The Modern Treaty Era

We know that by 1900, First Nations on the Plains were locked down on Reserves. First Nations in Eastern Canada that occupied areas protected by earlier treaties were also subjected to the reserve system and the Indian Act. The Métis as yet had no land base.

What about other Indigenous groups in Canada? The Cree in northwestern Quebec, the Inuit, and most of the First Nations of British Columbia and the Yukon – these groups had never signed any treaties. They would eventually negotiate what we call modern treaties.

Modern treaties

- have been negotiated with property legal representation for the Indigenous party

- override most articles of the Indian Act

- include self-government agreements

- usually increase the size of reserves

- extend partial control of some of the Indigenous group’s traditional territory to the Indigenous group

- usually cede complete control of part of the Indigenous group’s traditional territory to the government of Canada or to a province of Canada

- provide financial compensation for the ceded lands

- provide money to help implement the treaty’s provisions

- promise ongoing support for health, education, and other critical expenditures

- specify what tax exemptions will or will not apply on the lands controlled by the Indigenous group

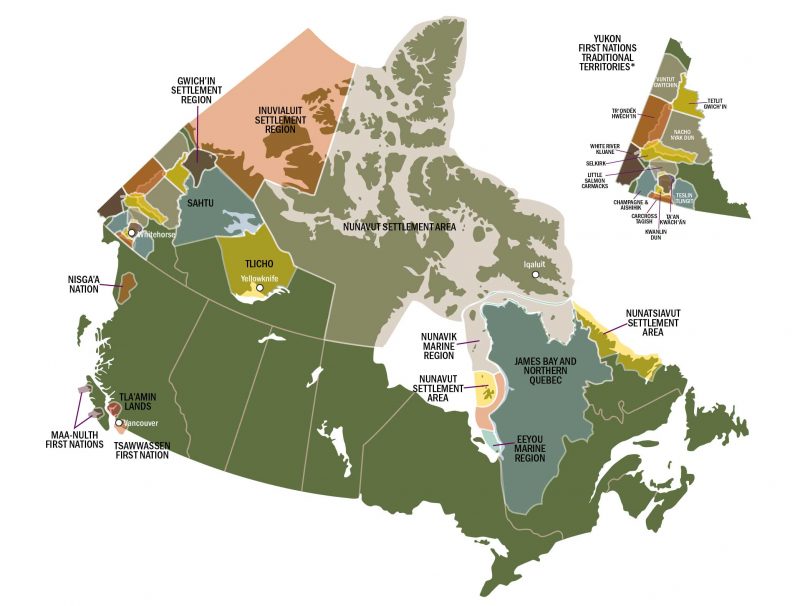

In 2022 there were 26 modern treaties in existence, covering about 35% of Canada’s landbase (NIEDB et al., 2022).

Let’s go back in history and trace the birth of these modern treaties.

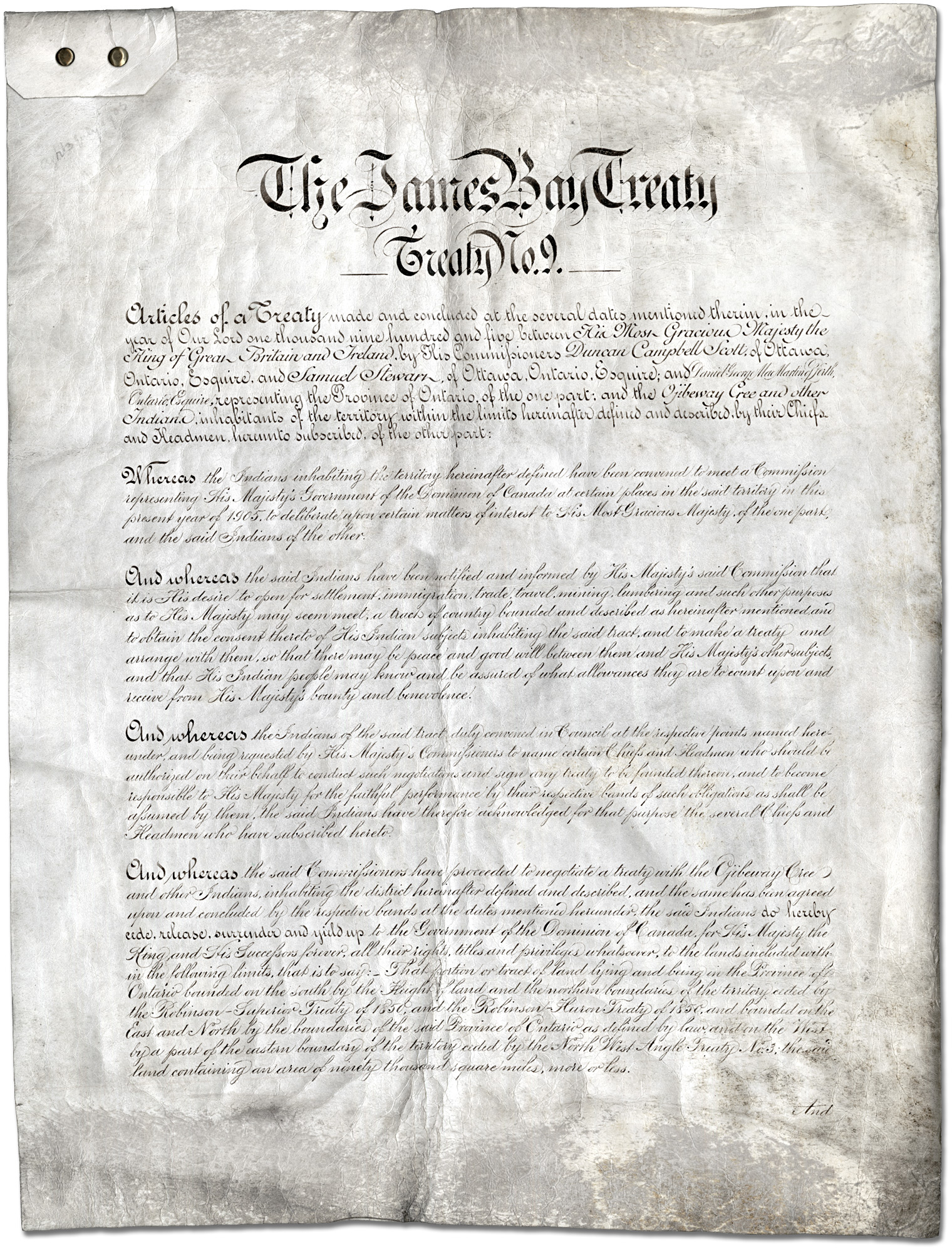

The Last of the Numbered Treaties

The Cree on the Ontario side of Hudson Bay and James Bay, being very aware of the steady influx of settlers competing with them in hunting, trapping, and fishing, signed Treaties 5 and 9 in 1905. At this time the governments of Canada and Ontario were interested in securing land for settlers, mining, and railways. Treaty 9 was extended in 1929, doubling the territory ceded. Treaty 9 covers about two-thirds of Ontario.

Treaties 5 and 9 were the old-style treaties, where it is unclear whether First Nations fully understood the degree to which they would be limited to their reserves. Treaty 9 (1905) is like many early treaties in that the Cree believed they would be able to continue hunting, trapping and fishing in the area ceded.[1]

“Missabay, the recognized chief of the band, then spoke, expressing the fear of the Indians that, if they signed the treaty, they would be compelled to reside upon the reserve to be set apart for them, and would be deprived of the fishing and hunting privileges which they now enjoy. On being informed that their fears in regard to both these matters were groundless, as their present manner of making their livelihood would in no way be interfered with, the Indians talked the matter over among themselves, and then asked to be given till the following day to prepare their reply.” [2]

But the written Treaty contained a massive loophole:

“And His Majesty the King hereby agrees with the said Indians that they shall have the right to pursue their usual vocations of hunting, trapping and fishing throughout the tract surrendered as heretofore described, subject to such regulations as may from time to time be made by the government of the country, acting under the authority of His Majesty, and saving and excepting such tracts as may be required or taken up from time to time for settlement, mining, lumbering, trading or other purposes.”

It is relevant that, of 76 Indigenous signatories to Treaty 9 (1905 version), 54 made their signatures using a mark, 20 used Cree syllabics, and 2 wrote in English. The Cree had no legal representation, and in at least one case the interpreter may not have been able to speak the local dialect.[3]

Between 1929 (the extension to Treaty 9) and 1975 (the first modern treaty) there were no treaties made. What happened during that 46-year period that could explain how treaties went from short, imprecise documents to massive legal tomes? Explore these changes more fully on your own.

- Increased literacy in English of Indigenous persons

- Greater sense of responsibility for social welfare on part of citizens and government

- 1951 Indian Act amendments removing prohibition on Indians hiring lawyers to argue with the Crown

- 1960 right of Status persons and Inuit to vote

- Civil Rights movements in the United States and Canada

- American Indian Movement (AIM)

- Supreme Court rulings in support of Aboriginal title

The First Modern Treaty

No treaties were made on the Quebec side of James Bay and Hudson Bay at the time of Treaties 5 and 9, but as time went by, pressures on traditional Cree and Inuit territory became more intense.

Then, in the early 1970s, the Quebec government announced plans for a giant hydroelectric project on Cree territory – four dams on the La Grande River, plus eighteen spillways and control structures, along with 130 kilometers of dykes.

At this point the Cree of northern Quebec, numbering about 10,000, organized themselves as a nation on People’s Land or Eeyou Istchee. Eeyou Istechee is represented by the Grand Council of the Crees.

In 1973, the Supreme Court made a pivotal ruling in a case called R. v. Calder. It agreed with the plaintiff, a Nisga’a man named Frank Calder, that First Nations at the time of European contact had had title to their land. If, as in Quebec in 1973, there was land regarding which no treaty had ever been made with settlers, then it was possible that First Nations still had Aboriginal title to that land.

Likely encouraged by this ruling, the Grand Council of the Crees took the Quebec government to court over the proposed hydroelectric project.

Carlson (2008) writes,

“What [the Cree] were bewildered by was a system of knowledge and a concept of nature that would use the power of technology to create this particular kind of dam. They were bewildered by a definition of progress that their land be used in this way, by a definition of progress that disregarded the totality of their land in order to reshape it for strictly human use.” (p. 228)

The Grand Council of the Crees argued that their Aboriginal title had never been extinguished by a treaty.

The Quebec court agreed that the balance of convenience should be with the Cree who had been using the land since time immemorial, giving the Cree the leverage they needed to get Quebec and Canada to the negotiating table. The resulting James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement (JBNQA), signed in 1975, became the first modern treaty.

The Manuel-Derrickson Critique:

While the JBNQA and modern treaties in general are an improvement over earlier treaties, Arthur Manuel and Grand Chief Ronald Derrickson have argued that modern treaties too are seriously flawed. In their book The Reconciliation Manifesto (2017), Manuel and Derrickson argue that the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement (JBNQA) was cut from the same cloth as earlier treaties because it required the Cree to give up land rights to most of their territory, and left them with only partial control of the remaining territory. They write:

“After the UN criticized Canada for requiring the Cree to give up title to the land in the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement (1975), the government has continued to require the same, but calls it “modification” or “surrender and grant back” or, recently, “reconciliation”. They still require extinguishment of our title as the first principle of any land deal.”

The 2022 National Indigenous Economic Strategy calls on the government to eliminate this practice.

Details of the JBNQA:

In return for allowing Quebec to build the La Grande hydroelectric project, the Cree received $130 million dollars ($13,000 per person) and the right to a regional government called the Cree Regional Authority.

Inuit communities along the Quebec coast of James Bay, Hudson Bay, and Ungava Bay were also included in the agreement, receiving financial compensation and a regional government named Kativik.

The Cree Regional Authority and Kativik will receive ongoing federal transfers to help them oversee health and social services delivery, education, and local law enforcement. The funding for health care comes from Quebec and includes some health services not included in provincial programs for the general public. The funding for Education comes from both Quebec and Canada. The regional school boards can, in cooperation with the province of Quebec, decide on alternative school calendars, teacher qualifications, courses, textbooks, and programs. The primary language of instruction is Cree or Inuktitut.

As indicated in light green on the map of Quebec at left, the JBNQA covers more than a million square kilometres of western and north-central Quebec, two-thirds of the province of Quebec. JBNQA land is shown in the darkest green colour on the map at right. It includes the Inuit territory now known as Nunavik.

The yellow area in south central Quebec and a little further east indicates the traditional territory of the Innu, formerly known as the Montagnais. No treaties have been made with the Innu as of 2023.

The JBNQA divides the subject lands into three categories. On Category III lands (the vast majority), both Indigenous and non-Indigenous persons may trap and fish for personal or commercial purposes, but some species are reserved for Indigenous use only. Indigenous people may hunt for personal or community use, without a permit. Non-Indigenous people require permits.

On Category II lands, only Indigenous persons may trap and fish for personal or commercial purposes. They may hunt for personal or community use.

Category I lands are for the exclusive use of the Cree (or Inuit). They represent about 1% of the total lands in the JBNQA area, and coincide with where the Cree and Inuit communities are located. Category I lands can only be hunted, trapped or fished by Indigenous people. Again, hunting can only be for personal or community use. On Category I lands, Indigenous people may run or own commercial forestry operations, subject to provincial government approval.

Quebec retains reversionary title[4] to all lands, even Category I lands. Quebec retains forestry rights on Category II and III lands, and ownership of all mineral and subsurface resources in the entire JBNQA area. This was walked back a bit in 2002, when a new agreement between the Grand Council of the Crees and the province of Quebec was signed. La Paix des Braves gives the Cree joint management of forestry, mining, and hydroelectric projects on Category II and III lands, as well as a share of the revenues into the future.

The representative of the Premier of Quebec made these comments in 1975:

“Now to see the Category I lands in their proper perspective, it must be realized that they represent a tiny proportion of the whole territory. Approximately 3,250 square miles are to be allocated to the use of the Inuit, and 2,158 square miles to the use of the Crees. Thus, although these lands are vital to the native peoples and they constitute an essential element of the Quebec Government’s policy of protecting their traditional economy and culture, you will agree that they are of minimal importance in relation to the total economy of Quebec.”

Successive additions to the agreement have given more funds to both the Cree Regional Authority and to Kativik as more dams have been added to the hydroelectric project.

East versus West:

We have learned that the Cree of northern Quebec have the JBNQA and La Paix des Braves, while the Cree of northern Ontario have Treaties 5 and 9. Which group has fared better?

Generally, the Cree of Treaties 5 and 9 have not been compensated for hydroelectric projects along their waterways. They also have some of the poorest reserves in the nation, such as Attawapiskat and Kashechewan. Recall the Community Well-Being Index[5] which we discussed in Chapter 2. In 2011, only one community on the Ontario side of James Bay provided sufficient data – and it scored in the 1-49 category.

By contrast, on the Quebec side of James Bay, four communities provided enough data to form a score – and scored between 60-69. (The average First Nation community in Canada scored 59; the average municipality scored 79.)

Things have improved in Ontario since then. In 2016, all five communities hugging the Ontario shore of James Bay and Hudson Bay reported data, and the scores ranged between 48 and 67. (On the Quebec side, scores continued to range between 60 and 68.)[6].

As the legal landscape changes in favour of First Nations, giving them Aboriginal Title to traditional lands, Ontario First Nations are asserting their rights. As reported by Heaps (2019), the Moose Cree helped cancel plans to build the Smokey Falls Hydro Station. Ontario Power Generation negotiated with the Moose Cree for four years before doubling electricity generation along the Lower Mattagami River, with the result that the Moose Cree were assisted to buy a 25% share in the Mattagami upgrade. Ontario Power Generation lent them part of the necessary money at regular commercial interest rates, and the rest of the money was lent by Ontario’s Aboriginal Loan Guarantee Program.

The Twentieth Century and the Inuit

The Inuit lifestyle was largely unchanged by contact with non-Indigenous people until the 1850s, when permanent whaling stations were established on the shores of northern Hudson Bay. European epidemic diseases began to spread. Alcohol, the exploitation of women for sex, and sexually transmitted diseases took a heavy toll.

Overhunting of whales became critical, so that after 1910 whaling was replaced with buying fox pelts from the Inuit. The allure of trapping to acquire European trade goods motivated some Inuit to branch out on their own to manage traplines, in areas not necessarily ideal for hunting food. Guns were a mixed blessing, making hunting easier but facilitating the overhunting of caribou and musk oxen.

Fur collection stations along the coast became places where Inuit art and crafts were traded, including sculptures of soapstone and ivory. Like fur, these beautiful objects are small and lightweight relative to their market value, so they can be profitably traded south. In the early 1950s, artist James Houston began to promote Inuit Art with the help of the federal government and the Hudson Bay Company. Inuit sculpture and printmaking are now thriving industries.

Until the end of the Second World War, neither the federal government nor provincial governments had had much to do with the Inuit. White settlers tended to form their own, separate communities in the Far North. Missionaries, clergy, traders, and entrepreneurs from the south were more likely than others to integrate into Inuit communities, but they comprised a small minority.

During the 1950s, Canada partnered with the United States to install research and communications stations, radar lines, and airfields across the Arctic. The federal government also turned its attention to developing the northern resource economy and facilitating mining. It determined to bring modern amenities and services to communities in the north.

Programs such as social assistance, medical care, subsidized housing, and education were offered; In fact, education of children became mandatory and required parents to settle in one place. Unfortunately, Children and parents were sometimes separated for long periods of time for schooling or medical treatment.

Settlement interfered with traditional hunting and led to the Inuit (and also the Innu and other groups) becoming clustered around towns where government services were provided. In some cases, the government forced communities to locate to particular areas which would help establish Canada’s sovereignty in the North.

“Many of the communities that emerged or started to grow during the 1950s and 1960s were developed in places that Indigenous peoples had used in their annual migrations. Some, however, brought together people who had little to do with one another historically, meaning that building a “community” took some time to achieve… In some instances, such as at Grise Ford and Resolute Bay, communities were created through dramatic and harsh relocations, a particular challenge in the subsequent building of resilient, confident communities.”[7]

Settlement also intensified the presence of sled dogs. Dogs were used for transportation and hunting during the winter, and were fed from the meat that was hunted. But in summer they might be less well fed, and let loose to look for their own food. Stray dogs have been a problem in remote communities; in 2010 a child was killed by resident dogs in Canoe Lake First Nation.

During the 50s, 60s, and 70s, hundreds if not thousands of dogs considered to be suffering or dangerous were shot by officials or RCMP officers, traumatizing Inuit families. This was done in what appeared to the Inuit to be a capricious and high-handed manner, without explanation or negotiation. It seemed part of a campaign to erase their traditional way of life.

The Qikiqtani Truth Commission, tasked with documenting the harms experienced by the Inuit after 1950, published its “QTC Final Report: achieving saimaqatigiingniq” in 2013.

Inuit modern treaties

Beginning in 1975, all of Inuit Nunangat has been covered with modern treaties.

As you know, the Inuit of northern Quebec had been included in the first modern treaty, the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement. The Inuit region covered by JBNQA is named Nunavik. All residents of Nunavik can vote in elections which determine the leaders of various agencies. Nunavik also has a seat in the Quebec Legislative Assembly.

The JBNQA provided funds for Nunavik’s economic development through a new company called the Makivik Corporation.

The second Modern Treaty also involved Inuit. It covers the region known as Inuvialuit, the westernmost Inuit region.

Formerly part of the North West Territories, Inuvialuit was returned to Inuit control in 1984, giving them the complete slate of resource rights, subject to sharing wildlife and environmental management decisions with the federal government. Inuvialuit has a public government which represents all residents of whatever ancestry. It also has Inuvialuit Regional Corporation to actualize Inuvialuit self-government of their health, education, language revitalization, economic development, and other concerns.

In 1999 the third Inuit region, Nunavut, was defined, also from the North West Territories. The Inuit of Nunavut chose to have a public rather than Indigenous-only government, with nineteen members of parliament, each running independent of any political party. 18% of Nunavut land has been transferred to the Inuit specifically, not the Nunavut government, through the new corporation Nunavut Tunngavik Inc.(NTI). NTI gets all resource extraction taxes (known as royalties) for extraction done on its land, and also a portion of the royalties arising from extraction done elsewhere in Nunavut. NTI has also been given cash as part of the 1993 Nunavut Land Claims Agreement.

Unfortunately, most of the land in Nunavut which is not owned by the Inuit through NTI is still owned by the federal government, so the government of Nunavut gets very little income from resource royalties. Courchene (2018) argues that if it could earn royalties, it would not need the large federal transfers that it now receives, approximately $40,000 per person in 2016.

In 2005 the fourth and final Inuit region was created, Nunatsiavut, along the coastline of northern Quebec and northern Labrador. In Nunatsiavut only Inuit can be elected to government. There are seven constituencies – two of which are outside of Nunatsiavut! One is a town in central Labrador, and the other constituency consists of all Nunatsiavut citizens who reside in the rest of Canada. The Nunatsiavut government collects property taxes, personal income taxes, resource royalties, and a portion of federal excise taxes (alcohol, cigarettes, gasoline); however, federal transfers are an even larger source of revenues for Nunatsiavut.

The Twentieth Century in British Columbia and the Yukon

For most of the twentieth century, British Columbia (BC) and the Yukon were largely devoid of treaties.

Treaties were made on Vancouver Island, BC during the 1850s. The Hudson’s Bay Company had been given the right to trade there on the condition that it would welcome settlers. It negotiated the Douglas Treaties with the First Nations on Vancouver Island to facilitate settlement. But these were not modern treaties; these were old-style treaties without modern legal representation of First Nations.

The Colony of British Columbia was established on the mainland in 1858 in response to a rush to mine gold along the Fraser River. This gold rush brought thousands of American and Canadian miners into the BC interior and north. The miners and their retinue began settling on the most favourable agricultural land. According to the Supreme Court (2018), this prompted several First Nations Chiefs to consider armed conflict. However, Governor Douglas assured them that their villages and fields would be noted and protected.

In 1860 Douglas issued a Proclamation that settlers could acquire un-surveyed land, but only if it was not part of an existing or proposed town, a gold mining site or an “Indian reserve or settlement”.

Sadly, this Proclamation was ignored, and White settlement was favoured. A law in 1866 under governor Frederick Seymour specified that no Indigenous person could pre-empt or buy land, except with special permission from the governor. While some lands were promised to First Nations, these were not formally surveyed or backed by legal documents, and were gradually eroded by settlement or even – in for example the case of the T’exelc – completely eliminated.

No treaties were negotiated with mainland British Columbia First Nations except Treaty 8 (1899). Treaty 8 covers parts of northeastern BC and Alberta. It was arranged in the context of the Klondike Gold Rush.

Generally, BC First Nations on the mainland were displaced and confined to areas which were by no means safe from further encroachment or division. For example,

“Beginning in the late 1870s with the establishment of the Kamloops-Okanagan [Indian] Agency, …the Secwépemc nation was split into agencies that combined some Secwépemc communities with Syilx, others with Nlaka’pamux and Lillooet, and Northern Secwépemc with Tsilhqot’in and Carrier. Indian agents began to assert their control over individual communities and continued the nucleation of the nation into bands and reserves.”[8]

The literal fencing out of the Secwépemc Nations from the places they depended on for fish, roots, berries, meat, game, meetings, rituals and so forth is compellingly relayed in The Unfolding of Dispossession, chapter twelve of Secwépemc People, Land and Laws (Ignace & Ignace, 2018).

In 2018 the Supreme Court of Canada (R. v. Williams Lake Indian Band) ruled in favour of the T’exelc, whose village – at what is now downtown Williams Lake, BC – and traditional lands were entirely taken over by settlers. The Court ruled that it had been Canada’s responsibility to reverse this expropriation even though it occurred before Confederation.

First Nations leaders actively resisted expropriation by appealing to the government. When Prime Minister Wilfred Laurier visited Kamloops in 1910, Secwépemc (Shuswap), Nlaka’pamux (Thompson), and Syilx (Okanagan) Chiefs, they delivered a document now known as the “Laurier Memorial”. It included these lines:

What have we received for our good faith, friendliness and patience? Gradually as the whites of this country became more and more powerful, and we less and less powerful, they little by little changed their policy towards us, and commenced to put restrictions on us. Their government or chiefs have taken every advantage of our friendliness, weakness and ignorance to impose on us in every way. They treat us as subjects without any agreement to that effect, and force their laws on us without our consent and irrespective of whether they are good for us or not. They say they have authority over us. They have broken down our old laws and customs (no matter how good) by which we regulated ourselves. They laugh at our chiefs and brush them aside. Minor affairs amongst ourselves, which do not affect them in the least, and which we can easily settle better than they can, they drag into their courts. They enforce their own laws one way for the rich white man, one way for the poor white, and yet another for the Indian. They have knocked down (the same as) the posts of all the Indian tribes. They say there are no lines, except what they make. They have taken possession of all the Indian country and claim it as their own. Just the same as taking the “house” or “ranch” and, therefore, the life of every Indian tribe into their possession. They have never consulted us in any of these matters, nor made any agreement, “nor”

signed “any” papers with us. They ‘have stolen our lands and everything on them’ and continue to use ‘same’ for their ‘own’ purposes. They treat us as less than children and allow us ‘no say’ in anything. They say the Indians know nothing, and own nothing, yet their power and wealth has come from our belongings. The queen’s law which we believe guaranteed us our rights, the B.C. government has trampled underfoot. This is how our guests have treated us—the brothers we received hospitably in our house.

Because of the relentless encroachment of settlers, pressure on the First Nations was intense. There is evidence that potlatches became ever more competitive and extravagant, with Chiefs actually breaking coppers and burning whole canoes and boxes of eulachon oil during the potlatch (McMillan and Yellowhorn 2004, p. 209). The destruction of wealth at these later potlatches may be one reason that the potlatch was banned under the Indian Act between 1885 and 1951.

Despite cultural bans, much cultural knowledge has been retained, helped by the fact that colonization occurred much later for BC First Nations than for eastern First Nations.

BC First Nations have become leading advocates of First Nation sovereignty. For example, in the daring move described in our Foreword, the BC Union of Indian Chiefs for a time refused federal funding and federal supervision. The same spirit of resistance fueled the Chiefs to participate in several lawsuits that have dramatically changed the legal and political landscape for Indigenous Peoples.

Perhaps the most important legal change instigated by BC First Nations, one that paved the way for many others, was R. v. Calder (1973). As mentioned above, Canada’s Supreme Court ruled that Aboriginal Title is a valid concept in Canadian law and, in parts of Canada where treaties have not been made, Aboriginal Title could still exist. As Courchene (2018) expounds, this completely contradicted the view of then Prime Minister Trudeau whose 1969 White Paper would have erased distinctions between Indigenous and other Canadians. The federal government immediately took note of this ruling and opened the Office of Native Land Claims the next year, 1974. This must have helped bring about the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement (1975).

In 1982, Canada sought to become completely independent of Great Britain by means of an updatedconstitution. Some Indigenous groups opposed this, fearing that Canada without Britain would not be as invested in a nation-to-nation relationship with Indigenous people. Others saw a new constitution as an opportunity to secure recognition of Aboriginal rights. Provinces, especially Quebec, and other interest groups also vied for greater recognition and influence. In 1982, without First Nations, Inuit or Métis having any vote, the new Constitution Act and accompanying Charter of Rights and Freedoms were passed by parliament.

Section 35 of the new constitution contains clauses affirming Aboriginal and Treaty Rights, including rights derived from present and future land claims.

Though the new constitution affirms Aboriginal Rights, details are lacking. Very little progress was being made with respect to land claims or self-government.

Finally, in 1993, a modern treaty was negotiated in the West – the Yukon First Nations Agreements, covering 12 of Yukon’s 14 First Nations. The First Nations now control citizenship, adoption, custody, education, dispute resolution, administration of justice in accordance with Yukon law, business licensing, local taxation, environmental protection, and resource extraction on their lands. They received financial compensation, some of which was to compensate them for agreeing to collect federal income taxes so that both native and non-native residents will be taxed the same way.

What about the Nisga’a in British Columbia, whose land rights aspirations had led to R. v. Calder in the first place? In 2000 their turn came. The Nisga’a Treaty Agreement, the first Modern Treaty in British Columbia, returned to the Nisga’a about two thousand square kilometres, 8% of the territory claimed. Existing non-Nisga’a owners of lands were allowed to keep their properties. The Nisga’a land is for the Nisga’a to manage, mine or sell; some provincial or federal industrial standards, harvesting limits, and environmental laws apply. Remarkably, Nisga’a village governments may allocate land to Nisga’a citizens in fee simple, which means the new owners are free to sell the land to anyone, even to non-Nisga’a or non-Indigenous buyers. We discuss fee simple land ownership in Chapter 24. The Nisga’a must pay provincial and federal income taxes on income earned on these lands. The Nisga’a administer their communities themselves and have their own police force to keep the peace according to provincial and federal laws. They have also received $190,000,000 in installments.

Under this treaty, said Frank Calder, “we will no longer be wards of the state. We will no longer be beggars in our own lands. We will own our own lands, which now far exceed the postage stamp reserves that were begrudgingly set aside for us by colonial governments. We will once again govern ourselves by our institutions, in the context of Canadian law. We will be allowed to make our own mistakes, to savour our own victories, to stand on our own feet.”[9]

Subsequent modern treaties within British Columbia include the Westbank First Nation Self-government Agreement (2005), the Tsawwassen First Nation Final Agreement (2009), and the Maa-Nulth First Nations Final Agreement (2011).

In the absence of a modern treaty: amendments to the Indian Act

BC First Nations have been economically innovative. After the resistance of the BC Union of Indian Chiefs, Kamloops Chief Manny Jules and others began to engage with one another and the federal government to bypass the Indian Act in certain respects. Because of their efforts, First Nations still under the Indian Act can subscribe to the following:

- The Kamloops Amendment to the Indian Act (1988). Affirms that reserve lands leased to non-Indigenous people are still part of a Nation’s reserve. Permits First Nations to apply property tax to band members and non band-member leaseholders.

- The First Nations Land Management Act (1999). Participating First Nations have the right to manage their own lands and set up land ownership rules.

- The First Nations Goods and Services Tax Act (2003). Allows First Nations to implement their own sales tax.

- The First Nations Fiscal Management Act (2005). Establishes the First Nations Tax Commission, the First Nations Financial Management Board, and the First Nations Finance Authority to assist First Nations in collecting taxes, becoming credit-worthy, and obtaining loans.

The possibilities afforded by these new Acts will be discussed in later chapters.

Métis Settlements

The Métis do not have any treaties per se with the federal government, whether historic or modern treaties. In 2023, the Métis Nation of Alberta, the Métis Nation of Ontario, and the Métis Nation – Saskatchewan each signed a self-government agreement with the federal government. This gives them the right to determine their own membership, choose their own leaders, and negotiate with the government. What implications there will be for child welfare, education, and other matters remains to be worked out.

Eight Métis communities in Alberta have achieved official recognition from the province of Alberta under the Métis Settlement Act (1990). It specifies that a General Council, funded by the province, will represent the residents and will manage the money paid into its Consolidated Fund by the province. Between 1997 and 2007, the Métis Settlements General Council was managing $10 million annually from the government in accordance with the Métis Settlements Accord Implementation Act.[10]

The General Council owns all Métis Settlement lands in “fee simple”, which means full ownership of land including the right to develop, rent, or sell it. However, such decisions must be made as a community.

Although the Métis do not have ownership of minerals or oil and gas on their settlements, they have a Co-Management Agreement with the Province which allows them to negotiate royalties for resource extraction on their lands and become part or full owners in mineral companies.

In 2013, the Council negotiated with the Province to increase its potential ownership stakes in mineral companies and to obtain 85 million dollars from the Province for improved governance, education, employment opportunities, policing, and other measures. [11]

Similarly, many First Nations in British Columbia which do not yet have a treaty or are not interested in pursuing one have signed Forestry and other agreements with that province.

In our next Chapter we’ll summarize how various Indigenous communities are faring financially, before moving on to consider their funding, governance, sources of capital, and business development in more detail.

- http://mushkegowuk.com/documents/jamesbaytreaty9_realoralagreement.pdf ↵

- James (1986) relying on a 1964 federal publication entitled James Bay Treaty: Treaty Number Nine ↵

- James (1986), between footnotes 209 and 210 ↵

- Reversionary Title is default ownership should the current occupant of the land die or be unable to occupy the land. ↵

- Indigenous Services Canada (June 2019) ↵

- Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada (2011-2015) ↵

- MacPherson (2015) ↵

- Ignace and Ignace (2017), p. 456 ↵

- originally quoted in Mark Hume (2005) ↵

- Province of Alberta (2019) ↵

- Province of Alberta (2020) ↵

Modern treaties are treaties negotiated in or after 1975. They were negotiated with proper legal representation of Indigenous peoples and give Indigenous peoples some self-government powers. Other features of modern treaties are discussed in Chapter 15.

Aboriginal title is the land ownership rights of Indigenous people due to the fact that they were there first and that they did not sign any treaties giving up their land. For details, see chapter 25.

We use the word expropriation to mean taking someone's land without their permission, with the amount of compensation - if any - being determined by the expropriator's government, if that government is able and willing to enforce compensation.

The founding document of Canada. The first edition, dated 1867, was revised in 1982.

Fee simple is the property right normally associated with home or property ownership in Canada. People living on reserves do not own land in fee simple. For details, see Chapter 24.