The Modern Treaty Era

Unlike water systems and other public infrastructure, houses are things that individuals and families have a chance of building and repairing themselves. Yet so much of the housing on reserves – and in Inuit communities – is poor in quality. This is reflected in low Community Well-Being scores.

Even in urban areas, Indigenous people are more likely than non-Indigenous people to live in a dwelling that they do not own and to live in a dwelling in need of major repairs (Anderson (2019)).

In 2019, the United Nations presented a report to the General Assembly establishing that over 25% of First Nations people on reserves in Canada are living in deplorable conditions, including over-crowding (25% of people) and lack of indoor plumbing (10,000 homes).[1]

One of the biggest myths surrounding First Nations housing is that all members get free housing given to them by the Band, but that is not the case. The 2016 Census records only 56,230 units of band-owned housing across all 600+ First Nations bands.[2]. Most if not all those units will be rented out, though rent is typically difficult to collect.

According to the Standing Senate Committee on Aboriginal Peoples, the overall number of on-reserve housing units needed ranges between 35,000 and 85,000.[3] However, the British Columbia Assembly of First Nations specifies a 175,000 unit on-reserve housing shortage across Canada as of 2017.[4]

Estimates will vary depending on subjective necessity, types of dwelling, communities included, and other factors. We will assume that there are approximately 70,000 new units that need to be built in order to solve the on-reserve housing crisis. This is similar to the 2011 National Household Survey estimate of 71,010 homes “not suitable” and needing “major repairs” – 62,092 on reserve and 8,920 in Inuit Nunangat. It also implies that there is at least 1 new unit needed for every 5 people who had Status and were living on reserve, or who were Inuit.

Wolf Collar (2020) reported that as of July 2019, approximately 400 Siksika families at his home reserve were waiting for housing. This out of a population of approximately 4,000 individuals on reserve.[5]

The lack of sufficient, quality housing has many negative repercussions. First is the health risk associated with poor ventilation, lack of heat, drafts, rodents, mold, and crowding. This is particularly apparent during a pandemic such as COVID-19.

Crowding, and any lack of electricity or internet connectivity, make it difficult for students to do their homework. Crowding and discomfort make it difficult for people to rest and be ready for work. Crowding also increases opportunities for sexual exploitation and bullying. It can cause tempers to flare. Wolf Collar (2020, p. 110) suggests it contributes to the large number of missing and murdered Indigenous women.

Reasons for the Housing Crisis

Reasons for the poor quality of housing on reserve may be grouped under four headings: Climate and Remoteness, Poverty, Property Rights Issues, and Administrative Problems. These all reinforce one another. Some of these may apply to Inuit and Métis communities as well.

- Climate and Remoteness

We learned in our chapter on Infrastructure that the remoteness of many reserves makes construction and delivery of supplies and labour much more expensive. The Assembly of First Nations (2013) has estimated that the cost of building a house in a remote location is 30% higher in Ontario and 50% higher in Manitoba.

The author has found that the 2016 Community Well-Being Index’s housing component score was negatively correlated with a community’s remoteness, with the correlation coefficient equal to -0.44.

Many reserves are located on inferior lands prone to flooding. In the north, extremely cold temperatures and accumulated snow and ice place stress on buildings and plumbing. Consequently, housing will deteriorate more rapidly. One third of new houses built on reserve are just replacing houses which are no longer usable.[6]

There seems to be an opportunity here for colleges and universities, even for private housing construction firms, to partner with First Nations and Inuit to design housing that is culturally and climatically appropriate, suited to the local terrain, and available in different configurations to house all the different kinds of families in a community.

- Poverty

When people are poor, they neither have savings nor can qualify for loans. How then will they buy or repair a home?

When communities are poor, infrastructure is poor, making it more difficult to construct or repair a house. Poor infrastructure also means that there will be more deterioration of the building from, for example, water sloshing out of pails, fires from candles etc.[7]

Many reserves have high rates of property neglect, vandalism and arson due to social problems related to poverty and intergenerational trauma, and to an absence of bylaws and enforcement (to be discussed in Chapter 28). There is also the issue of renters having less financial incentive than owners to maintain a property.

When Bands are poor, the Band Council lacks funds to build social housing or to assist members to finance their own housing. Bands generally have trouble making members pay rent on Band-owned properties, especially when tenants know that the Band has paid off the mortgage. Wolf Collar (2020) explains that taking band members to court over non-payment of rent is financially and politically costly. The Chief and Council are worried about losing votes, and the members of the Housing Board or Housing Department may be friends or relatives of the people threatened with eviction. This speaks to a needed separation of responsibilities, and to a need for stronger, clearer bylaws.

Wolf Collar (2020) has pointed out that some reserves lack land on which to build the needed housing. The Assembly of First Nations (2013) has asked the federal government for increased, annual, standardized funding for housing.

Property Rights

Property rights and ownership issues relate to construction and maintenance of housing on reserves. As we explore in our chapter on Property Rights, not all band members with property on a reserve have a legal document guaranteeing their right to use and improve their property. Without such a ‘Certificate of Possession’, they may be unsure whether they can live on their property indefinitely or sell the property and recoup the money they put into it: the result may be less motivation to repair and renovate. According to Sylvia Olsen of the University of Victoria, an advocate for on-reserve housing, sometimes people living on reserve have no clear understanding to whom their housing unit actually belongs – the federal or provincial government, the Band, or themselves.[8]

Second, even people with a Certificate of Possession cannot simply use their property as collateral for a housing loan with a commercial bank. Normally a bank would seize your land and house if you default on your mortgage payments. But banks are not allowed to seize reserve land.

Bands have developed some creative ways to help members on reserve get mortgages, as we will learn in Chapter 24.

In 1968, the Mohawk Council of Kahnawake instituted a revolving loan fund for home construction. The Band lends the Band member the money to build the house. The member wanting to build the house must contribute some money to the project and must show, every year, that they have life insurance, fire insurance, and other relevant insurance coverage. Once the member has repaid the loan from the Band, the member gets a Certificate of Possession to the land on which the house is located[9].

The Assembly of First Nations (2013) has asked the federal government for this kind of revolving loan funding, and also for improved access to private sector funding, social development bonds, and more First Nations-owned lending institutions. These options will be discussed in our finance chapter, Chapter 27.

The Métis Nation of Ontario, through its Home Buyers Contribution Program, offers an additional mortgage (housing loan) of up to 15% of the value of a first home to members who have one mortgage already.

The Manitoba Métis Federation offers a grant of up to $15,000 for the purchase of a first home, plus a grant of up to $2,500 to cover transactions costs like legal fees.

- Administrative Problems

In the past, housing was selected and delivered by the federal government. The typical house was a three-bedroom bungalow with a gabled roof sloping towards the front and back, with one bathroom and a basement. There were no design features to customize the houses to local needs and preferences, or to a more severe climate, or to less reliable infrastructure. According to Wolf Collar (2020), decisions about how much and what kind of housing to pay for are still made by Indigenous Services Canada, and by Canada Housing and Mortgage Corporation, a Crown corporation which subsidizes mortgages.

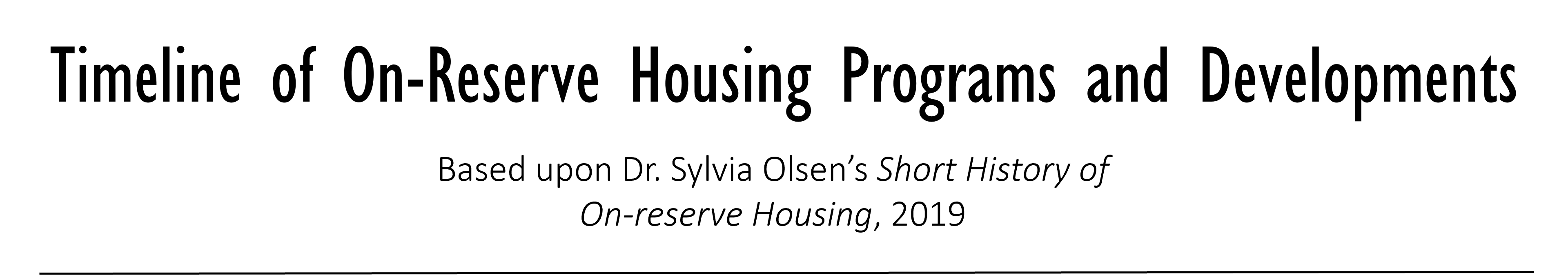

However, the federal government no longer guarantees that construction workers are qualified and that labour and materials are insured. It is no longer inspecting the work and making sure that the federal building code is being followed. There has been a “quiet devolution” of responsibility to First Nations as illustrated in the graphic below.

Since 1996 it has been the responsibility of Band governments to ensure that building materials are transported and stored carefully, that materials and work are good quality, and that houses meet federal standards. It appears that in many cases Bands have not been able or willing to do this: the quality of housing has declined since then, according to carpenter and former building inspector Alan Isfeld of Lake St. Martin First Nation.[10]

![Timeline of On-Reserve Housing Programs and Developments. Graphic by: Pauline Galoustian (Based on: A Short History of On-Reserve Housing. Content by: Sylvia Olsen; Original graphic design by: Desiree Bender; [136]](https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/sites/1088/2021/03/rf6tgyhujikoyhujik-scaled.jpg)

One of the recommendations made in Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada’s 2017 report on reserve housing was to “Strengthen… existing or new service organizations that provide technical support, capacity development or management services to interested First Nations.”[11] This could include education and training of First Nations members in building codes, guideline compliance, and general housing management.

A regional First Nation housing authority could centralize expertise, borrowing, contracting, building code compliance, bylaw creation, and bylaw enforcement while being informed by the priorities and concerns of client First Nations. Presently, the First Nations Housing & Infrastructure Council is working on just such an authority for British Columbia.[12]. Meanwhile, the Atlantic First Nations Housing and Infrastructure Network (AFNHIN) serves as a think tank, advisory group, and advocate for Atlantic Indigenous communities.

For programs to help Indigenous home buyers, see our chapter on finance.

Federal Funding for Housing on Reserve

Since 1996, most reserves not having self-government agreements have participated in INAC’s On-Reserve Housing Policy, intended to assist First Nations to finance and develop their own housing programs. In this program, First Nations receive an annual amount for housing. The total available rose from $138,000,000 million in 1996[13] to $359,204,116 in 2018-19.[14]

Using the 2018 Altus Group Construction Cost Guide, and subtracting 30% of the cost to represent the lower market value of land on reserve, and assuming that equal numbers of single room units, shared 4-bedroom townhouses, small one-bedroom houses, and three-bedroom townhouses are built, the author has estimated that the cost of building 400 homes ranged from 47 million dollars in Eastern Canada to 64 million dollars in the North.

It would cost 57 million dollars to build homes for the 400 families of Siksika First Nation mentioned earlier. Coincidentally, 57.8 million is the total amount received from Indigenous Services Canada by Siksika First Nation for all purposes in the 2018-2019 fiscal year.[15].

The $359 million provided each year from the On Reserve Housing Policy in 2018/19 could pay for 3,000 new homes in Eastern Canada or 2,245 new homes in the north. At that rate, it would take 23 years to build the 70,000 homes needed across Canada.

The cost of supplying 70,000 homes immediately in 2018 was at least 47 million per 400 x 70,000/400 = 8.2 billion, about what the federal government was spending on all Indigenous programming in 2012-2013[16], and about 50% of what Indigenous Services Canada and Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs together spent in 2018-19.

In British Columbia, where many First Nations chose not to adopt the On Reserve Housing Policy, Indigenous Services Canada is offering a New Approach for Housing Support (since 2014) in addition to the provincial government’s BC Housing Subsidy Program. The New Approach is supposed to give smaller communities the flexibility to implement a wider range of programs in support of long-term housing, including governance and capacity, one-year projects, and multi-year projects.[17] Bands must apply to get specific projects funded. Other monies are available from Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC), a Crown corporation belonging to the federal government. CMHC subsidizes repairs needed to make houses safe, healthy and accessible, and it subsidizes Bands to buy, build, or renovate non-profit housing.

Besides money for housing construction, there is need for ongoing assistance with repairs and maintenance, combined with reforms to overcome systemic poverty, scarcity of loans, property rights, lack of bylaws, and other issues previously described.

Clearly, housing is both a vital and a very expensive issue. This calls for all Canadians to collaborate and to think outside the box. One intriguing idea is featured below.

Repurposed Shipping Container Housing:

There are currently 14 million discarded metal shipping containers in the world, and that number is growing annually. Many businesses are specializing in repurposing them for housing. Aside from the environmental benefit of using a recycled building material instead of virgin materials, shipping container housing offers other advantages.

First, abandoned containers are inexpensive. A 2,000 sq. ft. home (which is equivalent to a 3-bedroom family townhouse) could be built out of six 40 ft. long containers, or twelve 20 ft. long containers for a price between $21,000 and $65,000 for site preparation, container modification, and construction (in southern Canada, presumably).[18]This does not include the price of land.

Containers are easily movable and stackable. In 2019, SwissCan Co-Development was building a 100-unit container housing project for Six Nations Reserve near Brantford. (Ross 2019).

Home construction can take between 4 weeks to 2 months, significantly less time than regular construction in which you might have crews on the site for as long as 18 months.[19] Finally, container homes are strong. Their tough exteriors do not require much maintenance and can last without deterioration for over 25 years.

One disadvantage of using shipping containers is that they must be heavily insulated to prevent rapid heat loss in winter and rapid heat gain in summer. However, it is still cheaper to install heating and cooling systems in a container home than in a regular home.[20]

- United Nations General Assembly (2019) ↵

- 2016 Census, Statistics Canada (2017) ↵

- Standing Senate Committee on Aboriginal Peoples (2015) ↵

- Merkel (2017) ↵

- Canadian Encyclopedia, “Siksika (Blackfoot)”, 2018 population estimate ↵

- Assembly of First Nations (2013) ↵

- Assembly of First Nations (2013) ↵

- Read, (2019) ↵

- from personal conversation with Allison Deer, MBA, member of Kahnawake ↵

- Ibid, (2019) ↵

- Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada, (2017) ↵

- FNHIC, (2018) ↵

- Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada, (2017) ↵

- Government of Canada, (2020a) ↵

- The financial statements of many First Nations are available by searching “First Nations Profiles” on Indigenous Canada’s website, selecting the First Nation in question, and clicking on “FNFTA” ↵

- https://o.canada.com/news/national/aboriginal-canadians-by-the-numbers ↵

- Government of Canada, (2019) ↵

- Target Box (2020) ↵

- Moore (2019) ↵

- Target Box (2020) ↵