more BIPOC people: redouble your efforts to identify, recruit, attract, develop and elevate BIPOC talent.

- Fund educational institutions that champion BIPOC students and their futures.

- On the other side of the equation, that means helping BIPOC talent climb the ladder, and turning over power and authority to rising BIPOC leaders. Retention and promotion is just as urgent as recruiting and hiring. In fact, the former accelerates the latter.

- Oh, and while you’re at it, stop with the BS office microaggressions. Check yourself before your call a BIPOC person “aggressive”, “disruptive”, or “difficult”. That goes a long way.

- Support BIPOC organizations who are fighting to revolutionize criminal justice and public safety…

- Invest in BIPOC-owned businesses and BIPOC business leaders.

- Buy BIPOC.

Affirmative Hiring

When considering a program to hire equity-seeking groups such as Indigenous people, we have to be aware of some possible problems:

- In the short run, affirmative hiring may not be an efficient choice for the employer, whether the employer is the government, a private firm, or a Band. Even in the long run, counting (somehow) the job experience and the financial independence created for the employees, the program may cost more money than it saves.

- The selection of particular people to employ may aggravate inequality within the community e.g., the reserve.

- The people making the selection are wielding a great deal of power which may be abused.

- The program may discourage individuals from pursuing education and training opportunities, and from managing the business with maximum care.

With those four caveats in mind, we consider three ways of increasing Indigenous employment: Privatization, Procurement Contracts, and Social Job Creation.

Entrepreneurship & Privatization:

About 7.5 % of Indigenous people were self-employed in 2016, about four percentage points below the non-Indigenous rate.[2] On reserve, the rate was only 3.2% while it was 3.8% for Inuit, 6.9% for First Nations off reserve, and 9.4% for Métis.

In Chapter 29 we’ll look at special challenges facing entrepreneurs in remote communities, and in Chapters 24, 27 and 28 we’ll look at challenges to businesses on reserves.

Wolf Collar (2020) suggests privatizing the delivery of services on reserve. This means that, instead of the Band Administration dealing with the federal government, doing the paperwork, collecting the funds, and delivering the services, small businesses, privately owned and staffed by band members, would do these things. The small businesses would own equipment and other assets, even housing stock.

We could extend this concept to any Indigenous community receiving government aid. Since, as we noted earlier, a large fraction of federal spending on Indigenous people is consumed by salaries and transportation, why not have Indigenous people earn those salaries and provide this transportation? Miawpukek First Nation, in Newfoundland and Labrador, would agree. As one community leader explained,

“… prior to seven years ago we were putting out between $70-120,000 a year to go to an aviation business to charter for [our outfitting] camps. So we did a feasibility study and a business plan and looked at buying a [Cessna] 185 that would provide the service for us. It was going to have a loss of $10-20,000 per year, but if you don’t do this we are never going to own our own aircraft. We got a pilot trained and we got him employed. Now, 100 percent of that business belongs to the band.” [3]

Some of the services that Wolf Collar believes could be privatized, and which are, indeed, already privatized in some reserve communities include school bus service, garbage disposal, road maintenance, medical transportation, security, farm equipment, restaurants, and souvenir shops.

Privatization would expand the number of business owners on reserve, giving valuable experience in entrepreneurship and self-reliance. Wolf Collar believes that privatization would also save the Band a great deal of money, relieving it of the need to buy and maintain equipment and other assets, and reducing its expenditure on insurance. It would also free Chief and Council from distractions unrelated to their broader work of visioning, legislating, advocating, and stewardship.

It is important the privatization be done in a fair and transparent manner, not privileging one individual or family over another. A limited-term contract might help spread the opportunities, but it might also reduce the commitment and drive of the business owner. Employees previously working for the Band in the business should be retained if their job performance has been satisfactory and their position is still needed.

The federal government has recognized the value to Indigenous communities of providing their own services In 2019-2020 it allocated more than $2.3 billion for “Indigenous self-determined services”. This money could be directed toward Indigenous-run service providers.

Indigenous communities seek to have more of their own members involved in economic development. The 2022 National Indigenous Economic Strategy calls on all levels of government plus Indigenous Services to work with Indigenous communities to have communities themselves manage or at least co-manage economic development efforts (calls #76-78). In the future, we can envision a much smaller Indigenous Services Canada.

Indigenous communities seek to have more of their own members involved in economic development. The 2022 National Indigenous Economic Strategy calls on all levels of government plus Indigenous Services to work with Indigenous communities to have communities themselves manage or at least co-manage economic development efforts (calls #76-78). In the future, we can envision a much smaller Indigenous Services Canada.

Procurement Contracts:

The federal and provincial governments spend billions of dollars each year on goods and contracted services; this is called “procurement”. Between 1996 and 2019, less than half a percent of federal procurement was supplied by Indigenous businesses (CCAB (2019)). On August 6, 2021, the federal government announced the specific goal of procuring five percent of its supplies from Indigenous suppliers in order to encourage Indigenous entrepreneurship, beefing up the Procurement Strategy for Indigenous Business (PSIB) that was initiated in 1996.

Probably since the beginning of the PSIB, there has been a problem with non-Indigenous people winning procurement contracts by pretending that their business is Indigenous, then going on – or not- to sub-contract to Indigenous workers. Because there may be many layers of sub-contracting until an Indigenous person is actually employed, the procurement contract can become something “like the worse pyramid scheme I’ve ever seen” in the words of MP Gord Johns.[foonote]quoted in Curry (2023)[/footnote].

In December 2023, when reporters were exploring the federal government’s extremely high spending on the ArriveCan app, they discovered that non-Indigenous firms which had been awarded $400 million over ten years to work on ArriveCan and other projects under PSIB were never audited by the federal government to see whether they were actually Indigenous-owned or whether the required 33% of work was done by Indigenous contractors (Curry, 2023).

Clearly the government needs to perform such audits.

The 2022 National Indigenous Economics Strategy (NIEDB et al., p. 98) encourages governments to also

-intentionally increase the contracts going to Indigenous businesses

-make procurement contracts easy for smaller businesses to access and complete

-provide training, loans, advice and other supports for would-be contractors

-provide greater clarity as to the scheduling of public works projects so that Indigenous firms can apply

The question of fairness and efficiency arises. Should government favour a business based on its owner’s ethnicity, rather than on its reputation, experience, and costs?

Some Indigenous businesses will have little experience, higher costs, and a need for extra support such as training. From a short-run, purely financial point of view, it is not cost-effective to hire them to complete government contracts. However, their lack of experience, higher costs and need for support are due in large part to the disadvantages and discrimination they have faced in the past and may continue to face. Hiring and supporting them to complete contracts is an investment towards their future productivity as well as an act of reparation and reconciliation. A case can be made for affirmative action at least until the percentage of contracts going to Indigenous businesses approximates the proportion of Indigenous people in the Canadian population, about 5%, the PSIB goal.

The 2022 National Indigenous Economic Strategy for Canada (NIEDB et al., #101) a.so calls for publicly traded companies to be required to report on their Indigenous employment and contracting.

Social Job Creation:

Some Indigenous communities spend money creating jobs for their members. A special case is Miawpukek First Nation, the community which bought its own airplane as described above. Having become a federally recognized First Nation relatively recently, Miawpukek was able to negotiate the right to spend social assistance money on wages for members instead of welfare payments. Miawpukek also spends other money creating jobs for members, as when it purchased the airplane.

Social job creation can be a good investment, allowing members to build skills and work experience, and to enjoy the dignity of work. On the other hand, one must weigh these benefits against the benefits possible from other uses of the money. Another issue is the disincentive of band members to get higher education or specialized training if they know jobs will be provided regardless. If enough Band members choose to depend on the Band for a job, the day may come when there are no longer enough meaningful Band-sponsored jobs for everyone wanting one.

In a case like Miawpukek’s, where the Band has the right to replace welfare payments with paid work requirements, we might be worried about that kind of power in the hands of a few people in a small community where impartiality may be difficult to achieve.

In our next Chapter we consider the importance of educational achievement, and how to encourage it.