The Modern Treaty Era

In Chapter 17 we argued that federal funding to Indigenous peoples has been inadequate, and that problems exist with transparency and accountability on the part of the federal government. As well, much of the money is used to pay non-Indigenous service providers, diluting its impact and providing opportunities for corruption.

Now it is time to acknowledge that problems with transparency, accountability, and corruption can occur within Indigenous communities as well. There are also honest problems translating the funds into successful programs and quality infrastructure.

In this Chapter we’ll examine governance on reserves; in later chapters we will examine the challenges involved in improving infrastructure, housing, employment, and educational achievement. Finally, we’ll look at business opportunities for Indigenous governments and Indigenous leaders, to help them achieve financial independence.

Colonial Legacy:

Before we discuss how First Nations govern themselves, we should acknowledge that most reserves, even those with self-government agreements, are still accountable to the federal and provincial or territorial governments in many respects. All the while, the federal and provincial ministers responsible for Indigenous Affairs have not been Indigenous and are not elected by the Indigenous communities they oversee.

Provincial and territorial governments collect excise taxes on fuel and tobacco, enforce traffic laws, and at least partly regulate education, health, gambling, family and child protection services, as well as hunting, fishing, and trapping.[1]

Federal governments maintain the Status Indian Registry and, for reserves not having a self-government agreement, enforce the provisions of the Indian Act, overseeing all bylaw creation, most land use decisions (unless the First Nation has adopted its own land code under the FNLMA), and the spending of own-source revenue. We mentioned in our chapter on the Indian Act that the money First Nations make from their resources and lands is deposited in the “Indian Moneys Trust” managed by the federal government. A First Nation must ask Ottawa for permission before spending this money: a Band Council Resolution must be passed, and the planned spending must be explained. Former Siksika Head Chief Wolf Collar writes (2020, p. 12):

“I’ve seen this process take anywhere from three to eighteen months. In some cases, bands borrow money from banks and pay interest on the loan to begin projects while waiting for their own funds to be released to them by the government.”

The 2022 National Indigenous Economic Strategy (NIEDB et al, call #85) calls on all levels of government to transfer management of Indigenous communities’ money back to the communities, and to provide financial management resources if needed.

We have seen, and we will see, that more than a century of federal government management of Indigenous communities resulted in widespread poverty on reserves and in the north, more poverty than are found in urban Indigenous or in Métis communities. Over the years, many advocates, researchers, and government commissions, such as the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples (1991-1996), have concluded that Indigenous communities must govern themselves, even if that means making mistakes at times.

Jody Wilson-Raybould (2022, pp. 228-9), a former federal Minister of Justice and Attorney General of Canada, believes that Indigenous economic development requires moving forward along two “tracks”:

“Track 1 is closing the gap on socio-economic issues – such as ensuring clean drinking water and access to quality education, and addressing issues of children and family and the unacceptable rate of kids in [foster] care.

Track 2 is the foundation and transformational piece of rights recognition. This track involves making changes to laws, policies, and practices, and doing the work of nation and government rebuilding – by replacing denial of rights with recognition as the very base of our relations. Central to this is supporting Indigenous nations in rebuilding their governing systems and implementing their right of self-government…so that they can lead and hold the responsibility and authority to fix the challenges of Track 1.”

No one cares more about Indigenous well-being than Indigenous people themselves.

First Nations Government: Elected and Hereditary Chiefs

Every First Nation, whatever treaty they have, must hold democratic elections which include all members of the Band wherever they may live [2] The default procedure, under the Indian Act , requires Bands to hold elections every two years. However, Bands may extend that to four years after meeting election procedure criteria set forth in the First Nations Election Act (2015), or they may develop their own custom election code. About 47% of 588 First Nations among the Canadian provinces have a custom system, and about 3% are entirely self-governing.

56% of bands also have traditional governance methods [3].

In early 2020, a difference of opinion between the elected Chief and hereditary Chiefs of the Wet’suwet’en Nation in British Columbia led to the hereditary chiefs blocking Coastal Gaslink employees from traditional Wet’suwet’en Nation lands. This led to protests organized there and across Canada in support of the hereditary Chiefs. For many Indigenous and non-Indigenous Canadians, it was not clear whether it was appropriate to support the democratically elected Chief, representing the willingness of community members to host a pipeline, or the hereditary Chiefs.

The Minister of Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs chose to deal very seriously with the hereditary Chiefs, working out a deal which by September 2020 had not yet been revealed to the public. One reason for this deal is that the dispute involves not reserve lands but traditional lands to which the Wet’suwet’en are claiming Aboriginal Title. Even though their claim to title has not been decided, in the meantime the government is legally obligated to ensure that the value of the lands is not diminished.[4] With respect to Aboriginal Title, it is the hereditary Chiefs that would likely hold the jurisdiction over traditional lands once Aboriginal title restores the rights Indigenous people had before European contact.

The various election systems and governance arrangements of the First Nations of Canada are a worthy subject of study in their own right, but we cannot explore them here.

First Nations Government: The Portfolio System

Leroy Paul Wolf Collar, in his 2020 book First Nations Self-Government: 17 roadblocks to self-determination and one Chief’s thoughts on solutions, details the “portfolio system” used by leadership on most reserves.

The elected Chief assigns each Councillor a portfolio such as Housing, Finance, or Elders Services. Each portfolio has its own Board, Committee, or Tribunal working on the issue. Something like Housing, which is largely funded by the federal government, would have a Housing Board which is incorporated to reduce liability and to provide a framework for the documentation which the federal government requires. Something like Elder Services might be organized by unincorporated committees.

Tribunals deliver rulings on controversial issues such as election results or consequences for band members who cause trouble in the community. The Board, Committee and Tribunal members are usually unelected people hired to the position, or volunteers.

According to Wolf Collar, problems arise when Councillors become involved in the day-to-day operations and decision making of their respective Boards, Committees, or Tribunals. This leaves little time for the Councillors to discuss and decide overall strategy and new regulations for the Band. It means that most of their time is spent applying for, managing, and reporting on federal government programs.

It also exposes Councillors to perceived conflict of interest and the anger of community members as they make micro decisions, such as the allocation of a new house, decisions which affect individual Band members whom they know personally (because the community is small).

Having the Councillors caught up micro-managing the various Boards and Committees preserves the colonial legacy: the Band Council is occupied with the task of ensuring that federal government money is spent the way the federal government wants. According to Wolf Collar, most reserves still have a Band Manager or Chief Administrative Officer who is responsible for all services, a kind of successor to the Indian Agent of old. This person should be reporting to Chief and Council, not the other way around. If Councillors were able to focus on the big picture, self-government would be more fully actualized and capacity for change would increase.

Wolf Collar recommends that Councils concentrate on Aboriginal and Treaty rights, bylaws, public safety, economic development, and cultural revitalization, rather than on service delivery.

What is Good Governance?

Governance is not the same as government. Governance is the framework and context in which government operates. Ideally it limits the ability of bad leaders and bad government to harm the community. Good governance keeps a government honest and effective.

John Graham, a senior associate with the Institute on Governance, describes governance as “the framework of structures, processes and rules that determines how families, organizations, governments and global entities make critical decisions. Governance determines who the decision makers are, whom they engage and how they are held to account”.[5]

In an article written for Inroads in 2012, and in a presentation at Queen’s University in 2018, Graham discussed several key aspects of good governance. Most can be more easily accomplished in larger communities than smaller ones. In larger communities there are more independent organizations to support and challenge the government, more sources of insight and expertise, and more anonymity.

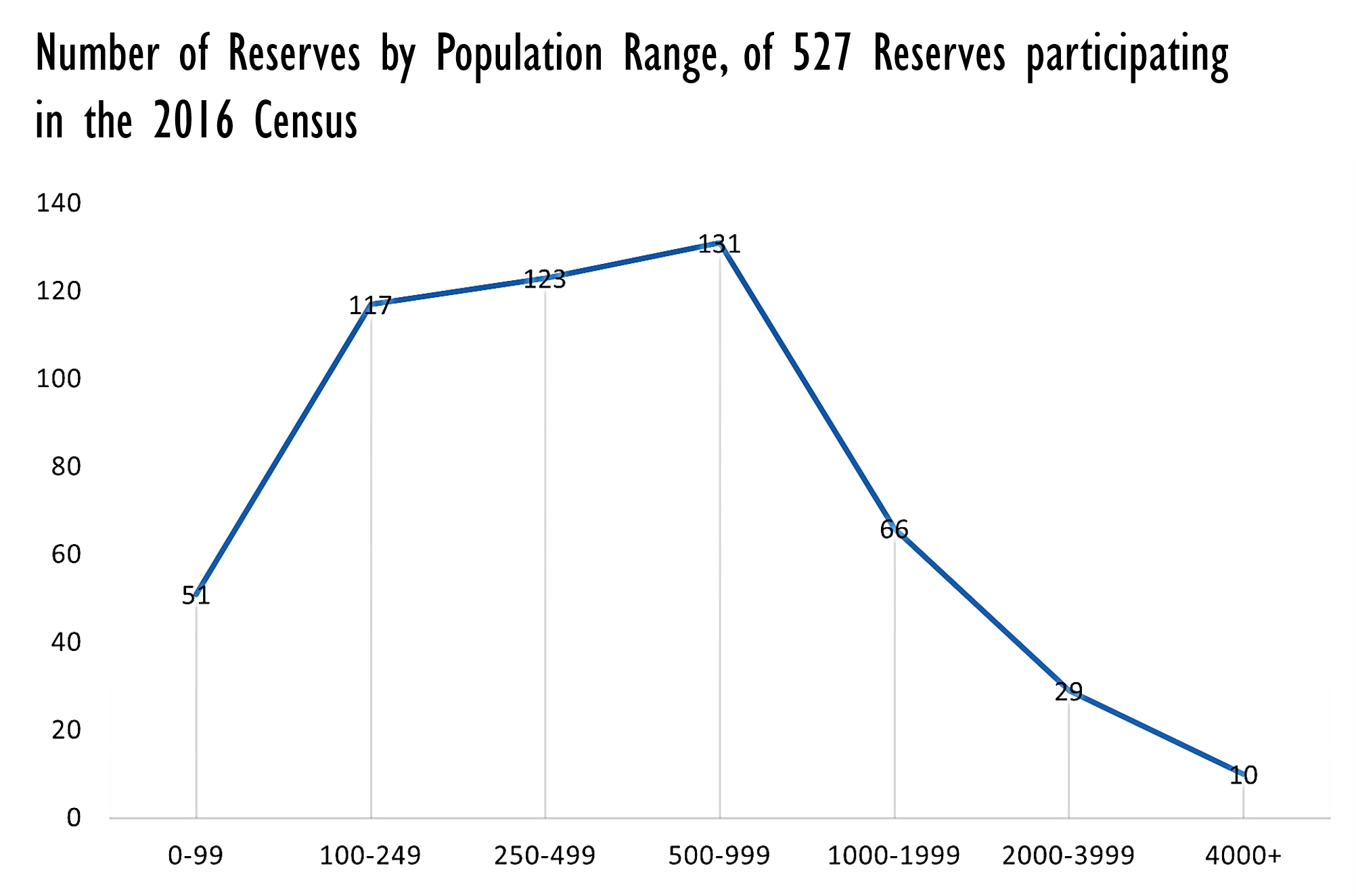

That is one reason why our larger governments (federal versus municipal) have the larger responsibilities (national defense, trade policy, food safety). But many Indigenous communities are small. As shown in the Figure below, out of 527 reserves participating in the 2016 Census, slightly more than half had fewer than five hundred residents. Ninety-two percent had fewer than two thousand residents.

Similarly, most of the communities in Inuit Nunangat are small; its largest municipality, Iqaluit, was home to 7,740 people in 2016. The largest of the 8 official Métis settlements in Alberta, Kikino, had 978 residents in 2021. The smallest, East Prairie, had 310.[6].

Graham writes[7]:

“In the rest of Canada and elsewhere in the Western world, local governments serving 600 or so people have responsibilities limited to recreation, sidewalks and streets, and perhaps water and sewers. No countries assign to such communities the responsibilities in the “big three” areas of education, health, and social assistance, let alone in other complex areas such as policing, natural resource management, economic development, environmental management and so on.”

Principles of Governance:

Governance principles include:

-

- Competent leaders

- Checks and balances

- Science-based policy and regulations

- Separation of Church and State

- Reasonably long election cycles

- Taxation of voters

- A shared vision

Competent Leaders:

While Indigenous communities on reserves, settlements or self-governing territories may be small in terms of population, their leaders are responsible for delivering a wide array of important services, including water, housing, education, child welfare, and health care. Chiefs and Councils are responsible for evaluating program delivery, researching new projects, evaluating proposals, completing applications for funding, accounting, negotiating with federal and provincial governments, and organizing elections.

Wolf Collar, who went back to school at age 50, recommends that Chiefs and Councillors should have at least a college diploma or leadership certificate, and that a Chief should have served at last one term as Councillor. (2020, p. 73)

Checks and Balances:

Canada’s federal and provincial governments, even municipal governments, are critiqued by a sizable private sector, a sizable voluntary sector, independent media, independent service quality regulators, independent courts, and ombudsmen.

By contrast, many Indigenous communities lack organized groups which can provide opposition, feedback, or advice to government. As previously mentioned, Band councillors may be, as members of boards, responsible for providing a service AND, as councillors, evaluating how well the service is provided. This creates a conflict-of-interest. Service provision and service evaluation should be done by different people.

Wolf Collar (2020, p. 144) suggests that each band have an Auditor General. The Auditor General would monitor the Band’s financial health, the validity of expense claims from Chief, Council, and employees of the Band, the contracts of consultants and lawyers hired by the Band, and the process of selecting those outside experts. Wolf Collar also recommends an Ombudsperson, from outside the community, to investigate members’ complaints.

An Elders Senate, appointed for a limited number of terms, could monitor the ethical conduct of the current Chief and Council and help with elections and the drafting of new regulations and protocols. In consultation with the Auditor General and the Ombudsperson, the Elders Senate could lay charges and decide on consequences for ethical violations.

The First Nations Fiscal Management Board works with First Nations – over 181 so far – to improve checks and balances in Band Administration. They offer tools and templates in Governance, Information Management, Finance, and Human Resources. First the Board works with the First Nation to develop a Financial Administration Law (FAL). Once it is satisfied that the FAL is being implemented in the community, the Board can issue the Financial Management System Certificate and other documents which allow the community to borrow from the First Nations Finance Authority.

The First Nations Tax Commission offers a framework for taxation on reserves.

First Nations and other communities can also seek accreditation from other organizations that test compliance with financial, quality control, environmental and a whole array of other “ISO” standards set by the International Organization for Standardization.

Science-based Policy and Regulations:

Officials cannot presume to know everything. Proven experts must develop regulations that govern health and safety, education, and transportation infrastructure, for example.

On reserves today, provincial regulations usually do not apply. Federal regulations would apply, but the federal government often does not have complete or modern regulations for particular sectors, since the sectors in question are usually managed by the provinces or territories. Thus, First Nations on reserves are not subject to as many or as stringent regulations as are municipalities.

Where reserves have created their own laws, they often lack the ability to prosecute offenders. This will be discussed in Chapter 28.

Separation of Church and State:

Public servants sometimes seem cold and distant, but it is part of their job that they treat all clients impartially. No favouritism can be shown to friends, relatives, or people who have similar backgrounds.

![Intersection of Church and State St. – a symbolic separation of paths. Photo credits to: Rachel Patterson (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0) [129]](https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/sites/1088/2021/03/5199997684_7e5db9bb84_o-scaled.jpg)

In Indigenous communities, however, leadership is considered more holistically. The responsibilities of Indigenous government may be interpreted as including cultural and spiritual leadership, and providing for one’s own clan. This can lead to discrimination.

It is very difficult to be impartial in small communities where everyone knows everyone. Eric Andrew-Gee described a 2019 election in Fort William First Nation this way:

“Besides their eye-catching flamboyance and sheer number, there’s something else distinctive about Fort William election signs: A few names appear on them again and again. The band is politically dominated by family dynasties, and in this election alone 10 Pelletiers are running for office, along with nine Bannons and seven Collinses. Nicknames help set the candidates apart, and underscore the intimacy of elections in a place where everyone knows everyone. The monikers of Ed (Thumper) Collins, Sheldon (Shezzy) Bannon and Rita May (Toto) Fenton vie for eyeballs on a crowded ballot containing more than 50 council hopefuls.

The most important names in this election, though, are those of Peter Collins and Bonnie Pelletier. They are running for chief in a community where that position wields enormous power. The importance of external affairs such as land-claim negotiations helps invest the band’s leader with outsize importance.”

Elections on reserves are often hotly contested, with a great deal of effort and money spent, at least in part because government jobs represent the highest paying jobs in town. Elections are often divisive because they are so hotly contested and because people know each other.

Reasonably long Election Cycles:

About 15% of bands hold elections every two years. This creates a lot of churn – too much money is spent, too many relationships are strained, and the Band government changes several times during the life of a long-term project. Wolf Collar writes (2020, p. 103),

“…the plans and priorities of the previous government are pretty much dead upon a change of government. In the same way, strategic plans that were completed by the previous Chief and Council often don’t get the support of the newly elected leaders. The newly elected Chief and Council will most likely facilitate their own strategic plan, even if one is already done and even if it identifies the same goals as the previous leaders’ plans, which can result in money and time wasted.”

Taxation of voters:

Both research and common sense suggest that voters who pay taxes to the government are more engaged in politics and more invested in how well their government works. Conversely, voters who mostly receive money from their government are, in a sense, being bribed to turn a blind eye to the government’s conduct.

Taxing voters motivates greater civic engagement and greater scrutiny of government and its policies. Taxation also gives government a tool to reduce income inequality.

Most Bands do not collect taxes. Naturally, many band members would vote down political contenders promising to impose taxes if elected. The federal government might be able to help: instead of clawing back any local tax revenues by reducing federal transfers, as will occur in the self-governing Nations of the Yukon, it could offer to increase its transfers to the community by a percentage of whatever is collected locally, as suggested by James Hazlett (2019)[8].

A shared vision:

Unity is important as much as possible – unity among voters, unity among levels of government, and unity between different governments working in the same region. Thus, peace-making and relationship-building are important.

- In First Nations, there is sometimes resentment against those members who live off-reserve, members without Status, or members married to non-Indigenous people.

- In cities, some leaders might be tempted to guard their networks, not wanting to share influence or information.

- In Indigenous communities generally, there is sometimes disagreement about whether action should be taken or whether it should be left to the federal government.

Financial Reporting for Reserves

We have just outlined several issues with governance in Indigenous communities, particularly on reserve. Given these issues, it is important that stakeholders, especially community members themselves, have access to accurate records of how money is spent on reserves.

As the Auditor General noted in 2002 and in 2011, First Nations have had to file detailed reports concerning spending for many years. However, this information was not available to the public. In 2013 the federal government passed the FNFTA, First Nations Financial Transparency Act.

This Act requires the federal government and the Bands to make publicly available the Bands’ Audited Consolidated Financial Statements and Schedule of Remuneration and Expenses.

The Audited Consolidated Financial Statements include the Balance Sheet, showing the net assets owned by the Band, and the Statement of Cash Flows, showing income and expenditure. The Schedule of Remuneration and Expenses shows the salaries of the Chief and Council.

These statements, as well as information about the Band’s governance, geography, and population statistics, have for several years been posted on the Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada website under “First Nations Profiles”.

There was concern on the part of First Nations that this would give information on assets, debts, and salaries to business rivals, and that it was a mean-spirited publicity stunt to blame them for poverty on reserves. On the other hand, many band members were happy to have a way to keep their executive accountable. Shuswap First Nation in British Columbia voted their chief of thirty years out of office after learning how much he had been paying himself and his ex-wife.

While the Conservative government threatened funding cuts to Bands who did not provide an Audited Consolidated Financial Statement or a Schedule of Remuneration and Expenses, the succeeding Liberal government dropped the sanctions. The compliance rate fell from 92% to 85% in just one year.[9]

In 2018 a member of Thundercloud First Nation, Saskatchewan had to file a lawsuit to get spending information from his Band Council.

Chief’s Salaries:

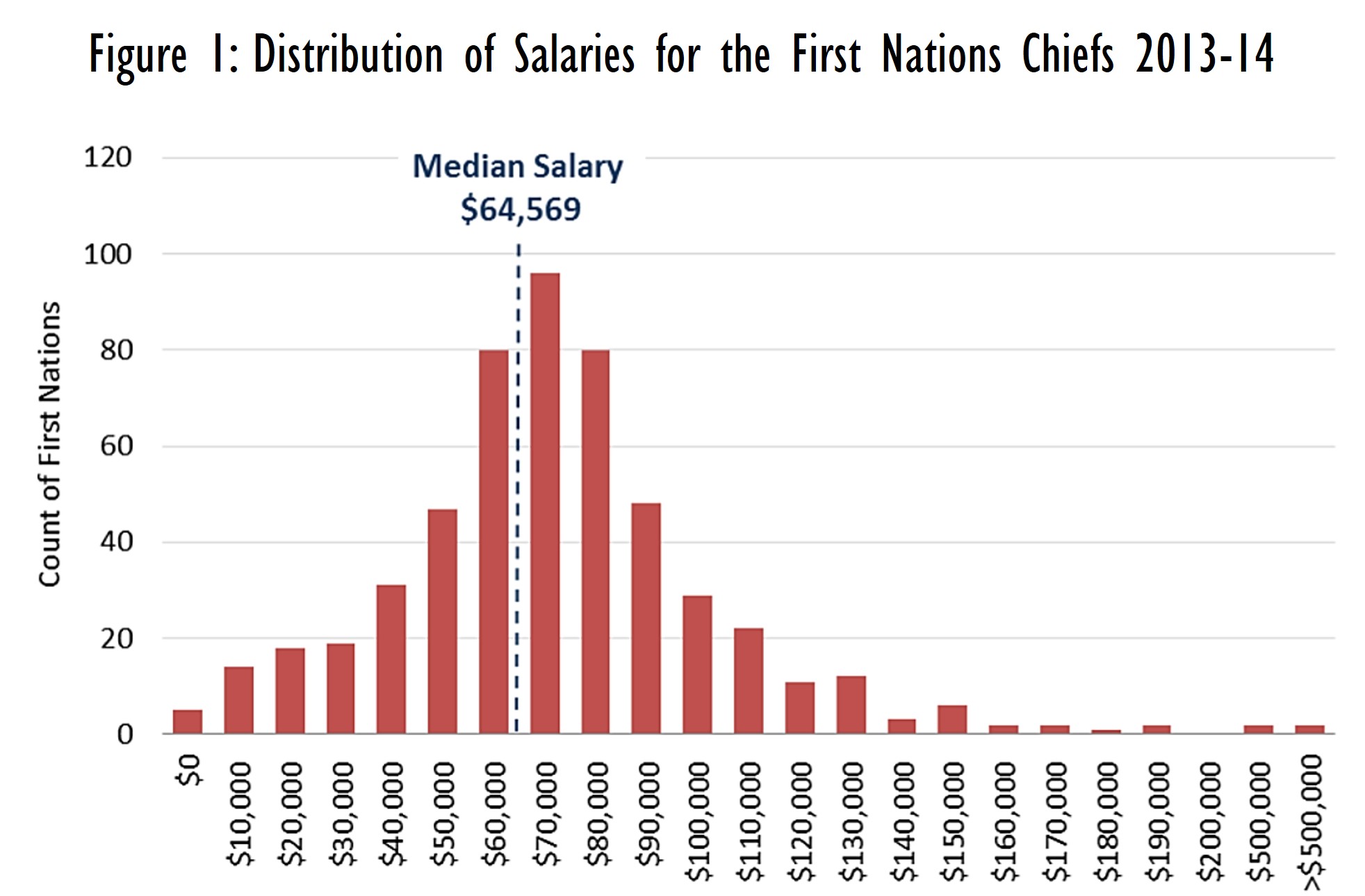

After FNFTA came into effect, there was a media storm around chief’s salaries. However, nothing much was uncovered except the case of the Kwikwetlem chief who made $914,000 tax-free by giving himself 10% of a land sale.

The graph above shows the median salary for a chief, including honoraria and excluding travel expenses, on an annual basis. No income tax needs to paid on these salaries. Only five chiefs made more than $200,000, while forty-two chiefs made less than $10,000.[10]

In two random samples of reserves and municipalities, one in Manitoba and one in Ontario, where municipalities of similar population size and remoteness were selected for each First Nation, it was more likely that the municipality did not report the remuneration of Mayor and Council than that the Band did not. The average reported chief salary, however, was substantially higher than the average reported Mayor salary, more than triple in Ontario and 80% higher in Manitoba.

Flanagan and Johnson (2015) found that Bands which have higher Band Councillor salaries have lower Community Well-Being index scores. Higher Well-Being scores are correlated with a First Nation having a self-government agreement, collecting property taxes, and being free of third-party financial management.[11]

Other helpful features have to do with property rights – the number of certificates of possession per capita and whether the First Nation has a land management agreement or earns its own revenues. We will discuss some of these features in subsequent chapters.

Difficulties inherent in current funding arrangements

As described in Chapter 17, reserves, self-governing First Nations, and Inuit territories get most of their funding from the federal government. In the case of reserves at least, this funding has been contingent on various applications and financial disclosures being sent to Ottawa. It often comes after the beginning of the year in which it is required. The amount is not known in advance.

There are several consequences. First, planning is less reliable because amounts are not assured in advance. Second, while funds for one program are delayed, funds for another program may be diverted to meet the needs of the first program, adding confusion and compromising the quality of the second program. Thirdly, delays in funding can mean delays in the program which can add to the expense of the program.

For example, as discussed in Beeby (2016), delays in a construction project, or delays between planning and construction, can mean that prices go up because of inflation; the existing infrastructure that is supposed to be replaced by the construction project continues to deteriorate; project managers on retainer continue to be paid for waiting; and the construction may end up being done in summer, a busy season when only high-cost contractors or inexperienced contractors are available.

Most of us have direct experience of the delays that can be expected when business is done with the federal government. This is even more frustrating when you are trying to provide for an entire community.

Another difficulty with the current funding arrangement is ISC’s (Indigenous Services Canada’s) hands-off approach. While this might be a refreshing change from its more controlling behaviour in the past, ISC in a way has cut Bands loose to manage as best they can with whatever funding ISC decides to dispense. If ISC assumed a greater degree of responsibility for a program’s success, it might be more inclined to improve the funding, expedite the funding, and assist the Band to make good choices about programs and projects.

Regional Governance

We have surveyed a number of challenges faced by small governments, and challenges associated with their receiving funding from the federal government. One remedy may be to have these governments share responsibilities regionally and spend federal monies regionally.

Writes Wolf Collar, “…I think we can agree, to some extent, that it may not be possible to have 600 plus individual sovereign First Nations operating as independent nation states within one nation state (Canada).”

One of Wolf Collar’s proposals is that First Nations, unlike municipalities, become a third order of government within the Constitution of Canada, having powers similar to those of the federal and provincial governments. Presumably this third order of government would not comprise 600 or more Indigenous governments.

Courchene (2018) promotes a model called CSIN (Commonwealth of Sovereign Indigenous Nations). CSIN was developed by the First Nations of Saskatchewan working with the province of Saskatchewan and the federal government, but it has not been implemented. Under CSIN, all Saskatchewan First Nations would be represented by 5 regional governments under a province-wide governance structure. For details of CSIN, see Chapter 10 of Courchene’s book Indigenous Nationals, Canadian Citizens. For more on regional governance, see the end of our chapter on Infrastructure, next.

- Wolf Collar (2020), p. 45 ↵

- Centre for First Nations Governance (2020), Appendix A ↵

- Flanagan (2019). ↵

- See the Supreme Court ruling Haida Nation v. BC, 2004 ↵

- Personal correspondence, February 2018 ↵

- Statistics Canada (Sept. 2022) ↵

- Graham, John (2012), Dysfunctional Governance: eleven barriers to progress among Canada’s First Nations. Inroads 33 Summer/Fall, pp. 31-46. ↵

- James D. Hazlett, course work, 2019, Queens Department of Economics ↵

- Akin, (2017). ↵

- reported in Smith (2015) ↵

- Third-party management is imposed by the federal government on reserves having severe financial difficulties. ↵

Bylaws are laws a community or corporation develops for itself. They are not imposed by a higher level of government.

The term "fiscal" is used to discuss the government's spending or tax revenue, the two key components of a government's budget.