Economies prior to the late 20th Century

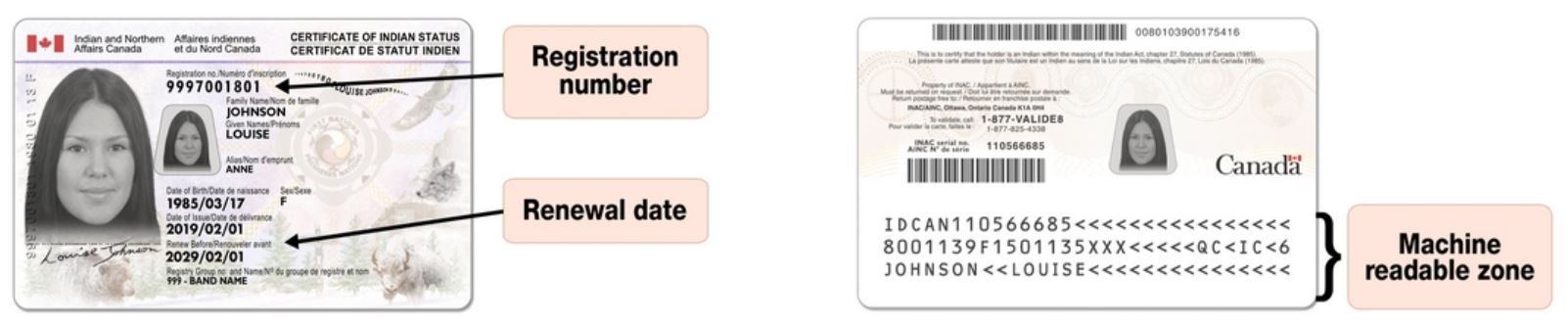

As we have learned, the Indian Act applies to First Nations people who signed treaties with the federal government or who were on another occasion recorded as belonging to a First Nation Band, and to their descendants – if the descendants’ Indigenous ancestry is not too diluted with non-Indigenous ancestry.

The federal government maintains the Status registry, deciding by its own rules who is Indian enough for Status benefits.

How can Status be lost?

For many years, roughly 1830-1960, it was the aim of the Canadian government to reduce the number of people with Status by removing Status from women who married non-Status men, and by removing Status from men in through a process known as enfranchisement.

Enfranchisement was automatic if a person became a doctor, lawyer, or Christian minister, or if he (or she) otherwise earned a university degree. Leaving the reserve to fight for Canada in WWI or WWII could also require or result in a loss of Indian Status. Anyone living outside Canada for more than 5 years without permission was enfranchised. A man who became enfranchised would cause his wife and children to lose their Status also. A portion of the band’s assets would be transferred to him.[1]

Since 1869, Status women who married anyone other than a Status man lost their status, but white women who married Status men became Status women.

In 1951, a restriction for men was added to the Indian Act: if the man’s mother had been non-Status, and if his wife was non-Status, then the husband’s status would not be enough to give his child status after age of 21. This new rule was not retroactive; it only applied to children whose parents married after the amendment was passed. Note that the sex discrimination was not eliminated. If a woman married out, she and her children lost Status immediately. If a man married out, and his son also married out, the grandchildren would lose Status after age 21.

In 1951, a restriction for men was added to the Indian Act: if the man’s mother had been non-Status, and if his wife was non-Status, then the husband’s status would not be enough to give his child status after age of 21. This new rule was not retroactive; it only applied to children whose parents married after the amendment was passed. Note that the sex discrimination was not eliminated. If a woman married out, she and her children lost Status immediately. If a man married out, and his son also married out, the grandchildren would lose Status after age 21.

One important consequence of losing Status is that, depending on the Band’s wishes, the person might lose their right to live on reserve. Federal funding has been in proportion to the number of Status people living on reserve, and non-Status residents are sometimes resented for using the scarce resources on reserve.

After years of Indigenous litigation against the government, in Canada and before the United Nations, the federal government was forced to undo this sex discrimination with Bills C-31 (1985) and S-31 (2017, in force 2019). These pieces of legislation amend the Indian Act so that:

- There is no more enfranchisement. A Status person can never lose their status.

- Status women who married non-Status men after 1951 (Bill C-31) or 1869-1951 (Bill S-31) regain their Status. This affects the status of their descendants.

- Children born after 1951 to a Status parent and a non-Status parent have Status, but it is only half-Status in the sense that, if they also marry a non-Status person when they become adults, their children will have no Status. This is the “second generation cut-off rule.”

- The children of two half-Status persons will have full status.

- The children of a half-Status person and a full Status person will have full status.

- The rights of half-Status or “6(2)” people are identical to those of full-Status or “6(1)” people, except in relation to the second-generation cut-off rule.

To summarize, before 1951 Status women were cut-off upon marrying out, but there was no cut-off rule for men: Status could be maintained through the paternal line. After 1951 the rules were tightened so that men faced a cut-off rule too, though only a second-generation one. Without the higher fertility rates of the Status population, the number of people with status might have declined.

Since Bill C-31 (1985), women now have a second-generation cut-off rule like the men. There is more chance for women to pass on their Status. Furthermore, the children of two people with half-status regain full status. Under this system, can the number of people with status continue to be a robust fraction of the Canadian population?

Maintenance of the Status population over time

It can be shown arithmetically that Bill C-31 allows the Status population to continue into perpetuity. The author has calculated that even if all women are indifferent to the status of their partners so that they have children with 6(1), 6(2), and non-Status men in proportion to those men’s representation in the population, and even if we assume that all couples except for fully non-Status couples have the same net reproductive rate[2] of 0.3% while fully non-Status couples have a higher net reproductive rate of 1.06 to account for immigration of new non-Status people, the fraction of fully Status women, assumed to be 2.07% of Canadian females in year zero, would still be 1.97% of Canadian females after seven generations and 1.78% after twenty-one generations.[3]

Because of Bill C-31, more than 114,000 people successfully reclaimed their Status between 1985 and 2000.

The Parliamentary Budget Office (2017) estimated that about 300,000 new persons will be registered with Status because of Bill S-31; however, application for Status is not straightforward. In March 2023 Marsha McLeod broke the story that applications for Status are complicated, and applications requiring genealogical investigation can take more than two years to be processed. People calling in to Indigenous Services’ Public Enquiries Contact Center for information reported frustrating long wait times.[4]

Band Membership

It is expected that, at most, only 2% of any new S-31 registrants will move to a reserve.[5] Bands with their own membership rules can decide whether they want to accept new members or not. In any case, people with Status are eligible to receive health and education benefits which we discuss in Chapter 17.[6]

As just mentioned, a Band can deprive Status persons of band membership, which means that a Band can have criteria which deny certain people the privilege of living on reserve, owning property on reserve, sharing in Band assets, and voting in Band elections and referenda.[7]

(Children do have the right to live with their parents or guardians on reserve, whether the children are members of the Band or not.)

For example, a Band can remove membership privileges from a Status person who marries a non-Status person. This is happening in the Kanien’kehá:ka Band of Kahnawake, in Quebec.

As of May 2018, About 43% of bands maintain their own membership list.[8]

Economic Rights Associated with Status

A great deal of misinformation exists regarding the rights of Status persons. For example, it is believed that Status people on reserve get free housing, and that Status people off-reserve get free education. The reality is more complex.

Bands receive funding from federal and provincial or territorial governments for housing, education, and health care. However, as we will discuss later in this book, that money apparently does not suffice. The housing, educational achievement, physical health, and dental health of Status persons on reserve is well below average compared with Canadians generally. There is supplementary health and dental care available to Status people living off-reserve, but their health and dental outcomes are also below-average. Bands receive money for post-secondary education for their members whether on or off-reserve, but typically there is not enough money for all post-secondary students to receive adequate funding.

In Chapter 17 we will consider how the government allocates money to Indigenous people, and whether it is sufficient, well targeted, and well spent.

Treaty Payments:

Once a year, each Status Indian is eligible to receive money from the federal government. Don’t hold your breath – these payments are in the five-dollar range. There was never any promise in the Treaties that the annual payments would be adjusted for inflation!

In 2021, the government of Ontario was appealing a recent court victory by First Nations who signed the Robinson-Huron Treaty of 1850. According to the text of this treaty, the First Nations gave up control of a very mineral rich area of Ontario, north of Lake Huron, where the nickel mines of Sudbury are located. In return, the Bands would be entitled to reserves, fishing rights, and hunting rights, and a roughly $2 per person annual payment which could increase based on the income generated by resource extraction. The payment was indeed increased to $4 in 1874, at which level it remains to this day (August 2020).

“The said William Benjamin Robinson, on behalf of Her Majesty, who desires to deal liberally and justly with all her subjects, further promises and agrees, that should the Territory hereby ceded by the parties of the second part at any future period produce such an amount as will enable the Government of this Province, without incurring loss, to increase the annuity hereby secured to them, then and in that case the same shall be augmented from time to time, provided that the amount paid to each individual shall not exceed the sum of one pound Provincial Currency in any one year, or such further sum as Her Majesty may be graciously pleased to order; and provided further that the number of Indians entitled to the benefit of this treaty shall amount to two-thirds of their present number, which is fourteen hundred and twenty-two, to entitle them to claim the full benefit thereof.”[9]

This treaty and its sister treaty, the Robinson-Superior Treaty, set the precedent of an “annuity clause” in which the Crown agreed to pay annuities perpetually in relation to the revenues made by resource extraction on the land in question. The Ontario Superior Court ruled in 2018 that Ontario failed to honour this clause. The outcome of the appeal of the Court’s ruling will have implications for other treaties which have annuity clauses.

Sales Taxes:

Status persons are rumored to pay no taxes. The reality is more complex. Sales tax, excise tax, and income tax may need to be paid.

Status persons must pay GST (the federal sales tax) on goods purchased off-reserve which are not intended for life on a reserve. They must pay PST (provincial sales tax) on all goods purchased off-reserve, except in Ontario. It’s likely that many businesses which are used to waiving the PST will also waive the GST. Some waive the taxes for Status persons as a courtesy or as a way to increase customer loyalty.

To understand the sales tax law, think of reserves as nations outside of Canada. People living in the United States or other countries do not have to pay sales tax on Canadian goods if they are importing the goods to use in their home countries. But tourists in Canada do have to pay sales tax, because they may be using the product or service while they are in Canada. Similarly, Status persons pay sales tax when visiting off-reserve, but don’t pay sales tax when importing products to their homes on reserve.

While Status persons do not have to pay sales tax on reserve, visitors to the reserve are supposed to pay sales tax. In practice, sales tax is not charged to anyone; that is why many non-Indigenous people buy fuel and cigarettes on reserve. We discuss this later.

Some Bands voluntarily charge a sales tax on both Band members and visitors. They do this as part of a self-government agreement, or by signing on to the First Nations Goods and Services Tax Act. The resulting First Nations Goods and Services Tax is equivalent to whatever the federal goods and services tax (GST) or federal portion of the harmonized sales tax (HST) is. The money is returned to the First Nation for its own use.

As Loft (2019) details, Courts have generally allowed Band-owned corporations to pay no sales tax if profits are going to community purposes. Otherwise, incorporated Band-owned businesses with sales over $30,000 must pay GST and PST when they buy goods and services.

Excise Taxes:

Special items like gasoline, cigarettes, cannabis, and alcohol not only incur sales taxes but also incur excise taxes. The excise tax is charged to the producer when the item is sold. The more inelastic is the demand for the product is compared to the supply, the greater the degree to which the producer can pass on the tax by charging more for their product.

The off-brand cigarettes sold on many reserves are unregulated; some may have been smuggled in from the USA. Excise tax was probably not paid to the government when the tobacco was sold to the cigarette manufacturer. Another reason that cigarettes are cheaper on reserve is that sales tax is not charged, even though many of the customers live off-reserve and are not Status Indians. Some Bands, like the Kanien’kehá:ka in Tyendinaga, where cheap cigarettes and gasoline can be purchased, have treaties which they believe exempt them from any and all interference in their business.

In most cases, the revenue collected by the federal government from excise taxes is not shared with Bands. However, the province of Ontario does share a portion of its excise tax revenues with Bands who are monitoring sales and enforcing regulations regarding production, packaging, and advertising. Even when revenues are shared, First Nations may object to sales taxes and excise taxes because these taxes are imposed upon them in violation of their sovereignty and jurisdiction; because they force the Band to act as an arm of an outside government; and because they reduce the price advantage that reserves can offer to off-reserve customers.[10] The issue of taxes on tobacco and other sensitive goods is complicated by the geographic position of the Akwesasne, a reserve which straddles the Canada:US border. A quick internet news search confirms that goods and even human beings have been smuggled through Akwesasne.

The issue of taxes on tobacco and other sensitive goods is complicated by the geographic position of the Akwesasne, a reserve which straddles the Canada:US border. A quick internet news search confirms that goods and even human beings have been smuggled through Akwesasne.

Property Taxes:

Reserve land is exempt from property tax imposed by non-Indigenous governments; however, First Nations governments can choose to impose their own property taxes on reserve land. The Kamloops Amendment gives Bands the right to tax non-member leaseholders, and the First Nations Financial Management Act gives signatory the right to tax Status and non-Status band members. These rights are not automatic; bands must sign on to these agreements, which involves complying with some conditions.

Income Taxes:

The Indian Act has always exempted band members who live on reserve from paying income tax. At the time the Indian Act was first issued, there was no income tax in Canada. Canadians began to pay federal income tax in 1917. Stacia Loft (2019) offered a cynical explanation for why Status persons continued to be exempted from income tax under the Indian Act:

“The government did not expect or intend that Indians would earn an income from the commercial mainstream…”

More benign explanations exist, such as wanting to protect reserve land from seizure for non-payment of taxes, understanding existing treaties to preclude income taxation, and wanting to support income and enterprise on reserve.

Today, Status persons pay no income tax on income earned on reserve, but they must pay income tax on any income earned off reserve that is not related to maintaining Indigenous culture. This includes business income.

Again, Band-owned corporations pay no income if profits are going to the community. Otherwise incorporated Band-owned businesses with sales over $30,000 must pay income tax.

The National Indigenous Economic Development Board (2019; p. 63) has noted that the fact that corporations are not income tax exempt disincentivizes band members or bands from incorporating their businesses, which may impede growth.

It’s also likely that, at the margin of deciding whether or not to join the mainstream economy, the income tax exemption encourages businesses, individuals, and families to stay on the reserve.

Is it unfair that Status persons and unincorporated businesses pay no taxes on reserve income? According to Canada’s Income Tax Act section 149, the following do not have to pay income taxes either:

- Employees or officers of governments other than Canada who are required to reside in Canada, and the members of their families

-

Municipal authorities

-

Crown Corporations (businesses owned by the federal or provincial governments)

-

Agricultural Organizations

-

Registered Charities

-

Registered Amateur Athletic Organizations

-

Organization of Universities and Colleges in Canada

-

Some Housing Corporations

-

Non-profit Research Corporations

-

Labour Organizations

-

Non-profit Organizations

-

Mutual Insurance Corporations

-

Housing Companies

-

Pension Trusts and Corporations

-

Active military and police personnel receive large income tax exemptions

Stacia Loft argues that, since First Nations’ original territories were much larger than reserves; since reserves were harmful to First Nations; and since they could not make a livelihood on reserve but rather had to leave the reserve to prosper; for these reasons income tax exemption should apply not only on reserve but anywhere Status persons go / have had to go.

The argument in favour of tax exemptions generally

Stacia Loft believes that First Nations should be exempt of all taxes imposed by non-Indigenous governments, whether sales taxes, excise taxes, or income taxes. She gives four reasons: sovereignty; jurisdiction deriving from that sovereignty; title to lands in which to exercise that sovereignty; and the fiduciary obligation of the Crown to protect Indigenous interests.

Regarding sovereignty, the federal government under Justin Trudeau has promised a Nation-to-Nation relationship with First Nations; clearly, one Nation does not tax another Nation. Regarding jurisdiction, a sovereign nation should decide on its own tax scheme.

Regarding title, that is, the original ownership of lands, and the way this title was disrespected and violated by settlers and their governments, the amount of compensation owed to First Nations for the last two hundred years, compounded by interest, must by far exceed the amount of income taxes that could be collected.

Meanwhile, Treaties pertaining to the limited amount of land that is reserve land have typically assumed zero taxation of First Nations.

For example:

- The first Euro-Indigenous Treaty, the Two-Row Wampum (1664), famously depicts two Nations moving independently in all respects. This Treaty was extended by the British as the Covenant Chain Treaty (1744). The Treaty of Niagara (1764) was negotiated independently with 25 First Nations in the same spirit.

- The Royal Proclamation of 1763 set forth that trade between Indigenous and non-Indigenous should be free and open, aside from any regulations made, such as the prohibition on purchasing land from First Nations.

- Treaty 3.5 of 1793 specified that Kanien’kehá:ka settlers could enjoy “undisturbed possession and enjoyment” of their territories in Brantford and Tyendinaga, and would be free of rents, fines, and services.

The United Province of Canada passed an 1850 Declaration guaranteeing general tax exemption for Status persons living on reserves or traditional territories not ceded to the Crown.

The tone of historic treaties suggest that exemptions were intended not just for income tax but for on-reserve sales tax, excise taxes on goods produced on reserve, and import tariffs as well.

Flanagan (2019) suggests that the income-tax-free status of reserves can assist them in promoting business development, much like tax-fee enterprise zones in China and other countries.

The argument opposed to tax exemptions

On the other hand, if it can be shown that tax revenues are being collected in order to purchase public goods which benefit First Nations, an argument could be made for them. The absence of federal income tax collection on reserve likely reduces the federal government’s sense of responsibility to provide public goods to reserve communities.

Taxes are unpopular with voters everywhere, and Bands face an uphill battle trying to convince members to vote for Councillors who want to impose taxes. Taxes collected by the Band on reserve, however, would provide Bands with fairly predicable revenue which could be used not only for projects but also as collateral for loans.

Some redistribution from wealthy to poor members does occur naturally on reserves from the strong kinship and community ties. Local taxes could perhaps do more to reduce income inequality on reserve.

Tax exemptions restricted to people living on reserve keep people living on reserve, for better or for worse. Tax exemptions restricted to unincorporated businesses or small corporations provide a disincentive to incorporation and business expansion.

Tax exemptions off-reserve create two classes of taxpayers; this may cause confusion, cheating, and resentment.

In our next chapter, we’ll take a look at Casinos and Cannabis, two industries that some First Nations have been involved in both legally and illegally (from the point of view of contemporaneous Canadian law).

- Wolf Collar (2020), p. 33 ↵

- The net reproductive rate is the number of surviving children per female and it corresponds to the overall rate of births minus deaths for a population. ↵

- Author's calculations. Initial fractions of Canadian population assumed to be fully Status, partly Status and non-Status are, respectively, 97 %, 2.2%, and 0.8%, corresponding to single identity First Nations with Status, single identity First Nations without Status, and all other Canadians in the 2021 Census. ↵

- "Ottawa aware of issues with lengthy process to apply for Indian Status," Globe and Mail March 7, 2023. ↵

- Parliamentary Budget Office (2017) ↵

- Parliamentary Budget Office (2017) ↵

- Parliamentary Budget Office (2017) ↵

- Assembly of First Nations (AFN) (2020) ↵

- Crown Representative (1964) ↵

- According to Loft (2019), these concerns were expressed at the 2018 Annual General Meeting of the AIAI (Association of Iroquois and Allied Nations) ↵

A legal process to replace Indian Status with Canadian citizenship. Could be entered into voluntarily, or imposed on a person.

A fiduciary duty is the legal obligation to act in the best interest of someone over whose affairs you have control. From the Latin word fides, meaning faith or trust.