The Modern Treaty Era

The First Nations Child & Family Caring Society, led by indefatigable McGill Professor and Gitksan First Nation member Cindy Blackstock, has been advocating for equitably funded Indigenous child welfare and health since 1999.

Blackstock and her team began by making legislators aware that Status children were falling through the cracks of the healthcare system. One tragic story is that of Jordan River Anderson, a little boy from Norway House Cree Nation who spent an extra two years in hospital, dying there before he was able to return home.

The delay was caused by a dispute between the federal government and the government of Manitoba about which of them should pay for his home care.

In 2007 Parliament passed Motion 296 promising to honour Jordan’s Principle. Jordan’s Principle requires governments to provide First Nations children with medical care first, then argue about which branch of government will pay the bill.

In 2020-21 the federal government would spend $5.82 million on Jordan’s Principle and the similar “Inuit Child First Initiative.” But back in 2007, it dragged its feet.

To keep costs down, Indigenous & Northern Affairs Canada (INAC) and Health Canada limited the principle to children with complex needs and multiple service providers. They also failed to publicize the principle.

So in 2007, First Nations Child and Family Caring Society filed a complaint against the federal government with the Canadian Human Rights Commission, arguing that the federal government discriminated against First Nations children and their families by failing to equitably deliver health care (per Jordan’s Principle) and family and child services to children on reserves. The Caring Society’s own federal funding was cut off 30 days later.

The federal government spent several years and over $3 million fighting the challenge, arguing that spending on reserves should not be compared to spending elsewhere, and that this spending is not a service pursuant to the Canada Human Rights Act.[1] In 2016 the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal ruled in favour of the Caring Society. It has since issued more than 6 non-compliance orders against the federal government.

We’ll now study the 2016 CHRT ruling in detail, as it provides a lot of interesting information on federal funding of child welfare on reserves.

The background to the ruling describes how, after World War II, when the social welfare system we know today was developing, provinces and territories were reluctant to extend assistance to reserves and other Indigenous communities, claiming that this was a federal responsibility. So in 1965 the federal government committed itself to providing the needed services to reserves.[2]

Over the next 25 years, concerns developed that the services being provided were minimal and not culturally appropriate. Many children were being removed from their communities for fostering or adoption. In response, the federal government developed the First Nation Child and Family Services (FNCFS) program. Fully operational in 1990, the program created community-based FNCFS agencies to manage and deliver child welfare services, with funding coming from the federal government.

The mandate was to provide children and families “with a full range of child and family services reasonably comparable to those provided off reserve by the reference province or territory”.

This wording was changed to “reasonably comparable to those available to other provincial residents in similar circumstances within Program Authorities” after the 2011 petition to the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal was made. Why do you think this change in wording was made?

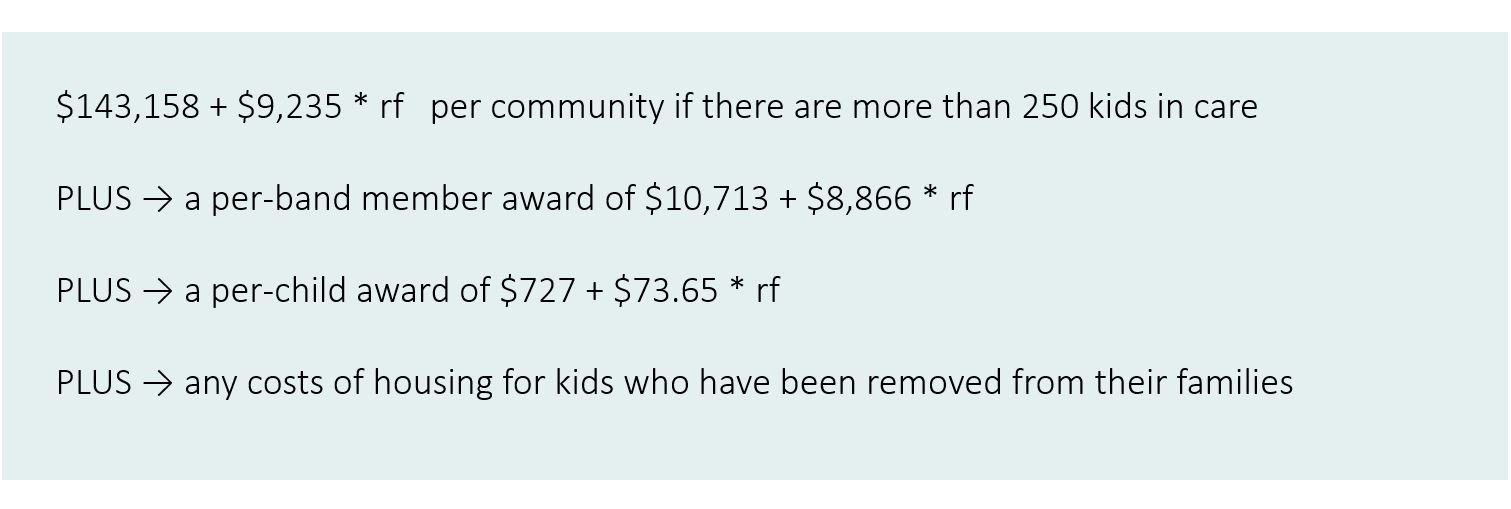

How much funding were FNCFS agencies supposed to receive each year? It appears that most of the funding was calculated according to a formula. The formula involved a “remoteness factor” (call it “rf”) between 0 and 1.9. The more remote the community, the higher the remoteness factor, to a maximum of 1.9.

This formula assumes that about 6% of a community’s children are in care; that about 20% of families require services; that there is one childcare worker and one family support worker for every twenty children in care; and that there is one supervisor and one staff person for every five childcare workers.

The actual fraction of kids in care has ranged between 0 and 28%. The formula looked like the following: A 2008 Report of the Auditor General of Canada criticized the funding formula, calling it outdated, inflexible, and designed for agencies serving one thousand or more children. The Auditor General also found fault with the program for not having standards for culturally appropriate care, for having no way to compare its services to provincial services, and for not adequately monitoring results.

A 2008 Report of the Auditor General of Canada criticized the funding formula, calling it outdated, inflexible, and designed for agencies serving one thousand or more children. The Auditor General also found fault with the program for not having standards for culturally appropriate care, for having no way to compare its services to provincial services, and for not adequately monitoring results.

The CHRT (2016) agreed that funding should not be based on a formula, but on standards of care. The amounts in the formula did not increase between 1995 and 2011, and, according to a report done by the federal government and the Assembly of First Nations, they resulted in average spending per child in care being 22% less than the average spending per child in care in provinces.[3]

Abandonment of the Formula-Based Approach:

In February 2018, the federal government, responding to a 4th reminder from the CHRT regarding the 2016 ruling, instructed FNCFS agencies to spend whatever is necessary on their mandate. Indigenous Services committed to covering all actual costs for prevention, intake, investigation, legal fees, and building repairs retroactive to January 26, 2016, the date of the CHRT ruling. Spending on this file would rise 22% between 2018-9 and 2020-21.

A year later Parliament introduced Bill C-92, An Act respecting First Nations, Inuit and Métis children, youth and families. This Bill enshrines in federal law the following goals:

- that when determining the best interests of a child, the child’s cultural and spiritual needs, the child’s own views and preferences, and the need for an ongoing relationship with the child’s family and community be considered

- that no Indigenous child will be taken away from a family for reasons of poverty or parental health problems

- that if an Indigenous child needs to be taken away from a family, that the foster family be selected with priority going to those who are most closely related, part of the community, and able to keep siblings together