The Modern Treaty Era

In this Chapter we’ll consider how much money Canada’s federal government allocates to Indigenous individuals and communities. Some of this could be considered obligatory, in keeping with treaty responsibilities or in compensation for past wrongs. Some could be considered part of the government’s aspiration to enhance all citizens’ well-being. In this day and age, we expect social spending from the government.

Some History:

At the time of Confederation, Canada had no social assistance as we know it today: no publicly-funded medical care or schools, and no public pensions. A very different mentality prevailed. The federal government at that time had no intentions regarding the Inuit, no inkling of duty towards Métis communities, and no willingness to spend a nickel more on First Nations than was promised in the various Treaties or that was necessitated by emergencies such as famine.

It might be said that the federal government’s sense of responsibility to provide a social safety net for anyone, Indigenous or non-Indigenous, awoke during the Great Depression and became quite energized as soldiers returned home after World War II.

While the provinces and territories took on the responsibility to deliver health care, education, and social assistance to Canadians not living on reserves, the federal government expanded its service delivery to Status Indians on and, to some extent, off reserves. It now funds health care, education, income support, child welfare, and infrastructure on all reserves. There is, however, no formal statement of what this support entails, and the funding that individual reserves and other Indigenous communities receive has evolved in an ad-hoc manner.

Until the Supreme Court decision Daniels vs. Canada (2016) codified Canada’s obligation towards Métis and non-Status persons, spending on these two groups has been small.

Mark Milke (2013) has investigated the amount of government spending on Indigenous persons since 1947; most of his data relates to people with Indian Status. While many government ministries and agencies have spent money on Indigenous communities, only Health Canada, Employment and Skills Development Canada (now Employment and Social Development Canada), and the department directly responsible for Indigenous programs (now called Indigenous Services Canada) explicitly identify their spending on Indigenous people:

Milke’s estimates are conservative in that some spending on Indigenous people was not recorded and could not be counted, and because administrative expenses are not included.

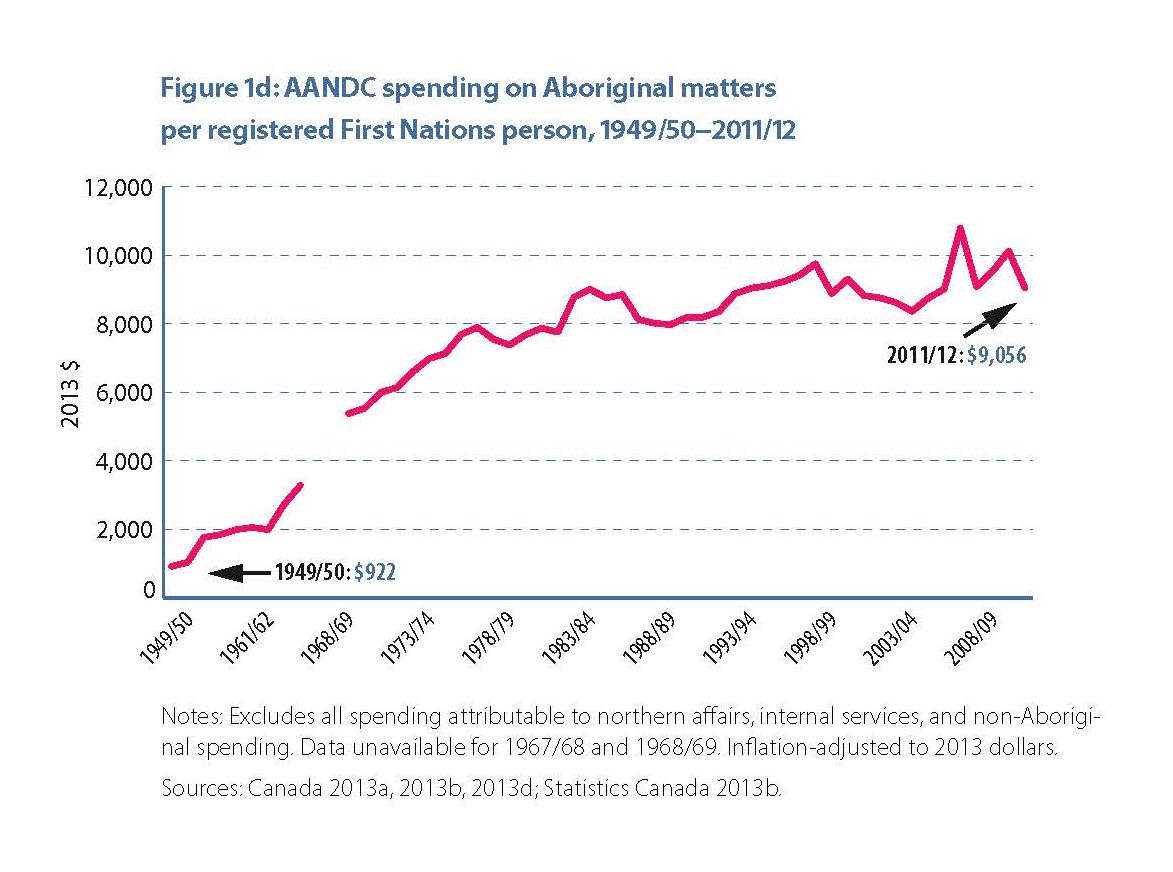

In the graphic below, AANDC stands for Aboriginal and Northern Development Canada. This is what Indigenous Services Canada used to be called. It is the federal ministry in charge of spending on Indigenous programs.

Taking his data as given, spending on Status persons has increased dramatically, from $922 per person, adjusted for inflation, in 1949/50, to $9,056 pr person in 2011/12. Meanwhile, spending on all Canadians rose from $1,504 per person to $7,316 per person. (These amounts are for specific programs and do not include things like National Defence, highways, etc. They are adjusted for inflation.)

$922 per Status person in 1949/50 is terribly low, considering that most Status people at that time lived on reserves, and that their living conditions were typically extremely poor. All the Band’s financial decisions and economic activity had to be approved by the Indian Agent appointed to that reserve. Provinces were not providing health care or education to reserves as they were to towns and cities – that kind of spending had to come from the federal government.

We see that program spending on Indigenous persons compared to all Canadians began as lower than average and by 2011/12 was higher than average.

We also see a stagnation in spending during the 1980s and 1990s. Notably, these were the years just after the Indian Agents were let go and Bands were expected to manage themselves. In 2011/2012, federal spending per Status person was no higher than it had been in the early 1980s, despite the demonstrated poverty on many reserves.

The stagnation would last until 2016.

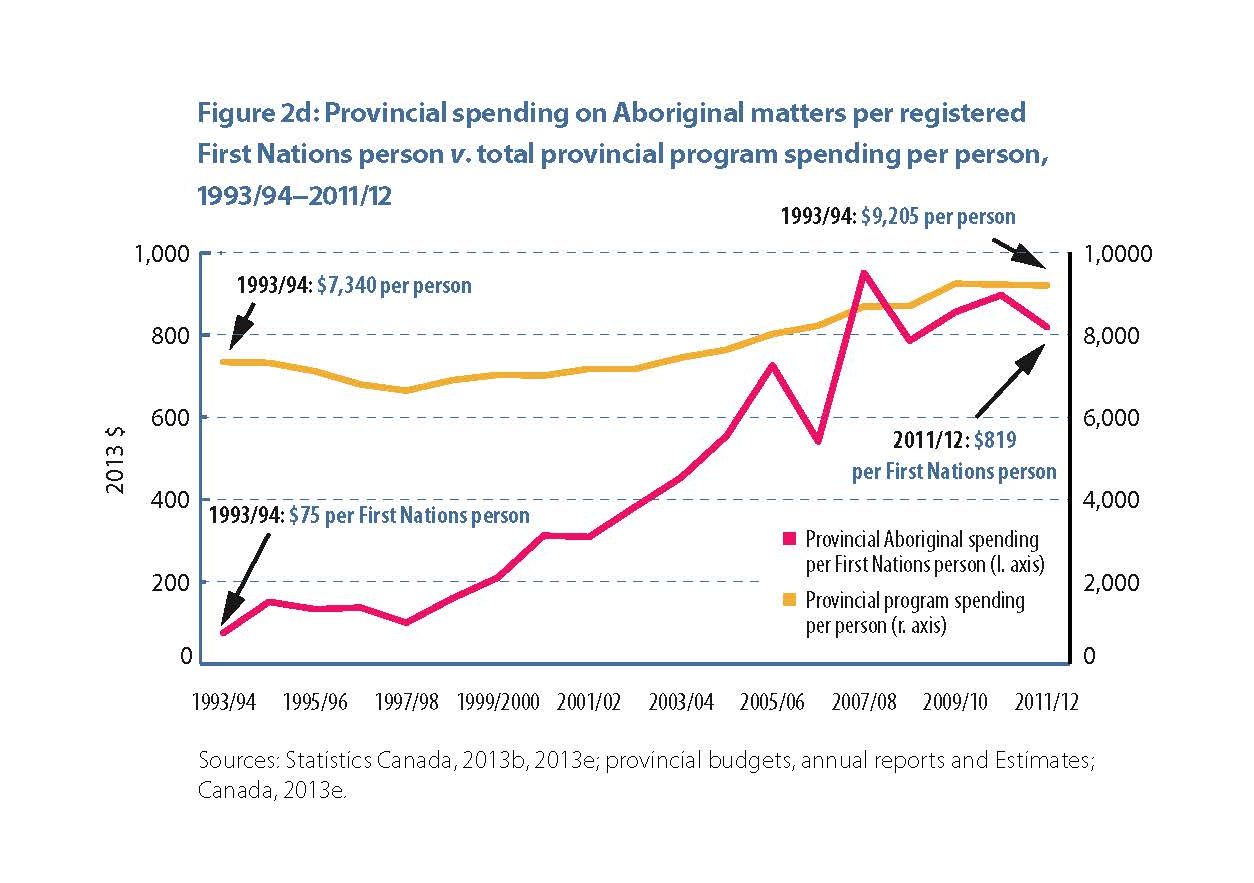

Meanwhile, provincial spending rose from $75 per Status person in 1993/94, compared to $7,340 for all citizens, to $819 per Status person compared to $9,205 for all Canadians. Each line in the graph below is calibrated to a different axis (left or right), because the provinces spend so little on Status people.

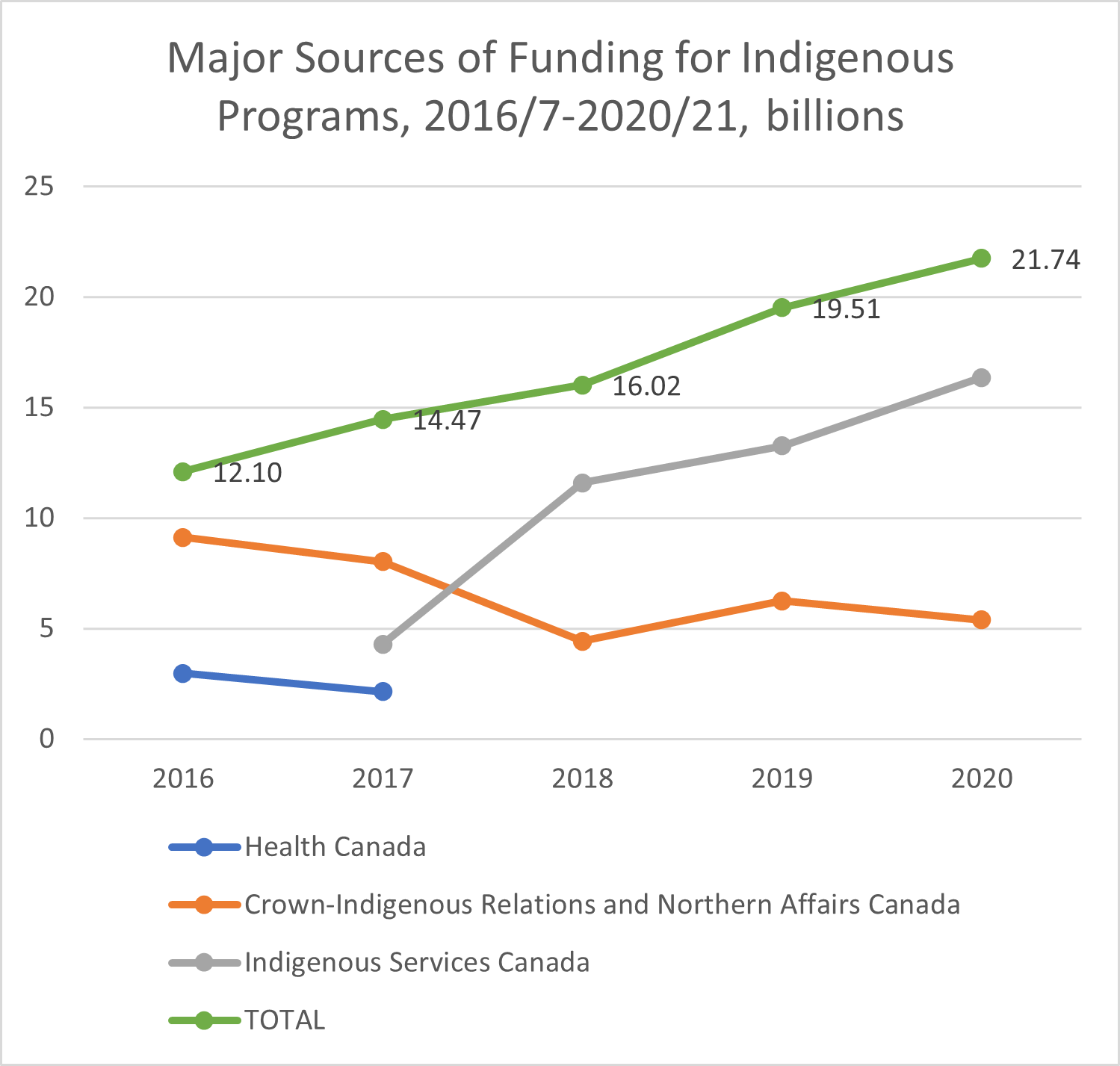

More recently, there has been a big push to increase spending on Indigenous programs since Prime Minister Justin Trudeau came to office in 2016.

The graph seems to suggest that Health Canada stopped spending on Indigenous peoples. This is not at all the case; it’s just that the amount spent by Health Canada on Indigenous people is now included as part of the Indigenous Services Canada budget.

As shown on the chart, in 2020-21 Indigenous Services Canada spent $16.35 billion in 2021, a decent amount representing 5.4% of the government’s estimated budgetary spending.[1]

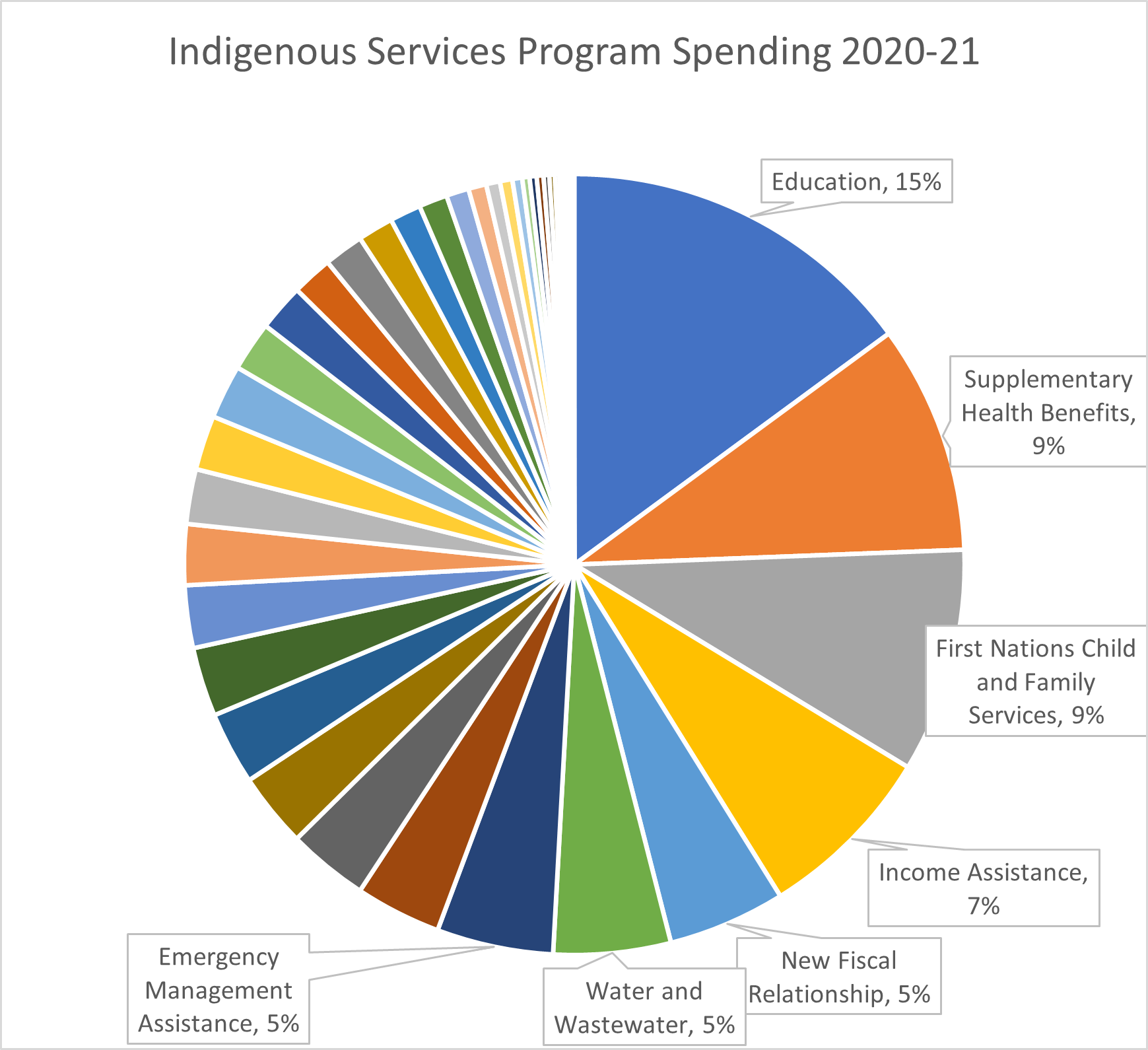

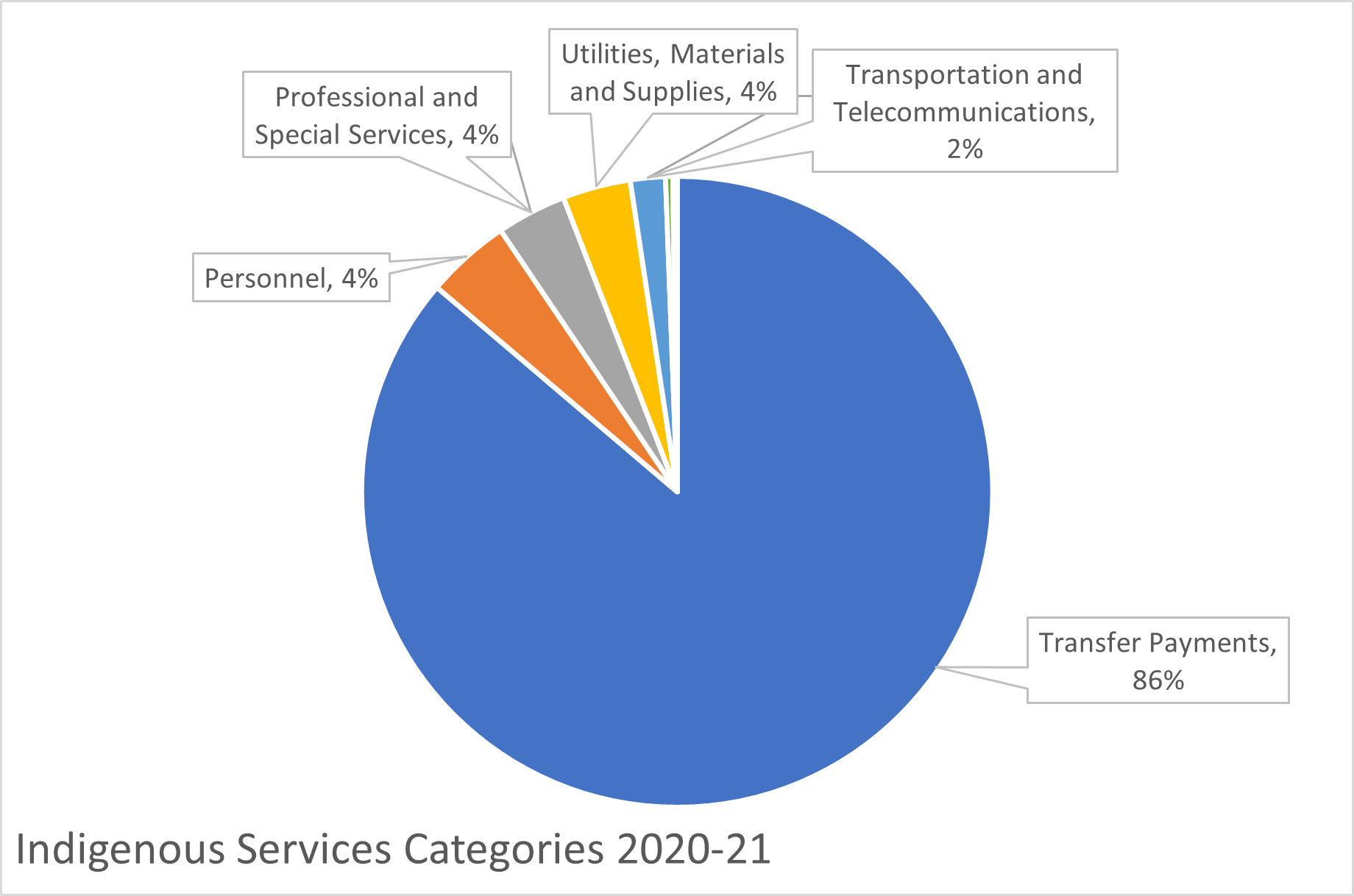

What did it spend on? The following pie chart gives us the details.

The largest category is Education.

The next largest, Supplementary Health Benefits, is paid to all Status people wherever they are living.

The large grey wedge, First Nations Child and Family Services, involves child safety, welfare, and foster care. It is 22% higher than it was two years before because of the federal government’s 2018 decision to spend whatever is needed/requested. See our next chapter for details.

“New Fiscal Relationship” refers to 10-year grants to qualifying First Nations. This gives First Nations predictable funding and eliminates the chore of applying annually for funds. “Emergency Management Assistance” was directed in large part to fighting Covid-19.

The next largest category is $5.82 million “Jordan’s Principle and the Inuit Child First Initiative,” which involves health care and will be discussed in our next chapter.

Other important categories include $4.69 million for Urban Indigenous Programs (the darkest green wedge) and $3.71 million for Housing (the lightest grey wedge). $4.69 million will not go very far among the many Indigenous people who live in cities; see Chapter 30 for details. Housing is a serious issue on most reserves; $3.71 million seems a very small response.

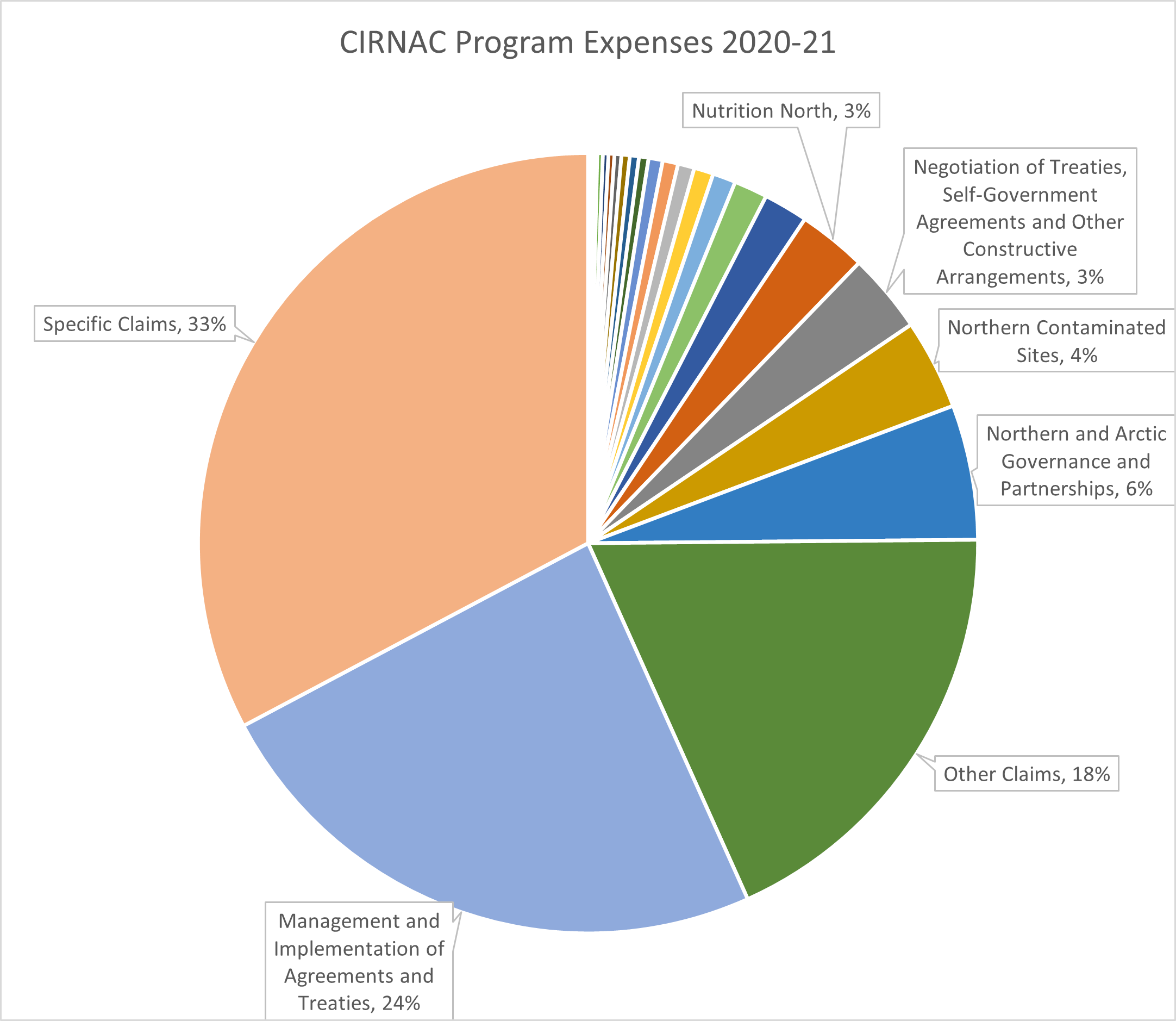

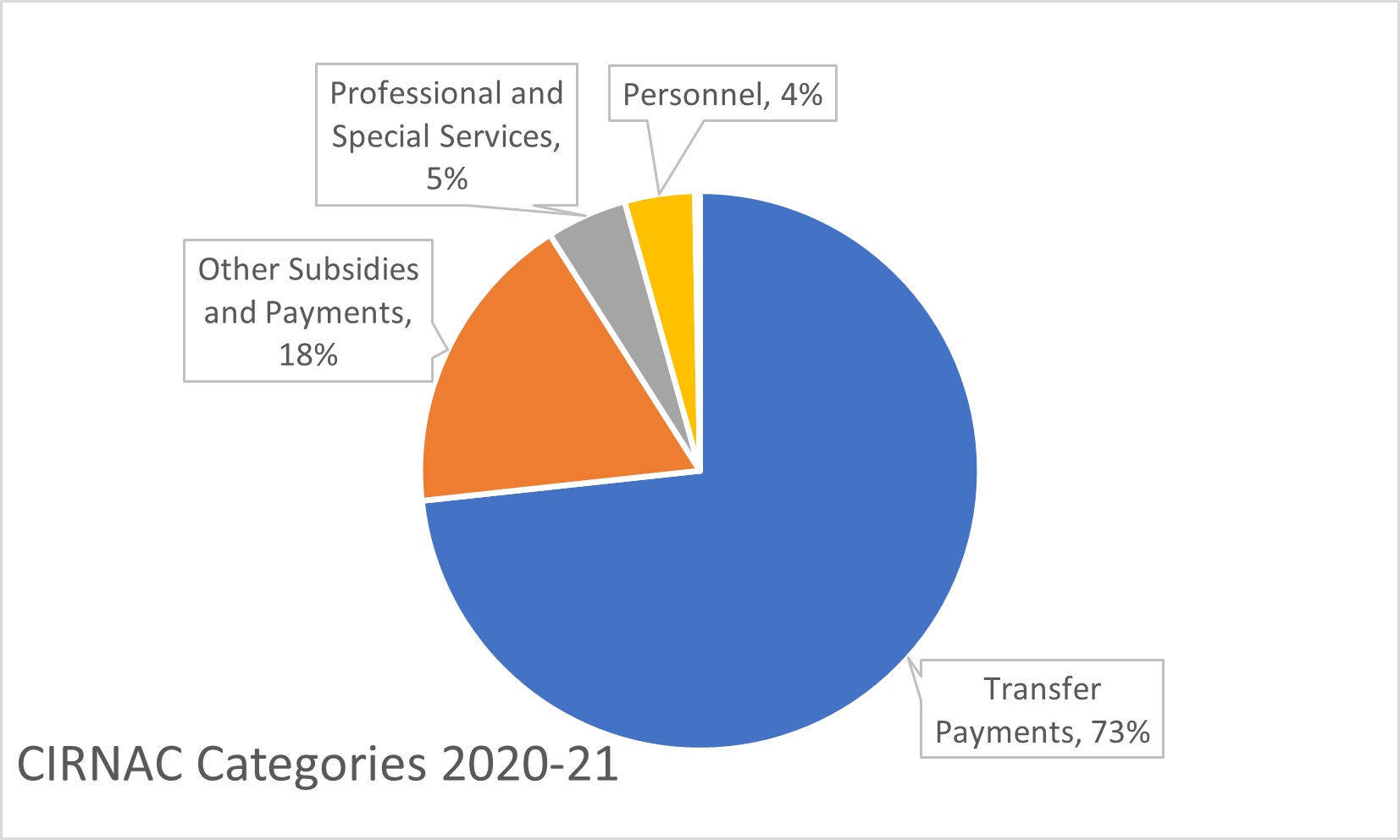

The federal government also spends on Indigenous matters through Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada, as shown in the pie chart below.

When we look at the money spent by CIRNAC (Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada), we see that much of the money goes to fixing things that weren’t done right in the past. From “Specific Claims” -arising from treaties not being implemented properly – to “Contaminated Sites”, CIRNAC’s budget shows the consequences of past exploitation of Indigenous peoples and their traditional territories.

Where does the money go?

We have just seen where the money goes, literally, but why is this amount of money not producing better outcomes? Why is the Canadian government spending billions on Indigenous programs, with so little to show for it? There are at least four reasons:

- amounts have been inadequate relative to the past mistakes that need to be corrected, and relative to current needs

- much of the money has ended up as revenue for non-Indigenous service providers

- the federal government has not been held accountable for the how the money is spent

- governance issues on reserve, and complications due to how money is given to Bands, may be preventing optimal use of the money (to be discussed in Chapters 19-21)

Let’s proceed to explore these first three points.

-

Amounts have been inadequate

Before we use data to make the case that the Canadian government hasn’t spent as much as we might like to think on Indigenous communities, consider the logic. Is a marginalized group, often living far from the public eye, for generations associated with unfavourable stereotypes and racist slurs, likely to have received appropriate support from non-Indigenous voters or the governments elected by those voters?

A quotation from Sherlock Holmes comes to mind, something the fictional character said when traveling through the English countryside[2] :

“The pressure of public opinion can do in the town what the law cannot accomplish. There is no lane so vile that the scream of a tortured child, or the thud of a drunkard’s blow, does not beget sympathy and indignation among the neighbours, and then the whole machinery of justice is ever so close that a word of complaint can set it going, and there is but a step between the crime and the dock. But look at these lonely houses, each in its own fields, filled for the most part with poor ignorant folk who know little of the law. Think of the deeds of hellish cruelty, the hidden wickedness which may go on, year in, year out, in such places, and none the wiser.”

Think indeed of the con artists, the predatory professionals, the incompetents who consider remote communities easy marks. Think of the suffering and poverty which may go on, year in, year out, in such places, and none the wiser. Which did go on in Residential Schools, and which few non-Indigenous people knew about, nor were they inquiring.

Historical spending data is not easy to find. It is complicated by the fact that for decades, the ministry that spent on Indigenous programs was combined with the ministry that spent on economic development in northern Canada. So we had Indian Affairs and Northern Development in the sixties, later Aboriginal and Northern Development Canada (AANDC), and then Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada (INAC). In 2018, this Department was broken into two separate departments, one called Indigenous Services, focused solely on Indigenous peoples, and one called Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs, which serves both Indigenous and non-Indigenous citizens.

Crown-Indigenous relations and Northern Affairs Canada (CIRNAC) is mostly responsible for general spending categories such as environment, land claim negotiations, governance, resource development, and reconciliation strategy.

The Department of Indigenous Services (ISC) has a much more service-oriented function and is the source of funding for most categories directly related to Indigenous people’s immediate material well-being.

Some of the categories of spending do overlap. Both CIRNAC and ISC spend on governance, climate, education and facilities.

We saw in the line graph of federal spending by Mark Milke that federal spending on Indigenous matters stagnated during the 1980s and 1990s. Then during 1996-2016, the federal government capped its funding of reserves, allowing funding to grow only 1% percent per year, despite the average rate of inflation being 1.9% during this period (author’s calculation), and despite population growth on reserve.

After 2016, spending has surged. During they yeras 2015-2021, the federal government allocated between 4 and 5.4 of its program expenses on Indigenous people. Since Indigenous people made up about 5% of the Canadian population at the time, this does not seem excessive.

Spending on Reserves compared to Spending on Provinces and Territories:

It is the long-standing policy of the government of Canada to distribute money to Provinces and Territories based on how much their needed spending exceeds their tax revenues. Distributing money to reserves can be thought of as much the same exercise, except that reserves are not expected to raise their own tax revenues.

All provinces receive some amount of Canada Health Transfer (for healthcare) and Canada Social Transfer (for social assistance, childcare, and post-secondary education); less prosperous provinces also receive the more general “Equalization Payment”. The purpose of Equalization Payments is to ensure the same standard of living for all Canadians.

The table below compares the total amount of money transferred by the federal government to various entities.[3]

![Consolidated Table of Federal Transfers (by Region/Province) for 2015-16 compared to 2018-19. Based on Reference Tables and Reports of the Department of Finance, 2017. Consolidated by: Anya Hageman & Pauline Galoustian [118]](https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/sites/1088/2021/03/5-8.jpg)

Consolidated Table of Federal Transfers (by Region/Province) for 2015-16 compared to 2018-19. Based on Reference Tables and Reports of the Department of Finance, 2017. Consolidated by: Anya Hageman & Pauline Galoustian [118]

We see that the amount reserves receive per person seems in line with what northern territories receive per person. The amount reserves receive per person rose almost 25% between 2015-6 and 2018-9, more than enough to cover inflation and population growth. This was in keeping with the Trudeau government’s promise to honour treaty commitments and invest in reserves.

In addition to the $22,588 per person spent on reserves by Indigenous Services Canada, Crown-Indigenous relations and Northern Affairs Canada contributed an additional $6,337 per person to fund land claim negotiations, treaty settlements, northern nutrition, and northern development.[4]

According to the Parliamentary Budget Office, of the $18,400 per person allocated to reserves in 2016:

- 2% was not actually given, but was included to make up for the fact that reserves do not pay income tax to the federal government

- 16% funded Band governments

- 16% was for social benefits

- 66% was for infrastructure and programs

Spending on off-reserve Status persons:

The federal government also spends on Status persons who do not live on reserve. According to the Parliamentary Budget Office (2017), in 2015-6 the federal government spent about $1,860 per Status person not living on reserve. $1,388 went to supplementary health care and $415 to postsecondary education.

The Parliamentary Budget Office noted that 35% of the health care spending goes to transportation costs, leaving $902 per person. Besides transportation to hospital, medication, dental care, vision care, medical supplies, and mental health counselling are covered. Status persons, and also Inuit, can receive supplementary health care at any health care facility; the federal government will then reimburse the facility. The postsecondary money goes to paying for students’ tuition, books, travel to school, and living expenses, and also to the Indspire program, which provides scholarships and educational programs.

Status persons also can benefit from administration of the estates of deceased persons ($5 per person per year) and support for entrepreneurs ($50 per person per year).

Spending on Indigenous People Generally:

In 2016 we had the federal government spending $1,800 per Status person not living on reserve multiplied by 416,000 individuals, plus $18,400 per Status person on reserve multiplied by 329,999 individuals, amounting to $36.8 billion.

Additionally, Health Canada, another federal ministry, spent serious money on primary health care, supplementary health benefits, and health infrastructure support for First Nations and Inuit. In 2016-2017 this was about $3.5 billion.[5]. Assuming Health Canada spent at least $3 billion on Indigenous peoples the year before, that brings us to $9.8 billion, bringing us close to the $11 billion the government said it was spending on Indigenous peoples.

The rest of the money was coming from other ministries such as Employment and Social Development Canada and from Crown Corporations like Canada Mortgage and Housing.

We have now put the amount spent on Indigenous programs into perspective given other program spending. Another perspective we need is our knowledge of the higher mortality rates of Indigenous people, and the lower Community Well-Being scores of the places they live.

In addition to the problem of the amount of spending having been, if not continuing to be, less than adequate, there is the second problem of money ending up in the hands of non-Indigenous service providers.

2. Money Spent on Non-Indigenous Service Providers

It has long been noted that a lot of money intended for Indigenous needs benefits non-Indigenous service providers instead. In 1975, Hugo Muller wrote:

“I am not a statistician, but if I were, I would have a very interesting time figuring out exactly what percentage of the huge Indian Affairs budget is really spent by Indians on Indians.

Let me give just one example. At a certain period of this decade, a number of Indian students from James Bay were sent out to places [like] Noranda, Quebec, in order to attend high school there….There was a time when we had over a hundred students in Noranda, let’s take 100 for easy figuring.

Foster parents boarding the students were paid $100 a month, and clothing vouchers issued three times a year amounted to $125 a season. Tuition was $820 per year per student, paid to the School Board [in Noranda]. For ten months, the cost per student was $1,945 – for one hundred students $194,500. And that does not include the transportation charges (they were flown in and out, since there are no roads in that area). That would be over two hundred thousand dollars in all.

This was money spent for Indian education from the Indian Affairs budget, and only [comprised] a small part of the total cost of educating the high school students. But all this money ultimately ended up in the cash-registers, bank accounts and pockets of the white people living in the Noranda region.

The Indians did not benefit from it – as a people. If all these students had been educated in their hometowns, and all these hundreds of thousands of dollars would have flowed into the Indian community, providing jobs and services and generating development in their own surroundings, then, and only then could we begin to say it was beneficial to them.

…And until we see a dramatic change in that emphasis, we cannot complain that we are spending too much on the Indians where most of the money flows back into the pockets of merchants in Noranda, pilots in Val D’Or, civil servants in Ottawa, teachers in Hull, officer planners in Toronto, and so on. It helps our economy. Not the Indian economy. And as long as we do this, we cannot really ask the Indian, “Why don’t you stand on your own feet?” especially when we are forever telling him to move there, go to school here, not to live there, not to move around so much, and whatever else we can find to say to him.”

Another example of misplaced spending is the tendency, on the part of many child welfare agencies, to pay foster parents to raise children, rather than spending money supporting the children’s own families with coaching, counselling, rent payments etc. This tendency has impacted thousands of Indigenous and non-Indigenous children. As we will learn in our next Chapter, First Nations have been taking Child and Family services into their own hands to remedy the situation. Change is happening in other communities too. For example, in 2019, Kingston, Ontario’s Family and Child Services announced “the biggest change in more than 125 years of service”:

“… in the past, such as with Indigenous peoples, we’ve sometimes failed to look beyond the child to how the child is connected to family, culture and community. We’ve come to believe that these connections are essential to a child’s wellbeing, too. Every child needs to know where they come from and who they’re connected to. The outcomes for the kids we serve are always better when these bonds are strengthened. That’s why we’re refocusing our work so that we see every child in the context of their connections to family, culture and community. And we will preserve and promote those connections. For that we will need to make fundamental changes to what we do and how we do it. That’s why this is such a monumental change for our Agency.”[6]

Has anyone be asking how wisely the federal government allocates its money for Indigenous people?

The following pie chart for Indigenous Services Canada (ISC) spending in 2020-21 looks pretty efficient. Eighty-six percent of money spent appears to be going directly to Indigenous people.

CIRNAC also appears efficient, with a maximum of 9% going to staff and lawyers. The payments include compensation to Residential School survivors.

Generally, however, there has been a lack of accountability for how money is spent at ISC and CIRNAC.

3. Lack of Accountability in the Federal Government

We mentioned in a previous Chapter that there is no document, not even the Indian Act, that spells out the federal government’s obligations to Indigenous people. This was a focus of criticism when the Auditor General, Canada’s spending watchdog, reviewed the federal government’s delivery of programs for First Nations on reserve in 2011. The Auditor General wrote:

While the federal government has funded the delivery of many programs and services, it has not clearly defined the type and level of services it supports. Mainly through INAC [Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada], the federal government supports many services on reserves that are normally provided by provincial and municipal governments off reserves. It is not always evident whether the federal government is committed to [funding] services on reserves of the same range and quality as those provided to other communities across Canada.

And,

The federal government has often developed programs to support First Nations communities without establishing a legislative or regulatory framework for them. Therefore, for First Nations living on reserves, there is no legislation supporting programs in important areas such as education, health, and drinking water. Instead, the federal government has developed programs and services for First Nations on the basis of policy. As a result, the services delivered under these programs are not always well defined and there is confusion about federal responsibility for funding them adequately.

The Auditor General is saying that the federal government has not committed to delivering a set quality or quantity of supports. For example, the federal government has not committed to providing drinking water of the same quality and gallons per person per day as provincial standards require. Instead, its decisions are made “on the basis of policy” i.e. on the basis of the government’s own priorities, which include political considerations.

The Auditor General also noted that most money is provided under contribution agreements which are specific to each First Nation. Many agreements must be renewed yearly and involve a heavy load of paperwork for First Nations. Except for ongoing health and education programs, funds are often delayed until several months into the year they are required, because they are not released until last year’s spending has been scrutinized and the current application reviewed by the government.

A recent change provides a partial remedy. In December 2017 the Minister of Indigenous Services announced that, going forward, First Nations in good financial standing will receive commitments of specified amounts of funding for 10 years into the future, and reduced reporting requirements. Details are being worked out with the Assembly of First Nations and with the First Nations Financial Management Board (FNFMB).

In 2011 the Auditor General noted that the federal government does not have clearly stated goals regarding Indigenous welfare, and thus no way to evaluate its own performance. There had been and still was a lack of coordination among the various federal Departments involved with Indigenous communities, but coordination was improving. One key problem was that INAC did not believe itself to be responsible for service and delivery; but only for funding. Meanwhile, most reserves were small and did not have the expertise needed to oversee service and delivery, nor did they typically have school boards, health boards, and other regional authorities to manage service and delivery.

In 2011 the Auditor General expressed frustration at the government’s lack of progress since previous audits, noting the following (verbatim):

- Education. In 2000 and 2004, our reports identified a gap between the secondary school completion rates for First Nations people on reserves and the rates for other Canadians.

- Water. In 2005, we reported the lack of a legislative regime to ensure that water quality on reserves met the Guidelines for Canadian Drinking Water Quality, despite the existence of such a regime in every province and territory.

- Housing. In 2003, we reported a significant housing shortage on reserves and the need for major renovations of about 44 percent of existing housing because of problems such as mold contamination. In 2006, we reported unsatisfactory progress in addressing the problem of mold.

- Child and family services. In 2008, we reported that First Nations children were eight times more likely to be removed from their homes than other Canadian children.

- Land claim agreements. In 2003 and 2007, we reported that the federal government was not implementing all of its obligations under land claim agreements and was not living up to the spirit and intent of the agreements.

- Reporting requirements. In 2002, we noted that First Nations communities, many of them having fewer than 500 members, had to fill out an excessive number of reports for INAC each year, and that many of the reports were never reviewed and served no purpose.

The Auditor General then went through each of these categories and noted how the Federal government had addressed the issues. The overall conclusion was that, while some steps had been taken to adopt the Auditor General’s recommendations:

“…INAC, the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation, and Health Canada have not made satisfactory progress in implementing several of our recommendations.

…In some cases, conditions have worsened since our earlier audits: the education gap has widened, the shortage of adequate housing on reserves has become more acute, and administrative reporting requirements have become more onerous.”

The lack of progress in adopting the Auditor General’s recommendations has been tolerated by Canadian voters. For example, in 2017 the Auditor General expressed his frustration[7] that the general public doesn’t care enough that First Nations’ needs are not being met. He used as an example the oral health program run by the federal government for First Nations and Inuit at a cost of $200 million per year.

The goal of the oral health program is to “manage” the payments for dental services, but there is no strategy to improve the level of oral health in Indigenous communities, which is well below the level of oral health in non-Indigenous communities. The only news network interested in discussing his audit of the oral health program, released the previous week, was the Aboriginal Peoples Television Network.

In our next chapter we examine the specific case of federal spending on child welfare and healthcare.

- Government of Canada (2020e) ↵

- From “The Adventure of the Copper Beeches” by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle ↵

- The 2016 number for reserves comes from the Parliamentary Budget Office (2017). The 2019 number for reserves comes from the financial statements of Indigenous Services Canada (ISC) as detailed in the first pie chart later in this chapter. From the 9,787,946, 287 spent by Indigenous Services Canada (ISC) in 2018-9 we subtract 1,799,071,172 in non-transfers (presumably salaries, transportation and overhead for ISC) and 51,241,658 in urban programming as well as 233,731,994 which is one-tenth of education spending, our estimate of education spending off-reserve. This leaves us with 7,703,901,463 which is $22,588 per person. ↵

- This amount is calculated by taking total CIRNAC spending and subtracting spending on non-transfers (presumably salaries etc.), the Federal Interlocutor Program for non-Status persons, Northern Contaminated Sites, the Canadian High Arctic Research Station, and 60% of the spending on programs which don’t just apply to Status persons on reserve: Land, Natural Resources and Environmental Management; Economic Development Capacity; Northern and Arctic Governance; Nutrition North; Consultation and Policy Development; Climate Change Adaptation; Basic Organizational Capacity; Individual Affairs; Northern and Arctic Environmental Sustainability; and Northern Regulatory and Legislative Frameworks. ↵

- GC InfoBase - Report Builder - Expenditures and Planned Spending by Program - Government of Canada ↵

- Family and Child Services of Frontenac, Lennox and Addington (2020) ↵

- Galloway (2017) ↵

The term "fiscal" is used to discuss the government's spending or tax revenue, the two key components of a government's budget.

Governance refers not to the system of government but to the legal, procedural, and cultural infrastructure built around it to make sure it works as it should and that it cannot be perverted by powerful individuals or interest groups.

The Auditor General of Canada serves to impartially evaluate the efficacy of the federal government's spending and the accuracy of its financial statements.